Kwakwaka'wakw

The term Kwakiutl was usually applied to a group of indigenous peoples of northern Vancouver Island, Queen Charlotte Strait and the Johnstone Strait, who are now known as Kwakwaka'wakw, which means Kwak'wala-speaking-peoples. The term, created by anthropologist Franz Boas, was widely used into the 1980's. It comes from one of the Kwakwaka'wakw tribes, the Kwagu'ł, at Fort Rupert, with whom Franz Boas did most of his anthropological work and whose Indian Act band [1] government is the Kwakiutl First Nation. The term was also misapplied to mean all the tribes who spoke Kwak'wala, as well as three other indigenous peoples whose language is a part of the Wakashan linguistical group, but whose language is not Kwak'wala. These peoples, incorrectly known as the Northern Kwakiutl, were the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk.

The Kwakwaka'wakw (also Kwakiutl) are an Indigenous nation, numbering about 5,500, who live in British Columbia on northern Vancouver Island and the mainland. Kwakwaka'wakw translates into "Kwak'wala speaking tribes," describing the collective tribes within their nation. Their language, now spoken by less than 5% of the population (about 250 people), is Kwak'wala. The Kwakwaka'wakw are known for their history, culture and art. In recent years, the Kwakwaka'wakw have been active on the revitalization of their culture and language.

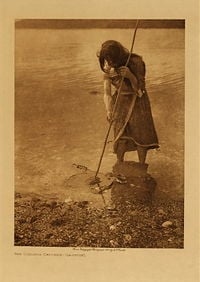

The Kwakwaka'wakw are made up of 17 tribes who all speak the common language of kwak'wala. Their society was highly stratified, with three main classes, determined by heredity: nobles, commoners, and slaves. Their economy was based primarily on fishing, with the men also engaging in some hunting, and the women gathering wild fruits and berries. Ornate weaving and woodwork were important crafts, and wealth, defined by slaves and material goods, was prominently displayed and traded at potlatch ceremonies. These customs were the subject of extensive study by the anthropologist Franz Boas. In contrast to European societies, wealth was not determined by how much you had, but by how much you had to give away. This act of giving away your wealth was one of the main acts in a potlatch.

History

Origins

"The Kwakwaka’wakw creation story is that the ancestor of a ‘na’mima appeared at a specific location by coming down from the sky, out of the sea, or from underground. Generally in the form of an animal, it would take off its animal mask and become a person. The Thunderbird or his brother Kolus, the Gull, the Killer Whale (Orca), a sea monster, a grizzly bear, and a chief ghost would appear in this role. In a few cases, two such beings arrived, and both would become ancestors. There are a few ‘na’mima that do not have the traditional origin, but are said to have come as human beings from distant places. To this group belong the Si’santla’, at one place, their ancestor is called “Son of the Sun” who traveled to as far north as Bella Bella. These ancestors are called “fathers” or “grandfathers,” and the myth is called the “myth at the end of world.”[2]

Colonization

Contact with Europeans

The first documented contact was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. Disease, which developed as a result of direct contact with European settlers along the West Coast of Canada, drastically reduced the Indigenous Kwakwaka'wakw population during the late nineteenth-early twentieth century.

Residential School

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

Cultural revitalization

Restoring their ties to their land, culture, and rights, the Kwakwaka'wakw have undertook much in bringing back their customs, beliefs, and language. Potlatch occur more frequently as families reconnect to their birthright and language programs, classes, and social events utilize the community to restore the language.

Geography

Kwakwaka’wakw population dropped by 75% between 1830-1880.[3]

The Tribes

Kwakwaka'wakw were historically organized into 17 different tribes. Each tribe has its own clans, chiefs, history, culture and peoples, but remain collectively similar to the rest of the kwaka'wala speaking tribes. After the epidemics and colonization, some tribes have become extinct, and others have been merged into communities or First Nations band governments.

| Kwakwaka'wakw tribe | International Phonetics Alphabet | Translation | Village or Community location | Anglicized, archaic variants or adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwagu'ł | Fort Rupert | Kwagyewlth, Kwakiutl | ||

| Mamalilikala | Village Island | |||

| 'Namgis | Those-Who-Are-One-When-They-Come-Together | Alert Bay, Nimpkish River | Nimpkish-Cheslakees | |

| Ławit'sis | Turner Island | Tlowitsis | ||

| A'wa'et'ala | Dzawadli, Knight Inlet | |||

| Da'naxda'xw | New Vancouver, Harbledown Island | Tanakteuk | ||

| Ma'amtagila | Etsekin | |||

| Dzawada'enux | Kingcome Inlet | Tsawataineuk | ||

| Kwikwasut'inux | Gilford Island | |||

| Gwawa'enux | Hope Town | |||

| 'Nak'waxda'xw | Blunden Harbour | Nakoaktok | ||

| Gwa'sala | Smith Inlet | |||

| Gusgimukw | Quatsino | Koskimo | ||

| Gwat'sinux | Winter Harbour | Quatsino | ||

| T'lat'lasikwala | Hope Island | |||

| Weka'yi | Cape Mudge, Quadra Island | Weiwaikai, Yuculta, Euclataws, Laich-kwil-tach, Lekwiltok, Lik<superscript>w</superscript>'ala | ||

| Wiwekam | Campbell River | Weywakum |

Society

Kinship

Kwakwaka'wakw kinship is based on a bilinear structure, with loose characters of a patrilineal culture too. With large extended families and inter connected tribal life. The Kwakwaka'wakw as a whole make up numbers tribes, and within those tribes they were organized into extended families units or na'mima, which means of one kind. Each 'na'mima' had positions that carried responsibilities and privileges. Each tribes had around four 'na'mima', although some had more or less.

All Kwakwaka'wakw follow their genealogy back to their ancestral roots. A head chief, who through primogeniture could trace his origins to that 'na'mima's ancestors, would delineate the roles through out the rest of his family. Every clan had several sub-chiefs, also ranking forth, who gained their title and position through their own families group primogeniture. Organizing to harvest the lands which were part of the property owned by that family, was done by these chiefs.

Kwakwa'wakw society was assembled into four classes, the nobility, attaining through birthright and connection in lineage to ancestors, the aristocracy who attained status through connection to wealth, resources, or spiritual powers which all would be displayed or distributed in the potlatch, the commoner, and the slaves. On the nobility class, "the noble was recognized as the literal conduit between the social and spiritual domains, birth right alone was not enough to secure rank: only individuals displaying the correct moral behavior throughout their life course could maintain ranking status."[4]

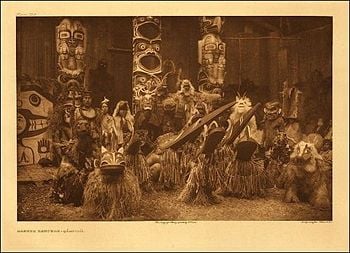

Hamatsa

Hamats is the name of a Kwakwaka'wakw secret society. During the winter months the Kwakwaka'wakw of British Columbia have many ceremonials practiced by different secret societies. The Hamatsa society is the most prestigious of all. It is often called a "cannibal" ritual, and some debate has arisen as to whether the Kwakwaka'wakw do or do not practice ritual cannibalism, whether their "cannibalism" is purely symbolic, or actually literal. Because of the secret nature of the society the answer is not forthcoming.

Central to the Hamatsa ceremonies is the story of some brothers who got lost on a hunting trip and found a strange house with red smoke emanating from its roof. When they visited the house they found its owner gone, but one of the house posts was a living woman with her legs rooted into the floor, and she warned them about the frightful owner of the house, who was named Baxbaxwalanuksiwe, a man-eating giant with four terrible man-eating birds for his companions. In short the men are able to destroy the man-eating giant and gain mystical power and supernatural treasures from him.

In practice the Hamatsa initiate, almost always a young man, is abducted by members of the Hamatsa society and kept in the forest in a secret location where he is instructed in the mysteries of the society. Then at a winter dance festival to which many clans and neighboring tribes are invited the spirit of the man-eating giant is evoked and the initiate is brought in wearing spruce bows and gnashing his teeth and even biting members of the audience. Many dances ensue, as the tale of Baxbaxwalanuksiwe is recounted, and all of the giant man-eating birds dance around the fire.

Finally the society members succeed in taming the new "cannibal" initiate. In the process of the ceremonies what seems to be human flesh is eaten by the initiates. All persons who were bitten during the proceedings are gifted with expensive presents, and many gifts are given to all of the witnesses who are required to recall through their gifts the honors bestowed on the new initiate and recognize his station within the spiritual community of the clan and tribe.

Property

Law

Economy

The Kwakwaka'wakw were a very wealthy people.

Culture

The Kwakwaka'wakw are a highly stratified bilineal culture of the Pacific Northwest. The Kwakwaka'wakw as a whole make up 17 separate tribes, each with their own history, culture and governance. Commonly among the tribes, there would be a tribal chief, who acted as the head chief of the entire tribe, then below him numerous clan or family chiefs. In some of the tribes, there also existed Eagle Chiefs, but this was a separate society within the main society and applied to the potlatching only. The Kwakwaka'wakw are one of the few bilineal cultures. Traditionally the rights of the family would be passed down through the paternal side, but in rare occasions, one could take the maternal side of their family also. Within the pre-colonization times, the Kwakwaka'wakw were made up of three classes; nobles, commoners, and slaves. The Kwakwaka'wakw shared many cultural and political alliances with numerous neighbors in the area including the Nuu-chah-nulth, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv and some Coast Salish. {{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

Language

Kwak'wala (also Kwagiutl or Kwakiutl) is the Indigenous language spoken by the Kwakwaka'wakw. It belongs to the Wakashan language family. There are about 250 Kwak'wala speakers today, which amounts to 5% of the Kwakwaka'wakw population. Because of the small number of speakers, and the fact that very few children learn Kwak'wala as a first language, its long-term viability is in question. However, interest from many Kwakwaka'wakw in preserving their language and a number of revitalization projects are countervailing pressures which may extend the viability of the language.

The ethnonym Kwakwaka'wakw literally means "speakers of Kwak'wala," effectively defining an ethnic connection by reference to a shared language. However, the Kwak'wala spoken by each of the surviving tribes with Kwak'wala speakers exhibits dialectical differences from that spoken by other tribes. There are four major dialects which are unambiguously dialects of Kwak'wala: Kwak̓wala, ’Nak̓wala, G̱uc̓ala and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala.[5]

In addition to these dialects, there are also Kwakwaka'wakw tribes that speak Liq'wala. Liq'wala has sometimes been considered to be a dialect of Kwak'wala, and sometimes a separate language. The standard orthography for Liq'wala is quite different from the most widely-used orthography for Kwak'wala, which tends to widen the apparent differences between Liq'wala and Kwak'wala.

The Kwak'wala language is a part of the Wakashan language group. Word lists and some documentation of Kwak'wala were created from the early period of contact with Europeans in the 18th century, but a systematic attempt to record the language did not occur before the work of Franz Boas in the late 19th and early 20th century.The use of Kwak'wala declined significantly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mainly due to the assimilationist policies of the Canadian government, and above all the mandatory attendance of Kwakwa'wakw children at residential schools. Although Kwak'wala and Kwakwaka'wakw culture have been well-studied by linguists and anthropologists, these efforts did not reverse the trends leading to language loss. According to Guy Buchholtzer, "The anthropological discourse had too often become a long monologue, in which the Kwakwaka'wakw had nothing to say." [6] As a result of these pressures, there are relatively few Kwak'wala speakers today, and most remaining speakers are past the age of child-rearing, which is considered crucial for language transmission. As with many other indigenous languages, there are significant barriers to language revitalization.[7]

However, a number of revitalization efforts have recently attempted to reverse language loss for Kwak'wala. A proposal to build a Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations Centre for Language Culture has gained wide support.[8] A review of revitalization efforts in the 1990s shows that the potential to fully revitalize Kwak'wala still remains, but serious hurdles also exist.[9]

Arts

Visual

In the old times, the art “symbolized the essential consanguinity of all living beings beneath the mask of their particular species.”[10]

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

Music

Kwakwaka'wakw music is the ancient art of the Indigenous or Aboriginal Kwakwaka'wakw peoples.. The music is an ancient art form, stretching back thousands of years. The music is used primarily for ceremony and ritual, and is based around percussive instrumentation, especially , log, box, and hide drums, as well as rattles and whistles. The four-day Klasila festival is an important cultural display of song and dance; it occurs just before the advent of the tsetseka, or winter. {{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

Ceremonies and events

Potlatch

“We want to know whether you have come to stop our dances and feasts, as the missionaries and agents who live among our neighbors try to do. We do not want to have anyone here who will interfere with our customs. We were told that a man-of-war would come if we should continue to do as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers have done. But we do not mind such words. Is this the white man’s land? We are told it is the Queen’s land, but no! It is mine.

Where was the Queen when our God gave this land to my grandfather and told him, “This will be thine?” My father owned the land and was a mighty Chief; now it is mine. And when your man-of-war comes, let him destroy our houses. Do you see yon trees? Do you see yon woods? We shall cut them down and build new houses and live as our fathers did.

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, “Do as the Indian does?” It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.

- - O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis Chief of the Kwagu'ł “Fort Rupert Tribes,” to Franz Boas, October 7, 1886

The potlatch culture of the Northwest is famous and widely-studied and remains alive in Kwakwaka'wakw, as does the lavish artwork for which their people and their neighbours are so renowned. The phenomenon of the potlatch and the vibrant societies and cultures associated with it can be found in Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch , which details the incredible artwork and legendary material that go with the other aspects of the potlatch, and gives a glimpse into the high politics and great wealth and power of the Kwakwaka'wakw chiefs.

The potlatch was also seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agenda's. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was “by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.”[11] Thus in 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practice. The official legislation read, “Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in a jail or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.”

Eventually it became amended to be more inclusive as earlier discharged on technicalities. Legislation was then expanded to include guest who participated in the ceremony. The Kwakwaka'wakw were too large to police, and enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offense from criminal to summary, which meant ‘the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence.”[12]

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, the Kwakwaka'wakw now openly hold potlatch to commit to the restoring of their ancestors ways. Potlatch now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright.

Housing and shelter

Kwakiutl built their houses from cedar-plank. They were very large, up to 100 ft. They could hold about 50 people, usually families from the same clan. In the entrance, there was usually a totem pole with different animals on it.

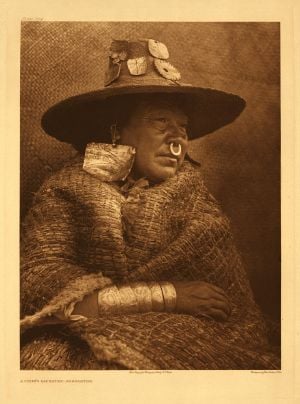

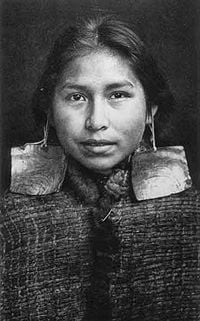

Clothing and regalia

Transportation

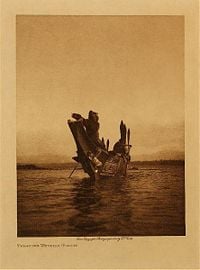

Kwakwaka'wakw transportation was like other coastal peoples. Being an ocean and coastal people, the main way of travel was by canoe. Cedar dug out canoes, made from one cedar log, would carved to be used by individuals, families, and tribes. Sizes varied from ocean-going canoes for long sea-worth travel in trade mission, to smaller local canoes for inter-village travel.

Food and cuisine

The Kwakwaka'wakw lived were excellent hunters, fishers, and gatherers. Living in the costal regions seafood was a staple of their diet supplemented by berries. Salmon was a major catch during spawning season when the salmon would be swimming upriver. In addition, they sometimes went whale harpooning for which a trip could last days while the whale was being stalked.They ate most of the stuff that you can find in the north west coast.

Mythology

Food

The Kwakwaka'wakw lived in the Northwest Coast region and were excellent hunters, fishers, and gatherers. They mainly ate berries for fruit and the major catches for fish was Salmon traveling upriver in the summer. They sometimes went whale harpooning. The trip could last for days while the whale was being stalked. The wealthiest sometimes threw potlatches or giveaways where they would give most of their possessions to the guests as a way to show wealth and power.

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

Notable Kwakwaka'wakw

- David Neel

- James Sewid

- George Hunt (ethnologist)

- Calvin Hunt

- Henry Hunt (artist)

- Richard Hunt (artist)

- Tony Hunt (artist)

- Mungo Martin

- Willie Seaweed

Popular culture

In the Land of the Head Hunters (also called In the Land of the War Canoes) is a 1914 silent documentary film showing the lives of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia.

It was written and directed by Edward S. Curtis. In 1999 the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Notes

- ↑ Thunderbird Park – A Place of Cultural Sharing. Royal British Columbia Museum. Retrieved 2006-06-24. House built by Mungo Martin and David Martin with carpenter Robert J. Wallace. Based on Chief Nakap'ankam's house in Tsaxis (Fort Rupert). The house "bears on its house-posts the hereditary crests of Martin's family." It continues to be used for ceremonies with the permission of Chief Oast'akalagalis 'Walas 'Namugwis (Peter Knox, Martin's grandson) and Mable Knox. Pole carved by Mungo Martin, David Martin and Mildred Hunt. "Rather than display his own crests on the pole, which was customary, Martin chose to include crests representing the A'wa'etlala, Kwagu'l, 'Nak'waxda'xw and 'Namgis Nations. In this way, the pole represents and honours all the Kwakwaka'wakw people."

- ↑ Boas, Contributions to the Ethnology of the Kwakiutl, Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, vol. 3, New York: Columbia University Press, 1925, 229-30.

- ↑ Duff Wilson, The Indian History of British Columbia, 38-40; Sessional Papers, 1873-1880.

- ↑ oseph Masco, “It is a Strict Law that Bids Us Dance”: Cosmologies, Colonialism, Death, and Ritual Authority in the Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch, 1849 to 1922, 48.

- ↑ Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw/Kʷakʷəkəw̓akʷ Communities

- ↑ SFU News Online - Native language centre planned - July 07, 2005

- ↑ Stabilizing Indigenous Languages: Conclusion

- ↑ SFU News Online - Native language centre planned - July 07, 2005

- ↑ http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/%7Ejar/RIL_4.html Reversing Language Shift: Can Kwak'wala Be Revived?

- ↑ Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 67.

- ↑ Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1977, 207.

- ↑ Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 159.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bancroft-Hunt, Norman. 1988. People of the Totem: The Indians of the Pacific Northwest. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Goldman, Irving. The mouth of heaven: An introduction to Kwakiutl religious thought.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. 1991. Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. U. Washington Press.

- McDowell, Jim. Hamatsa: The Enigma of Cannibalism on the Pacific Northwest Coast.

- Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch Aldona Jonaitis (Editor) U. Washington Press 1991 (also a publication of the American Museum of Natural History)

- Bancroft-Hunt, Norman. People of the Totem: The Indians of the Pacific Northwest University of Oklahoma Press, 1988

- Boas, Contributions to the Ethnology of the Kwakiutl, Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, vol. 3, New York: Columbia University Press, 1925.

- Fisher, Robin. Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1977.

- Goldman, Irving. The Mouth of Heaven: an Introduction to Kwakiutl Religious Thought, New York: Joh Wiley and Sons, 1975.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991.

- Masco, Joseph. “It is a Strict Law that Bids Us Dance”: Cosmologies, Colonialism, Death, and Ritual Authority in the Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch, 1849 to 1922, San Diego: University of California.

- Reid, Martine and Daisy Sewid-Smith. Paddling to Where I Stand, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004.

- Spradley, James. Guests Never Leave Hungry, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969.

- Umista Cultural Society. Creation myth of Kwakwaka’wakw (December 1 2007).

- Walens, Stanley “Review of the Mouth of Heaven by Irving Goldman,” American Anthropologist, 1981.

- Wilson, Duff. The Indian History of British Columbia, 38-40; Sessional Papers, 1873-1880.

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.