Carroll, Lewis

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:LewisCarrollSelfPhoto.jpg|thumb|right|Charles Lutwidge Dodgson ( | + | {{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | '''Charles Lutwidge Dodgson''' (January 27 1832 – January 14 1898), better known by the pen name '''Lewis Carroll''' | + | {{epname|Carroll, Lewis}} |

| + | [[category:fix cite refs]] | ||

| + | |||

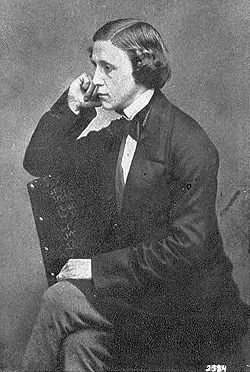

| + | [[Image:LewisCarrollSelfPhoto.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll)--believed to be a self-portrait]] | ||

| + | '''Charles Lutwidge Dodgson''' (January 27, 1832 – January 14, 1898), better known by the pen name '''Lewis Carroll,''' was an English author, [[mathematics|mathematician]], [[logic|logician]], [[clergyman]], and [[photography|photographer]] who is best remembered today as one of the world's most beloved authors of children's stories and nonsense poetry. Carroll's genius for surreal storytelling, wordplay, and pure humor has made him one of the most enduring and critically acclaimed of all writers in the genre. His most famous works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,'' and its sequel ''Through the Looking-Glass,'' as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky." | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Carroll's facility at word play, [[logic]], and [[fantasy]] has delighted audiences ranging from children to the literary elite. But beyond this, his work has become embedded deeply in modern culture, and he has influenced a wide range of artists, from other children's writers to literary giants such as [[Jorge Luis Borges]] and [[James Joyce]]. | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

===Antecedents=== | ===Antecedents=== | ||

| − | Dodgson's family was predominantly northern [[England|English]], with some [[Ireland|Irish]] connections. Conservative and [[High Church]] [[Anglicanism|Anglican]], most of Dodgson's ancestors were | + | Dodgson's family was predominantly northern [[England|English]], with some [[Ireland|Irish]] connections. Conservative and [[High Church]] [[Anglicanism|Anglican]], most of Dodgson's ancestors were British Army officers or [[Church of England]] clergymen. His great-grandfather, also Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become a [[bishop]]; his grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies. |

| − | The elder of these sons — yet another Charles — was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family business and took | + | The elder of these sons—yet another Charles—was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family business and took holy orders. He went to Rugby School, and from there to [[Christ Church, Oxford]]. He was [[mathematics|mathematically]] gifted and won a double first degree which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827, and retired into obscurity as a country [[parson]]. |

===Young Charles=== | ===Young Charles=== | ||

| − | Young Charles Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Warrington, Cheshire, the oldest boy | + | Young Charles Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Warrington, Cheshire, the oldest boy and already the third child of the four-and-a-half year old marriage. Eight more were to follow and, remarkably for the time, all of them—seven girls and four boys —survived into adulthood. When Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in north Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious Rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years. |

| − | In his early years, young Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family testify to a precocious intellect: | + | In his early years, young Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family testify to a precocious intellect: At the age of seven the child was reading ''The Pilgrim's Progress.'' He also suffered from a stammer—a condition shared by his siblings—that often influenced his social life throughout his years. At twelve he was sent away to a small private school at nearby Richmond, where he appears to have been happy and settled. But in 1845, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently greatly depressed. |

===Oxford=== | ===Oxford=== | ||

| − | He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and, after an interval which remains unexplained, went on in January 1851 to [[University of Oxford|Oxford]], attending his father's old college, Christ Church. He had only been at Oxford two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" — perhaps meningitis or a stroke — at the age of forty-seven. | + | He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and, after an interval which remains unexplained, went on in January 1851 to [[University of Oxford|Oxford]], attending his father's old college, Christ Church. He had only been at Oxford two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain"—perhaps meningitis or a stroke—at the age of forty-seven. |

| − | His early academic career veered between high-octane promise and irresistible distraction. He may not always have worked hard, but he was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852 he received a first in Honour Moderations, and shortly after he was nominated to a Studentship | + | His early academic career veered between high-octane promise and irresistible distraction. He may not always have worked hard, but he was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he received a first in Honour Moderations, and shortly after he was nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend Canon Edward Pusey. However, a little later he failed an important scholarship through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship, which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. The income was good, but the work bored him. Many of his pupils were older and richer than he was, and almost all of them were uninterested. However, despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death. |

===Dodgson the artist=== | ===Dodgson the artist=== | ||

| − | From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, sending them to various magazines | + | From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, ''The Comic Times'' and ''The Train,'' as well as smaller magazines like the ''Whitby Gazette'' and the ''Oxford Critic.'' Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the ''Whitby Gazette'' or the ''Oxonian Advertiser''), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855. |

| − | In 1856 he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. | + | In 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A very predictable little romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in ''The Train'' under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll." |

| − | In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life, and greatly influence his writing career | + | In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life, and greatly influence his writing career over the following years. Dodgson became close friends with the mother, Lorina, and the children, particularly the three sisters: Ina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. Although Dodgson himself later denied his "little heroine" was based on any real child,<ref>Morton N. Cohen, ''The Letters of Lewis Carroll'' (London: Macmillan, 1979).</ref>, he is widely assumed to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. There is an acrostic poem at the end of ''Through the Looking Glass'' which supports this view. Reading downward, taking the first letter of each line, spells out Alice's name in full. The poem has no title in ''Through the Looking Glass'' but is usually referred to by its first line, "A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky." |

Though information is scarce, it does seem clear that his friendship with the family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips to nearby Nuneham or Godstow. | Though information is scarce, it does seem clear that his friendship with the family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips to nearby Nuneham or Godstow. | ||

| − | It was on one such expedition, | + | It was on one such expedition, on July 4, 1862, that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest commercial success. Having told the story to Alice Liddell, she begged him to write it down. Dodgson eventually presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground,'' in November 1864. |

| − | Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. | + | Before this, the family of friend and mentor, George MacDonald, read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles ''Alice Among the Fairies'' and ''Alice's Golden Hour'' were rejected, the work was finally published as ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,'' in 1865. The illustrations this time were by [[John Tenniel|Sir John Tenniel]]; Dodgson evidently realized that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. |

| − | In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles ''Alice Among the Fairies'' and ''Alice's Golden Hour'' were rejected, the work was finally published as ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' in 1865. The illustrations this time were by [[John Tenniel|Sir John Tenniel]]; Dodgson evidently | ||

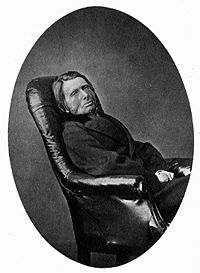

| − | The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego | + | [[Image:Lewis Carroll (1874).jpg|thumb|200px|left|Lewis Carroll, 1874]] |

| + | The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego, Lewis Carroll soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. He also began earning quite substantial sums of money. However, perhaps oddly, he didn't use this income as a means of abandoning his post at Christ Church which he apparently disliked. | ||

| − | In 1872, a sequel — ''Through the Looking-Glass'' — was published. Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that would last some years. | + | In 1872, a sequel—''Through the Looking-Glass''—was published. Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that would last some years. |

| − | In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark a fantastic nonsense poem | + | In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, ''The Hunting of the [[Snark]],'' a fantastic nonsense poem exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of variously inadequate beings, and one beaver, who set off to find the eponymous creature. |

===The later years=== | ===The later years=== | ||

| − | Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, Dodgson's existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, | + | Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, Dodgson's existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, remaining in residence there until his death. His last novel, the two-volume ''Sylvie and Bruno'', was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. Its extraordinary convolutions and apparent confusion baffled most readers, achieving little success. He died at his sisters' home in Guildford on January 14 1898 of pneumonia following influenza. He was not quite sixty-six years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Alice par John Tenniel 32.png|thumb|200px|Alice in Wonderland, illustration by John Tenniel]] | |

| − | |||

'''''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''''' is a work of [[children's literature]] which is generally acclaimed as Dodgson's masterpiece. It tells the story of a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit-hole into Wonderland, a [[fantasy]] realm populated by talking playing cards, anthropomorphic creatures, and other fantastical beings. | '''''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''''' is a work of [[children's literature]] which is generally acclaimed as Dodgson's masterpiece. It tells the story of a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit-hole into Wonderland, a [[fantasy]] realm populated by talking playing cards, anthropomorphic creatures, and other fantastical beings. | ||

| − | The tale is fraught with satirical allusions to Dodgson's friends and to life in the United Kingdom | + | The tale is fraught with satirical allusions to Dodgson's friends and to life in the United Kingdom during the mid nineteenth century in general. The Wonderland described in the story is a place where logic and rules and reality are turned upside-down in ways that have made the story enduringly popular with adults, as well as children. |

| − | The book is often referred to by the abbreviated title '''''Alice in Wonderland''''' | + | The book is often referred to by the abbreviated title '''''Alice in Wonderland.''''' This alternate title was popularized by the numerous film and television adaptations of the story produced over the years. |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | ''Alice'' was first published on 4 | + | ''Alice'' was first published on July 4, 1865, exactly three years after the Dodgson and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed in a boat up the [[Thames River|River Thames]] with three little girls: |

*Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13) ("Prima" in the book's prefatory verse) | *Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13) ("Prima" in the book's prefatory verse) | ||

| Line 56: | Line 65: | ||

*Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8) ("Tertia" in the prefatory verse) | *Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8) ("Tertia" in the prefatory verse) | ||

| − | The journey had started at Folly Bridge near [[Oxford]], | + | The journey had started at Folly Bridge near [[Oxford]], ending five miles away in the village of Godstow. To while away time the Reverend Dodgson told the girls a story that, not so coincidentally, featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure. |

| − | The girls loved the story so much that they asked Dodgson to write it down for them. He eventually did so and on 26 | + | The girls loved the story so much that they asked Dodgson to write it down for them. He eventually did so and on November 26, 1864, he presented Alice with the first manuscript version of the story, which was titled ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground.'' According to Dodgson's diaries, in the spring of 1863, he gave the unfinished manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' to his friend and mentor George MacDonald, whose children loved it. On MacDonald's advice, Dodgson decided to submit ''Alice'' for publication. Before he had even finished the manuscript for Alice Liddell, he was already expanding the 18,000 word original to 35,000 words, most notably adding the episodes about the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea-Party. In 1865, Dodgson's tale was published as ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' by "Lewis Carroll." |

| − | The entire print run sold out quickly. ''Alice'' was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike. Among its first avid readers were young [[Oscar Wilde]] and [[Queen Victoria]]. The book | + | The entire print run sold out quickly. ''Alice'' was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike. Among its first avid readers were the young [[Oscar Wilde]] and [[Queen Victoria]]. The book hasn't been out of print since. ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' has been translated into over 50 languages, including [[Esperanto]] and [[Faroese]]. There have now been over a hundred editions of the book, as well as countless adaptations in other media, especially theater and film. |

==Plot summary== | ==Plot summary== | ||

In the novel, a girl named Alice is bored while on a picnic with her older sister. Everything changes when, idly looking around, she sees a passing white rabbit, dressed in a waistcoat and muttering "Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear!" The rabbit, who seems to be in a dire hurry, quickly scurries by, and Alice, without a second's pause, follows after him down a rabbit-hole. | In the novel, a girl named Alice is bored while on a picnic with her older sister. Everything changes when, idly looking around, she sees a passing white rabbit, dressed in a waistcoat and muttering "Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear!" The rabbit, who seems to be in a dire hurry, quickly scurries by, and Alice, without a second's pause, follows after him down a rabbit-hole. | ||

| − | As soon as she's entered the rabbit-hole, Alice finds herself floating down into a dream world unlike | + | As soon as she's entered the rabbit-hole, Alice finds herself floating down into a dream world unlike anything she could have ever imagined. As she attempts to follow the rabbit, she has myriad adventures: She grows to gigantic size and later shrinks to a the size of a miniature; she meets a group of small animals stranded in a sea of tears; she gets trapped in the rabbit's house when her body spontaneously enlarges again; she meets a baby which changes into a pig, and a cat which disappears leaving only his smile behind; she goes to a never-ending tea party run by a lunatic in a hat; she goes to the shore and meets a [[Griffin|Gryphon]] and a wisecracking turtle; and finally, she attends the trial of the Knave of Hearts, who has been accused of stealing tarts. After all of these fantastic adventures, Alice reaches the end of Wonderland and wakes up, back with her sister. |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 80: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Bowman, Isa | + | * Bowman, Isa. 1899. ''The Story of Lewis Carroll, Told by the Real Alice in Wonderland.'' London: Dent. ISBN 0-8128-2870-4 |

| − | * Cohen, Morton N. | + | * Cohen, Morton N. 1995. ''Lewis Carroll: A Biography.'' London: Macmillan. ISBN 0679745629 |

| − | * Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson | + | * Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. 1898. ''The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll.'' London: T. Fisher Unwin. ISBN 1417926252 |

| − | * Huxley, Francis | + | * Huxley, Francis. 1976. ''The Raven and the Writing Desk.'' ISBN 0-06-012113-0 |

| − | * Kelly, Richard | + | * Kelly, Richard. 1990. ''Lewis Carroll.'' Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 155111223X |

| − | * Leach, Karoline | + | * Leach, Karoline. 1999. ''In the Shadow of the Dreamchild: A New Understanding of Lewis Carroll.'' London: Peter Owen. ISBN 0720610443 |

| − | * Lennon, Florence Becker | + | * Lennon, Florence Becker. 1947. ''Lewis Carroll.'' London: Cassell. ISBN 048622838X |

| − | * Reed, Langford | + | * Reed, Langford. 1932. ''The Life of Lewis Carroll.'' London: W. and G. Foyle. ISBN 0848222512 |

| − | * Taylor, Alexander L., Knight | + | * Taylor, Alexander L., Knight. 1952. ''The White Knight.'' Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. ISBN 0849227003 |

| − | * Taylor, Roger | + | * Taylor, Roger and Edward Wakeling. 2002. ''Lewis Carroll, Photographer.'' ISBN 0691074437 |

| − | * Wullschläger, Jackie | + | * Wullschläger, Jackie. ''Inventing Wonderland.'' ISBN 0-7432-2892-8 |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved October 25, 2022. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.alice-in-wonderland.net/alice1e.html About Alice Liddell]. | |

| − | [http://www.alice-in-wonderland.net/alice1e.html] | + | *[http://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poet.html?id=81205 Poems by Lewis Carroll at PoetryFoundation.org]. |

| − | *[http://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poet.html?id=81205 Poems by Lewis Carroll at PoetryFoundation.org] | + | *[http://lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk/ The Lewis Carroll Society]. |

| − | *[http://lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk/ The Lewis Carroll Society] | + | *[http://www.lewiscarroll.org/ Lewis Carroll Society of North America]. |

| − | *[http://www.lewiscarroll.org/ Lewis Carroll Society of North America] | + | *[http://www.cut-the-knot.org/LewisCarroll/index.shtml Lewis Carroll's Logic Game]. |

| − | + | *[http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/carroll/index.html Lewis Carroll at victorianweb.org]. | |

| − | *[http://www.cut-the-knot.org/LewisCarroll/index.shtml Lewis Carroll's Logic Game] | ||

| − | *[http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/carroll/ | ||

*[http://contrariwise.wild-reality.net Contrariwise; the Association for New Lewis Carroll Studies] | *[http://contrariwise.wild-reality.net Contrariwise; the Association for New Lewis Carroll Studies] | ||

| − | + | *{{gutenberg author | id=Lewis_Carroll | name=Lewis Carroll}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *{{gutenberg author | id=Lewis_Carroll | name=Lewis Carroll}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] |

{{credit2|Lewis_Caroll|106249173|Alice's_Adventures_in_Wonderland|107597920}} | {{credit2|Lewis_Caroll|106249173|Alice's_Adventures_in_Wonderland|107597920}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:19, 25 October 2022

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (January 27, 1832 – January 14, 1898), better known by the pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, clergyman, and photographer who is best remembered today as one of the world's most beloved authors of children's stories and nonsense poetry. Carroll's genius for surreal storytelling, wordplay, and pure humor has made him one of the most enduring and critically acclaimed of all writers in the genre. His most famous works are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky."

Carroll's facility at word play, logic, and fantasy has delighted audiences ranging from children to the literary elite. But beyond this, his work has become embedded deeply in modern culture, and he has influenced a wide range of artists, from other children's writers to literary giants such as Jorge Luis Borges and James Joyce.

Life

Antecedents

Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with some Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were British Army officers or Church of England clergymen. His great-grandfather, also Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become a bishop; his grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies.

The elder of these sons—yet another Charles—was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family business and took holy orders. He went to Rugby School, and from there to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827, and retired into obscurity as a country parson.

Young Charles

Young Charles Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Warrington, Cheshire, the oldest boy and already the third child of the four-and-a-half year old marriage. Eight more were to follow and, remarkably for the time, all of them—seven girls and four boys —survived into adulthood. When Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in north Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious Rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years.

In his early years, young Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family testify to a precocious intellect: At the age of seven the child was reading The Pilgrim's Progress. He also suffered from a stammer—a condition shared by his siblings—that often influenced his social life throughout his years. At twelve he was sent away to a small private school at nearby Richmond, where he appears to have been happy and settled. But in 1845, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently greatly depressed.

Oxford

He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and, after an interval which remains unexplained, went on in January 1851 to Oxford, attending his father's old college, Christ Church. He had only been at Oxford two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain"—perhaps meningitis or a stroke—at the age of forty-seven.

His early academic career veered between high-octane promise and irresistible distraction. He may not always have worked hard, but he was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he received a first in Honour Moderations, and shortly after he was nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend Canon Edward Pusey. However, a little later he failed an important scholarship through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship, which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. The income was good, but the work bored him. Many of his pupils were older and richer than he was, and almost all of them were uninterested. However, despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death.

Dodgson the artist

From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines like the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855.

In 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A very predictable little romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll."

In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life, and greatly influence his writing career over the following years. Dodgson became close friends with the mother, Lorina, and the children, particularly the three sisters: Ina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. Although Dodgson himself later denied his "little heroine" was based on any real child,[1], he is widely assumed to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. There is an acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking Glass which supports this view. Reading downward, taking the first letter of each line, spells out Alice's name in full. The poem has no title in Through the Looking Glass but is usually referred to by its first line, "A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky."

Though information is scarce, it does seem clear that his friendship with the family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips to nearby Nuneham or Godstow.

It was on one such expedition, on July 4, 1862, that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest commercial success. Having told the story to Alice Liddell, she begged him to write it down. Dodgson eventually presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground, in November 1864.

Before this, the family of friend and mentor, George MacDonald, read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour were rejected, the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, in 1865. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently realized that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist.

The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego, Lewis Carroll soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. He also began earning quite substantial sums of money. However, perhaps oddly, he didn't use this income as a means of abandoning his post at Christ Church which he apparently disliked.

In 1872, a sequel—Through the Looking-Glass—was published. Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that would last some years.

In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastic nonsense poem exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of variously inadequate beings, and one beaver, who set off to find the eponymous creature.

The later years

Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, Dodgson's existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, remaining in residence there until his death. His last novel, the two-volume Sylvie and Bruno, was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. Its extraordinary convolutions and apparent confusion baffled most readers, achieving little success. He died at his sisters' home in Guildford on January 14 1898 of pneumonia following influenza. He was not quite sixty-six years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is a work of children's literature which is generally acclaimed as Dodgson's masterpiece. It tells the story of a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit-hole into Wonderland, a fantasy realm populated by talking playing cards, anthropomorphic creatures, and other fantastical beings.

The tale is fraught with satirical allusions to Dodgson's friends and to life in the United Kingdom during the mid nineteenth century in general. The Wonderland described in the story is a place where logic and rules and reality are turned upside-down in ways that have made the story enduringly popular with adults, as well as children.

The book is often referred to by the abbreviated title Alice in Wonderland. This alternate title was popularized by the numerous film and television adaptations of the story produced over the years.

History

Alice was first published on July 4, 1865, exactly three years after the Dodgson and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed in a boat up the River Thames with three little girls:

- Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13) ("Prima" in the book's prefatory verse)

- Alice Pleasance Liddell (aged 10) ("Secunda" in the prefatory verse)

- Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8) ("Tertia" in the prefatory verse)

The journey had started at Folly Bridge near Oxford, ending five miles away in the village of Godstow. To while away time the Reverend Dodgson told the girls a story that, not so coincidentally, featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure.

The girls loved the story so much that they asked Dodgson to write it down for them. He eventually did so and on November 26, 1864, he presented Alice with the first manuscript version of the story, which was titled Alice's Adventures Under Ground. According to Dodgson's diaries, in the spring of 1863, he gave the unfinished manuscript of Alice's Adventures Under Ground to his friend and mentor George MacDonald, whose children loved it. On MacDonald's advice, Dodgson decided to submit Alice for publication. Before he had even finished the manuscript for Alice Liddell, he was already expanding the 18,000 word original to 35,000 words, most notably adding the episodes about the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea-Party. In 1865, Dodgson's tale was published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by "Lewis Carroll."

The entire print run sold out quickly. Alice was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike. Among its first avid readers were the young Oscar Wilde and Queen Victoria. The book hasn't been out of print since. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has been translated into over 50 languages, including Esperanto and Faroese. There have now been over a hundred editions of the book, as well as countless adaptations in other media, especially theater and film.

Plot summary

In the novel, a girl named Alice is bored while on a picnic with her older sister. Everything changes when, idly looking around, she sees a passing white rabbit, dressed in a waistcoat and muttering "Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear!" The rabbit, who seems to be in a dire hurry, quickly scurries by, and Alice, without a second's pause, follows after him down a rabbit-hole.

As soon as she's entered the rabbit-hole, Alice finds herself floating down into a dream world unlike anything she could have ever imagined. As she attempts to follow the rabbit, she has myriad adventures: She grows to gigantic size and later shrinks to a the size of a miniature; she meets a group of small animals stranded in a sea of tears; she gets trapped in the rabbit's house when her body spontaneously enlarges again; she meets a baby which changes into a pig, and a cat which disappears leaving only his smile behind; she goes to a never-ending tea party run by a lunatic in a hat; she goes to the shore and meets a Gryphon and a wisecracking turtle; and finally, she attends the trial of the Knave of Hearts, who has been accused of stealing tarts. After all of these fantastic adventures, Alice reaches the end of Wonderland and wakes up, back with her sister.

Notes

- ↑ Morton N. Cohen, The Letters of Lewis Carroll (London: Macmillan, 1979).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bowman, Isa. 1899. The Story of Lewis Carroll, Told by the Real Alice in Wonderland. London: Dent. ISBN 0-8128-2870-4

- Cohen, Morton N. 1995. Lewis Carroll: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0679745629

- Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. 1898. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. London: T. Fisher Unwin. ISBN 1417926252

- Huxley, Francis. 1976. The Raven and the Writing Desk. ISBN 0-06-012113-0

- Kelly, Richard. 1990. Lewis Carroll. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 155111223X

- Leach, Karoline. 1999. In the Shadow of the Dreamchild: A New Understanding of Lewis Carroll. London: Peter Owen. ISBN 0720610443

- Lennon, Florence Becker. 1947. Lewis Carroll. London: Cassell. ISBN 048622838X

- Reed, Langford. 1932. The Life of Lewis Carroll. London: W. and G. Foyle. ISBN 0848222512

- Taylor, Alexander L., Knight. 1952. The White Knight. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. ISBN 0849227003

- Taylor, Roger and Edward Wakeling. 2002. Lewis Carroll, Photographer. ISBN 0691074437

- Wullschläger, Jackie. Inventing Wonderland. ISBN 0-7432-2892-8

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- About Alice Liddell.

- Poems by Lewis Carroll at PoetryFoundation.org.

- The Lewis Carroll Society.

- Lewis Carroll Society of North America.

- Lewis Carroll's Logic Game.

- Lewis Carroll at victorianweb.org.

- Contrariwise; the Association for New Lewis Carroll Studies

- Works by Lewis Carroll. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.