Difference between revisions of "Intelligence test" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

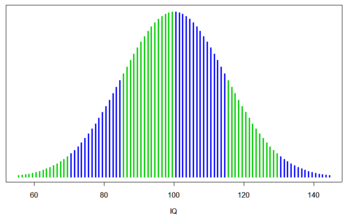

[[Image:IQ_curve.png|thumb|350px|IQ tests are designed to give approximately this Gaussian distribution. Colors delineate one standard deviation. But the true frequency of low and high IQs is greater than that given by the Gaussian curve.]] | [[Image:IQ_curve.png|thumb|350px|IQ tests are designed to give approximately this Gaussian distribution. Colors delineate one standard deviation. But the true frequency of low and high IQs is greater than that given by the Gaussian curve.]] | ||

| − | An '''intelligence quotient''' or '''IQ''' is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtests scores. Regardless of design, all IQ tests measure the same general intelligence factor also referred to as "g" | + | An '''intelligence quotient''' or '''IQ''' is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtests scores. Regardless of design, all IQ tests measure the same general intelligence factor also referred to as "g." Component tests are generally designed and chosen because they are found to be predictable of later intellectual development. In some studies, IQ has been shown to correlate with job performance, socioeconomic advancement, and other "social pathologies." Recent work has demonstrated links between IQ and health, longevity, and functional literacy. However, IQ tests have engendered much controversy and it is important to note that they do not measure all meanings of "intelligence." IQ scores are relative. Meaning, that the placement of an IQ score is similar to a placement in a race as they are both dependent upon the performance of the other participants. |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | In 1905, the French psychologist Alfred Binet published the first modern | + | In 1905, the French [[psychologist]] [[Alfred Binet]] published the first modern test of [[intelligence]]. His principal goal was to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school [[curriculum]]. Along with his collaborator [[Theodore Simon]], Binet published revisions of his Binet-Simon intelligence scale in 1908 and 1911, the last appearing just before his untimely death. In 1912, the abbreviation of "intelligence quotient" or IQ, a translation of the German ''Intelligenz-quotient'', was coined by the German psychologist [[William Stern]]. |

| − | A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by Lewis M. Terman, from Stanford University, who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient ( | + | A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by [[Lewis M. Terman]], from [[Stanford University]], who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient (IQ). Terman's test, which he named the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale formed the basis for one of the modern intelligence tests still commonly used today. |

| − | + | Originally, IQ was calculated as a ratio with the formula <math>100 \times \frac{\text{mental age}}{\text{chronological age}}.</math> | |

| − | + | A 10-year-old who scored as high as the average 13-year-old, for example, would have an IQ of 130 (100*13/10). | |

| − | + | In 1939 [[David Wechsler]] published the first intelligence test explicitly designed for an adult population, the [[Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale]], or WAIS. Since publication of the WAIS, Wechsler extended his scale downward to create the [[Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children]], or WISC. The third edition of the WAIS (WAIS-III) is the most widely used psychological test in the world, and the fourth edition of the WISC (WISC-IV) is the most widely used intelligence test for children. The Wechsler scales contained separate subscores for verbal and performance IQ, thus being less dependent on overall verbal ability than early versions of the Stanford-Binet scale, and was the first intelligence scale to base scores on a standardized [[normal distribution]] rather than an age-based quotient. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Since the publication of the WAIS, almost all intelligence scales have adopted the normal distribution method of scoring. The use of the normal distribution scoring method makes the term "intelligence quotient" an inaccurate description of the intelligence measurement, but "IQ" still enjoys colloquial usage, and is used to describe all of the intelligence scales currently in use. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==IQ testing== | ||

| + | ===Structure=== | ||

| + | IQ tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question, while others use several different subtests. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A typical IQ test requires the test subject to solve a fair number of problems in a set time under supervision. Most IQ tests include items from various domains, such as short-term memory, verbal knowledge, spatial visualization, and perceptual speed. Some tests have a total time limit, others have a time limit for each group of problems, and there are a few untimed, unsupervised tests, typically geared to measuring high intelligence. The widely used standardized test for determining IQ, the [[Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale|WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition]] (WAIS-III), consists of fourteen subtests, seven verbal (Information, Comprehension, Arithmetic, Similarities, Vocabulary, Digit Span, and Letter-Number Sequencing) and seven performance (Digit Symbol-Coding, Picture Completion, Block Design, Matrix Reasoning, Picture Arrangement, Symbol Search, and Object Assembly). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Scoring=== | ||

| + | When standardizing an IQ test, a representative sample of the population is tested using each test question. IQ tests are calibrated in such a way as to yield a normal distribution, or "bell curve." Each IQ test, however, is designed and valid only for a certain IQ range. Because so few people score in the extreme ranges, IQ tests usually cannot accurately measure very low and very high IQs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Various IQ tests measure a standard deviation with a different number of points. Thus, when an IQ score is stated, the standard deviation used should also be stated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When an individual has scores that do not correlate with each other, there is a good reason to suspect a learning disability or other cause for this lack of correlation. Tests have been chosen for inclusion because they display the ability to use this method to predict later difficulties in learning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An individual's IQ score may or may not be stable over the course of the individual's lifetime.<ref name="Neisser95">{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.lrainc.com/swtaboo/taboos/apa_01.html | ||

| + | |title=Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=August 7, 1995 | ||

| + | |author=Neisser ''et al.'' | ||

| + | |publisher=Board of Scientific Affairs of the [[American Psychological Association]] | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === IQ and general intelligence factor === | ||

| + | {{main|General intelligence factor}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Modern IQ tests produce scores for different areas (e.g., language fluency, three-dimensional thinking), with the summary score calculated from subtest scores. The average score, according to the bell curve, is 100. Individual subtest scores tend to [[correlation|correlate]] with one another, even when seemingly disparate in content. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mathematical analysis of individuals' scores on the subtests of a single IQ test or the scores from a variety of different IQ tests (e.g., [[Stanford-Binet]], [[WISC-R]], [[Raven's Progressive Matrices]], [[Cattell Culture Fair III]], Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test, Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, and others) find that they can be described mathematically as measuring a single common factor and various factors that are specific to each test. This kind of [[factor analysis]] has led to the theory that underlying these disparate cognitive tasks is a single factor, termed the [[general intelligence factor]] (or ''g''), that corresponds with the common-sense concept of intelligence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/~reingold/courses/intelligence/cache/1198gottfred.html | ||

| + | |title=The General Intelligence Factor | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=[[1998-11]] | ||

| + | |author=Linda S. Gottfredson | ||

| + | |publisher=Scientific American | ||

| + | }}</ref> In the normal population, ''g'' and IQ are roughly 90% correlated and are often used interchangeably. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tests differ in their ''g''-loading, which is the degree to which the test score reflects ''g'' rather than a specific skill or "group factor" (such as verbal ability, spatial visualization, or mathematical reasoning). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Mental handicaps=== | ||

| + | {{main|Mental retardation}} | ||

| + | Individuals with an unusually low IQ score, varying from about 70 ("Educable Mentally Retarded") to as low as 20 (usually caused by a neurological condition), are considered to have developmental difficulties. However, there is no true IQ-based classification for [[Developmental disability|developmental disabilities]]. | ||

==Practical validity== | ==Practical validity== | ||

| Line 25: | Line 65: | ||

Evidence for the practical validity of IQ has been suggested through the examination of the correlation between IQ scores and economic and social indicators of valued life outcomes. | Evidence for the practical validity of IQ has been suggested through the examination of the correlation between IQ scores and economic and social indicators of valued life outcomes. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between ''[[g (factor)|g]]'' and life outcomes are pervasive, despite the fact that IQ and happiness are not correlates. IQ and ''g'' correlate highly with school performance and job performance, moderately with income, and to a small degree whether or not the individual will abide by the law. | Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between ''[[g (factor)|g]]'' and life outcomes are pervasive, despite the fact that IQ and happiness are not correlates. IQ and ''g'' correlate highly with school performance and job performance, moderately with income, and to a small degree whether or not the individual will abide by the law. | ||

| − | General intelligence whhich in the literature is typically called "cognitive ability" is the best predictor of job performance by the standard measure of validity. ''Validity'' is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure), and ranges between −1.0 (the score is perfectly wrong in predicting outcome) and 1.0 (the score perfectly predicts the outcome) | + | General intelligence whhich in the literature is typically called "cognitive ability" is the best predictor of job performance by the standard measure of validity. ''Validity'' is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure), and ranges between −1.0 (the score is perfectly wrong in predicting outcome) and 1.0 (the score perfectly predicts the outcome). The validity of cognitive ability for job performance tends to increase with job complexity and varies across different studies, ranging from 0.2 for unskilled jobs to 0.8 for the most complex jobs. |

A meta-analysis (Hunter and Hunter, 1984) which pooled validity results across many studies encompassing thousands of workers (32,124 for cognitive ability), reports that the validity of cognitive ability for entry-level jobs is 0.54, larger than any other measure including job tryout (0.44), experience (0.18), interview (0.14), age (−0.01), education (0.10), and biographical inventory (0.37). | A meta-analysis (Hunter and Hunter, 1984) which pooled validity results across many studies encompassing thousands of workers (32,124 for cognitive ability), reports that the validity of cognitive ability for entry-level jobs is 0.54, larger than any other measure including job tryout (0.44), experience (0.18), interview (0.14), age (−0.01), education (0.10), and biographical inventory (0.37). | ||

| Line 102: | Line 92: | ||

Nearly all personality traits show that, contrary to expectations, environmental effects actually cause adoptive siblings raised in the same family to be as different as children who were raised in different families (Harris, 1998; Plomin & Daniels, 1987). IQ is an exception among children. The IQs of adoptive siblings, who share no genetic relation but do share a common family environment, are correlated at .32. Despite attempts to isolate the factors that cause adoptive siblings to be similar, they have not been identified. It is important to note, however, that shared family effects on IQ disappear after adolescence. | Nearly all personality traits show that, contrary to expectations, environmental effects actually cause adoptive siblings raised in the same family to be as different as children who were raised in different families (Harris, 1998; Plomin & Daniels, 1987). IQ is an exception among children. The IQs of adoptive siblings, who share no genetic relation but do share a common family environment, are correlated at .32. Despite attempts to isolate the factors that cause adoptive siblings to be similar, they have not been identified. It is important to note, however, that shared family effects on IQ disappear after adolescence. | ||

| − | Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture" | + | Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture," is observed for IQ. This phenomenon is measured similarly to heritability; but instead of measuring variation in IQ due to genes, variation in environment due to genes is determined. One study found that 40% of variation in measures of home environment are accounted for by genetic variation. This suggests that the way human beings craft their environment is due in part to genetic influences. |

A study of French children adopted between the ages of 4 and 6 shows the continuing interplay of nature and nurture. The children came from poor backgrounds with I.Q.’s that averaged 77, putting them near retardation. Nine years later after adoption, they retook the I.Q. tests, and all of them did better. The amount they improved was directly related to the adopting family’s status. "Children adopted by farmers and laborers had average I.Q. scores of 85.5; those placed with middle-class families had average scores of 92. The average I.Q. scores of youngsters placed in well-to-do homes climbed more than 20 points, to 98."[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/magazine/23wwln_idealab.html?ei=5090&en=2c93740d624fe47f&ex=1311307200&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss&pagewanted=all] This study suggests that IQ is not stable over the course of ones lifetime and that, even in later childhood, a change in individual's environment can have a significant effect on IQ. | A study of French children adopted between the ages of 4 and 6 shows the continuing interplay of nature and nurture. The children came from poor backgrounds with I.Q.’s that averaged 77, putting them near retardation. Nine years later after adoption, they retook the I.Q. tests, and all of them did better. The amount they improved was directly related to the adopting family’s status. "Children adopted by farmers and laborers had average I.Q. scores of 85.5; those placed with middle-class families had average scores of 92. The average I.Q. scores of youngsters placed in well-to-do homes climbed more than 20 points, to 98."[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/magazine/23wwln_idealab.html?ei=5090&en=2c93740d624fe47f&ex=1311307200&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss&pagewanted=all] This study suggests that IQ is not stable over the course of ones lifetime and that, even in later childhood, a change in individual's environment can have a significant effect on IQ. | ||

| Line 130: | Line 120: | ||

Research in Scotland has shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long [http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/health/newsid_1260000/1260794.stm]. | Research in Scotland has shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long [http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/health/newsid_1260000/1260794.stm]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Criticism and views== |

| + | ===Binet=== | ||

| + | [[Alfred Binet]] did not believe that IQ test scales qualified to measure intelligence. He neither invented the term "intelligence quotient" nor supported its numerical expression. He stated: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :The scale, properly speaking, does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured. (Binet 1905) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Binet had designed the Binet-Simon intelligence scale in order to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. He argued that with proper remedial education programs, most students regardless of background could catch up and perform quite well in school. He did not believe that intelligence was a measurable fixed entity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Binet cautioned: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Some recent thinkers seem to have given their moral support to these deplorable verdicts by affirming that an individual's intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity that cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism; we must try to demonstrate that it is founded on nothing.<ref>Rawat, R. [http://www.rso.cornell.edu/scitech/archive/95sum/bell.html The Return of Determinism?]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Mismeasure of Man=== | ||

| + | Some scientists dispute [[psychometrics]] entirely. In ''[[The Mismeasure of Man]]'' professor [[Stephen Jay Gould]] argued that intelligence tests were based on faulty assumptions and showed their history of being used as the basis for [[scientific racism]]. He wrote: | ||

| + | :…the abstraction of intelligence as a single entity, its location within the brain, its quantification as one number for each individual, and the use of these numbers to rank people in a single series of worthiness, invariably to find that oppressed and disadvantaged groups—races, classes, or sexes—are innately inferior and deserve their status. (pp. 24–25) | ||

| − | + | He spent much of the book criticizing the concept of IQ, including a historical discussion of how the IQ tests were created and a technical discussion of why ''g'' is simply a mathematical artifact. Later editions of the book included criticism of ''[[The Bell Curve]]''. | |

| − | + | Gould does not dispute the stability of test scores, nor the fact that they predict certain forms of achievement. He does argue, however, that to base a concept of intelligence on these test scores alone is to ignore many important aspects of mental ability. | |

| − | + | === Relation between IQ and intelligence === | |

| + | {{see also|Intelligence}} | ||

| + | Several other ways of measuring intelligence have been proposed. [[Daniel Schacter]], [[Daniel Gilbert]], and others have moved beyond general intelligence and IQ as the sole means to describe intelligence.<ref>''[http://select.nytimes.com/2007/09/14/opinion/14brooks.html The Waning of I.Q.]'' by [[David Brooks]], [[The New York Times]]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Test bias === | ||

| + | {{Seealso|Stereotype threat}} | ||

| + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> states that that IQ tests as predictors of social achievement are not biased against people of African descent since they predict future performance, such as school achievement, similarly to the way they predict future performance for European descent.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, IQ tests may well be biased when used in other situations. A 2005 study finds some evidence that the WAIS-R is not culture-fair for Mexican Americans.<ref>[http://asm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/12/3/303 Culture-Fair Cognitive Ability Assessment] Steven P. Verney Assessment, Vol. 12, No. 3, 303-319 (2005)</ref> Other recent studies have questioned the culture-fairness of IQ tests when used in South Africa.<ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15742541&dopt=Abstract Cross-cultural effects on IQ test performance: a review and preliminary normative indications on WAIS-III test performance.] Shuttleworth-Edwards AB, Kemp RD, Rust AL, Muirhead JG, Hartman NP, Radloff SE. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004 Oct;26(7):903-20.</ref><ref>[http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00346.x Case for Non-Biased Intelligence Testing Against Black Africans Has Not Been Made: A Comment on Rushton, Skuy, and Bons (2004)] 1*, Leah K. Hamilton1, Betty R. Onyura1 and Andrew S. Winston International Journal of Selection and Assessment Volume 14 Issue 3 Page 278 - September 2006</ref> Standard intelligence tests, such as the Stanford-Binet, are often inappropriate for children with [[autism]]; the alternative of using developmental or adaptive skills measures are relatively poor measures of intelligence in autistic children, and have resulted in incorrect claims that a majority of children with autism are mentally retarded.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Edelson, MG |date=2006 |title= Are the majority of children with autism mentally retarded? a systematic evaluation of the data |journal= Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl |volume=21 |issue=2 |pages=66–83 |url=http://www.willamette.edu/dept/comm/reprint/edelson/ |accessdate=2007-04-15}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Outdated methodology=== | ||

| + | A 2006 paper argues that mainstream contemporary test analysis does not reflect substantial recent developments in the field and "bears an uncanny resemblance to the psychometric state of the art as it existed in the 1950s."<ref>[http://users.fmg.uva.nl/dborsboom/papers.htm The attack of the psychometricians]. Denny Borsboom. Psychometrika Vol. 71, No. 3, 425–440. September 2006.</ref>It also claims that some of the most influential recent studies on group differences in intelligence, in order to show that the tests are unbiased, use outdated methodology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === The view of the American Psychological Association === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In response to the controversy surrounding ''[[The Bell Curve]]'', the [[American Psychological Association]]'s Board of Scientific Affairs established a task force in 1995 to write a consensus statement on the state of intelligence research which could be used by all sides as a basis for discussion. The [http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/research/Correlation/Intelligence.pdf full text] of the report is available through several websites.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this paper the representatives of the association regret that IQ-related works are frequently written with a view to their political consequences: "research findings were often assessed not so much on their merits or their scientific standing as on their supposed political implications." | ||

| + | |||

| + | The task force concluded that IQ scores do have high predictive validity for individual differences in school achievement. They confirm the predictive validity of IQ for adult occupational status, even when variables such as education and family background have been statistically controlled. They agree that individual (but specifically not population) differences in intelligence are substantially influenced by genetics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They state there is little evidence to show that childhood diet influences intelligence except in cases of severe malnutrition. They agree that there are no significant differences between the average IQ scores of males and females. The task force agrees that large differences do exist between the average IQ scores of blacks and whites, and that these differences cannot be attributed to biases in test construction. The task force suggests that explanations based on social status and cultural differences are possible, and that environmental factors have raised mean test scores in many populations. Regarding genetic causes, they noted that there is not much direct evidence on this point, but what little there is fails to support the genetic hypothesis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The APA journal that published the statement, ''[[American Psychologist]]'', subsequently published eleven critical responses in January 1997, several of them arguing that the report failed to examine adequately the evidence for partly-genetic explanations. | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | < | + | <references/> |

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 179: | ||

*Gottfredson, L.S. (1998). The general intelligence factor. ''Scientific American Presents,'' 9(4):24–29. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1998generalintelligencefactor.pdf PDF] | *Gottfredson, L.S. (1998). The general intelligence factor. ''Scientific American Presents,'' 9(4):24–29. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1998generalintelligencefactor.pdf PDF] | ||

*Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Suppressing intelligence research: Hurting those we intend to help. In R. H. Wright & N. A. Cummings (Eds.), Destructive trends in mental health: The well-intentioned path to harm (pp. 155–186). New York: Taylor and Francis. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2003suppressingintelligence.pdf Pre-print PDF] [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2005suppressingintelligence.pdf PDF] | *Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Suppressing intelligence research: Hurting those we intend to help. In R. H. Wright & N. A. Cummings (Eds.), Destructive trends in mental health: The well-intentioned path to harm (pp. 155–186). New York: Taylor and Francis. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2003suppressingintelligence.pdf Pre-print PDF] [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2005suppressingintelligence.pdf PDF] | ||

| − | * Gottfredson, L. S. (in press). "Social consequences of group differences in cognitive ability (Consequencias sociais das diferencas de grupo em habilidade cognitiva)" | + | * Gottfredson, L. S. (in press). "Social consequences of group differences in cognitive ability (Consequencias sociais das diferencas de grupo em habilidade cognitiva)." In C. E. Flores-Mendoza & R. Colom (Eds.), ''Introdução à psicologia das diferenças individuals''. Porto Alegre, Brazil: ArtMed Publishers. [http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/2004socialconsequences.pdf PDF] |

*Gray, J.R., C.F. Chabris, and T.S. Braver, Neural mechanisms of general fluid intelligence. Nat Neurosci, 2003. 6(3): p. 316-22. | *Gray, J.R., C.F. Chabris, and T.S. Braver, Neural mechanisms of general fluid intelligence. Nat Neurosci, 2003. 6(3): p. 316-22. | ||

*Gray, J.R. and P.M. Thompson, Neurobiology of intelligence: science and ethics. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2004. 5(6): p. 471-82. | *Gray, J.R. and P.M. Thompson, Neurobiology of intelligence: science and ethics. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2004. 5(6): p. 471-82. | ||

| Line 167: | Line 193: | ||

* Rowe, D. C., W. J. Vesterdal, and J. L. Rodgers, "The Bell Curve Revisited: How Genes and Shared Environment Mediate IQ-SES Associations," University of Arizona, 1997 | * Rowe, D. C., W. J. Vesterdal, and J. L. Rodgers, "The Bell Curve Revisited: How Genes and Shared Environment Mediate IQ-SES Associations," University of Arizona, 1997 | ||

*Schoenemann, P.T., M.J. Sheehan, and L.D. Glotzer, Prefrontal white matter volume is disproportionately larger in humans than in other primates. Nat Neurosci, 2005. | *Schoenemann, P.T., M.J. Sheehan, and L.D. Glotzer, Prefrontal white matter volume is disproportionately larger in humans than in other primates. Nat Neurosci, 2005. | ||

| − | *Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Evans A, Rapoport J, and Giedd J (2006), "Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents" | + | *Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Evans A, Rapoport J, and Giedd J (2006), "Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents." Nature 440, 676-679. |

* Tambs K, Sundet JM, Magnus P, Berg K. "Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance between occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ: a study of twins." Behav Genet. 1989 Mar;19(2):209–22. PMID 2719624. | * Tambs K, Sundet JM, Magnus P, Berg K. "Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance between occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ: a study of twins." Behav Genet. 1989 Mar;19(2):209–22. PMID 2719624. | ||

*Thompson, P.M., Cannon, T.D., Narr, K.L., Van Erp, T., Poutanen, V.-P., Huttunen, M., Lönnqvist, J., Standertskjöld-Nordenstam, C.-G., Kaprio, J., Khaledy, M., Dail, R., Zoumalan, C.I., Toga, A.W. (2001). "Genetic influences on brain structure." Nature Neuroscience 4, 1253-1258. | *Thompson, P.M., Cannon, T.D., Narr, K.L., Van Erp, T., Poutanen, V.-P., Huttunen, M., Lönnqvist, J., Standertskjöld-Nordenstam, C.-G., Kaprio, J., Khaledy, M., Dail, R., Zoumalan, C.I., Toga, A.W. (2001). "Genetic influences on brain structure." Nature Neuroscience 4, 1253-1258. | ||

| Line 175: | Line 201: | ||

* [http://www.psychpage.com/learning/library/intell/mainstream.html The Wall Street Journal: Mainstream Science on Intelligence][http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1997mainstream.pdf PDF Reprint - Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography.] | * [http://www.psychpage.com/learning/library/intell/mainstream.html The Wall Street Journal: Mainstream Science on Intelligence][http://www.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1997mainstream.pdf PDF Reprint - Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography.] | ||

| − | * [[American Psychological Association|APA]] — [http://www.lrainc.com/swtaboo/taboos/apa_01.html Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns] | + | * [[American Psychological Association|APA]]—[http://www.lrainc.com/swtaboo/taboos/apa_01.html Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns] |

* [http://www.apa.org/science/testing_on_the_internet.pdf APA Committee on Online Psychological Tests and Assessment report] | * [http://www.apa.org/science/testing_on_the_internet.pdf APA Committee on Online Psychological Tests and Assessment report] | ||

| Line 185: | Line 211: | ||

===IQ testing=== | ===IQ testing=== | ||

| − | * "[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/30/science/30brain.html Scans Show Different Growth for Intelligent Brains]" | + | * "[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/30/science/30brain.html Scans Show Different Growth for Intelligent Brains]," ''New York Times'', March 30, 2006 |

* [http://members.shaw.ca/delajara/ IQ comparison site] | * [http://members.shaw.ca/delajara/ IQ comparison site] | ||

* [http://www.iqsociety.org/general/IQchart.pdf IQ comparison chart] | * [http://www.iqsociety.org/general/IQchart.pdf IQ comparison chart] | ||

| Line 198: | Line 224: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Intelligence_quotient|176000780}} |

Revision as of 21:59, 5 December 2007

An intelligence quotient or IQ is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtests scores. Regardless of design, all IQ tests measure the same general intelligence factor also referred to as "g." Component tests are generally designed and chosen because they are found to be predictable of later intellectual development. In some studies, IQ has been shown to correlate with job performance, socioeconomic advancement, and other "social pathologies." Recent work has demonstrated links between IQ and health, longevity, and functional literacy. However, IQ tests have engendered much controversy and it is important to note that they do not measure all meanings of "intelligence." IQ scores are relative. Meaning, that the placement of an IQ score is similar to a placement in a race as they are both dependent upon the performance of the other participants.

History

In 1905, the French psychologist Alfred Binet published the first modern test of intelligence. His principal goal was to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. Along with his collaborator Theodore Simon, Binet published revisions of his Binet-Simon intelligence scale in 1908 and 1911, the last appearing just before his untimely death. In 1912, the abbreviation of "intelligence quotient" or IQ, a translation of the German Intelligenz-quotient, was coined by the German psychologist William Stern.

A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by Lewis M. Terman, from Stanford University, who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient (IQ). Terman's test, which he named the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale formed the basis for one of the modern intelligence tests still commonly used today.

Originally, IQ was calculated as a ratio with the formula

A 10-year-old who scored as high as the average 13-year-old, for example, would have an IQ of 130 (100*13/10).

In 1939 David Wechsler published the first intelligence test explicitly designed for an adult population, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, or WAIS. Since publication of the WAIS, Wechsler extended his scale downward to create the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, or WISC. The third edition of the WAIS (WAIS-III) is the most widely used psychological test in the world, and the fourth edition of the WISC (WISC-IV) is the most widely used intelligence test for children. The Wechsler scales contained separate subscores for verbal and performance IQ, thus being less dependent on overall verbal ability than early versions of the Stanford-Binet scale, and was the first intelligence scale to base scores on a standardized normal distribution rather than an age-based quotient.

Since the publication of the WAIS, almost all intelligence scales have adopted the normal distribution method of scoring. The use of the normal distribution scoring method makes the term "intelligence quotient" an inaccurate description of the intelligence measurement, but "IQ" still enjoys colloquial usage, and is used to describe all of the intelligence scales currently in use.

IQ testing

Structure

IQ tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question, while others use several different subtests. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores.

A typical IQ test requires the test subject to solve a fair number of problems in a set time under supervision. Most IQ tests include items from various domains, such as short-term memory, verbal knowledge, spatial visualization, and perceptual speed. Some tests have a total time limit, others have a time limit for each group of problems, and there are a few untimed, unsupervised tests, typically geared to measuring high intelligence. The widely used standardized test for determining IQ, the WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III), consists of fourteen subtests, seven verbal (Information, Comprehension, Arithmetic, Similarities, Vocabulary, Digit Span, and Letter-Number Sequencing) and seven performance (Digit Symbol-Coding, Picture Completion, Block Design, Matrix Reasoning, Picture Arrangement, Symbol Search, and Object Assembly).

Scoring

When standardizing an IQ test, a representative sample of the population is tested using each test question. IQ tests are calibrated in such a way as to yield a normal distribution, or "bell curve." Each IQ test, however, is designed and valid only for a certain IQ range. Because so few people score in the extreme ranges, IQ tests usually cannot accurately measure very low and very high IQs.

Various IQ tests measure a standard deviation with a different number of points. Thus, when an IQ score is stated, the standard deviation used should also be stated.

When an individual has scores that do not correlate with each other, there is a good reason to suspect a learning disability or other cause for this lack of correlation. Tests have been chosen for inclusion because they display the ability to use this method to predict later difficulties in learning.

An individual's IQ score may or may not be stable over the course of the individual's lifetime.[1]

IQ and general intelligence factor

Modern IQ tests produce scores for different areas (e.g., language fluency, three-dimensional thinking), with the summary score calculated from subtest scores. The average score, according to the bell curve, is 100. Individual subtest scores tend to correlate with one another, even when seemingly disparate in content.

Mathematical analysis of individuals' scores on the subtests of a single IQ test or the scores from a variety of different IQ tests (e.g., Stanford-Binet, WISC-R, Raven's Progressive Matrices, Cattell Culture Fair III, Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test, Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, and others) find that they can be described mathematically as measuring a single common factor and various factors that are specific to each test. This kind of factor analysis has led to the theory that underlying these disparate cognitive tasks is a single factor, termed the general intelligence factor (or g), that corresponds with the common-sense concept of intelligence.[2] In the normal population, g and IQ are roughly 90% correlated and are often used interchangeably.

Tests differ in their g-loading, which is the degree to which the test score reflects g rather than a specific skill or "group factor" (such as verbal ability, spatial visualization, or mathematical reasoning).

Mental handicaps

Individuals with an unusually low IQ score, varying from about 70 ("Educable Mentally Retarded") to as low as 20 (usually caused by a neurological condition), are considered to have developmental difficulties. However, there is no true IQ-based classification for developmental disabilities.

Practical validity

Evidence for the practical validity of IQ has been suggested through the examination of the correlation between IQ scores and economic and social indicators of valued life outcomes.

Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between g and life outcomes are pervasive, despite the fact that IQ and happiness are not correlates. IQ and g correlate highly with school performance and job performance, moderately with income, and to a small degree whether or not the individual will abide by the law.

General intelligence whhich in the literature is typically called "cognitive ability" is the best predictor of job performance by the standard measure of validity. Validity is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure), and ranges between −1.0 (the score is perfectly wrong in predicting outcome) and 1.0 (the score perfectly predicts the outcome). The validity of cognitive ability for job performance tends to increase with job complexity and varies across different studies, ranging from 0.2 for unskilled jobs to 0.8 for the most complex jobs.

A meta-analysis (Hunter and Hunter, 1984) which pooled validity results across many studies encompassing thousands of workers (32,124 for cognitive ability), reports that the validity of cognitive ability for entry-level jobs is 0.54, larger than any other measure including job tryout (0.44), experience (0.18), interview (0.14), age (−0.01), education (0.10), and biographical inventory (0.37).

Because higher test validity allows more accurate prediction of job performance, companies have a strong incentive to use cognitive ability tests to select and promote employees. IQ thus has high practical validity in economic terms. The utility of using one measure over another is proportional to the difference in their validities, all else equal. This is one economic reason why companies use job interviews (validity 0.14) rather than randomly selecting employees (validity 0.0).

However, the US Civil Rights Act, stemming from the 1971 United States Supreme Court decision Griggs v. Duke Power Co., have prevented American employers from using cognitive ability tests as a controlling factor in selecting employees where (1) the use of the test would have a disparate impact on hiring by race and (2) where the test is not shown to be directly relevant to the job at issue. Instead, where there is no direct relevance to the job or class of jobs at issue, tests have only been legally permitted to be used in conjunction with a subjective appraisal process. The U.S. military uses the Armed Forces Qualifying Test (AFQT), as higher scores correlate with significant increases in effectiveness of both individual soldiers and units.[1] [2] Microsoft is known for using non-illegal tests that correlate with IQ tests as part of the interview process, weighing the results even more than experience in many cases.[3] [4]

Some researchers have echoed the popular claim that "in economic terms it appears that the IQ score measures something with decreasing marginal value. It is important to have enough of it, but having lots and lots does not buy you that much." (Detterman and Daniel, 1989)[5]

However, some studies suggest IQ continues to confer large benefits at very high levels. Ability and performance for jobs are linearly related, such that at all IQ levels, an increase in IQ translates into a concomitant increase in performance (Coward and Sackett, 1990). In an analysis of hundreds of siblings, it was found that IQ has a substantial effect on income independently of family background (Murray, 1998).

Other studies question the real-world importance of whatever is measured with IQ tests, especially for differences in accumulated wealth and general economic inequality in a nation. IQ correlates highly with school performance but the correlations decrease the closer one gets to real-world outcomes, like with job performance, and still lower with income. It explains less than one sixth of the income variance [6]. Even for school grades, other factors explain most the variance. One study found that, controlling for IQ across the entire population, 90 to 95 percent of economic inequality would continue to exist. [7]. Another recent study (2002) found that wealth, race, and schooling are important to the inheritance of economic status, but IQ is not a major contributor and the genetic transmission of IQ is even less important [8]. Some argue that IQ scores are used as an excuse for not trying to reduce poverty or otherwise improve living standards for all. Claims of low intelligence has historically been used to justify the feudal system and unequal treatment of women, nowadays, many studies find identical average IQs among men and women. In contrast, others claim that the refusal of high-IQ elites to take IQ seriously as a cause of inequality is itself immoral.[9]

Genetics versus environment

The role of genes and environment (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ is reviewed in Plomin et al. (2001, 2003). The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called heritability. Heritability scores range from 0 to 1, and can be interpreted as the percentage of variation (e.g. in IQ) that is due to variation in genes. Twin and adoption studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait. Until recently heritability was mostly studied in children. These studies find the heritability of IQ is approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. A heritability of 0.5 implies that IQ is "substantially" heritable. Studies with adults show that they have a higher heritability of IQ than children do and that heritability could be as high as 0.8. The American Psychological Association's 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the White population the heritability of IQ is "around .75" (p. 85).[10]

Environment

Environmental factors play a large role in determining IQ in certain situations. Proper childhood nutrition appears to be critical for cognitive development as malnutrition correlates to lower IQ. Other research indicates environmental factors such as prenatal exposure to toxins, the duration of breastfeeding, and micronutrient deficiency affecting IQ.

Nearly all personality traits show that, contrary to expectations, environmental effects actually cause adoptive siblings raised in the same family to be as different as children who were raised in different families (Harris, 1998; Plomin & Daniels, 1987). IQ is an exception among children. The IQs of adoptive siblings, who share no genetic relation but do share a common family environment, are correlated at .32. Despite attempts to isolate the factors that cause adoptive siblings to be similar, they have not been identified. It is important to note, however, that shared family effects on IQ disappear after adolescence.

Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture," is observed for IQ. This phenomenon is measured similarly to heritability; but instead of measuring variation in IQ due to genes, variation in environment due to genes is determined. One study found that 40% of variation in measures of home environment are accounted for by genetic variation. This suggests that the way human beings craft their environment is due in part to genetic influences.

A study of French children adopted between the ages of 4 and 6 shows the continuing interplay of nature and nurture. The children came from poor backgrounds with I.Q.’s that averaged 77, putting them near retardation. Nine years later after adoption, they retook the I.Q. tests, and all of them did better. The amount they improved was directly related to the adopting family’s status. "Children adopted by farmers and laborers had average I.Q. scores of 85.5; those placed with middle-class families had average scores of 92. The average I.Q. scores of youngsters placed in well-to-do homes climbed more than 20 points, to 98."[11] This study suggests that IQ is not stable over the course of ones lifetime and that, even in later childhood, a change in individual's environment can have a significant effect on IQ.

Genetics

It is reasonable to expect that genetic influences on traits like IQ should become less important as one gains experiences with age. Surprisingly, the opposite occurs. Heritability measures in infancy are as low as 20%, around 40% in middle childhood, and as high as 80% in adulthood.[3]

Shared family effects also seem to disappear by adulthood. Adoption studies show that, after adolescence, adopted siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monzygotic or identical twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than fraternal or dizygotic twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adopted siblings (~0.0).[4]

IQ correlations

Race and IQ

While IQ scores of individual members of different racial or ethnic groups are distributed across the IQ scale, groups vary in where their members cluster along the IQ scale. Ashkenazi Jews and East Asians cluster higher than Whites, while Hispanics and Sub-Saharan Africans cluster lower.[5] Much research has been devoted to the extent and potential causes of racial-ethnic group differences in IQ, and the underlying purposes and validity of the tests has been examined. Most experts conclude that examination of many types of test bias and simple differences in socioeconomic status have failed to explain the IQ clustering differences.[6]

The findings in this field are often thought to conflict with fundamental social philosophies and have engendered much large controversy.[7]

Religiosity and IQ

Several studies have investigated the relationship between intelligence and the degree of religious belief (excluding humanist faith), with most showing that intelligence averages decrease significantly with the "importance of religion" as self-reporters by the testee. Many studies illustrate the same results despite when and where they were conducted. Charles Murray, author of the infamous The Bell Curve, chronicled the attitudes and beliefs of the Elites (those who have a high IQ) in regards to religion spanning from Ancient times to the Modern Day and across the globe in another book entitled Human Accomplishment. He wrote that Elites in the First World, post-1950 era were more hostile in their attitudes toward religion.

Health and IQ

Persons with a higher IQ have generally lower adult morbidity and mortality. This may be because they are more adept at avoiding injury and take better care of their own health, or it may be due to a slight increased propensity for material wealth (see above). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, severe clinical depression, and schizophrenia are less prevalent in those with higher IQ as these disorders greatly affect participant's concentration. Despite this, however, higher IQ shows a higher prevalence of those suffering from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder [12].

Research in Scotland has shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long [13].

Criticism and views

Binet

Alfred Binet did not believe that IQ test scales qualified to measure intelligence. He neither invented the term "intelligence quotient" nor supported its numerical expression. He stated:

- The scale, properly speaking, does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured. (Binet 1905)

Binet had designed the Binet-Simon intelligence scale in order to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. He argued that with proper remedial education programs, most students regardless of background could catch up and perform quite well in school. He did not believe that intelligence was a measurable fixed entity.

Binet cautioned:

- Some recent thinkers seem to have given their moral support to these deplorable verdicts by affirming that an individual's intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity that cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism; we must try to demonstrate that it is founded on nothing.[8]

The Mismeasure of Man

Some scientists dispute psychometrics entirely. In The Mismeasure of Man professor Stephen Jay Gould argued that intelligence tests were based on faulty assumptions and showed their history of being used as the basis for scientific racism. He wrote:

- …the abstraction of intelligence as a single entity, its location within the brain, its quantification as one number for each individual, and the use of these numbers to rank people in a single series of worthiness, invariably to find that oppressed and disadvantaged groups—races, classes, or sexes—are innately inferior and deserve their status. (pp. 24–25)

He spent much of the book criticizing the concept of IQ, including a historical discussion of how the IQ tests were created and a technical discussion of why g is simply a mathematical artifact. Later editions of the book included criticism of The Bell Curve.

Gould does not dispute the stability of test scores, nor the fact that they predict certain forms of achievement. He does argue, however, that to base a concept of intelligence on these test scores alone is to ignore many important aspects of mental ability.

Relation between IQ and intelligence

- See also: Intelligence

Several other ways of measuring intelligence have been proposed. Daniel Schacter, Daniel Gilbert, and others have moved beyond general intelligence and IQ as the sole means to describe intelligence.[9]

Test bias

The American Psychological Association's report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995)[1] states that that IQ tests as predictors of social achievement are not biased against people of African descent since they predict future performance, such as school achievement, similarly to the way they predict future performance for European descent.[1]

However, IQ tests may well be biased when used in other situations. A 2005 study finds some evidence that the WAIS-R is not culture-fair for Mexican Americans.[10] Other recent studies have questioned the culture-fairness of IQ tests when used in South Africa.[11][12] Standard intelligence tests, such as the Stanford-Binet, are often inappropriate for children with autism; the alternative of using developmental or adaptive skills measures are relatively poor measures of intelligence in autistic children, and have resulted in incorrect claims that a majority of children with autism are mentally retarded.[13]

Outdated methodology

A 2006 paper argues that mainstream contemporary test analysis does not reflect substantial recent developments in the field and "bears an uncanny resemblance to the psychometric state of the art as it existed in the 1950s."[14]It also claims that some of the most influential recent studies on group differences in intelligence, in order to show that the tests are unbiased, use outdated methodology.

The view of the American Psychological Association

In response to the controversy surrounding The Bell Curve, the American Psychological Association's Board of Scientific Affairs established a task force in 1995 to write a consensus statement on the state of intelligence research which could be used by all sides as a basis for discussion. The full text of the report is available through several websites.[1]

In this paper the representatives of the association regret that IQ-related works are frequently written with a view to their political consequences: "research findings were often assessed not so much on their merits or their scientific standing as on their supposed political implications."

The task force concluded that IQ scores do have high predictive validity for individual differences in school achievement. They confirm the predictive validity of IQ for adult occupational status, even when variables such as education and family background have been statistically controlled. They agree that individual (but specifically not population) differences in intelligence are substantially influenced by genetics.

They state there is little evidence to show that childhood diet influences intelligence except in cases of severe malnutrition. They agree that there are no significant differences between the average IQ scores of males and females. The task force agrees that large differences do exist between the average IQ scores of blacks and whites, and that these differences cannot be attributed to biases in test construction. The task force suggests that explanations based on social status and cultural differences are possible, and that environmental factors have raised mean test scores in many populations. Regarding genetic causes, they noted that there is not much direct evidence on this point, but what little there is fails to support the genetic hypothesis.

The APA journal that published the statement, American Psychologist, subsequently published eleven critical responses in January 1997, several of them arguing that the report failed to examine adequately the evidence for partly-genetic explanations.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Neisser et al. (August 7, 1995). Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns. Board of Scientific Affairs of the American Psychological Association. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- ↑ Linda S. Gottfredson (1998-11). The General Intelligence Factor. Scientific American. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- ↑ Plomin et al. (2001, 2003)

- ↑ Plomin et al. (2001, 2003)

- ↑ Gottfredson et al. 1994 (ctrl+f "groups")

- ↑ Neisser et al. 1995

- ↑ The controversy itself has caused some scientists to debate whether such areas of science are inappropriate, or whether group differences in traits are just another area of the science of human nature. (See Race and intelligence#Utility of research and racism.)

- ↑ Rawat, R. The Return of Determinism?

- ↑ The Waning of I.Q. by David Brooks, The New York Times

- ↑ Culture-Fair Cognitive Ability Assessment Steven P. Verney Assessment, Vol. 12, No. 3, 303-319 (2005)

- ↑ Cross-cultural effects on IQ test performance: a review and preliminary normative indications on WAIS-III test performance. Shuttleworth-Edwards AB, Kemp RD, Rust AL, Muirhead JG, Hartman NP, Radloff SE. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004 Oct;26(7):903-20.

- ↑ Case for Non-Biased Intelligence Testing Against Black Africans Has Not Been Made: A Comment on Rushton, Skuy, and Bons (2004) 1*, Leah K. Hamilton1, Betty R. Onyura1 and Andrew S. Winston International Journal of Selection and Assessment Volume 14 Issue 3 Page 278 - September 2006

- ↑ Edelson, MG (2006). Are the majority of children with autism mentally retarded? a systematic evaluation of the data. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 21 (2): 66–83.

- ↑ The attack of the psychometricians. Denny Borsboom. Psychometrika Vol. 71, No. 3, 425–440. September 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carroll, J.B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytical studies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Coward, W.M. and Sackett, P.R. (1990). Linearity of ability-performance relationships: A reconfirmation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75:297–300.

- Duncan, J., P. Burgess, and H. Emslie (1995) Fluid intelligence after frontal lobe lesions. Neuropsychologia, 33(3): p. 261-8.

- Duncan, J., et al., A neural basis for general intelligence. Science, 2000. 289(5478): p. 457-60.

- Frey, M.C. and Detterman, D.K. (2003) Scholastic Assessment or g? The Relationship Between the Scholastic Assessment Test and General Cognitive Ability. Psychological Science, 15(6):373–378. PDF

- Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). "Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life." Intelligence, 24(1), 79–132. PDF

- Gottfredson, L.S. (1998). The general intelligence factor. Scientific American Presents, 9(4):24–29. PDF

- Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Suppressing intelligence research: Hurting those we intend to help. In R. H. Wright & N. A. Cummings (Eds.), Destructive trends in mental health: The well-intentioned path to harm (pp. 155–186). New York: Taylor and Francis. Pre-print PDF PDF

- Gottfredson, L. S. (in press). "Social consequences of group differences in cognitive ability (Consequencias sociais das diferencas de grupo em habilidade cognitiva)." In C. E. Flores-Mendoza & R. Colom (Eds.), Introdução à psicologia das diferenças individuals. Porto Alegre, Brazil: ArtMed Publishers. PDF

- Gray, J.R., C.F. Chabris, and T.S. Braver, Neural mechanisms of general fluid intelligence. Nat Neurosci, 2003. 6(3): p. 316-22.

- Gray, J.R. and P.M. Thompson, Neurobiology of intelligence: science and ethics. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2004. 5(6): p. 471-82.

- Haier RJ, Jung RE, Yeo RA, et al. (2005). The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: sex matters. NeuroImage 25: 320–327.

- Harris, J. R. (1998). The nurture assumption : why children turn out the way they do. New York, Free Press.

- Hunt, E. (2001). Multiple views of multiple intelligence. [Review of Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century.]

- Jensen, A.R. (2006). "Clocking the Mind: Mental Chronometry and Individual Differences." Elsevier Science. --->New release scheduled for early June, 2006.

- McClearn, G. E., Johansson, B., Berg, S., Pedersen, N. L., Ahern, F., Petrill, S. A., & Plomin, R. (1997). Substantial genetic influence on cognitive abilities in twins 80 or more years old. Science, 276, 1560–1563.

- Murray, Charles (1998). Income Inequality and IQ, AEI Press PDF

- Noguera, P.A. (2001). Racial politics and the elusive quest for excellence and equity in education. In Motion Magazine article

- Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Craig, I. W., & McGuffin, P. (2003). Behavioral genetics in the postgenomic era. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., McClearn, G. E., & McGuffin, P. (2001). Behavioral genetics (4th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

- Rowe, D. C., W. J. Vesterdal, and J. L. Rodgers, "The Bell Curve Revisited: How Genes and Shared Environment Mediate IQ-SES Associations," University of Arizona, 1997

- Schoenemann, P.T., M.J. Sheehan, and L.D. Glotzer, Prefrontal white matter volume is disproportionately larger in humans than in other primates. Nat Neurosci, 2005.

- Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Evans A, Rapoport J, and Giedd J (2006), "Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents." Nature 440, 676-679.

- Tambs K, Sundet JM, Magnus P, Berg K. "Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance between occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ: a study of twins." Behav Genet. 1989 Mar;19(2):209–22. PMID 2719624.

- Thompson, P.M., Cannon, T.D., Narr, K.L., Van Erp, T., Poutanen, V.-P., Huttunen, M., Lönnqvist, J., Standertskjöld-Nordenstam, C.-G., Kaprio, J., Khaledy, M., Dail, R., Zoumalan, C.I., Toga, A.W. (2001). "Genetic influences on brain structure." Nature Neuroscience 4, 1253-1258.

External links

Collective statements

- The Wall Street Journal: Mainstream Science on IntelligencePDF Reprint - Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography.

- APA—Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns

- APA Committee on Online Psychological Tests and Assessment report

Review papers

- Scientific American: The General Intelligence Factor

- Scientific American: Intelligence Considered

- Neurobiology of Intelligence: Science and Ethics PDF

IQ testing

- "Scans Show Different Growth for Intelligent Brains," New York Times, March 30, 2006

- IQ comparison site

- IQ comparison chart

- Estimated IQs of the greatest geniuses (note: these sorts of estimates are considered highly suspect; the psychological community generally regards it impossible to infer an "IQ" from writing samples or accomplishments)

Online IQ tests

- Kids IQ Test Center Free information regarding childrens intelligence.

- Online IQ Test An online IQ test (40 questions, ~ 40 minutes)

- Online Intelligence Testing IQ Test (clever method of disabusing notions about online IQ tests)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.