Difference between revisions of "Hieroglyph" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

{{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | ||

[[Image:Troy VIIb hieroglyphic seal reverse.png|thumb|160px|Drawing of the hieroglyphic seal found in the [[Troy VIIb]] layer.]] | [[Image:Troy VIIb hieroglyphic seal reverse.png|thumb|160px|Drawing of the hieroglyphic seal found in the [[Troy VIIb]] layer.]] | ||

| − | '''Anatolian hieroglyphs''' were used in [[Anatolia]], as well as parts of modern [[Syria]] during the second and third millennia B.C.E. They were once commonly known as [[Hittite]] hieroglyphs, as one of the first discovered uses of the script was on personal seals from the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusha. The language represented is [[Luwian]] (sometimes spelled “Luvian”,) not [[Hittite language|Hittite]], and the term '''Luwian hieroglyphs''' is often used in English publications. It is possible that the | + | '''Anatolian hieroglyphs''' were used in [[Anatolia]], as well as parts of modern [[Syria]] during the second and third millennia B.C.E. They were once commonly known as [[Hittite]] hieroglyphs, as one of the first discovered uses of the script was on personal seals from the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusha. The language represented is [[Luwian]] (sometimes spelled “Luvian”,) not [[Hittite language|Hittite]], and the term '''Luwian hieroglyphs''' is often used in English publications. It is possible that the hieroglyphs used on Hittite personal seals were used in a symbolic nature and were not intended to represent language, but rather concepts such as names, titles, or good luck symbols.<ref>Daniels, Peter T. and William Bright, [http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/hluvianscript.pdf The World’s Writing Systems,] Oxford University Press, p.120, 1996. Retrieved January 14, 2009.</ref> |

| − | The Anatolian hieroglyphs utilize both logographic and phonographic elements, as well as the use of logographic elements that have a phonetic compliment. Most of the signs are pictoral in nature, representing human figures, plants, animals, and everyday objects. Text is most commonly arranged horizontally, beginning in a top corner and working its way down the page in alternating left-to-right/right-to-left registers. This practice was called by the [[Ancient Greek|Greeks]] | + | The Anatolian hieroglyphs utilize both logographic and phonographic elements, as well as the use of logographic elements that have a phonetic compliment. Most of the signs are pictoral in nature, representing human figures, plants, animals, and everyday objects. Text is most commonly arranged horizontally, beginning in a top corner and working its way down the page in alternating left-to-right/right-to-left registers. This practice was called ''[[boustrophedon]]'' by the [[Ancient Greek|Greeks]], meaning "as the ox turns" (as when plowing a field). Within each register, signs are arranged vertically in columns. There are no word breaks, although a word divider sign is sometimes found.<ref>Daniels, Peter T. and William Bright, [http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/hluvianscript.pdf The World’s Writing Systems,] Oxford University Press, pp.121-3, 1996. Retrieved January 14, 2009.</ref> |

Revision as of 16:17, 16 January 2009

A hieroglyph is a character used in a system of pictoral writing, and derives from the Greek term for “sacred carving,” translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words.” The term originally referred only to the Egyptian hieroglyphs, but was later also applied to ancient Cretan, Luwian, Mayan and Mi'kmaq scripts. There is no connection between Egyptian hieroglyphs and other hieroflyphic scripts; all evolved independently of one another. [1]

Etymology

The word Hieroglyphs derives from the Greek words ἱερός (hierós 'sacred') and γλύφειν (glúphein 'to carve' or 'to write', see glyph. This was translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words,” a phrase derived from the Egyptian practice of using hieroglyphic writing predominantly for religious or sacred purposes.

The term “hieroglyphics,” used as a noun, was once common, but now denotes more informal usage. In academic circles, the term “hieroglyphs” has replaced “hieroglyphic” to refer to both the language as a whole and the individual characters that compose it. “Hieroglyphic” is still used as an adjective (e.g., a hieroglyphic writing system).

Major Hieroglyphic Writing Systems

Egyptian hieroglyphs

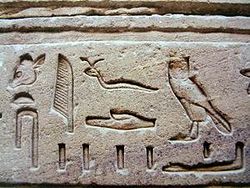

Egyptian hieroglyphs are perhaps the most well-known hieroglyphic writing system, and the one from which the term “hieroglyphic” originated. This formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians consists of a combination of phonetic signs, ideograms, and determinatives. Phonetic signs work like letters of an alphabet: a single sign stands for a letter (or combination of letters.) Ideograms are made from signs that are accompanied by a vertical line, which indicates that the sign stands for the object it represents. Determinatives appear, when needed, at the end of a word, and give a clue as to the meaning of a word.[2]

Egyptian hieroglyphs were used mainly for formal inscriptions (hence their name, which translates to “the god’s words”.) Everyday writing, such as record keeping or letter writing, used the Hieratic script, a simplified version of hieroglyphic writing. Hieratic script is structurally the same as hieroglyphic writing, but people, animals, and objects are no longer recognizable.

One of the oldest and most famous examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs can be found on the Narmer Palette, a shield shaped palette that dates to around 3200 B.C.E. The palette was discovered in 1898 by archaeologist James Quibell in the ancient city of Nekhen (currently Hierakonpolis), believed to be the Pre-Dynastic capital of Upper Egypt. The palette is believed to be a gift offering from King Narmer to the god Amun-Ra. Narmer’s name is written at the top on both the front and back of the palette.[3]

Egyptian hieroglyphic writing used a core of about 800 hieroglyphs. This number varied; during the Greco-Roman period, more than 5,000 hieroglyphs were in use.[4] Interestingly enough, hieroglyphic writing did not incorporate vowel sounds.

Dongba script

The Dongba, Tomba or Tompa script is a pictographic writing system used by the priests of the Naxi people, an ethnic minority found mainly near the Yangtze River in China, as well as Tibet. The Dongba script is unique in that it is the only living pictographic language in the world; Naxi priests still use the Dongba script to create manuscripts for ceremonies like funerals and blessings.[5]

The origin of the Dongba script is a matter of legend and debate. It is likely that the script has been in use for close to one thousand years, and was widely used by the tenth century. Both the Naxi language and script were suppressed after the Communist victory and during China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960’s, but efforts have been made to revive interest in the language.

The Dongba script consists of about 1,400 symbols. Ninety percent of these are pictograms, although some are used to represent phonetic values. The Naxi language is also written using Geba (a script more similar to Chinese character writing) or a Latin alphabet writing system based on Pinyin.[6]

|

|

Mayan hieroglyphs

The Mayan script, also known as Mayan hieroglyphs, was the writing system of the pre-Columbian Mayan civilization of Mesoamerica, and consisted of a highly elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls or bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, or molded in stucco. While the earliest known Mayan script is dated around 250 B.C.E., the script may have been developed much earlier. The Mayan civilization itself may have developed as early as 3,000 B.C.E. The Yucatec Maya used the script up until the sixteenth century.

The Mayan script is made up of about 550 logograms (representing whole words,) and 150 syllabograms (representing syllables,) as well as glyphs for the names of places and gods. For much of modern history, it was commonly believed that the Mayan script was not a complete writing system, and did not actually represent a language. In the 1950’s, Russian ethnologist Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov correctly suggested the script was partly phonetic and represented the Yucatec Mayan language. Today, most Mayan texts can be interpreted.[7]

Cretan hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs were discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who is perhaps most well known for his excavations of the palace he named Knossos at Crete, as well as the discovery of the Minoan civilization that inhabited it.

Cretan hieroglyphs are the first of three scripts discovered at Knossos, and are thought to date around 2000 B.C.E. The script was found on Bronze Age clay tablets and sealstones at Knossos, as well as artifacts from the Minoan Palace at Petras in eastern Crete.

Later scripts, known as Linear A and Linear B, may have evolved from these hieroglyphs. Linear A is thought to date to 1850-1700 B.C.E.; the original pictograms present in the hieroglyphic script have been reduced to a more linear form.[8]

The Cretan hieroglyphic script contains over one hundred pictograms, including representations of a lyre, carpenter’s tools, dog heads, and bees.[9]

Anatolian hieroglyphs

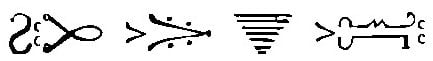

Anatolian hieroglyphs were used in Anatolia, as well as parts of modern Syria during the second and third millennia B.C.E. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, as one of the first discovered uses of the script was on personal seals from the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusha. The language represented is Luwian (sometimes spelled “Luvian”,) not Hittite, and the term Luwian hieroglyphs is often used in English publications. It is possible that the hieroglyphs used on Hittite personal seals were used in a symbolic nature and were not intended to represent language, but rather concepts such as names, titles, or good luck symbols.[10]

The Anatolian hieroglyphs utilize both logographic and phonographic elements, as well as the use of logographic elements that have a phonetic compliment. Most of the signs are pictoral in nature, representing human figures, plants, animals, and everyday objects. Text is most commonly arranged horizontally, beginning in a top corner and working its way down the page in alternating left-to-right/right-to-left registers. This practice was called boustrophedon by the Greeks, meaning "as the ox turns" (as when plowing a field). Within each register, signs are arranged vertically in columns. There are no word breaks, although a word divider sign is sometimes found.[11]

Olmec hieroglyphs

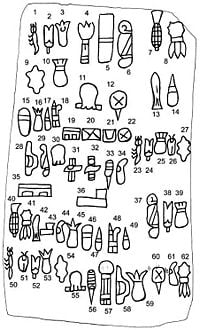

The Olmec civilization was one of the first complex societies in early Mesoamerica, dating from 1500 B.C.E. through 100 B.C.E., and possibly even later. Although it was known that Olmec culture was full of accomplishments in art, mathematics, and engineering, including drainage systems and accurate calendars, it was not until the Cascajal Block was discovered in 1999 that there was any evidence of a true Olmec writing system.

The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in a pile of debris near Veracruz lowlands in the ancient Olmec heartland. The slab of rock is carved with sixty-two signs and dates to the early first millennium B.C.E. The block weighs approximately 26 pounds, and is 36 centimeters by 21 centimeters. The nature of the signs, their sequencing patterns, and consistent reading order are all indications that the tablet is an example of a Olmec writing system. Interestingly enough, the side of the Cascajal Block that contains text is concave, leading many to believe that the stone was polished down and reused numerous times.[12]

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

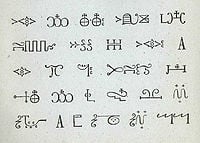

Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing was used by the Míkmaq, Indians native to Nova Scotia and its surrounding areas.

The Mi’kmaq script primarily consisted of a collection of ideograms. The Mi’kmaq had a rich oral tradition, and it has been suggested that hieroglyphs were used mainly as either a memory aid or trail marking. Since written language was not a major part of Mi’kmaq life, the ideograms eventually fell out of use, and were eventually replaced by phonetic versions of the Mi’kmaq language using the Latin alphabet.[13]

Father le Clercq, a Roman Catholic missionary on the Gaspé Peninsula, noted in 1691 that he had seen some Míkmaq children writing with charcoal symbols on birchbark while he taught them prayers. This and other accounts of writing that pre-dates missionary visits refutes claims that the Mi’kmaq writing system was developed by missionaries as a way to teach Christian prayers, though it is still possible that the ideograms existed purely as mnemonic memory aids. Missionaries worked to develop and understand the writing system into a fully functional written language in order to translate prayers like The Lord’s Prayer, adding new ideographs to refer to concepts like God (a triangle to represent the trinity. [14]

Notes

- ↑ Hieroglyph. Encyclopædia Britannica, Retrieved December 08, 2008.

- ↑ Loy, Jim. 1997. Types of Signs in Egyptian. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Jourdan, Francesca. [The Narmer Palette.] Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 1995 p.12

- ↑ Wiens, Mi Chu. 1999. [Living Pictographs.] Library of Congress. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Ager, Simon. 2008. [Naxi Scripts.] Omniglot. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Ager, Simon. 2008. Mayan Script. Omniglot. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Bronze Age Writing on Crete: Hieroglyphs, Linear A, and Linear B, Athena Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2004. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Evans, Arthur. Writing in Prehistoric Greece, The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 30, p.91, 1900. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Daniels, Peter T. and William Bright, The World’s Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, p.120, 1996. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Daniels, Peter T. and William Bright, The World’s Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, pp.121-3, 1996. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Oldest Writing in the New World Discovered in Veracruz, Mexico, Brown University. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ About Mi’Kmaw “Hieroglyphics’, Mi’kmaq Spirit. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ About Mi’Kmaw “Hieroglyphics’, Mi’kmaq Spirit. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Robinson, Andrew. The story of writing with over 350 illustrations, 50 in color. New York: Thames & Hudson 2003. ISBN 0500281564

- Andrew Robinson (2007). Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Angelika Rauch (1997). The Hieroglyph of Tradition, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press.

- Douglas J (2007). Egypt and the Egyptians, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene. 2001. "Scripts: An Overview." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald B. Redford. Vol. 3. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 192–198 [194–195].

- Davies, William Vivian. 1990. "Egyptian Hieroglyphs." In Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. London: British Museum Press. 74–135.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: I. The Corpus. II. The Clay Bar from Malia, H20, Kadmos 29 (1990) 1-10.

- W. C. Brice, Cretan Hieroglyphs & Linear A, Kadmos 29 (1990) 171-2.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: III. The Inscriptions from Mallia Quarteir Mu. IV. The Clay Bar from Knossos, P116, Kadmos 30 (1991) 93-104.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script, Kadmos 31 (1992), 21-24.

- J.-P. Olivier, L. Godard, in collaboration with J.-C. Poursat, Corpus Hieroglyphicarum Inscriptionum Cretae (CHIC), Études Crétoises 31, De Boccard, Paris 1996, ISBN 2-86958-082-7.

- G. A. Owens, The Common Origin of Cretan Hieroglyphs and Linear A, Kadmos 35:2 (1996), 105-110.

- G. A. Owens, An Introduction to «Cretan Hieroglyphs»: A Study of «Cretan Hieroglyphic» Inscriptions in English Museums (excluding the Ashmolean Museum Oxford), Cretan Studies VIII (2002), 179-184.

- I. Schoep, A New Cretan Hieroglyphic Inscription from Malia (MA/V Yb 03), Kadmos 34 (1995), 78-80.

- J. G. Younger, The Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: A Review Article, Minos 31-32 (1996-1997) 379-400.

- Bruhns, Karen O. and Nancy L. Kelker, Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, and Alfredo Delgado Calderón (2007-03-09). Did the Olmec Know How to Write?. Science 315 (5817): pp.1365–1366.

- Houston, Stephen D. (2004). "Writing in Early Mesoamerica", in Stephen D. Houston (ed.): The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.274–309. ISBN 0-521-83861-4. OCLC 56442696.

- Rodríguez Martínez, Ma. del Carmen and Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, and Alfredo Delgado Calderón (2006-09-16). Oldest Writing in the New World. Science 313 (5793): pp.1610–1614.

- Skidmore, Joel (2006). The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing (PDF). Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Magni, Caterina (2008). "Olmec Writing. The Cascajal Block: New Perspectives", in Laurence Mattet (ed.): Arts & Cultures 2008: Antiquité, Afrique, Océanie, Asie, Amérique, revue annuelle des musées Barbier-Mueller, 9. Paris, Genève/Barcelona: Somogy Éditions d'art, in collaboration with The Association of Friends of the Barbier-Mueller Museum, pp.64–81. ISBN 978-2-7572-0163-3.

Yang, Zhengwen (2008). Zhengwen Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-08499-9.

Fang, Guoyu (2008). Guoyu Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-08271-1.

He, Zhiwu (2008). Zhiwu Naxi Study Collection. Beijing: Culture Publisher. ISBN 978-7-105-09099-0.

Crampton, Thomas (Feb. 12), "Hieroglyphic Script Fights for Life", International Herald Tribune

- Brigham Young University press-release on behalf of Brigham Young University archaeologist Stephen Houston and Yale University professor emeritus Michael Coe disputing the Justeson-Kaufman findings.*Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London.

- Houston, Stephen, and Michael Coe (2004) "Has Isthmian Writing Been Deciphered?," in Mexicon XXV:151-161.

- Justeson, John S., and Terrence Kaufman (1993), "A Decipherment of Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing" in Science, Vol. 259, 19 March 1993, pp. 1703-11.

- Justeson, John S., and Terrence Kaufman (1997) "A Newly Discovered Column in the Hieroglyphic Text on La Mojarra Stela 1: a Test of the Epi-Olmec Decipherment", Science, Vol. 277, 11 July 1997, pp. 207-10.

- Justeson, John S., and Terrence Kaufman (2001) Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing and Texts.

- Lo, Lawrence; "Epi-Olmec," at Ancient Scripts.com] (accessed January 2008).

- Pérez de Lara, Jorge, and John Justeson "Photographic Documentation of Monuments with Epi-Olmec Script/Imagery", Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI).

- Schuster, Angela M. H. (1997) "Epi-Olmec Decipherment" in Archaeology, online (accessed January 2008).

- Hewson, John. 1982. Micmac Hieroglyphs in Newfoundland. Languages in Newfoundland and Labrador, ed. by Harold Paddock, 2nd ed., 188-199. St John's, Newfoundland: Memorial University

- Hewson, John. 1988. Introduction to Micmac Hieroglyphics. Cape Breton Magazine 47:55-61. (text of 1982, plus illustrations of embroidery and some photos)

- [Kauder, Christian]. 1921. Sapeoig Oigatigen tan teli Gômgoetjoigasigel Alasotmaganel, Ginamatineoel ag Getapefiemgeoel; Manuel de Prières, instructions et changs sacrés en Hieroglyphes micmacs; Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms & Hymns in Micmac Ideograms. New edition of Father Kauder's Book published in 1866. Ristigouche, Québec: The Micmac Messenger.

- Lenhart, John. History relating to Manual of prayers, instructions, psalms and humns in Micmac Ideograms used by Micmac Indians fof Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. Sydney, Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Native Communications Society.

- Schmidt, David L., and B. A. Balcom. 1995. "The Règlements of 1739: A Note on Micmac Law and Literacy," in Acadiensis. XXIII, 1 (Autumn 1993) pp 110-127. ISSN 0044-5851

- Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. 1995. Míkmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-55109-069-4

External links

- http://www.ancientscripts.com/luwian.html

- Luwian Hieroglyphics from the Indo-European Database

- Sign list, with logographic and syllabic readings

- [ http://www.evertype.com/gram/olmec.html Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs]

- “Oldest” New World writing found by Helen Briggs for BBC News, 14 September 2006.

- Oldest writing in the New World discovered in Veracruz, Mexico from EurekAlert, 14 September 2006.

- 3,000-year-old script on stone found in Mexico by John Noble Wilford for the New York Times, 15 September 2006.

- Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere by John Noble Wilford for the New York Times, 15 September 2006.

- Earliest New World Writing Discovered by Christopher Joyce for NPR, 15 September 2006.

- Unknown Writing System Uncovered On Ancient Olmec Tablet from Science a GoGo, 15 September 2006.

- Stone Slab Bears Earliest Writing in Americas by Andrew Bridges for AP, 15 September 2006.

- Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs by Michael Everson, 18 September 2006.

- The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing Joel Skidmore, Precolumbia Mesoweb Press,

- High resolution image of the Isthmian glyph table

- Tuxtla Statuette photograph

- Drawing of La Mojarra Stela 1

- High resolution photo of the Coe/Huston Mask

- Míkmaq Portraits Collection Includes tracings and images of Míkmaq petroglyphs

- Micmac at ChristusRex.org A large collection of scans of prayers in Míkmaq hieroglyphs.

- Écriture sacrée en Nouvelle France: Les hiéroglyphes micmacs et transformation cosmologique (PDF, in French) A discussion of the origins of Míkmaq hieroglyphs and sociocultural change in 17th century Micmac society.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Hieroglyph history

- Cursive_hieroglyphs history

- Dongba_script history

- Cretan_hieroglyphs history

- Anatolian_hieroglyphs history

- Maya_script history

- Cascajal_Block history

- Isthmian_script history

- Mi'kmaq_hieroglyphic_writing history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.