Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elizabeth Beecher Stowe, (June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) is an American writer and reformer, best known as the author of the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. The sensationally popular novel presented a emmpathetic portrait slave life and played a significant role growing opposition to slavery prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Stowe wrote the work in reaction to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it illegal to assist an escaped slave. In the book she expresses her moral outrage at the institution of slavery and its destructive effects on both races and especially on maternal bonds.

Stowe was born into a family with deep religious convictions and a social conscience that would leave a historical legacy in educational reform, the revision of Calvinist theology, abolition, literature, and women’s suffrage.

After the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Stowe became an international celebrity and a popular author. In addition to novels, poetry and essays, she wrote non-fiction books on a wide range of subjects including homemaking and the raising of children, and religion. She wrote in an informal conversational style, and presented herself as an average wife and mother. Her realistic style and her narrative use of local dialect predated works like Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn by 30 years.

Early Life

Born in Litchfield, Connecticut and raised primarily in Hartford, Harriet Beecher Stowe was the seventh of 11 children born to Rev. Lyman Beecher, an abolitionist Congregationalist preacher, from Boston and Roxana Foote Beecher, a granddaughter of General Andrew Ward who was a member of General George Washington’s staff in the Revolutionary War. Many of her brothers and sisters became famous reformers. Henry Ward Beecher(1813-1887), a noted minister in Brooklyn, New York, was active in the abolitionist movement. Catharine Beecher (1800-1878) founded many schools for young women throughout the country and was a prolific author while her half-sister, Isabella Beecher (1822-1907), became active in the women's suffrage movement.

Her mother died of tuberculosis at 41, when Harriet was only four. Two years later a stepmother took over the household. Stowe was named after her aunt, Harriet Foote, who deeply influenced her thinking, especially with her strong belief in culture. Samuel Foote, her uncle, encouraged her to read works of Lord Byron and Sir Walter Scott.

When Stowe was eleven, she entered the seminary at Hartford, Connecticut, kept by her elder sister Catherine. The school had advanced curriculum and she learned languages, natural and mechanical science, composition, ethics, logic, and mathematics. At that time, Hartford Female Seminary was one of only a handful of schools that took the education of girls seriously. Four years after entering as a student she became an assistant teacher.

Her father married again and in 1832 the family moved to Cincinnati, Ohio where he became the President of Lane Theological Seminary. Cincinnati was a hotbed of the abolitionist movement and this is where she gained first-hand knowledge of slavery and the Underground railroad that led her to write Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Catherine and Harriet founded a new seminary in Cincinnati, the Western Female Institute and together they wrote a children's geography book.

Marriage and family

In 1836 Harriet Beecher married Calvin Stowe, a clergyman and widower who was a professor at Lane Theological Seminary. Calvin's wife Eliza befriended Harriet Beecher when she first arrived. When Eliza died young, Harriet and Calvin were drawn together by a shared loss. Their first children were twin girls whom they chose to name Harriet and Eliza. Throughout their marriage, Calvin encouraged Harriet in her career as an author.

Six of the Stowe's seven children were born in Cincinnati. The twin girls were born on September 29, 1836. They were followed by her son Henry Ellis (1838), Frederick William (1840), Georgiana May (1843), Samuel Charles (1848), and Charles Edward (1850).

In 1850 Professor Stowe joined the faculty of his alma mater, Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. The Stowe family moved to Maine and lived in Brunswick until 1853. From Brunswick, the Stowes moved to Andover, Massachusetts, where Calvin became a professor of theology at Andover Theological Seminary from 1853 to 1864. After his retirement, the family moved to Hartford, Connecticut.

During the Hartford years Calvin wrote the Origin and History of the Books of the Bible (1867). This scholarly work was one of the first books to examine the Bible from an historical point of view. Calvin received $10,000 in royalties from the book, considered a large amount of money in those days.

In the 1860s the Stowes purchased property in Mandarin, Florida, and began to travel south each winter. While in Florida Stowe helped establish schools for African American children and fostered the development of an ecumenical church open to members of all denominations. Her brother Charles (a minister, composer of religious hymns, and prolific author) joined the Stowes in Florida, to help the cause of the newly freed people.

Final years

In Hartford Harriet Beecher Stowe built her dream house, Oakholm, but the high maintenance cost and the encroachment of factories caused her to sell it in 1870. In 1873, she moved to her last home, the brick Victorian Gothic cottage-style house on Forest Street.

While living on Forest Street in Hartford Stowe and her family became acquainted with Samuel Clemens. Clemens and his family moved into a house adjacent to theirs and under the pen name Mark Twain wrote some of his most famous books while living in this house. Clemens was just about the same age as the Stowe twins, Harriet and Eliza.

Stowe died in 1896, two years after her husband, in Hartford. She is buried on the grounds of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio is the former home of her father Lyman Beecher on the former campus of the Lane Seminary. Harriet lived here until her marriage. It is open to the public and operated as an historical and cultural site.

Writing career

In Cincinnati Stowe became a member of the Semi-Colon Club, a local literary society in which members wrote articles which were read and discussed by other participants. Her experiences in this club sharpened her writing style. During her early married years, Harriet began to publish stories and magazine articles to supplement the family income.

In 1834 Stowe began her literary career when she won a prize contest of the Western Monthly Magazine, and soon she was a regular contributor of stories and essays. Her first book, The Mayflower, appeared in 1843.

While she lived in Cincinnati, Stowe co-authored a book with her sister, Primary Geography for Children. After the publication of this book Stowe received a special commendation from the Bishop of Cincinnati because it conveyed a positive image of the Catholic religion. Stowe's religious tolerance was unusual for Protestants at the time.

Stowe's most successful book, and the reason she is remembered in history, was Uncle Tom's Cabin. First published in serial form from 1851 to 1852 in an abolitionist organ, the National Era, Uncle Tom's Cabin sold more than 10,000 copies the first week it was published as a book. In the story 'Uncle Tom' is bought and sold three times and finally beaten to death by his last owner. The book was quickly translated into 37 languages and it sold over half a million copies in the United States over five years. It was turned into a play that also became very popular.

Speaking of her experience of writing the book she once said, "I could not control the story, the Lord himself wrote it. I was but an instrument in His hands and to Him should be given all the praise." It is reported that when Abraham Lincoln met the Stowe he joked, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

Stowe's fame opened doors to the national literary magazines. She started to publish her writings in The Atlantic Monthly and later in Independent and in Christian Union. For some time she was the most celebrated woman writer in The Atlantic Monthly and in the New England literary clubs. In 1853, 1856, and 1859 Stowe made journeys to Europe, where she became friends with George Eliot, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Lady Byron. However, the British public opinion turned against her when she charged Lord Byron with incestuous relations with his half-sister. In Lady Byron Vindicated (1870) she publicly declared her accusation. Both The Atlantic Monthly and Stowe suffered serious criticism after it was published.

Attacks on the veracity of her portrayal of the South led Stowe to publish The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), in which she presented her source material. A second anti-slavery novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856), told the story of a dramatic attempt at slave rebellion.

After the Civil War the popularity of Uncle Tom's Cabin began to decline. 'Uncle Tom' became a pejorative term, meaning undue subservience to white people on the part of black people.

Stowe's later works did not gain the same popularity as Uncle Tom's Cabin. She published novels, studies of social life, essays, and a small volume of religious poems. The Stowes lived in Hartford in summer and spent their winters in Florida, where they had a luxurious home. The Pearl of Orr's Island (1862), Old-Town Folks (1869), and Poganuc People (1878) were partly based on her husband's childhood reminiscences and are among the first examples of local color writing in New England.

- For other uses, see Harriet Beecher Stowe (disambiguation).

| |

| Author | Harriet Beecher Stowe |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Hammatt Billings (1st edition) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novel |

| Publisher | National Era (as a serial) & John P. Jewett and Company (in two volumes) |

| Released | March 20, 1853 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | NA |

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the United States, so much so in the latter case that the novel intensified the sectional conflict leading to the American Civil War.[1]

Stowe, a Connecticut-born preacher at the Hartford Female Academy and an active abolitionist, focused the novel on the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering Black slave around whom the stories of other characters—both fellow slaves and slave owners—revolve. The sentimental novel depicts the cruel reality of slavery while also asserting that Christian love can overcome something as destructive as enslavement of fellow human beings.[2][3][4]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel of the 19th century,[5] and the second best-selling book of that century, following the Bible.[6] It is credited with helping fuel the abolitionist cause in the 1850s.[7] In the first year after it was published, 300,000 copies of the book were sold in the United States alone. The book's impact was so great that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe at the start of the American Civil War, Lincoln is often quoted as having declared, "So this is the little lady who made this big war."[8]

The book, and even more the plays it inspired, also helped create a number of stereotypes about Blacks,[9] many of which endure to this day. These include the affectionate, dark-skinned mammy; the Pickaninny stereotype of black children; and the Uncle Tom, or dutiful, long-suffering servant faithful to his white master or mistress. In recent years, the negative associations with Uncle Tom's Cabin have, to an extent, overshadowed the historical impact of the book as a "vital antislavery tool."[10]

Sources for the novel

Stowe, a Connecticut-born teacher at the Hartford Female Academy and an active abolitionist, wrote the novel as a response to the 1850 passage of the second Fugitive Slave Act (which punished those who aided runaway slaves and diminished the rights of fugitives as well as freed Blacks). Much of the book was composed in Brunswick, Maine, where her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe, taught at his alma mater Bowdoin College.[11]

Stowe was partly inspired to create Uncle Tom's Cabin by the autobiography of Josiah Henson, a black man who lived and worked on a 3,700 acre (15 km²) tobacco plantation in North Bethesda, Maryland owned by Isaac Riley.[12] Henson escaped slavery in 1830 by fleeing to the Province of Upper Canada (now Ontario), where he helped other fugitive slaves arrive and become self-sufficient, and where he wrote his memoirs. Harriet Beecher Stowe evidently acknowledged that Henson's writings inspired Uncle Tom's Cabin.[13] When Stowe's work became a best-seller, Henson republished his memoirs as The Memoirs of Uncle Tom, and traveled extensively in America and Europe.[12] Stowe's novel lent its name to Henson's home—Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site, near Dresden, Ontario—which since the 1940s has been a museum. The actual cabin Henson lived in while he was a slave, still exists in Montgomery County, Maryland.

American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, a volume co-authored by Theodore Dwight Weld and the Grimké sisters, is also a source of some of the novel's content.[14] Stowe also said she based the novel on a number of interviews with escaped slaves during the time when Stowe was living in Cincinnati, Ohio, across the Ohio River from Kentucky, a slave state. In Cincinnati the Underground Railroad had local abolitionist sympathizers and was active in efforts to help runaway slaves on their escape route from the South.

Stowe mentioned a number of the inspirations and sources for her novel in A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853). This non-fiction book was intended to verify Stowe's claims about the evils of slavery.[15] However, later research indicated that Stowe did not actually read many of the book's cited works until after the publication of her novel.[15]

Publication

Uncle Tom's Cabin first appeared as a 40-week serial in National Era, an abolitionist periodical, starting with the June 5, 1851 issue. Because of the story's popularity, the publisher John Jewett contacted Stowe about turning the serial into a book. While Stowe questioned if anyone would read Uncle Tom's Cabin in book form, she eventually consented to the request.

Convinced the book would be popular, Jewett made the unusual decision (for that time) to have six fullpage illustrations by Hammatt Billings engraved for the first printing.[16] Published in book form on March 20, 1852, the novel soon sold out its complete print run. A number of other editions were soon printed (including a deluxe edition in 1853, featuring 117 illustrations by Billings).[17]

In the first year of publication, 300,000 copies of Uncle Tom's Cabin were sold. The book eventually became the best-selling novel in the world during the 19th century (and the second best-selling book after the Bible), with the book being translated into every major language.[6] A number of the early editions carried an introduction by Rev James Sherman, a Congregational minister in London noted for his abolitionist views.

Uncle Tom's Cabin sold equally well in England, with the first London edition appearing in May, 1852 and selling 200,000 copies.[18] In a few years over 1.5 million copies of the book were in circulation in England, although most of these were pirated copies (a similar situation occurred in the United States).[19]

Plot summary

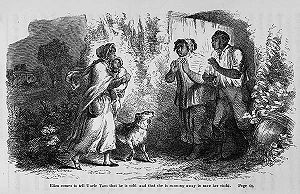

Eliza escapes with her son, Tom sold "down the river"

The book opens with a Kentucky farmer named Arthur Shelby facing the loss of his farm because of debts. Even though he and his wife, Emily Shelby, believe that they have a benevolent relationship with their slaves, Shelby decides to raise the needed funds by selling two of them—Uncle Tom, a middle-aged man with a wife and children, and Harry, the son of Emily Shelby’s maid Eliza—to a slave trader. Emily Shelby hates the idea of doing this because she had promised her maid that her child would never be sold; Emily's son, George Shelby, hates to see Tom go because he sees the man as his friend and mentor.

When Eliza overhears Mr. and Mrs. Shelby discussing plans to sell Tom and Harry, Eliza determines to run away with her son. The novel states that Eliza made this decision not because of physical cruelty, but by her fear of losing her only surviving child (she had already lost two children due to miscarriage). Eliza departs that night, leaving a note of apology to her mistress.

While all of this is happening, Uncle Tom is sold and placed on a riverboat, which sets sail down the Mississippi River. While on board, Tom meets and befriends a young white girl named Eva. When Eva falls into the river, Tom saves her. In gratitude, Eva's father, Augustine St. Clare, buys Tom from the slave trader and takes him with the family to their home in New Orleans. During this time, Tom and Eva begin to relate to one another because of the deep Christian faith they both share.

Eliza's family hunted, Tom's life with St. Clare

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada. However, they are now being tracked by a slave hunter named Tom Loker. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot Loker. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby Quaker settlement for medical treatment.

Back in New Orleans, St. Clare debates slavery with his Northern cousin Ophelia who, while opposing slavery, is prejudiced against Black people. St. Clare, however, believes he is not biased, even though he is a slave owner. In an attempt to show Ophelia that her views on Blacks are wrong, St. Clare purchases Topsy, a young black slave. St. Clare then asks Ophelia to educate Topsy.

After Tom has lived with the St. Clares for two years, Eva grows very ill. Before she dies she experiences a vision of heaven, which she shares with the people around her. As a result of her death and vision, the other characters resolve to change their lives, with Ophelia promising to throw off her personal prejudices against Blacks, Topsy saying she will better herself, and St. Clare pledging to free Uncle Tom.

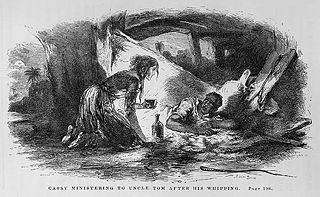

Tom sold to Simon Legree

Before St. Clare can follow through on his pledge, he dies after being stabbed while entering a New Orleans tavern. His wife reneges on her late husband's vow and sells Tom at auction to a vicious plantation owner named Simon Legree. Legree (who is not a native southerner but a transplanted northerner) takes Tom to rural Louisiana, where Tom meets Legree's other slaves, including Emmeline (whom Legree purchased at the same time). Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Tom receives a brutal beating, and Legree resolves to crush Tom's faith in God. But Tom refuses to stop reading his Bible and comforting the other slaves as best he can. While at the plantation, Tom meets Cassy, another of Legree's slaves. Cassy was previously separated from her son and daughter when they were sold; unable to endure the pain of seeing another child sold, she killed her third child.

At this point Tom Loker returns to the story. Loker has changed as the result of being healed by the Quakers. George, Eliza, and Harry have also obtained their freedom after crossing into Canada. In Louisiana, Uncle Tom almost succumbs to hopelessness as his faith in God is tested by the hardships of the plantation. However, he has two visions, one of Jesus and one of Eva, which renew his resolve to remain a faithful Christian, even unto death. He encourages Cassy to escape, which she does, taking Emmeline with her. When Tom refuses to tell Legree where Cassy and Emmeline have gone, Legree orders his overseers to kill Tom. As Tom is dying, he forgives the overseers who savagely beat him. Humbled by the character of the man they have killed, both men become Christians. Very shortly before Tom's death, George Shelby (Arthur Shelby's son) arrives to buy Tom’s freedom, but finds he is too late.

Final section

On their boat ride to freedom, Cassy and Emmeline meet George Harris' sister and accompany her to Canada. Once there, Cassy discovers that Eliza is her long-lost daughter who was sold as a child. Now that their family is together again, they travel to France and eventually Liberia, the African nation created for former American slaves. There they meet Cassy's long-lost son. George Shelby returns to the Kentucky farm and frees all his slaves. George tells them to remember Tom's sacrifice and his belief in the true meaning of Christianity.

Major characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom, the title character, was initially seen as a noble long-suffering Christian slave. In more recent years, his name has become an epithet directed towards African-Americans who are accused of selling out to whites (for more on this, see the creation and popularization of stereotypes section). Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero"[20] and praiseworthy person. Throughout the book, far from allowing himself to be exploited, Tom stands up for his beliefs and is grudgingly admired even by his enemies.

Eliza

A slave (personal maid to Mrs. Shelby), she escapes to the North with her five-year old son Harry after he is sold to Mr. Haley. Her husband, George, eventually finds Eliza and Harry in Ohio, and emigrates with them to Canada, then France and finally Liberia.

The character Eliza was inspired by an account given at Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati by John Rankin to Stowe's husband Calvin, a professor at the school. According to Rankin, in February, 1838 a young slave woman had escaped across the frozen Ohio River to the town of Ripley with her child in her arms and stayed at his house on her way further north.[21]

Eva

Eva, whose real name is Evangeline St. Clare, is the daughter of Augustine St. Clare. Eva enters the narrative when Uncle Tom is traveling via steamship to New Orleans to be sold, and he rescues the 5 or 6 year-old girl from drowning. Eva begs her father to buy Tom, and he becomes the head coachman at the St. Clare plantation. He spends most of his time with the angelic Eva, however.

Eva constantly talks about love and forgiveness, even convincing the dour slave girl Topsy that she deserves love. She even manages to touch the heart of her sour aunt, Ophelia. Some consider Eva to be a prototype of the character archetype known as the Mary Sue.

Eventually Eva falls ill. Before dying, she gives a lock of her hair to each of the slaves, telling them that they must become Christians so that they may see each other in Heaven. On her deathbed, she convinces her father to free Tom, but because of circumstances the promise never materializes.

Simon Legree

A villainous and cruel slave owner—a Northerner by birth—whose name has become synonymous with greed. His goal is to demoralize Tom and break him of his religious faith.

Topsy

A "ragamuffin" young slave girl of unknown origin. When asked if she knows who made her, she professes ignorance of both God and a mother, saying "I s'pect I growed. Don't think nobody never made me." She was transformed by Little Eva's love. Topsy is often seen as the origin of the pickaninny stereotype of Black children and Black dolls. During the early-to-mid 1900s, several doll manufacturers created Topsy and Topsy-type dolls.

The phrase "growed like Topsy" (later "grew like Topsy"; now somewhat archaic) passed into the English language, originally with the specific meaning of unplanned growth, later sometimes just meaning enormous growth.[22]

Other characters

There are a number of secondary and minor characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Among the more notable are:

- Arthur Shelby, Tom's master in Kentucky. Shelby is characterized as a "kind" slaveowner and a stereotypical Southern gentleman.

- Emily Shelby, Arthur Shelby's wife. A deeply religious woman who strives to be a kind and moral influence upon her slaves. She is appalled when her husband sells his slaves with a slave trader. As a woman, she had no legal way to stop this, as all property belonged to her husband.

- George Shelby, Arthur and Emily's son. Sees Tom as a "friend" and as the perfect Christian.

- Augustine St. Clare, Tom's second owner and father of Eva. Of the slaveowners in the novel, the most sympathetic character. St. Clare recognizes the evil in chattel slavery, but is not ready to relinquish the wealth it brings him. After his daughter's death he becomes more religious and starts to read the Bible to Tom. His sometimes good intentions ultimately come to nothing.

Major themes

Uncle Tom's Cabin is dominated by a single theme: the evil and immorality of slavery.[23] While Stowe weaves other subthemes throughout her text, such as the moral authority of motherhood and the redeeming possibilities offered by Christianity,[3] she emphasizes the connections between these and the horrors of slavery. Stowe pushed home her theme of the immorality of slavery on almost every page of the novel, sometimes even changing the story's voice so she could give a "homily" on the destructive nature of slavery[24] (such as when a white woman on the steamboat carrying Tom further south states, "The most dreadful part of slavery, to my mind, is its outrages of feelings and affections—the separating of families, for example.").[25] One way Stowe showed the evil of slavery[18] was how this "peculiar institution" forcibly separated families from each other.[26]

Because Stowe saw motherhood as the "ethical and structural model for all of American life,"[27] and also believed that only women had the moral authority to save[28] the United States from the demon of slavery, another major theme of Uncle Tom's Cabin is the moral power and sanctity of women. Through characters like Eliza, who escapes from slavery to save her young son (and eventually reunites her entire family), or Little Eva, who is seen as the "ideal Christian",[29] Stowe shows how she believed women could save those around them from even the worst injustices. While later critics have noted that Stowe's female characters are often domestic clichés instead of realistic women,[30] Stowe's novel "reaffirmed the importance of women's influence" and helped pave the way for the women's rights movement in the following decades.[31]

Stowe's puritanical religious beliefs show up in the novel's final, over-arching theme, which is the exploration of the nature of Christianity[3] and how she feels Christian theology is fundamentally incompatible with slavery.[32] This theme is most evident when Tom urges St. Clare to "look away to Jesus" after the death of St. Clare's beloved daughter Eva. After Tom dies, George Shelby eulogizes Tom by saying, "What a thing it is to be a Christian."[33] Because Christian themes play such a large role in Uncle Tom's Cabin—and because of Stowe's frequent use of direct authorial interjections on religion and faith—the novel often takes the "form of a sermon."[34]

Style

Uncle Tom's Cabin is written in the sentimental[35] and melodramatic style common to 19th century sentimental novels[5] and domestic fiction (also called women's fiction). These genres were the most popular novels of Stowe's time and tended to feature female main characters and a writing style which evoked a reader's sympathy and emotion.[36] Even though Stowe's novel differs from other sentimental novels by focusing on a large theme like slavery and by having a man as the main character, she still set out to elicit certain strong feelings from her readers (such as making them cry at the death of Little Eva).[37] The power in this type of writing can be seen in the reaction of contemporary readers. Georgiana May, a friend of Stowe's, wrote a letter to the author stating that "I was up last night long after one o'clock, reading and finishing Uncle Tom's Cabin. I could not leave it any more than I could have left a dying child."[38] Another reader is described as obsessing on the book at all hours and having considered renaming her daughter Eva.[39] Evidently the death of Little Eva affected a lot of people at that time, because in 1852 alone 300 baby girls in Boston were given that name.[39]

Despite this positive reaction from readers, for decades literary critics dismissed the style found in Uncle Tom's Cabin and other sentimental novels because these books were written by women and so prominently featured "women's sloppy emotions."[40] One literary critic said that had the novel not been about slavery, "it would be just another sentimental novel,"[41] while another described the book as "primarily a derivative piece of hack work."[42] George Whicher turned his nose up at the book in his Literary History of the United States by saying it was "Sunday-school fiction" and full of "broadly conceived melodrama, humor, and pathos."[43]

However, in 1985 Jane Tompkins changed this view of Uncle Tom's Cabin with her landmark book In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction.[40] Tompkins praised the very sentimental style so many other critics had dismissed, noting that sentimental novels showed how women's emotions had the power to change the world for the better. She also said that the popular domestic novels of the 19th century, including Uncle Tom's Cabin, were remarkable for their "intellectual complexity, ambition, and resourcefulness"; and that Uncle Tom's Cabin offers a "critique of American society far more devastating than any delivered by better-known critics such as Hawthorne and Melville."[43]

Despite this changing view of Uncle Tom's Cabin's style, because the book is written so differently from most modern novels, today's readers can find the book's prose to be dense, overdone, or even "corny".[44]

Reactions to the novel

Uncle Tom's Cabin has exerted an influence "equaled by few other novels in history."[45] Upon publication, Uncle Tom's Cabin ignited a firestorm of protest from defenders of slavery (who created a number of books in response to the novel) while the book elicited praise from abolitionists. As a best-seller, the novel heavily influenced later protest literature (such as The Jungle by Upton Sinclair).

Contemporary and world reaction

Immediately upon publication, Uncle Tom's Cabin outraged people in the American South.[18] The novel was also roundly criticized by slavery supporters.

Acclaimed Southern novelist William Gilmore Simms declared the work utterly false,[46] while others called the novel criminal and slanderous.[47] Reactions ranged from a bookseller in Mobile, Alabama who was forced to leave town for selling the novel[18] to threatening letters sent to Stowe herself (including a package containing a slave's severed ear).[18] Many Southern writers, like Simms, soon wrote their own books in opposition to Stowe's novel (see the Anti-Tom section below).[48]

Some critics highlighted Stowe's paucity of life-experience relating to Southern life, which (in their view) led her to create inaccurate descriptions of the region. For instance, she had never set foot on a Southern plantation. However, Stowe always said she based the characters of her book on stories she was told by runaway slaves in Cincinnati, Ohio, where Stowe lived. It is reported that, "She observed firsthand several incidents which galvanized her to write [the] famous anti-slavery novel. Scenes she observed on the Ohio River, including seeing a husband and wife being sold apart, as well as newspaper and magazine accounts and interviews, contributed material to the emerging plot."[49]

In response to these criticisms, in 1853 Stowe published A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, an attempt to document the veracity of the novel's depiction of slavery. In the book, Stowe discusses each of the major characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin and cites "real life equivalents" to them while also mounting a more "aggressive attack on slavery in the South than the novel itself had."[15] Like the novel, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin was also a best-seller. It should be noted, though, that while Stowe claimed A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin documented her previously consulted sources, she actually read many of the cited works only after the publication of her novel.[15]

Despite these supposed and actual flaws in Stowe's research, and despite the shrill attacks from defenders of slavery, the novel still captured the imagination of many Americans. According to Stowe's son, when Abraham Lincoln met her in 1862 Lincoln commented, "So this is the little lady who started this great war."[8] Historians are undecided if Lincoln actually said this line, and in a letter that Stowe wrote to her husband a few hours after meeting with Lincoln no mention of this comment was made.[50] Since then, many writers have credited this novel with focusing Northern anger at the injustices of slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law[50] and helping to fuel the abolitionist movement.[51] Union General and politician James Baird Weaver said that the book convinced him to become active in the abolitionist movement.[52]

Uncle Tom's Cabin also created great interest in England. The first London edition appeared in May, 1852, and sold 200,000 copies.[18] Some of this interest was because of British antipathy to America. As one prominent writer explained, "The evil passions which 'Uncle Tom' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance [of slavery], but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America—we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system—our Tories hate her democrats—our Whigs hate her parvenus—our Radicals hate her litigiousness, her insolence, and her ambition. All parties hailed Mrs. Stowe as a revolter from the enemy."[53] Charles Francis Adams, the American minister to Britain during the war, argued later that, "Uncle Tom's Cabin; or Life among the Lowly, published in 1852, exercised, largely from fortuitous circumstances, a more immediate, considerable and dramatic world-influence than any other book ever printed."[54]

The book has been translated into almost every language, including Chinese (with translator Lin Shu creating the first Chinese translation of an American novel) and Amharic (with the 1930 translation created in support of Ethiopian efforts to end the suffering of blacks in that nation).[55] The book was so widely read that Sigmund Freud reported a number of patients with sado-masochistic tendencies who he believed had been influenced by reading about the whipping of slaves in Uncle Tom's Cabin.[56]

Literary significance and criticism

As the first widely read political novel in the United States,[57] Uncle Tom's Cabin greatly influenced development of not only American literature but also protest literature in general. Later books which owe a large debt to Uncle Tom's Cabin include The Jungle by Upton Sinclair and Silent Spring by Rachel Carson.[58]

Despite this undisputed significance, the popular perception of Uncle Tom's Cabin is as "a blend of children's fable and propaganda."[59] The novel has also been dismissed by a number of literary critics as "merely a sentimental novel,"[60] while critic George Whicher stated in his Literary History of the United States that "Nothing attributable to Mrs. Stowe or her handiwork can account for the novel's enormous vogue; its author's resources as a purveyor of Sunday-school fiction were not remarkable. She had at most a ready command of broadly conceived melodrama, humor, and pathos, and of these popular cements she compounded her book."[43]

Other critics, though, have praised the novel. Edmund Wilson stated that "To expose oneself in maturity to Uncle Tom's Cabin may … prove a startling experience."[59] Jane Tompkins states that the novel is one of the classics of American literature and wonders if many literary critics aren't dismissing the book because it was simply too popular during its day.[43]

Over the years scholars have postulated a number of theories about what Stowe was trying to say with the novel (aside from the obvious themes, such as condemning slavery). For example, as an ardent Christian and active abolitionist, Stowe placed many of her religion's beliefs into the novel.[61] Some scholars have stated that Stowe saw her novel as offering a solution to the moral and political dilemma that troubled many slavery opponents: whether engaging in prohibited behavior was justified in opposing evil. Was the use of violence to oppose the violence of slavery and the breaking of proslavery laws morally defensible? Which of Stowe's characters should be emulated, the passive Uncle Tom or the defiant George Harris?[62] Stowe's solution was similar to Ralph Waldo Emerson's: God's will would be followed if each person sincerely examined his principles and acted on them.[62]

Scholars have also seen the novel as expressing the values and ideas of the Free Soil Movement.[63] In this view, the character of George Harris embodies the principles of free labor, while the complex character of Ophelia represents those Northerners who condoned compromise with slavery. In contrast to Ophelia is Dinah, who operates on passion. During the course of the novel Ophelia is transformed, just as the Republican Party (3 years later) proclaimed that the North must transform itself and stand up for its antislavery principles.[63]

Feminist theory can also be seen at play in Stowe's book, with the novel as a critique of the patriarchal nature of slavery.[64] For Stowe, blood relations rather than paternalistic relations between masters and slaves formed the basis of families. Moreover, Stowe viewed national solidarity as an extension of a person's family, thus feelings of nationality stemmed from possessing a shared race. Consequently she advocated African colonization for freed slaves and not amalgamation into American society.

The book has also been seen as an attempt to redefine masculinity as a necessary step toward the abolition of slavery.[65] In this view, abolitionists had begun to resist the vision of aggressive and dominant men that the conquest and colonization of the early 19th century had fostered. In order to change the notion of manhood so that men could oppose slavery without jeopardizing their self-image or their standing in society, some abolitionists drew on principles of women's suffrage and Christianity as well as passivism, and praised men for cooperation, compassion, and civic spirit. Others within the abolitionist movement argued for conventional, aggressive masculine action. All the men in Stowe's novel are representations of either one kind of man or the other.[65]

Creation and popularization of stereotypes

In recent decades, scholars and readers have criticized the book for what are seen as condescending racist descriptions of the book's black characters, especially with regard to the characters' appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate.[66] The novel's creation and use of common stereotypes about African Americans[9] is important because Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel in the world during the 19th century.[6] As a result, the book (along with images illustrating the book[67] and associated stage productions) had a major role in permanently ingraining these stereotypes into the American psyche.[68]

Among the stereotypes of Blacks in Uncle Tom's Cabin are:[10]

- The "happy darky" (in the lazy, carefree character of Sam);

- The light-skinned tragic mulatto as a sex object (in the characters of Eliza, Cassy, and Emmeline);

- The affectionate, dark-skinned female mammy (through several characters, including Mammy, a cook at the St. Clare plantation).

- The Pickaninny stereotype of black children (in the character of Topsy);

- The Uncle Tom, or African American who is too eager to please white people (in the character of Uncle Tom). Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero." The stereotype of him as a "subservient fool who bows down to the white man" evidently resulted from staged "Tom Shows," over which Stowe had no control.[20]

In the last few decades these negative associations have to a large degree overshadowed the historical impact of Uncle Tom's Cabin as a "vital antislavery tool."[10] The beginning of this change in the novel's perception had its roots in an essay by James Baldwin titled "Everybody’s Protest Novel." In the essay, Baldwin called Uncle Tom’s Cabin a "very bad novel" which was also racially obtuse and aesthetically crude.[69]

In the 1960s and '70s, the Black Power and Black Arts Movements attacked the novel, saying that the character of Uncle Tom engaged in "race betrayal," making Tom (in some eyes) worse than even the most vicious slave owner.[69] Criticisms of the other stereotypes in the book also increased during this time.

In recent years, though, scholars such as Henry Louis Gates Jr. have begun to reexamine Uncle Tom's Cabin, stating that the book is a "central document in American race relations and a significant moral and political exploration of the character of those relations."[69]

Anti-Tom literature

In response to Uncle Tom's Cabin, writers in the Southern United States produced a number of books to rebut Stowe's novel. This so-called Anti-Tom literature generally took a pro-slavery viewpoint, arguing that the issues of slavery as depicted in Stowe's book were overblown and incorrect. The novels in this genre tended to feature a benign white patriarchal master and a pure wife, both of whom presided over child-like slaves in a benevolent extended-family-style plantation. The novels either implied or directly stated that African Americans were a child-like people[70] unable to live their lives without being directly overseen by white people.[71]

Among the most famous anti-Tom books are The Sword and the Distaff by William Gilmore Simms, Aunt Phillis's Cabin by Mary Henderson Eastman, and The Planter's Northern Bride by Caroline Lee Hentz,[72] with the last author having been a close personal friend of Stowe's when the two lived in Cincinnati. Simms' book was published a few months after Stowe's novel and it contains a number of sections and discussions disputing Stowe's book and her view of slavery. Hentz's 1854 novel, widely-read at the time, but now largely forgotten, offers a defense of slavery as seen through the eyes of a northern woman—the daughter of an abolitionist, no less—who marries a southern slave owner.

In the decade between the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin and the start of the American Civil War, between twenty and thirty anti-Tom books were published. Among these novels are two books titled Uncle Tom's Cabin As It Is (one by W.L. Smith and the other by C.H. Wiley) and a book by John Pendleton Kennedy. More than half of these Anti-Tom books were written by white women, with Simms commenting at one point about the "Seemingly poetic justice of having the Northern woman (Stowe) answered by a Southern woman."[73]

Dramatic adaptations

Tom shows

Even though Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel of the 19th century, far more Americans of that time saw the story as a stage play or musical than read the book.[74] Eric Lott, in his book Uncle Tomitudes: Racial Melodrama and Modes of Production, estimates that at least three million people saw these plays, ten times the book's first-year sales.

Copyright issues

Given the lax copyright laws of the time, stage plays based on Uncle Tom's Cabin—"Tom shows"—began to appear while the story itself was still being serialized. Stowe refused to authorize dramatization of her work because of her puritanical distrust of drama (although she did eventually go to see George Aiken's version, and, according to Francis Underwood, was "delighted" by Caroline Howard's portrayal of Topsy).[75] Stowe's refusal left the field clear for any number of adaptations, some launched for (various) political reasons and others as simply commercial theatrical ventures.

There were then no international copyright laws. The book and plays were translated into several languages; Ms. Stowe saw no money, as much as "three fourths of her just and legitimate wages." [1]

On the plays

All Tom shows appear to have incorporated elements of melodrama and blackface minstrelsy.[76] These plays varied tremendously in their politics—some faithfully reflected Stowe's sentimentalized antislavery politics, while others were more moderate, or even pro-slavery.[75] Many of the productions featured demeaning racial caricatures of Black people,[76] while a number of productions also featured songs by Stephen Foster (including "My Old Kentucky Home," "Old Folks at Home," and "Massa's in the Cold Ground").[74] The best-known Tom Shows were those of George Aiken and H.J. Conway.[75]

The many stage variants of Uncle Tom's Cabin "dominated northern popular culture… for several years" during the 19th century[75] and the plays were still being performed in the early 20th century.

One of the unique and controversial variants of the Tom Shows was Walt Disney's 1933 Mickey's Mellerdrammer. Mickey's Mellerdrammer is a United Artists film released in 1933. The title is a corruption of "melodrama", thought to harken back to the earliest minstrel shows, as a film short based on a production of Uncle Tom's Cabin by the Disney characters. In that film, Mickey Mouse and friends stage their own production of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Mickey Mouse was already black-colored, but the advertising poster for the film shows Mickey dressed in blackface with exaggerated, orange lips; bushy, white sidewhiskers made out of cotton; and his now trademark white gloves.

Film adaptations

Uncle Tom's Cabin has been made into a number of film versions. Most of these movies were created during the silent film era (with Uncle Tom's Cabin being the most-filmed story of that time period).[77] This was due to the continuing popularity of both the book and Tom shows, meaning audiences were already familiar with the characters and the plot, making it easier for the film to be understood without spoken words.[77]

The first film version of Uncle Tom's Cabin was one of the earliest full-length movies (although full-length at that time meant between 10 and 14 minutes).[78] This 1903 film, directed by Edwin S. Porter, used white actors in blackface in the major roles and black performers only as extras. This version was evidently similar to many of the Tom Shows of earlier decades and featured a large number of black stereotypes (such as having the slaves dance in almost any context, including at a slave auction).[78]

In 1910, a 3-Reel Vitagraph Company of America production was directed by J. Stuart Blackton and adapted by Eugene Mullin. According to The Dramatic Mirror, this film was "a decided innovation" in motion pictures and "the first time an American company" released a dramatic film in 3 reels. Until then, full-length movies of the time were 15 minutes long and contained only one reel of film. The movie starred Florence Turner, Mary Fuller, Edwin R. Phillips, Flora Finch, Genevieve Tobin and Carlyle Blackwell, Sr.[79]

At least four more movie adaptations were created in the next two decades. The last silent film version came in 1927. Directed by Harry A. Pollard (who'd played Uncle Tom in a 1913 release of Uncle Tom's Cabin), this two-hour movie spent more than a year in production and was the third most expensive picture of the silent era (at a cost of $1.8 million). Black actor Charles Gilpin was originally cast in the title role, but was fired after the studio decided his "portrayal was too aggressive."[80] James B. Lowe then took over the character of Tom. One difference in this film from the novel is that after Tom dies, he returns as a vengeful spirit and confronts Simon Legree before leading the slave owner to his death. Black media outlets of the time praised the film, but the studio—fearful of a backlash from Southern and white film audiences—ended up cutting out controversial scenes, including the film's opening sequence at a slave auction (where a mother is torn away from her baby).[81] The story was adapted by Pollard, Harvey F. Thew and A. P. Younger, with titles by Walter Anthony. It starred James B. Lowe, Virginia Grey, George Siegmann, Margarita Fischer, Mona Ray and Madame Sul-Te-Wan.[80]

For several decades after the end of the silent film era, the subject matter of Stowe's novel was judged too sensitive for further film interpretation. In 1946, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer considered filming the story, but ceased production after protests led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[82]

A German language version, directed by Géza von Radványi, appeared in 1965 and was presented in the United States by exploitation film presenter Kroger Babb. The most recent film version was a television broadcast in 1987 directed by Stan Lathan and adapted by John Gay. It starred Avery Brooks, Phylicia Rashad, Edward Woodward, Jenny Lewis, Samuel L. Jackson and Endyia Kinney.

In addition to film adaptations, versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin have featured in a number of animated cartoons, including Walt Disney's Mickey's Mellerdrammer (1933), which features the classic Disney character performing the play in blackface with exaggerated, orange lips; the Bugs Bunny cartoon Southern Fried Rabbit (1953), where Bugs disguises himself as Uncle Tom and sings My Old Kentucky Home in order to cross the Mason-Dixon line; Uncle Tom's Bungalow (1937), a Warner Brother's cartoon supervised by Tex Avery; Eliza on Ice (1944), one of the earliest Mighty Mouse cartoons produced by Paul Terry; and Uncle Tom's Cabaña (1947), an eight-minute cartoon directed by Tex Avery.[82]

Uncle Tom's Cabin has also influenced a large number of movies, including Birth of a Nation. This controversial 1915 film deliberately used a cabin similar to Uncle Tom's home in the film's dramatic climax, where several white Southerners unite with their former enemy (Yankee soldiers) to defend what the film's caption says is their "Aryan birthright." According to scholars, this reuse of such a familiar cabin would have resonated with, and been understood by, audiences of the time.[83]

Among the other movies influenced by or making use of Uncle Tom's Cabin include Dimples (a 1936 Shirley Temple film),[82] "Uncle Tom's Uncle," (a 1926 Our Gang (The Little Rascals) episode),[82] the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I (in which a ballet called "Small House of Uncle Thomas" is performed in traditional Siamese style), and Gangs of New York (in which Leonardo DiCaprio and Daniel Day-Lewis's characters attend an imagined wartime adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin).

See also

- Origins of the American Civil War

- History of slavery in the United States

- Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement

- Uncle Tom

- Ramona, a novel that attempted to do the same for Native Americans in California that Uncle Tom's Cabin did for African Americans

- Onkel Toms Hütte, a Berlin U-Bahn station named for the book

Notes

- ↑ The Civil War in American Culture by Will Kaufman, Edinburgh University Press, 2006, page 18.

- ↑ Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Spark Publishers, 2002, page 19, where it states the novel is about the "destructive power of slavery and the ability of Christian love to overcome it…"

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The Complete Idiot's Guide to American Literature by Laurie E. Rozakis, Alpha Books, 1999, page 125, where it states that one of the book's main messages is that "The slavery crisis can only be resolved by Christian love."

- ↑ Domestic Abolitionism and Juvenile Literature, 1830–1865 by Deborah C. de Rosa, SUNY Press, 2003, page 121, where the book quotes Jane Tompkins on how Stowe's strategy with the novel was to destroy slavery through the "saving power of Christian love." This quote is from "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History" by Jane Tompkins, from In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Pp. 122–146. In that essay, Tompkins also states "Stowe conceived her book as an instrument for bringing about the day when the world would be ruled not by force, but by Christian love."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Sentimental Novel: The Example of Harriet Beecher Stowe" by Gail K. Smith, The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Women's Writing by Dale M. Bauer and Philip Gould, Cambridge University Press, 2001, page 221.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Introduction to Uncle Tom's Cabin Study Guide, BookRags.com, accessed May 16, 2006.

- ↑ Goldner, Ellen J. "Arguing with Pictures: Race, Class and the Formation of Popular Abolitionism Through Uncle Tom's Cabin." Journal of American & Comparative Cultures 2001 24(1–2): 71–84. Issn: 1537-4726 Fulltext: online at Ebsco.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Charles Edward Stowe, Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Story of Her Life (1911) p. 203.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hulser, Kathleen. "Reading Uncle Tom's Image: From Anti-slavery Hero to Racial Insult." New-York Journal of American History 2003 65(1): 75–79. Issn: 1551-5486.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Africana: arts and letters: an A-to-Z reference of writers, musicians, and artists of the African American Experience by Henry Louis Gates, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Running Press, 2005, page 544.

- ↑ Harriett Beecher Stowe's Life & Times. Harriet Beecher Stowe House and Library. Accessed Feb. 17, 2007.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Susan Logue, "Historic Uncle Tom's Cabin Saved", VOA News, January 12, 2006. Accessed May 16, 2006.

- ↑ Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin 1853, page 42, in which Stowe states "A last instance parallel with that of Uncle Tom is to be found in the published memoirs of the venerable Josiah Henson…" An excerpt of this information and acknowledgement is also in A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, pages 25–26.

- ↑ Weld, Theodore Dwight. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–2005. Accessed May 15, 2007.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 20, 2007.

- ↑ First Edition Illustrations, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Illustrations for the "Splendid Edition", Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 18, 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Slave narratives and Uncle Tom's Cabin, Africans in America, PBS, accessed Feb. 16, 2007.

- ↑ "publishing, history of." (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 18, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, page 31.

- ↑ Hagedorn, Ann. Beyond The River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. Simon & Schuster, 2002, pp. 135–139.

- ↑ The Word Detective, issue of May 20, 2003, accessed Feb. 16, 2007.

- ↑ Homelessness in American Literature: Romanticism, Realism, and Testimony by John Allen, Routledge, 2004, page 24, where it states in regards to Uncle Tom's Cabin that "Stowe held specific beliefs about the 'evils' of slavery and the role of Americans in resisting it." The book then quotes Ann Douglas describing how Stowe saw slavery as a sin.

- ↑ Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War by James Munro McPherson, Oxford University Press, 1997, page 30.

- ↑ Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Vintage Books, Modern Library Edition, 1991, page 150.

- ↑ Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War by James Munro McPherson, Oxford University Press, 1997, page 29.

- ↑ "Stowe's Dream of the Mother-Savior: Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Women Writers Before the 1920s" by Elizabeth Ammons, New Essays on Uncle Tom's Cabin, Eric J. Sundquist, editor, Cambridge University Press, 1986, page 159.

- ↑ Whitewashing Uncle Tom's Cabin: Nineteenth-Century Women Novelists Respond to Stowe by Joy Jordan-Lake, Vanderbilt University Press, 2005, page 61.

- ↑ Somatic Fictions: imagining illness in Victorian culture by Athena Vrettos, Stanford University Press, 1995, page 101.

- ↑ The Stowe Debate: Rhetorical Strategies in Uncle Tom's Cabin by Mason I. (jr.) Lowance, Ellen E. Westbrook, C. De Prospo, R., Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1994, page 132.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United States by Linda Eisenmann, Greenwood Press, 1998, page 3.

- ↑ The Company of the Creative: A Christian Reader's Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes by David L. Larsen, Kregel Publications, 2000, pages 386–387.

- ↑ The Company of the Creative: A Christian Reader's Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes by David L. Larsen, Kregel Publications, 2000, page 387.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of American Literature by Sacvan Bercovitch and Cyrus R. K. Patell, Cambridge University Press, 1994, page 119.

- ↑ Marianne Noble, "The Ecstasies of Sentimental Wounding In Uncle Tom's Cabin," from A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin Edited by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, page 58.

- ↑ "Domestic or Sentimental Fiction, 1820–1865" American Literature Sites, Washington State University, accessed April 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Uncle Tom's Cabin," The Kansas Territorial Experience, accessed April 26, 2007.

- ↑ Reading Women: Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Age to the Present by Janet Badia and Jennifer Phegley, University of Toronto Press, 2005, page 67.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Reading Women: Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Age to the Present by Janet Badia and Jennifer Phegley, University of Toronto Press, 2005, page 66.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, page 42.

- ↑ "Review of The Building of Uncle Tom's Cabin by E. Bruce Kirkham" by Thomas F. Gossett, American Literature, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Mar., 1978), pp. 123–124.

- ↑ "The Origins of Uncle Tom's Cabin" by Charles Nichols, The Phylon Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 (3rd Qtr., 1958), page 328.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History" by Jane Tompkins, from In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Pp. 122–146.

- ↑ "Introduction to Uncle Tom's Cabin" by Alyssa Harad, Cynthia Brantley Johnson, ereader.com, accessed April 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Stowe, Harriet Beecher." (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 18, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ "Simms's Review of Uncle Tom's Cabin" by Charles S. Watson, American Literature, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Nov., 1976), pp. 365–368

- ↑ "Over and above … There Broods a Portentous Shadow,—The Shadow of Law: Harriet Beecher Stowe's Critique of Slave Law in Uncle Tom's Cabin" by Alfred L. Brophy, Journal of Law and Religion, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1995–1996), pp. 457–506.

- ↑ "Woodcraft: Simms's First Answer to Uncle Tom's Cabin" by Joseph V. Ridgely, American Literature, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Jan., 1960), pp. 421–433.

- ↑ The Classic Text: Harriett Beecher Stowe. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Library. Special collection page on traditions and interpretations of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Accessed May 15, 2007.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Uncle Tom's Cabin, introduction by Amanda Claybaugh, Barnes and Noble Classics, New York, 2003, page xvii.

- ↑ Goldner, Ellen J. "Arguing with Pictures: Race, Class and the Formation of Popular Abolitionism Through Uncle Tom's Cabin." Journal of American & Comparative Cultures 2001 24(1–2): 71–84. Issn: 1537-4726 Fulltext: online at Ebsco.

- ↑ "Review of James Baird Weaver by Fred Emory Haynes" by A. M. Arnett, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar., 1920), pp. 154–157; and profile of James Baird Weaver, accessed Feb. 17, 2007.

- ↑ Nassau Senior, quoted in Ephraim Douglass Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War (1958) p: 33.

- ↑ Charles Francis Adams, Trans-Atlantic Historical Solidarity: Lectures Delivered before the University of Oxford in Easter and Trinity Terms, 1913. 1913. p. 79

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst, Economic History of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University Press, 1968), p. 122.

- ↑ Ian Gibson, The English Vice: Beating, Sex and Shame in Victorian England and After (1978)

- ↑ Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. See chapter five, "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History."

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe by Cindy Weinstein, Cambridge University Press, 2004, page 13.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Uncle Tom's Shadow" by Darryl Lorenzo Wellington, The Nation, December 25, 2006.

- ↑ "Review of The Building of Uncle Tom's Cabin by E. Bruce Kirkham" by Thomas F. Gossett, American Literature, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Mar., 1978), pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Smylie, James H. "Uncle Tom's Cabin Revisited: the Bible, the Romantic Imagination, and the Sympathies of Christ." American Presbyterians 1995 73(3): 165–175. Issn: 0886-5159.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Bellin, Joshua D. "Up to Heaven's Gate, down in Earth's Dust: the Politics of Judgment in Uncle Tom's Cabin" American Literature 1993 65(2): 275–295. Issn: 0002-9831 Fulltext online at Jstor and Ebsco.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Grant, David. "Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Triumph of Republican Rhetoric." New England Quarterly 1998 71(3): 429–448. Issn: 0028-4866 Fulltext online at Jstor.

- ↑ Riss, Arthur. "Racial Essentialism and Family Values in Uncle Tom's Cabin." American Quarterly 1994 46(4): 513–544. Issn: 0003-0678 Fulltext in JSTOR.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. "Masculinity in Uncle Tom's Cabin," American Quarterly 1995 47(4): 595–618. ISSN: 0003-0678. Fulltext online at JSTOR. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Wolff" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Smith; Jessie Carney; Images of Blacks in American Culture: A Reference Guide to Information Sources Greenwood Press. 1988.

- ↑ Illustrations, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Smith; Jessie Carney; Images of Blacks in American Culture: A Reference Guide to Information Sources Greenwood Press. 1988.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 "Digging Through the Literary Anthropology of Stowe’s Uncle Tom", by Edward Rothstein, from the New York Times, October 23, 2006.

- ↑ Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson by Linda Williams, Princeton Univ. Press, 2001, page 113.

- ↑ Whitewashing Uncle Tom's Cabin: nineteenth-century women novelists respond to Stowe by Joy Jordan-Lake, Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

- ↑ "Caroline Lee Hentz's Long Journey" by Philip D. Beidler. Alabama Heritage Number 75, Winter 2005.

- ↑ Figures in Black: words, signs, and the "racial" self by Henry Louis Gates, Oxford University Press, 1987, page 134.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "People & Events: Uncle Tom's Cabin Takes the Nation by Storm" Stephen Foster, The American Experience, PBS, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507832-2. The information on "Tom shows" comes from chapter 8: "Uncle Tomitudes: Racial Melodrama and Modes of Production" (p. 211–233)

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Africana: arts and letters: an A-to-Z reference of writers, musicians, and artists of the African American Experience by Henry Louis Gates, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Running Press, 2005, page 44.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Uncle Tom's Cabin on Film, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 The First Uncle Tom's Cabin Film: Edison-Porter's Slavery Days (1903), Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ The 3-Reel Vitagraph Production (1910), Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 hp.html Universal Super Jewel Production (1927), Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900–1942 by Thomas Cripps, Oxford University Press, 1993, page 48.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 Uncle Tom's Cabin in Hollywood: 1929–1956, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

- ↑ Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson by Linda Williams, Princeton Univ. Press, 2001, page 115. Also H. B. Stowe's Cabin in D. W. Griffith's Movie, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive, accessed April 19, 2007.

Bibliography

- Gates, Henry Louis; and Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Africana: Arts and Letters: an A-to-Z reference of writers, musicians, and artists of the African American Experience, Running Press, 2005.

- Jordan-Lake, Joy. Whitewashing Uncle Tom's Cabin: Nineteenth-Century Women Novelists Respond to Stowe, Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

- Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Lowance, Mason I. (jr.); Westbrook, Ellen E.; De Prospo, R., The Stowe Debate: Rhetorical Strategies in Uncle Tom's Cabin, Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

- Rosenthal, Debra J. Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin Routledge, 2003.

- Sundquist, Eric J., editor New Essays on Uncle Tom's Cabin, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Tompkins, Jane. In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford UP, 1985.

- Weinstein, Cindy. The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson, Princeton Univ. Press, 2001.

Online resources

- University of Virginia Web site "Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture: A Multi-Media Archive" Ed by Stephen Railton, covers 1830 to 1930, offering links to primary and bibliographic sources on the cultural background, various editions, and public reception of Harriet Beecher Stowe's influential novel. The site also provides the full text of the book, audio and video clips, and examples of related merchandising.

External links

- Uncle Tom's cabin: or Life among the lowly; frontispiece by John Gilbert; ornamental title-page by Phiz; and 130 engravings on wood by Matthew Urlwin Sears, 1853 (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Pictures and stories from Uncle Tom's cabin; "The purpose of the editor of this little work, has been to adapt it for the juvenile family circle. The verses have accordingly been written by the authoress for the capacity of the youngest readers …" 1853 (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Uncle Tom's Cabin, available for free via Project Gutenberg

- Uncle Tom's Cabin, available at Internet Archive. Scanned, illustrated original editions.

- Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site

- Free audiobook of Uncle Tom's Cabin at Librivox

- More on the lack of international copyright

Template:American Civil War

ar:كوخ العم توم bn:আঙ্কল টমস্ কেবিন bg:Чичо Томовата колиба cy:Caban F'ewyrth Twm da:Onkel Toms Hytte de:Onkel Toms Hütte el:Η Καλύβα του Μπαρμπα-Θωμά es:La cabaña del tío Tom eo:La Kabano de Onklo Tom fa:کلبه عمو تام fr:La Case de l'oncle Tom ko:톰 아저씨의 오두막 hr:Čiča Tomina koliba id:Pondok Paman Tom it:La capanna dello zio Tom he:אוהל הדוד תום lv:Krusttēva Toma būda nl:De negerhut van Oom Tom ja:アンクル・トムの小屋 no:Onkel Toms hytte pl:Chata wuja Toma pt:Uncle Tom's Cabin ru:Хижина дяди Тома fi:Setä Tuomon tupa sv:Onkel Toms stuga th:กระท่อมน้อยของลุงทอม vi:Túp lều bác Tôm zh:汤姆叔叔的小屋

Partial list of works

- Uncle Tom's Cabin (1851) ISBN 0679602003

- A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853) ISBN 1557094934

- Dred, A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856) ISBN 0807856851

- The Minister's Wooing (1859) ISBN 1418105198

- The Pearl of Orr's Island (1862) ISBN 040300280X

- As "Christopher Crowfield"

- House and Home Papers (1865) ISBN 1417947543

- Little Foxes (1866)

- The Chimney Corner (1868)

- Old Town Folks (1869)

- The Ghost in the Cap'n Brown (1870)

- Lady Byron Vindicated (1870) ISBN 1414257287

- My Wife and I (1871) ISBN 1591070570

- Pink and White Tyranny (1871) ISBN 155709960X

- We and Our Neighbors (1875) ISBN 1591070481

- Poganuc People (1878) ISBN 1419142437

References and further reading

- Adams, John R. Harriet Beecher Stowe. Twayne Publishers, 1963., ISBN 0808401505

- Hedrick, Joan. Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Life. Oxford University Press, USA, 1995.

- Margolis, Anne, Jeanne Boydston, and Mary Kelley. The Limits of Sisterhood: The Beecher Sisters on Women's Rights and Woman's Sphere. University of North Carolina Press, 1988. ISBN 0807842079

- Matthews, Glenna. "'Little Women' Who Helped Make This Great War" in Gabor S. Boritt, ed. Why the Civil War Came. Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0195113764

- Rourke, Constance Mayfield. Trumpets of Jubilee: Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lyman Beecher, Horace Greeley, P.T. Barnum. (1927).

- Thulesius, Olav. Harriet Beecher Stowe in Florida, 1867-1884. McFarland and Company, 2001. ISBN 0786409320

- Weinstein, Cindy. The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Cambridge Companions to Literature (Cctl). Cambridge, England: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004. ISBN 0521533090

- White, Barbara A. The Beecher Sisters. Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300099274

External links

- Harriet Beecher Stowe House & Center - Stowe's adulthood home in Hartford, Connecticut

- Harriet Beecher Stowe Society—Scholarly organization dedicated to the study of the life and works of Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Brief biography at Kirjasto (Pegasos)

- An American Family: The Beechers

- Harriet Beecher Stowe Quotes

- Beecher-Stowe Family Papers

- The Online Books Page (University of Pennsylvania)

- Works by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Project Gutenberg

- Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe Compiled From Her Letters and Journals by Her Son Charles Edward Stowe, available for free via Project Gutenberg

- Harriet Beecher Stowe Bibliography

- Harriet Beecher Stowe's brief biography and works

- Women in History

- Lady Byron Vindicated

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.