Difference between revisions of "Intersectionality" - New World Encyclopedia

| (313 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File:Venn's four ellipse construction. | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

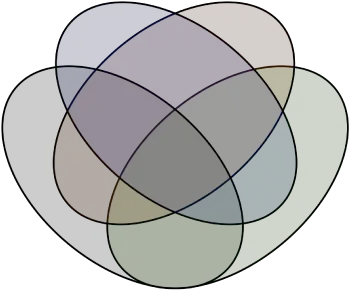

| + | [[File:Venn's four ellipse construction.png|thumb|350px|An intersectional analysis considers all the factors that apply to an individual in combination, rather than considering each factor in isolation.]] | ||

| − | + | '''Intersectionality''' is a theoretical framework for understanding discrimination from multiple sources. It identifies advantages and disadvantages that are felt by people due to a combination of factors. For example, a black woman might face discrimination from a business that is not distinctly due to her [[Race (human categorization)|race]] (because the business does not discriminate against black men) nor distinctly due to her [[gender]] (because the business does not discriminate against white women), but due to a combination of the two factors. | |

| − | ''' | ||

| − | + | The term was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in a 1989 essay. Since that time it has had an impact on both [[feminism]] and the social sciences in general. It is based on the view that race, gender and class are the major determinants of identity, and that minorities from each of these categories are oppressed. Those individuals who are members of more than one of these groups face unique combinations of oppression. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Intersectionality has been critiqued as inherently ambiguous based on its utilization of [[postmodernism|postmodernist]] theories of power and the view that the subjective experience of the person who feels oppressed authenticates the oppression. The ambiguity of this theory means that it can be perceived as unorganized and lacking a clear set of defining goals. As it is based in [[standpoint theory]], critics say the focus on subjective experiences can lead to contradictions and the inability to identify common causes of oppression. | |

| − | |||

| − | Intersectionality | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Definition== | ==Definition== | ||

| − | Intersectionality is a | + | The term was introduced in a 1989 essay by Kimberlé Crenshaw, entitled "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics."<ref name=Crenshaw1989>Kimberlé Crenshaw, [https://philpapers.org/archive/CREDTI.pdf "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,"] ''University of Chicago Legal Forum'', 1989. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref> Intersectionality is a qualitative [[analytic framework]] developed in the late 20th century that identifies how interlocking systems of [[Power (social and political)|power]] affect those who are most [[Social exclusion|marginalized in society]]<ref>Brittney Cooper, Mary Hawkesworth, and Lisa Disch, ''The Journal of Intersectionality'' vol. 1, February 1, 2016.</ref> and takes these relationships into account to analyze [[Social equity|social]] and [[Political egalitarianism|political equity]].<ref> [https://iwda.org.au/what-does-intersectional-feminism-actually-mean What Does Intersectional Feminism Actually Mean?,"] ''International Women's Development Agency'', May 11, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref> It is a theoretical framework that is generally applied to the ways that [[Social identity|social and political identities]]<ref>Abigail Tucker, [https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-much-is-being-attractive-worth-80414787/ "How Much is Being Attractive Worth?"] ''Smithsonian Magazine'', November 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref><ref>Kelsey Yonce, [https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/745 "Attractiveness privilege : the unearned advantages of physical attractiveness,"] ''Theses, Dissertations, and Projects, January 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref> [[Height discrimination|height]],<ref>Omer Kimhi, [https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3166828 "Falling Short – the Discrimination of Height Discrimination,"], April 22, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref> etc.) combine to create unique modes of [[discrimination]] and [[Social privilege|privilege]]. Intersectionality expands the lens of the first and second [[waves of feminism]], which largely focused on the experiences of women who were both [[White women|white]] and [[Middle class|middle-class]], to include the different experiences of [[women of color]], women in poverty, immigrants, and other groups. Intersectional feminism aims to separate itself from [[white feminism]] by acknowledging women's different experiences and identities. |

| − | + | Intersectionality critiques analytical systems that treat each oppressive factor in isolation, asserting that discrimination against black women is not a simple sum of the discrimination against black men and the discrimination against white women.<ref>Kimberlé Crenshaw, [https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality "The urgency of intersectionality,"]. Retrieved December 2, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ==Historical Background== |

| + | The ideas behind intersectional feminism existed long before the term was coined. [[Sojourner Truth]]'s 1851 "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, for example, suggests themes found in intersectionality, speaking as a former slave to critique essentialist notions of femininity.<ref>Sojourner Truth, "Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio" (1851) in ''Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric(s)'', Joy Ritchie and Kate Ronald, eds., (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0822957539), 144-146.</ref><ref>Avtar Brah and Ann Phoenix, [http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol5/iss3/8/ "Ain't I A Woman? Revisiting intersectionality,"] ''Journal of International Women's Studies'' 5(3), 2004, 75–86. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref>Similarly, in her 1892 essay, "The Colored Woman's Office", [[Anna J. Cooper|Anna Julia Cooper]] identifies black women as the most important actors in social change movements, because of their experience with multiple facets of oppression.<ref>Anna Julia Cooper, "The colored woman's office" in ''Social theory: the multicultural, global, and classic readings'', 6th edition, Charles Lemert ed., (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0813350448).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The term also has historical and theoretical links to the concept of "simultaneity," which was promoted during the 1970s by members of the [[Combahee River Collective]] in [[Boston, Massachusetts]].<ref>Robyn Wiegman, ''Object lessons'' (Durham, NC; Duke University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0822351603), 244.</ref> | |

| + | Simultaneity refers to the simultaneous influences of race, class, gender, and sexuality, which informed the member's lives and their resistance to oppression.<ref>Amanda Walker Johnson, "Resituating the Crossroads: Theoretical Innovations in Black Feminist," ''Souls'' 19(4), October 2, 2017, 401–415.</ref> The women of the Combahee River Collective advanced an understanding of African-American experiences that challenged analyses emerging from Black and male-centered social movements, as well as those from mainstream cisgender, white, middle-class, heterosexual feminists.<ref>Brian Norman, "'We' in Redux: The Combahee River Collective's ''Black Feminist Statement''," ''Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies'' 18(2), 2007: 104.</ref> | ||

| − | = | + | [[Patricia Hill Collins]] has located the origins of intersectionality among black feminists, [[Chicana feminism|Chicana]] and other Latina feminists, [[indigenous feminists]] and Asian American feminists in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and noted the existence of intellectuals at other times and in other places who discussed similar ideas about the interaction of different forms of inequality, such as [[Stuart Hall (cultural theorist)|Stuart Hall]] and the [[cultural studies]] movement, [[Nira Yuval-Davis]], Anna Julia Cooper and [[Ida B. Wells]]. She noted that as [[second-wave feminism]] receded in the 1980s, feminists of color such as [[Audre Lorde]], [[Gloria E. Anzaldúa]] and [[Angela Davis]] entered academic environments and brought their perspectives to their scholarship. During this decade many of the ideas that would together be labeled as "intersectionality" coalesced in U.S. academia under the banner of "race, class and gender studies."<ref name=Collins2015>Patricia Hill Collins, "Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas," ''Annual Review of Sociology'' 41 (2015): 1–20.</ref> |

| − | + | [[W. E. B. Du Bois]] theorized that the intersectional paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain certain aspects of the black political economy. Sociologist Patrcia Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."<ref name=Collins2000>Patricia Hill Collins, "Gender, black feminism, and black political economy," ''Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science'' 568(1) (March 2000): 41–53.</ref> Du Bois omitted gender from his theory and considered it more of a personal identity category. | |

| − | + | In 1981 [[Cherríe Moraga]] and [[Gloria E. Anzaldúa|Gloria Anzaldúa]] published the first edition of ''[[This Bridge Called My Back]]''. This anthology explored how classifications of sexual orientation and class also mix with those of race and gender to create even more distinct political categories. Many black, Latina, and Asian writers featured in the collection stress how their sexuality interacts with their race and gender to inform their perspectives. Similarly, poor women of color detail how their socio-economic status adds a layer of nuance to their identities, ignored or misunderstood by middle-class white feminists.<ref>Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (eds.), ''This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color'' 4th ed. (Albany, NY: State University of New York (SUNY) Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1438454382).</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Intersectionality and Feminism=== | |

| + | The concept of intersectionality addressed dynamics that were previously overlooked by feminist theory and movements.<ref>Becky Thompson, "Multiracial feminism: recasting the chronology of Second Wave Feminism," ''Feminist Studies'' 28(2) (Summer 2002): 337–360.</ref> Racial inequality was a factor that was largely ignored by first-wave feminism, which was primarily concerned with gaining political equality between white men and white women. Early women's rights movements often exclusively pertained to the membership, concerns, and struggles of white women.<ref> Julia T. Wood and Natalie Fixmer-Oraiz, ''Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture'' (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2015, ISBN 978-1305280274), 59–60.</ref> Second-wave feminism stemmed from [[Betty Friedan]]’s ''[[The Feminine Mystique]]'' and worked to dismantle sexism relating to the perceived domestic purpose of women. While feminists during this time achieved success through the [[Equal Pay Act of 1963]], [[Title IX]], and ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'', they largely alienated black women from platforms in the mainstream movement.<ref>Constance Grady, [https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth "The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained,"] ''Vox'', July 20, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.</ref> However, third-wave feminism—which emerged shortly after the term "intersectionality" was coined in the late 1980s—noted the lack of attention to race, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity in early feminist movements, and tried to provide a channel to address political and social disparities.<ref> Wood and Fixmer-Oraiz, 72–73.</ref> | ||

| − | + | According to black feminists and many white feminists, experiences of class, gender, and sexuality cannot be adequately understood unless the influence of racialization is carefully considered. This focus on racialization was highlighted many times by scholar and feminist [[bell hooks]], specifically in her 1981 book ''Ain't I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism''.<ref>bell hooks, ''Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism'' (London, England and Boston, MA: Pluto Press South End Press, 1981, ISBN 978-1138821514).</ref> Feminists argue that an understanding of intersectionality is a vital element of gaining political and social equality and improving our democratic system.<ref>Maria D'Agostino and Helisse Levine, ''Women in Public Administration: Theory and practice'' (Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011, ISBN 0763777250), 8.</ref> Collins's theory represents the sociological crossroads between [[second-wave feminism|modern]] and [[Post-modern feminism|post-modern feminist thought]].<ref name=Collins2000/> | |

| − | + | Author [[bell hooks]], <!-- no, that's how she styles herself like e e cummings —> argued that the emergence of intersectionality "challenged the notion that 'gender' was the primary factor determining a woman's fate."<ref name=bellhooks>bell hooks, ''Feminist Theory: from margin to center'' 3rd. ed., (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 978-1138821668).</ref> The historical exclusion of black women from the feminist movement in the United States resulted in many black 19th and 20th century feminists, such as [[Anna J. Cooper|Anna Julia Cooper]], challenging their historical exclusion. They disputed the ideas of earlier feminist movements, which were primarily led by white middle-class women, suggesting that women were a homogeneous category who shared the same life experiences.<ref>Angela Davis, ''Women, Race & Class'' (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1983, ISBN 978-0394713519).</ref> The forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women were different from those experienced by black, poor, or disabled women. Feminists could then begin seeking ways to understand how gender, race, and class combine to "determine the female destiny."<ref name=bellhooks/> | |

| − | Author [[bell hooks]], <!-- no, that's how she styles herself like e e cummings —> argued that the emergence of intersectionality "challenged the notion that 'gender' was the primary factor determining a woman's fate."<ref name= | ||

| − | == | + | ==Introduction of the idea== |

| − | + | ===Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw=== | |

| − | The term | + | The term was coined by [[black feminist]] scholar [[Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw]] in 1989. Crenshaw introduced the theory of intersectionality in her 1989 paper written for the [[University of Chicago Legal Forum]], "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics."<ref name=Crenshaw1989/><ref>[https://www.law.columbia.edu/pt-br/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality "Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later,"] Columbia Law School, June 8, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2020.</ref> The main argument is that the experience of [[Black people|black]] women cannot be understood by examining black experience or a woman's experience independently. It must include the interactions between the two, which frequently reinforce each other.<ref>Sheila Thomas and Kimberlé Crenshaw, "Intersectionality: the double bind of race and gender," ''Perspectives Magazine'', American Bar Association, Spring 2004, 2.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | In order to show that non-white women have a vastly different experience from white women due to their race and/or class and that their experiences are not easily voiced or amplified, Crenshaw explores two types of male violence against women: [[domestic violence]] and [[rape]]. Through her analysis of these two forms of male violence against women, Crenshaw says that the experiences of non-white women consist of a combination of both racism and sexism. The argument is that because non-white women are present within discourses that have been designed to address either race or sex separately, non-white women are marginalized within both of these systems of oppression.<ref name=Crenshaw1991>Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, "Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color," ''Stanford Law Review'' 43(6) (July 1991): 1241–1299.</ref> | |

| − | + | In her work, Crenshaw identifies three aspects of intersectionality that affect the visibility of non-white women: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence and rape in a manner qualitatively different than that of white women. Political intersectionality examines how laws and policies intended to increase equality have paradoxically decreased the visibility of violence against non-white women. Finally, representational intersectionality delves into how [[Popular culture|pop culture]] portrayals of non-white women can obscure their own authentic lived experiences. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The theory began as an explanation of the oppression of women of color within society. The analysis has expanded to include many more aspects of social identity. Identities most commonly referenced in the [[Fourth-wave feminism|fourth wave of feminism]] include race, gender, sex, sexuality, class, ability, nationality, citizenship, religion and body type. The term Intersectionality was not adopted widely by feminists until the 2000s. |

| − | Collins | + | ===Patricia Hill Collins=== |

| + | Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins refers to the various intersections of social inequality as the [[matrix of domination]]. These are also known as "vectors of oppression and privilege."<ref>George Ritzer and Jeffrey Stepnisky, ''Contemporary Sociological Theory and its Classical Roots: The basics'' (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2013, ISBN 978-0078026782), 204.</ref> She developed the concept primarily to apply to the experience of African-American women. Intersectionality, Collins says, replaced her own previous coinage "black feminist thought," and "increased the general applicability of her theory from African American women to all women."<ref>Susan A. Mann and Douglas J. Huffman, "The decentering of second wave feminism and the rise of the third wave," ''Science & Society'' 69(1) (January 2005), 61.</ref> Much like Crenshaw, Collins argues that cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society, such as race, gender, class, and ethnicity.<ref name=Collins2000/> Collins describes this as "interlocking social institutions [that] have relied on multiple forms of segregation... to produce unjust results".<ref>Patricia Hill Collins, ''Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment'' 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009, ISBN 978-0415924832), 277.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Collins sought to create frameworks to think about intersectionality, rather than expanding on the theory itself. She identified three main branches of study within intersectionality. One branch deals with the background, ideas, issues, conflicts, and debates within intersectionality. Another branch seeks to apply intersectionality as an analytical strategy to various [[social institutions]] in order to examine how they might perpetuate social inequality. The final branch formulates intersectionality as a critical praxis to determine how [[social justice]] initiatives can use intersectionality to bring about social change.<ref name=Collins2015/> | |

| − | + | Speaking from a [[critical theory|critical]] standpoint, Collins points out that Brittan and Maynard say that "domination always involves the [[objectification]] of the dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity of the oppressed."<ref name=Collins1986>Patricia Hill Collins, "Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought," ''Social Problems'' 33(6) (October 1986): S14–S32.</ref> She later notes that self-valuation and self-definition are two ways of resisting oppression. Practicing [[self-awareness]] helps to preserve the self-esteem of the group that is being oppressed and allows them to avoid any dehumanizing outside influences. | |

| − | + | ==Intersectionality and Postmodernism== | |

| + | Crenshaw, Collins, and other theorists who have shaped intersectionality rely on a postmodern view of race and gender as [[social constructionism|socially constructed]]. Their theories adopted the postmodern view of power structures advocated by [[Michel Foucault]] and his followers. Foucault argued that power structures favored privileged groups within society. He critiqued the idea that power could be neutral, or that their was a common heritage to which we could all ascribe and aspire. Different groups all have a different experience of the power structure. Their experience is [[Social constructionism|socially-constructed]] by that experience. But while Foucault and other promoters of postmodernism tended to focus on the limits of power, Crenshaw argues that these socially-constructed identities should be seen as the location of political empowerment and community building. There are several intertwined postmodern theories on which intersectionality is built. | ||

| − | + | ===Intersectionality and Critical Race Theory=== | |

| + | Intersectionality has a number of antecedents. Key among them is Critical Race Theory. Critical Race Theory developed within legal studies starting in the 1970s. It was pioneered by Law Professor Derek Bell at Harvard, whose students included Kimberlé Crenshaw. Critical Race Theory began by focusing on issues of discrimination and addressing poverty. Bell, Richard Delgado, and other legal scholars had a more materialist focus. However, in the intervening period between the 1970s and the 1990s, [[postmodernism]] became more popular within academia. Crenshaw and other scholars influenced by postmodernism shifted the focus of Critical Race Theory from a more Marxist basis, to one based on postmodernism and questions of identity. | ||

| − | + | On identity, Crenshaw distinguishes the difference between the older, civil rights approach and one based on a new one rooted in [[identity politics]]: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| + | We can call recognize the distinction between the claim, "I am Black" and the claim "I am a person who happens to be Black." "I am Black" takes the socially imposed identity and empowers it as an anchor of subjectivity. "I am Black" becomes not simply a statement of resistance but also a positive discourse of self-identification, intimately linked to celebratory statement like the Black nationalist "Black is beautiful."<ref name=Crenshaw1991/> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Crenshaw explicitly rejects the statement "I am a person who happens to be Black," which had been the formulation of the liberal inclusion agenda in favor of embracing the socially constructed racial category as a self-identification. | |

| − | == | + | ===Intersectionality and Identity politics=== |

| − | == | + | The focus on self-identification based on socially-constructed identities is an explicit rejection of the earlier liberal civil rights model. Civil rights is grounded in the liberal view of equality of opportunity. The goal of civil rights had been removing barriers that prevented racial minorities from equal access, such as voting rights, integration of schools, [[affirmative action]], and other policies designed to give minorities the same opportunities. In its place, intersectionality explicitly embraces [[identity politics]]. For Crenshaw, "identity-based politics has been a source of strength, community and intellectual development."<ref name=Crenshaw1991/> |

| − | |||

| − | + | Marginalized groups often gain a status of being an "other." In essence, you are "an other" if you are different from what [[Audre Lorde]] calls the [[Normality (behavior)|mythical norm]]. [[Gloria Anzaldúa]] theorizes that the sociological term for this is "[[othering]]," or specifically attempting to establish a person as unacceptable based on a certain criterion that fails to be met.<ref>Ritzer and Stepnisky, 205.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | === Standpoint Theory === | |

| + | Based on the postmodern rejection of [[Enlightenment]] concepts of truth and power, intersectionality accepts that the socially constructed position gives each group in society a different standpoint. [[Standpoint theory]] claims that one's experience of either dominance or oppression depends on one's standpoint within the hierarchy of power. Based on that standpoint, it also argues that those who are in oppressed groups can see the power relations in a way that the dominant groups cannot. People in a position of power are said to be privileged. Further, they do not know their own privilege. Those are are said to be oppressed know not only their own standpoint, but the privilege of those in positions of power. | ||

| − | + | Patricia Hill Collins argues that standpoint epistemology and [[identity politics]] are the two tools for those who are marginalized to speak their truth. Standpoint theory gives them the epistemic authority and identity politics the platform on which to state it.<ref>Patricia Hill Collins, "Intersectionality and Epistemic Injustice," in ''The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice'', Ian James Kidd, Jose Medina, and Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr. (eds.), (London, England: Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0367370633), 119.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Both Collins and [[Dorothy E. Smith|Dorothy Smith]] have been instrumental in providing a sociological definition of [[standpoint theory]]. Individuals who share an identity status are said to have a common experience which shapes a common perspective. Knowledge is subjective and unique to each socially-constructed identity group; it varies depending on the social conditions under which it was produced.<ref>Susan A. Mann, Lori R. Kelley, "Standing at the crossroads of modernist thought: Collins, Smith, and the new feminist epistemologies," ''Gender & Society'' 11(4) (August 1997): 392.</ref> | |

| − | + | Collins argues that these socially-constructed identities means that even successful minorities remain the other in society. For example, a Black woman, may become influential in a particular field, she may feel as though she does not belong. Their personalities, behavior, and cultural being overshadow their value as an individual; thus, they become the outsider within.<ref name=Collins1986/> As people move from a common cultural world (i.e., family) to that of modern society.<ref>Ritzer and Stepniski, 207. </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Intersectionality in a global context== | |

| − | + | Over the last couple of decades in the [[European Union]] (EU), there has been discussion regarding the intersections of social classifications. Before Crenshaw coined her definition of intersectionality, there was a debate on what these societal categories were. The categorization between gender, race, and class has turned into a multidimensional intersection of "race" including religion, sexuality, ethnicities, etc. In the EU and UK, they refer to these intersections under the notion of multiple discrimination. The EU passed a non-discrimination law which addresses these multiple intersections; however, there is debate on whether the law is still proactively focusing on the proper inequalities.<ref>Dagmar Schiek and Anna Lawson (eds.), ''European Union Non-Discrimination Law and Intersectionality: Investigating the Triangle of Racial, Gender and Disability Discrimination'' (Abingdon, UK: Routledge Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0754679806).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | Over the last couple of decades in the [[European Union]] (EU), there has been discussion regarding the intersections of social classifications. Before Crenshaw coined her definition of intersectionality, there was a debate on what these societal categories were. | ||

| − | + | Outside of the EU, intersectional categories have also been considered. In ''Analysing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts'', the authors argue: "The impact of patriarchy and traditional assumptions about gender and families are evident in the lives of Chinese migrant workers (Chow, Tong), sex workers and their clients in South Korea (Shin), and Indian widows (Chauhan), but also Ukrainian migrants (Amelina) and Australian men of the new global middle class (Connell)." This text argues for many more intersections of discrimination for people around the globe than Crenshaw originally accounted for in her definition.<ref>Esther Ngan-ling Chow, Marcia Texler Segal, and Tan Lin (eds.), ''Analysing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts'' (Bingley, England: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2011, ISBN 978-0857247438).</ref> | |

| − | + | Chandra Mohanty discusses alliances between women throughout the world as intersectionality in a global context. She rejects the western feminist theory, especially when it writes about global women of color and generally associated "third world women." She argues that "third world women" are often thought of as a homogenous entity, when, in fact, their experience of oppression is informed by their geography, history, and culture. When western feminists write about women in the global South in this way, they dismiss the inherent intersecting identities that are present in the dynamic of feminism in the global South. Mohanty questions the performance of intersectionality and relationality of power structures within the US and colonialism and how to work across identities with this history of colonial power structures.<ref>Chandra Mohanty, "Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses," ''Boundary 2'' 12(3) (Spring-Autumn 1984): 333.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Application in other disciplines== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Social work=== | ===Social work=== | ||

| − | In the field of [[social work]], proponents of intersectionality hold that unless service providers take intersectionality into account, they will be of less use for various segments of the population, such as those reporting domestic violence or disabled victims of abuse. According to intersectional theory, the practice of [[domestic violence]] counselors in the [[United States]] urging all women to report their abusers to police is of little use to [[women of color]] due to the history of racially motivated [[police brutality]], and those counselors should adapt their counseling for women of color.<ref>Bent-Goodley, | + | In the field of [[social work]], proponents of intersectionality hold that unless service providers take intersectionality into account, they will be of less use for various segments of the population, such as those reporting domestic violence or disabled victims of abuse. According to intersectional theory, the practice of [[domestic violence]] counselors in the [[United States]] urging all women to report their abusers to police is of little use to [[women of color]] due to the history of racially motivated [[police brutality]], and those counselors should adapt their counseling for women of color.<ref>Tricia B. Bent-Goodley, Lorraine Chase, Elizabeth A. Circo, and Selena T. Antá Rodgers, "Our survival, our strengths: understanding the experiences of African American women in abusive relationships" in Lettie Lockhart and Fran S. Danis (eds.), ''Domestic violence intersectionality and culturally competent practice'' (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0231140270), 77.</ref> |

| − | Women with disabilities encounter more frequent domestic abuse with a greater number of abusers. Health care workers and personal care attendants perpetrate abuse in these circumstances, and women with disabilities have fewer options for escaping the abusive situation.<ref | + | Women with disabilities encounter more frequent domestic abuse with a greater number of abusers. Health care workers and personal care attendants perpetrate abuse in these circumstances, and women with disabilities have fewer options for escaping the abusive situation.<ref>Elizabeth P. Cramer and Sara-Beth Plummer, "Social work practice with abused persons with disabilities," in Lettie Lockhart and Fran S. Danis (eds.), ''Domestic violence intersectionality and culturally competent practice'' (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0231140270), 131.</ref> Chenoweth argues that there is a "silence" principle concerning the intersectionality of women and disability, which maintains an overall social denial of the prevalence of abuse among the disabled which leads to this abuse being frequently ignored.<ref>Lesley Chenoweth, "Violence and women with disabilities: silence and paradox," ''Violence Against Women '' 2(4) (December 1996): 391–411.</ref> |

== Criticism == | == Criticism == | ||

=== Methods and ideology === | === Methods and ideology === | ||

| − | + | Political theorist Rebecca Reilly-Cooper critiques intersectionality's reliance on [[standpoint theory]]. Intersectionality posits that an oppressed person is often the best person to judge their experience of oppression; however, this can create paradoxes when people who have similar experiences nonetheless have different interpretations of similar events. What one views as oppression may not resonate with another. Such paradoxes make it very difficult to synthesize a common actionable cause based on subjective testimony alone. Other narratives, especially those based on multiple intersections of oppression, are more complex.<ref>Liam Kofi Bright, Daniel Malinsky, and Morgan Thompson, "Causally interpreting intersectionality theory," ''Philosophy of Science'' 18(1) (January 2016): 60–81.</ref> Davis asserts that intersectionality is ambiguous and open-ended, and that its "lack of clear-cut definition or even specific parameters has enabled it to be drawn upon in nearly any context of inquiry."<ref>Kathy Davis, "Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful," ''Feminist Theory'' 9(1) (April 2008): 67–85.</ref> | |

| − | + | Lisa Downing argues that intersectionality focuses too much on group identities, which can lead it to ignore the fact that people are individuals, not just members of a class. Ignoring this can cause intersectionality to lead to a simplistic analysis and inaccurate assumptions about how a person's values and attitudes are determined.<ref>Lisa Downing, "The body politic: Gender, the right wing and 'identity category violations'," ''French Cultural Studies'' 29(4) (2018): 367-377.</ref> | |

| − | Barbara Tomlinson | + | Barbara Tomlinson has been critical of the tendency to use intersectional theory to attack other ways of feminist thinking. Tomlinson argues that intersectional feminists must not only consider the arguments but the tradition and mediums through which these arguments are made. Rejecting these traditional approaches can have the impact of favoring weaker arguments that fit the intersectional narrative against those that do not share the framework. This allows critics of intersectionality to attack these weaker arguments, "[reducing] intersectionality's radical critique of power to desires for identity and inclusion, and offer a deradicalized intersectionality as an asset for dominant disciplinary discourses."<ref>Barbara Tomlinson, "To Tell the Truth and Not Get Trapped: Desire, Distance, and Intersectionality at the Scene of Argument," ''Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society'' 38(4) (Summer 2013): 993–1017.</ref> |

| − | + | Rekia Jibrin and Sara Salem, in a Marxist-based critique, argue that intersectional theory creates a unified idea of anti-oppression politics that requires a lot out of its adherents, often more than can reasonably be expected, creating difficulties achieving [[Praxis (process)|praxis]]. They also say that intersectional philosophy encourages a focus on the issues inside the group instead of on society at large, and that intersectionality is "a call to complexity and to abandon oversimplification... this has the parallel effect of emphasizing 'internal differences' over hegemonic structures."<ref>Rekia Jibrin and Sara Salem, "Revisiting intersectionality: reflections on theory and praxis," ''Trans-Scripts: An Interdisciplinary Online Journal in the Humanities and Social Sciences'' 5 (2015).</ref> | |

| − | === | + | ===Transnational intersectionality=== |

| − | + | [[Postcolonial feminism|Third World feminists]] and [[transnational feminism|transnational feminists]] criticize intersectionality as a concept emanating from [[WEIRD]] (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic)<ref>J. Henrich, S. J. Heine, and A. Norenzayan, "The weirdest people in the world?" ''Behavioral and Brain Sciences'' 33(2–3) (2010): 61–83.</ref> societies that unduly universalizes women's experiences.<ref>R. S. Herr, "Reclaiming third world feminism: Or why transnational feminism needs third world feminism," ''Meridians'' 12 (2014): 1–30.</ref><ref>T. Kurtis and G. Adams, "Decolonizing liberation: Toward a transnational feminist psychology," ''Journal of Social and Political Psychology'' 3(2) (2015): 388–413.</ref> Third world feminists have worked to revise Western conceptualizations of intersectionality that assume all women experience the same type of gender and racial oppression.<ref>L. H. Collins, S. Machizawa, and J. K. Rice, ''Transnational Psychology of Women: Expanding International and Intersectional Approaches'' (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2019, ISBN 978-1433830693).</ref> Shelly Grabe coined the term "transnational intersectionality" to represent a more comprehensive conceptualization of intersectionality. Grabe wrote, "Transnational intersectionality places importance on the intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, economic exploitation, and other social hierarchies in the context of empire building or imperialist policies characterized by historical and emergent [[global capitalism]]."<ref>S. Grabe and N. M. Else-Quest, "The role of transnational feminism in psychology: Complementary visions, ''Psychology of Women Quarterly'' 36 (2012): 158–161.</ref> Both Third World and transnational feminists advocate attending to complex and intersecting oppressions and multiple forms of resistance. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Controversy in France=== | |

| + | In France, intersectionality has been denounced as a school of thought imported from the US.<ref>Valentine Faure, [https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2020/12/21/alain-policar-la-fixation-sur-les-origines-tend-a-les-transformer-en-destin_6064047_3232.html "Alain Policar : ' La fixation sur les origines tend à les transformer en destin'"] (Fixating on the origins turns them into fate) ''Le Monde'', December 21, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2022.</ref> The French Minister of Education [[Jean-Michel Blanquer]] declared that intersectionality is in conflict with the French republican values. He accused advocates of intersectionality of playing into the hands of Islamism.<ref>Eric Aeschimann, Xavier de La Porte, and Rémi Noyon, | ||

| + | [https://www.nouvelobs.com/idees/20201026.OBS35242/theses-intersectionnelles-blanquer-vous-explique-tout-mais-n-a-rien-compris.html "Thèses intersectionnelles: Blanquer vous explique tout, mais n'a rien compris,"] (Intersectional Theses: Blanquer explains everything to you, but did not understand anything) ''L'Obs'', October 28, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.</ref> In turn, ''[[Libération]]'' accused Blanquer of not having a good understanding of the concept of intersectionality and of attacking the concept for political reasons.<ref>Rose-Marie Lagrave, [https://www.liberation.fr/debats/2020/11/03/intersectionnalite-blanquer-joue-avec-le-feu_1804309 "Intersectionnalité : Blanquer joue avec le feu,"] (Intersectionality: Blanquer is playing with fire) ''Libération'', November 3, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.</ref> The murder of Samuel Paty, a French secondary school teacher, by an Islamist, led to some attacks on the concept of intersectionality.<ref>Xavier Molénat, [https://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/feu-lintersectionnalite/00094407 "Feu sur l'intersectionnalité!"] (Open fire on intersectionality!) ''Alternatives économiques'', November 6, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | + | Many recent academics, such as [[Leslie McCall]], have argued that the introduction of the intersectionality theory was vital to sociology and that before the development of the theory, there was little research that specifically addressed the experiences of people who are subjected to multiple forms of oppression within society.<ref>Leslie McCall, "The complexity of intersectionality," ''Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society'' 30(3) (Spring 2005): 1771–1800.</ref> An example of this idea was championed by [[Iris Marion Young]], arguing that differences must be acknowledged in order to find unifying social justice issues that create coalitions that aid in changing society for the better.<ref>Anna Carastathis, ''Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons'' (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0803285552).</ref> More specifically, this relates to the ideals of the [[National Council of Negro Women]] (NCNW).<ref>Ruth Caston Mueller, "The National Council of Negro Women, Inc.," ''Negro History Bulletin'' 18(2) (1954): 27–31.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | * Carastathis, Anna. ''Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons''. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0803285552 | ||

| + | * Chow, Esther Ngan-ling, Marcia Texler Segal, and Tan Lin (eds.). ''Analysing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts''. Bingley, England: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2011. ISBN 978-0857247438 | ||

| + | * Collins, Patricia Hill. ''Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment''. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0415924832 | ||

| + | * Collins, L. H., S. Machizawa, and J. K. Rice. ''Transnational Psychology of Women: Expanding International and Intersectional Approaches''. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2019. ISBN 978-1433830693 | ||

| + | * Crenshaw, Kimberlé. [https://philpapers.org/archive/CREDTI.pdf "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,"] ''University of Chicago Legal Forum'', 1989. Retrieved March 22, 2022. | ||

| + | * Crenshaw, Kimberlé. "Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color," ''Stanford Law Review'' 43(6), July 1991, 1241–1299. | ||

| + | * Crenshaw, Kimberlé. [https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality "The urgency of intersectionality,"] ''ted.com'', October 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2022. | ||

| + | * D'Agostino, Maria, and Helisse Levine. ''Women in Public Administration: Theory and practice''. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011. ISBN 0763777250 | ||

| + | * hooks, bell. ''Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism''. London, England and Boston, MA: Pluto Press South End Press, 1981. ISBN 978-1138821514 | ||

| + | * hooks, bell. ''Feminist Theory: from margin to center'' 3rd. ed. New York, NY: Routledge Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1138821668 | ||

| + | * Kidd, Ian James, Jose Medina, and Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr. (eds.), ''The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice''. London, England: Routledge, 2019. ISBN 978-0367370633 | ||

| + | * Lemert, Charles (ed.). ''Social Theory: The Multicultural, Global, and Classic Readings'', 7th edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0367272661 | ||

| + | * Lockhart, Lettie, and Fran S. Danis (eds.). ''Domestic Violence Intersectionality and Culturally Competent Practice''. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0231140270 | ||

| + | * Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (eds.). ''This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by radical women of color'' 4th ed. Albany, NY: State University of New York (SUNY) Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1438454382 | ||

| + | * Ritchie, Joy, and Kate Ronald (eds.). ''Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric(s)''. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0822957539 | ||

| + | * Ritzer, George, and Jeffrey Stepnisky. ''Contemporary Sociological Theory and its Classical Roots: The basics''. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2013. ISBN 978-0078026782 | ||

| + | * Schiek, Dagmar, and Anna Lawson (eds.). ''European Union Non-Discrimination Law and Intersectionality: Investigating the Triangle of Racial, Gender and Disability Discrimination''. Abingdon, UK: Routledge Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0754679806 | ||

| + | * Wiegman, Robyn. ''Object Lessons''. Durham, NC; Duke University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0822351603 | ||

| + | * Wood, Julia T., and Natalie Fixmer-Oraiz. ''Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture''. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2015. ISBN 978-1305280274 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved March 16, 2022. | |

| − | + | *[https://archive.org/stream/DemarginalizingTheIntersectionOfRaceAndSexABlackFeminis/Demarginalizing%20the%20Intersection%20of%20Race%20and%20Sex_%20A%20Black%20Feminis_djvu.txt "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics"], by [[Kimberlé Crenshaw]], 1989 | |

| − | * [https://archive.org/stream/DemarginalizingTheIntersectionOfRaceAndSexABlackFeminis/Demarginalizing%20the%20Intersection%20of%20Race%20and%20Sex_%20A%20Black%20Feminis_djvu.txt "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics"], by [[Kimberlé Crenshaw]], 1989 | ||

*[http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/252.html Black Feminist Thought in the Matrix of Domination] | *[http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/252.html Black Feminist Thought in the Matrix of Domination] | ||

| − | |||

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20100603050033/http://www.rpi.edu/%7Eeglash/eglash.dir/SST/bft.htm A Brief History of Black Feminist Thought] | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20100603050033/http://www.rpi.edu/%7Eeglash/eglash.dir/SST/bft.htm A Brief History of Black Feminist Thought] | ||

| − | |||

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20170423171506/https://www.sfu.ca/iirp/documents/resources/101_Final.pdf Intersectionality 101] | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20170423171506/https://www.sfu.ca/iirp/documents/resources/101_Final.pdf Intersectionality 101] | ||

{{credit|979857100}} | {{credit|979857100}} | ||

| + | [[category: Politics and social sciences]] | ||

| + | [[category: Politics]] | ||

| + | [[category: Sociology]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:41, 6 March 2024

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework for understanding discrimination from multiple sources. It identifies advantages and disadvantages that are felt by people due to a combination of factors. For example, a black woman might face discrimination from a business that is not distinctly due to her race (because the business does not discriminate against black men) nor distinctly due to her gender (because the business does not discriminate against white women), but due to a combination of the two factors.

The term was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in a 1989 essay. Since that time it has had an impact on both feminism and the social sciences in general. It is based on the view that race, gender and class are the major determinants of identity, and that minorities from each of these categories are oppressed. Those individuals who are members of more than one of these groups face unique combinations of oppression.

Intersectionality has been critiqued as inherently ambiguous based on its utilization of postmodernist theories of power and the view that the subjective experience of the person who feels oppressed authenticates the oppression. The ambiguity of this theory means that it can be perceived as unorganized and lacking a clear set of defining goals. As it is based in standpoint theory, critics say the focus on subjective experiences can lead to contradictions and the inability to identify common causes of oppression.

Definition

The term was introduced in a 1989 essay by Kimberlé Crenshaw, entitled "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics."[1] Intersectionality is a qualitative analytic framework developed in the late 20th century that identifies how interlocking systems of power affect those who are most marginalized in society[2] and takes these relationships into account to analyze social and political equity.[3] It is a theoretical framework that is generally applied to the ways that social and political identities[4][5] height,[6] etc.) combine to create unique modes of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality expands the lens of the first and second waves of feminism, which largely focused on the experiences of women who were both white and middle-class, to include the different experiences of women of color, women in poverty, immigrants, and other groups. Intersectional feminism aims to separate itself from white feminism by acknowledging women's different experiences and identities.

Intersectionality critiques analytical systems that treat each oppressive factor in isolation, asserting that discrimination against black women is not a simple sum of the discrimination against black men and the discrimination against white women.[7]

Historical Background

The ideas behind intersectional feminism existed long before the term was coined. Sojourner Truth's 1851 "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, for example, suggests themes found in intersectionality, speaking as a former slave to critique essentialist notions of femininity.[8][9]Similarly, in her 1892 essay, "The Colored Woman's Office", Anna Julia Cooper identifies black women as the most important actors in social change movements, because of their experience with multiple facets of oppression.[10]

The term also has historical and theoretical links to the concept of "simultaneity," which was promoted during the 1970s by members of the Combahee River Collective in Boston, Massachusetts.[11] Simultaneity refers to the simultaneous influences of race, class, gender, and sexuality, which informed the member's lives and their resistance to oppression.[12] The women of the Combahee River Collective advanced an understanding of African-American experiences that challenged analyses emerging from Black and male-centered social movements, as well as those from mainstream cisgender, white, middle-class, heterosexual feminists.[13]

Patricia Hill Collins has located the origins of intersectionality among black feminists, Chicana and other Latina feminists, indigenous feminists and Asian American feminists in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and noted the existence of intellectuals at other times and in other places who discussed similar ideas about the interaction of different forms of inequality, such as Stuart Hall and the cultural studies movement, Nira Yuval-Davis, Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. Wells. She noted that as second-wave feminism receded in the 1980s, feminists of color such as Audre Lorde, Gloria E. Anzaldúa and Angela Davis entered academic environments and brought their perspectives to their scholarship. During this decade many of the ideas that would together be labeled as "intersectionality" coalesced in U.S. academia under the banner of "race, class and gender studies."[14]

W. E. B. Du Bois theorized that the intersectional paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain certain aspects of the black political economy. Sociologist Patrcia Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."[15] Du Bois omitted gender from his theory and considered it more of a personal identity category.

In 1981 Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa published the first edition of This Bridge Called My Back. This anthology explored how classifications of sexual orientation and class also mix with those of race and gender to create even more distinct political categories. Many black, Latina, and Asian writers featured in the collection stress how their sexuality interacts with their race and gender to inform their perspectives. Similarly, poor women of color detail how their socio-economic status adds a layer of nuance to their identities, ignored or misunderstood by middle-class white feminists.[16]

Intersectionality and Feminism

The concept of intersectionality addressed dynamics that were previously overlooked by feminist theory and movements.[17] Racial inequality was a factor that was largely ignored by first-wave feminism, which was primarily concerned with gaining political equality between white men and white women. Early women's rights movements often exclusively pertained to the membership, concerns, and struggles of white women.[18] Second-wave feminism stemmed from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and worked to dismantle sexism relating to the perceived domestic purpose of women. While feminists during this time achieved success through the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade, they largely alienated black women from platforms in the mainstream movement.[19] However, third-wave feminism—which emerged shortly after the term "intersectionality" was coined in the late 1980s—noted the lack of attention to race, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity in early feminist movements, and tried to provide a channel to address political and social disparities.[20]

According to black feminists and many white feminists, experiences of class, gender, and sexuality cannot be adequately understood unless the influence of racialization is carefully considered. This focus on racialization was highlighted many times by scholar and feminist bell hooks, specifically in her 1981 book Ain't I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism.[21] Feminists argue that an understanding of intersectionality is a vital element of gaining political and social equality and improving our democratic system.[22] Collins's theory represents the sociological crossroads between modern and post-modern feminist thought.[15]

Author bell hooks, argued that the emergence of intersectionality "challenged the notion that 'gender' was the primary factor determining a woman's fate."[23] The historical exclusion of black women from the feminist movement in the United States resulted in many black 19th and 20th century feminists, such as Anna Julia Cooper, challenging their historical exclusion. They disputed the ideas of earlier feminist movements, which were primarily led by white middle-class women, suggesting that women were a homogeneous category who shared the same life experiences.[24] The forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women were different from those experienced by black, poor, or disabled women. Feminists could then begin seeking ways to understand how gender, race, and class combine to "determine the female destiny."[23]

Introduction of the idea

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw

The term was coined by black feminist scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989. Crenshaw introduced the theory of intersectionality in her 1989 paper written for the University of Chicago Legal Forum, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics."[1][25] The main argument is that the experience of black women cannot be understood by examining black experience or a woman's experience independently. It must include the interactions between the two, which frequently reinforce each other.[26]

In order to show that non-white women have a vastly different experience from white women due to their race and/or class and that their experiences are not easily voiced or amplified, Crenshaw explores two types of male violence against women: domestic violence and rape. Through her analysis of these two forms of male violence against women, Crenshaw says that the experiences of non-white women consist of a combination of both racism and sexism. The argument is that because non-white women are present within discourses that have been designed to address either race or sex separately, non-white women are marginalized within both of these systems of oppression.[27]

In her work, Crenshaw identifies three aspects of intersectionality that affect the visibility of non-white women: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence and rape in a manner qualitatively different than that of white women. Political intersectionality examines how laws and policies intended to increase equality have paradoxically decreased the visibility of violence against non-white women. Finally, representational intersectionality delves into how pop culture portrayals of non-white women can obscure their own authentic lived experiences.

The theory began as an explanation of the oppression of women of color within society. The analysis has expanded to include many more aspects of social identity. Identities most commonly referenced in the fourth wave of feminism include race, gender, sex, sexuality, class, ability, nationality, citizenship, religion and body type. The term Intersectionality was not adopted widely by feminists until the 2000s.

Patricia Hill Collins

Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins refers to the various intersections of social inequality as the matrix of domination. These are also known as "vectors of oppression and privilege."[28] She developed the concept primarily to apply to the experience of African-American women. Intersectionality, Collins says, replaced her own previous coinage "black feminist thought," and "increased the general applicability of her theory from African American women to all women."[29] Much like Crenshaw, Collins argues that cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society, such as race, gender, class, and ethnicity.[15] Collins describes this as "interlocking social institutions [that] have relied on multiple forms of segregation... to produce unjust results".[30]

Collins sought to create frameworks to think about intersectionality, rather than expanding on the theory itself. She identified three main branches of study within intersectionality. One branch deals with the background, ideas, issues, conflicts, and debates within intersectionality. Another branch seeks to apply intersectionality as an analytical strategy to various social institutions in order to examine how they might perpetuate social inequality. The final branch formulates intersectionality as a critical praxis to determine how social justice initiatives can use intersectionality to bring about social change.[14]

Speaking from a critical standpoint, Collins points out that Brittan and Maynard say that "domination always involves the objectification of the dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity of the oppressed."[31] She later notes that self-valuation and self-definition are two ways of resisting oppression. Practicing self-awareness helps to preserve the self-esteem of the group that is being oppressed and allows them to avoid any dehumanizing outside influences.

Intersectionality and Postmodernism

Crenshaw, Collins, and other theorists who have shaped intersectionality rely on a postmodern view of race and gender as socially constructed. Their theories adopted the postmodern view of power structures advocated by Michel Foucault and his followers. Foucault argued that power structures favored privileged groups within society. He critiqued the idea that power could be neutral, or that their was a common heritage to which we could all ascribe and aspire. Different groups all have a different experience of the power structure. Their experience is socially-constructed by that experience. But while Foucault and other promoters of postmodernism tended to focus on the limits of power, Crenshaw argues that these socially-constructed identities should be seen as the location of political empowerment and community building. There are several intertwined postmodern theories on which intersectionality is built.

Intersectionality and Critical Race Theory

Intersectionality has a number of antecedents. Key among them is Critical Race Theory. Critical Race Theory developed within legal studies starting in the 1970s. It was pioneered by Law Professor Derek Bell at Harvard, whose students included Kimberlé Crenshaw. Critical Race Theory began by focusing on issues of discrimination and addressing poverty. Bell, Richard Delgado, and other legal scholars had a more materialist focus. However, in the intervening period between the 1970s and the 1990s, postmodernism became more popular within academia. Crenshaw and other scholars influenced by postmodernism shifted the focus of Critical Race Theory from a more Marxist basis, to one based on postmodernism and questions of identity.

On identity, Crenshaw distinguishes the difference between the older, civil rights approach and one based on a new one rooted in identity politics:

We can call recognize the distinction between the claim, "I am Black" and the claim "I am a person who happens to be Black." "I am Black" takes the socially imposed identity and empowers it as an anchor of subjectivity. "I am Black" becomes not simply a statement of resistance but also a positive discourse of self-identification, intimately linked to celebratory statement like the Black nationalist "Black is beautiful."[27]

Crenshaw explicitly rejects the statement "I am a person who happens to be Black," which had been the formulation of the liberal inclusion agenda in favor of embracing the socially constructed racial category as a self-identification.

Intersectionality and Identity politics

The focus on self-identification based on socially-constructed identities is an explicit rejection of the earlier liberal civil rights model. Civil rights is grounded in the liberal view of equality of opportunity. The goal of civil rights had been removing barriers that prevented racial minorities from equal access, such as voting rights, integration of schools, affirmative action, and other policies designed to give minorities the same opportunities. In its place, intersectionality explicitly embraces identity politics. For Crenshaw, "identity-based politics has been a source of strength, community and intellectual development."[27]

Marginalized groups often gain a status of being an "other." In essence, you are "an other" if you are different from what Audre Lorde calls the mythical norm. Gloria Anzaldúa theorizes that the sociological term for this is "othering," or specifically attempting to establish a person as unacceptable based on a certain criterion that fails to be met.[32]

Standpoint Theory

Based on the postmodern rejection of Enlightenment concepts of truth and power, intersectionality accepts that the socially constructed position gives each group in society a different standpoint. Standpoint theory claims that one's experience of either dominance or oppression depends on one's standpoint within the hierarchy of power. Based on that standpoint, it also argues that those who are in oppressed groups can see the power relations in a way that the dominant groups cannot. People in a position of power are said to be privileged. Further, they do not know their own privilege. Those are are said to be oppressed know not only their own standpoint, but the privilege of those in positions of power.

Patricia Hill Collins argues that standpoint epistemology and identity politics are the two tools for those who are marginalized to speak their truth. Standpoint theory gives them the epistemic authority and identity politics the platform on which to state it.[33]

Both Collins and Dorothy Smith have been instrumental in providing a sociological definition of standpoint theory. Individuals who share an identity status are said to have a common experience which shapes a common perspective. Knowledge is subjective and unique to each socially-constructed identity group; it varies depending on the social conditions under which it was produced.[34]

Collins argues that these socially-constructed identities means that even successful minorities remain the other in society. For example, a Black woman, may become influential in a particular field, she may feel as though she does not belong. Their personalities, behavior, and cultural being overshadow their value as an individual; thus, they become the outsider within.[31] As people move from a common cultural world (i.e., family) to that of modern society.[35]

Intersectionality in a global context

Over the last couple of decades in the European Union (EU), there has been discussion regarding the intersections of social classifications. Before Crenshaw coined her definition of intersectionality, there was a debate on what these societal categories were. The categorization between gender, race, and class has turned into a multidimensional intersection of "race" including religion, sexuality, ethnicities, etc. In the EU and UK, they refer to these intersections under the notion of multiple discrimination. The EU passed a non-discrimination law which addresses these multiple intersections; however, there is debate on whether the law is still proactively focusing on the proper inequalities.[36]

Outside of the EU, intersectional categories have also been considered. In Analysing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts, the authors argue: "The impact of patriarchy and traditional assumptions about gender and families are evident in the lives of Chinese migrant workers (Chow, Tong), sex workers and their clients in South Korea (Shin), and Indian widows (Chauhan), but also Ukrainian migrants (Amelina) and Australian men of the new global middle class (Connell)." This text argues for many more intersections of discrimination for people around the globe than Crenshaw originally accounted for in her definition.[37]

Chandra Mohanty discusses alliances between women throughout the world as intersectionality in a global context. She rejects the western feminist theory, especially when it writes about global women of color and generally associated "third world women." She argues that "third world women" are often thought of as a homogenous entity, when, in fact, their experience of oppression is informed by their geography, history, and culture. When western feminists write about women in the global South in this way, they dismiss the inherent intersecting identities that are present in the dynamic of feminism in the global South. Mohanty questions the performance of intersectionality and relationality of power structures within the US and colonialism and how to work across identities with this history of colonial power structures.[38]

Application in other disciplines

Social work

In the field of social work, proponents of intersectionality hold that unless service providers take intersectionality into account, they will be of less use for various segments of the population, such as those reporting domestic violence or disabled victims of abuse. According to intersectional theory, the practice of domestic violence counselors in the United States urging all women to report their abusers to police is of little use to women of color due to the history of racially motivated police brutality, and those counselors should adapt their counseling for women of color.[39]

Women with disabilities encounter more frequent domestic abuse with a greater number of abusers. Health care workers and personal care attendants perpetrate abuse in these circumstances, and women with disabilities have fewer options for escaping the abusive situation.[40] Chenoweth argues that there is a "silence" principle concerning the intersectionality of women and disability, which maintains an overall social denial of the prevalence of abuse among the disabled which leads to this abuse being frequently ignored.[41]

Criticism

Methods and ideology

Political theorist Rebecca Reilly-Cooper critiques intersectionality's reliance on standpoint theory. Intersectionality posits that an oppressed person is often the best person to judge their experience of oppression; however, this can create paradoxes when people who have similar experiences nonetheless have different interpretations of similar events. What one views as oppression may not resonate with another. Such paradoxes make it very difficult to synthesize a common actionable cause based on subjective testimony alone. Other narratives, especially those based on multiple intersections of oppression, are more complex.[42] Davis asserts that intersectionality is ambiguous and open-ended, and that its "lack of clear-cut definition or even specific parameters has enabled it to be drawn upon in nearly any context of inquiry."[43]

Lisa Downing argues that intersectionality focuses too much on group identities, which can lead it to ignore the fact that people are individuals, not just members of a class. Ignoring this can cause intersectionality to lead to a simplistic analysis and inaccurate assumptions about how a person's values and attitudes are determined.[44]

Barbara Tomlinson has been critical of the tendency to use intersectional theory to attack other ways of feminist thinking. Tomlinson argues that intersectional feminists must not only consider the arguments but the tradition and mediums through which these arguments are made. Rejecting these traditional approaches can have the impact of favoring weaker arguments that fit the intersectional narrative against those that do not share the framework. This allows critics of intersectionality to attack these weaker arguments, "[reducing] intersectionality's radical critique of power to desires for identity and inclusion, and offer a deradicalized intersectionality as an asset for dominant disciplinary discourses."[45]

Rekia Jibrin and Sara Salem, in a Marxist-based critique, argue that intersectional theory creates a unified idea of anti-oppression politics that requires a lot out of its adherents, often more than can reasonably be expected, creating difficulties achieving praxis. They also say that intersectional philosophy encourages a focus on the issues inside the group instead of on society at large, and that intersectionality is "a call to complexity and to abandon oversimplification... this has the parallel effect of emphasizing 'internal differences' over hegemonic structures."[46]

Transnational intersectionality

Third World feminists and transnational feminists criticize intersectionality as a concept emanating from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic)[47] societies that unduly universalizes women's experiences.[48][49] Third world feminists have worked to revise Western conceptualizations of intersectionality that assume all women experience the same type of gender and racial oppression.[50] Shelly Grabe coined the term "transnational intersectionality" to represent a more comprehensive conceptualization of intersectionality. Grabe wrote, "Transnational intersectionality places importance on the intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, economic exploitation, and other social hierarchies in the context of empire building or imperialist policies characterized by historical and emergent global capitalism."[51] Both Third World and transnational feminists advocate attending to complex and intersecting oppressions and multiple forms of resistance.

Controversy in France

In France, intersectionality has been denounced as a school of thought imported from the US.[52] The French Minister of Education Jean-Michel Blanquer declared that intersectionality is in conflict with the French republican values. He accused advocates of intersectionality of playing into the hands of Islamism.[53] In turn, Libération accused Blanquer of not having a good understanding of the concept of intersectionality and of attacking the concept for political reasons.[54] The murder of Samuel Paty, a French secondary school teacher, by an Islamist, led to some attacks on the concept of intersectionality.[55]

Legacy

Many recent academics, such as Leslie McCall, have argued that the introduction of the intersectionality theory was vital to sociology and that before the development of the theory, there was little research that specifically addressed the experiences of people who are subjected to multiple forms of oppression within society.[56] An example of this idea was championed by Iris Marion Young, arguing that differences must be acknowledged in order to find unifying social justice issues that create coalitions that aid in changing society for the better.[57] More specifically, this relates to the ideals of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW).[58]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kimberlé Crenshaw, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics," University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Brittney Cooper, Mary Hawkesworth, and Lisa Disch, The Journal of Intersectionality vol. 1, February 1, 2016.

- ↑ What Does Intersectional Feminism Actually Mean?," International Women's Development Agency, May 11, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Abigail Tucker, "How Much is Being Attractive Worth?" Smithsonian Magazine, November 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Kelsey Yonce, "Attractiveness privilege : the unearned advantages of physical attractiveness," Theses, Dissertations, and Projects, January 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Omer Kimhi, "Falling Short – the Discrimination of Height Discrimination,", April 22, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Kimberlé Crenshaw, "The urgency of intersectionality,". Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ↑ Sojourner Truth, "Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio" (1851) in Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric(s), Joy Ritchie and Kate Ronald, eds., (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0822957539), 144-146.

- ↑ Avtar Brah and Ann Phoenix, "Ain't I A Woman? Revisiting intersectionality," Journal of International Women's Studies 5(3), 2004, 75–86. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Anna Julia Cooper, "The colored woman's office" in Social theory: the multicultural, global, and classic readings, 6th edition, Charles Lemert ed., (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0813350448).

- ↑ Robyn Wiegman, Object lessons (Durham, NC; Duke University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0822351603), 244.

- ↑ Amanda Walker Johnson, "Resituating the Crossroads: Theoretical Innovations in Black Feminist," Souls 19(4), October 2, 2017, 401–415.

- ↑ Brian Norman, "'We' in Redux: The Combahee River Collective's Black Feminist Statement," Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18(2), 2007: 104.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Patricia Hill Collins, "Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas," Annual Review of Sociology 41 (2015): 1–20.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Patricia Hill Collins, "Gender, black feminism, and black political economy," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568(1) (March 2000): 41–53.

- ↑ Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (eds.), This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color 4th ed. (Albany, NY: State University of New York (SUNY) Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1438454382).

- ↑ Becky Thompson, "Multiracial feminism: recasting the chronology of Second Wave Feminism," Feminist Studies 28(2) (Summer 2002): 337–360.

- ↑ Julia T. Wood and Natalie Fixmer-Oraiz, Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2015, ISBN 978-1305280274), 59–60.

- ↑ Constance Grady, "The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained," Vox, July 20, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ↑ Wood and Fixmer-Oraiz, 72–73.

- ↑ bell hooks, Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (London, England and Boston, MA: Pluto Press South End Press, 1981, ISBN 978-1138821514).

- ↑ Maria D'Agostino and Helisse Levine, Women in Public Administration: Theory and practice (Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011, ISBN 0763777250), 8.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 bell hooks, Feminist Theory: from margin to center 3rd. ed., (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 978-1138821668).

- ↑ Angela Davis, Women, Race & Class (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1983, ISBN 978-0394713519).

- ↑ "Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later," Columbia Law School, June 8, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ↑ Sheila Thomas and Kimberlé Crenshaw, "Intersectionality: the double bind of race and gender," Perspectives Magazine, American Bar Association, Spring 2004, 2.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, "Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color," Stanford Law Review 43(6) (July 1991): 1241–1299.