Difference between revisions of "Gilgamesh, Epic of" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (Added categories) |

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | The '''''Epic of Gilgamesh''''' is an [[epic poetry|epic poem]] from [[Babylonia]] and is arguably the oldest known work of [[literature]]. A series of [[Sumerian legends]] and poems about the mythologized hero-king [[Gilgamesh]], thought to be a ruler of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., were gathered into a longer [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] [[poem]] long afterward, with the most complete version extant today preserved on eleven clay tablets in the library collection of the 7th century B.C.E. [[Assyria]]n king [[Ashurbanipal]]. | ||

| + | The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times, and to have influenced literature from India to Europe{{fact}}. One of the stories included in the epic relates to the [[deluge (mythology)|deluge]]. The essential story revolves around the relationship between Gilgamesh, a king who has become distracted and disheartened by his rule, and a friend, [[Enkidu]], who is half-wild and who undertakes dangerous quests with Gilgamesh. Much of the epic focuses on Gilgamesh's feelings of loss following Enkidu's death. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The epic is widely read in translation, and the hero, Gilgamesh has become an [[Gilgamesh in popular culture|icon of popular culture]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History== | ||

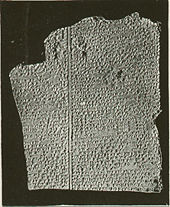

| + | [[image:GilgameshTablet.jpg|left|thumb|170px|The [[deluge (mythology)|Deluge]] tablet of the Gilgamesh epic in [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]]]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Gilgamesh''', according to the [[Sumerian king list]], was the fifth king of [[Uruk]] (Early Dynastic II, first dynasty of Uruk), the son of [[Lugalbanda]], ruling circa 2650 B.C.E. Legend has it that his mother was [[Ninsun]], a goddess. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to another document, known as the "History of Tummal", Gilgamesh, and eventually his son Urlugal, rebuilt the sanctuary of the goddess [[Ninlil]], located in Tummal, a block of the [[Nippur]] city. In [[Mesopotamian]] mythology Gilgamesh is credited to have been a demi-god of superhuman strength, a mythological equivalent to [[Hercules]], who built a great wall in Iraq to defend his people from outer harm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Gilgamesh]]'s supposed historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2500 B.C.E., 400 years prior to the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with Agga and [[Enmebaragesi]] of [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]], two other kings named in the stories, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.{{fact}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The earliest [[Sumer]]ian versions of the epic date from as early as the [[Third dynasty of Ur]] (2100 B.C.E.-2000 B.C.E.). {{fact}} The earliest [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] versions are dated to ca. 2000-1500 B.C.E. {{fact}} The "standard" Akkadian version, composed by [[Sin-liqe-unninni]] was composed sometime between 1300 B.C.E. and 1000 B.C.E. The standard and earlier Akkadian versions are differentiated based on the opening words, or [[incipit]]. The older version begins with the words "Surpassing all other kings", while the standard version's ''incipit'' is "He who saw the deep" (''ša nagbu amāru''). The Akkadian word ''nagbu'', "deep", is probably to be interpreted here as referring to "unknown mysteries".{{fact}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The eleventh (XI) tablet contains the flood myth that was mostly copied from the Epic of [[Atrahasis]]. See [[Gilgamesh flood myth]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | A twelfth tablet sometimes appended to the remainder of the epic represents a sequel to the original eleven, and was added at a later date. This tablet has commonly been omitted until recent years, as it is in a different style and is out of sequence with the rest of the tablets ("[[Enkidu]] is still alive..."), and is considered a separate work<ref>[http://www.mythome.org/gilgamesh12.html MythHome: Gilgamesh the 12th Tablet]</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' is widely known today. The first modern translation of the epic was in the 1870s by [[George Smith (Assyriologist)|George Smith]].{{fact}} More recent translations include one undertaken with the assistance of the American novelist John Gardner, and published in 1984. Another edition is the two volume critical work by Andrew George whose translation also appeared in the Penguin Classics series in 2003. In 2004, Stephen Mitchell released a controversial edition, which is his interpretation of previous scholarly translations into what he calls the "New English version".{{fact}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Cuneiform references== | ||

| + | In the ''[[Epic of Gilgamesh]]'' it is said that Gilgamesh ordered the creation of the legendary walls of [[Uruk]]. In historical times, [[Sargon of Akkad]] claimed to have destroyed these walls to prove his military power. Many scholars feel that the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' is related to the Biblical story of the flood mentioned in Genesis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fragments of an epic text found in Me-Turan (modern Tell Haddad) relate that Gilgamesh was buried under the waters of a river at the end of his life. The people of Uruk diverted the flow of the [[Euphrates]] River crossing Uruk for the purpose of burying the dead king within the riverbed. In April [[2003]], a [[Germany|German]] expedition discovered what is thought to be the entire city of Uruk - including, where the Euphrates once flowed, the last resting place of its King Gilgamesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the lack of direct evidence, most scholars do not object to consideration of Gilgamesh as a historical figure, particularly after inscriptions were found confirming the historical existence of other figures associated with him: kings [[Enmebaragesi]] and Aga of [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]]. If Gilgamesh was a historical king, he probably reigned in about the [[26th century B.C.E.]]. Some of the earliest Sumerian texts spell his name as ''Bilgamesh''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In most texts, Gilgamesh is written with the determinative for divine beings (''DINGIR'') - but there is no evidence for a contemporary cult, and the [[Sumer]]ian Gilgamesh myths suggest the deification was a later development (unlike the case of the [[Akkad]]ian god-kings). Historical or not, Gilgamesh became a legendary protagonist in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Influence on later Epic Literature == | ||

| + | According to the Greek scholar [[Ioannis Kordatos]], there are a large number of parallel verses as well as themes or episodes which indicate a substantial influence of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' on the ''[[Odyssey]]'', the Greek epic poem ascribed to [[Homer]].<ref>[[Ioannis Kakridis]]: "Eisagogi eis to Omiriko Zitima" (Introduction to the Homeric Question) In: Omiros: Odysseia. Edited with translation and comments by Zisimos Sideris, Daidalos Press, I. Zacharopoulos Athens. See [[Odyssey]] article for more details.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some aspects of the epic also seem to be related to the story of [[Noah's ark]] in the [[Bible]], and also parallel flood stories in many other cultures around the world, although it is a complicated matter to say what is the original inspiration for any of these, on which modern commentators have always been divided.{{fact}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Contents of the eleven clay tablets== | ||

| + | [[Image:Gilgamesh Enkidu cylinder seal.jpg|thumb|250px|Gilgamesh and Enkidu on a [[Cylinder seal|cylinder seal]] from [[Ur]] III]] | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh of [[Uruk]], the greatest king on earth, two-thirds god and one-third human, is the strongest super-human who ever existed. When his people complain that he is too harsh the sky-god [[Anu]] creates the wild-man [[Enkidu]], a worthy rival as well as distraction. Enkidu is tamed by the seduction of priestess (a [[hierodule]]) [[Shamhat]]. | ||

| + | #Enkidu challenges Gilgamesh. After a mighty battle, Gilgamesh breaks off from the fight (this portion is missing from the Standard Babylonian version but is supplied from other versions). Gilgamesh proposes an adventure in the [[Cedar Forest]] to kill a [[demon]]. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh and Enkidu prepare to adventure to the Cedar Forest, with support from many including the sun-god [[Shamash]]. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey to the Cedar Forest. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh and Enkidu, with help from Shamash, kill [[Humbaba]], the demon guardian of the trees, then cut down the trees which they float as a raft back to Uruk. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh rejects the sexual advances of Anu's daughter, the goddess [[Ishtar]]. Ishtar asks her father to send the "[[Bull of Heaven]]" to avenge the rejected sexual advances. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the bull. | ||

| + | #The gods decide that somebody has to be punished for killing the Bull of Heaven, and they condemn Enkidu. Enkidu becomes ill and describes the [[Netherworld]] as he is dying. [[Stephen Mitchell]] and others interpret the punishment as being for the killing of [[Humbaba]], as it was ordered to guard the Cedar Forest by the gods. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh delivers a lamentation for Enkidu. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh sets out to avoid Enkidu's fate and makes a perilous journey to visit [[Utnapishtim]] and his wife, the only humans to have survived the [[Deluge (mythology)|Great Flood]] who were granted immortality by the gods, in the hope that he too can attain immortality. Along the way, Gilgamesh encounters the [[alewyfe]] [[Siduri]] who attempts to dissuade him from his quest. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh [[punt (boat)|punts]] across the [[Waters of Death]] with [[Urshanabi]], the ferryman, completing the journey. | ||

| + | #Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim, who tells him about the great flood and reluctantly gives him a chance for immortality. He tells Gilgamesh that if he can stay awake for six days and seven nights he will become immortal. However, Gilgamesh falls asleep and Utnapishtim tells his wife to bake a loaf of bread for every day he is asleep so that Gilgamesh cannot deny his failure. When Gilgamesh wakes up, Utnapishtim decides to tell him about a plant that will rejuvenate him. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh that if he can obtain the plant from the bottom of the sea and eat it he will be rejuvenated, be a younger man again. Gilgamesh obtains the plant, but doesn't eat it immediately because he wants to share it with other elders of Uruk. He places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes and it is stolen by a snake. Gilgamesh, having failed both chances, returns to Uruk, where the sight of its massive walls provokes him to praise this enduring work of mortal men. Gilgamesh realizes that the way mortals can achieve immortality is through lasting works of civilization and culture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The ''Epic'' in other media== | ||

| + | [[Image:Mitchell Gilgamesh-05.jpg|thumb|300px|Extract from ''Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh'', a comic adaptation of one man's personal discovery of the epic text. The panels depict the wrestling match between Gilgamesh and [[Enkidu]].]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The Czech composer [[Bohuslav Martinů]] wrote ''The Epic of Gilgamesh'' for choir and orchestra in 1955: he described it as "neither a [[cantata]] nor an [[oratorio]], simply an Epic". The story was brought to his attention by his wife Maja in 1948 when she showed him a booklet from the [[British Museum]] about the clay tablets, and he used a translation of the poem by [[Reginald Campbell]] as the basis for the [[libretto]], which is in the [[Czech (language)|Czech]] and which reinterprets Gilgamesh as [[Everyman]]. The 53 minute long work was commissioned by [[Paul Sacher]] who conducted its premiere in Basel, [[Switzerland]] in 1958. | ||

| + | *Gilgamesh was mentioned in ''[[The Outer Limits]]'' television series episode ''[[Demon with a Glass Hand]]'', first broadcast in [[1964]] and written by [[Harlan Ellison]]. | ||

| + | *The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' is quoted directly in an episode of the American television series ''Star Trek: The Next Generation''. The episode ''[[Darmok]]'' (1991) quotes the Epic as an example of the use of metaphorical language and the difficulties of communication and understanding. The characters of [[Jean-Luc Picard|Picard]] and [[Darmok|Dathon]] at El-Ardel can be interpreted as latter-day examples of Gilgamesh and Enkidu at [[Uruk]]. | ||

| + | *''[[Gilgamesh II]]'' was a four issue mature readers mini-series published by [[DC Comics]] in 1989. | ||

| + | *[[Mage (comics)|Mage]] has a retelling of the epic in the second volume of the trilogy, with Kevin Matchstick and Kirby Hero standing in for Gilgamesh and Enkidu. | ||

| + | *In an episode of the American television series [[Lost (TV series)|Lost]], the character Locke is seen solving a crossword puzzle and one of the clues is "Enkidu's friend". He writes down the answer Gilgamesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | *http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MESO/GILG.HTM | ||

| + | *[http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/mideast/mi-wtst.htm The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography] | ||

| + | *Babylonian (Akkadian) texts: [http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=c.1.8.1* ETCSL] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1815.htm Gilgamesh and Huwawa], version A - (the adventure of the cedar forest) | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr18151.htm Gilgamesh and Huwawa], version B | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1812.htm Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1811.htm Gilgamesh and Aga] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1814.htm Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the nether world] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1813.htm The death of Gilgamesh] | ||

| + | *[http://www.noahs-ark-flood.com/parallels.htm Comparison of equivalent lines in six ancient versions of the flood story] | ||

| + | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/noah_com.htm Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood] | ||

| + | *[http://www.christian-thinktank.com/gilgy09.html Comparison of the Flood in Genesis to the Epic of Gilgamesh and related literature] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Translations for several legends of Gilgamesh in the [[Sumerian language]] can be found in Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., ''The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature'' ([http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/ http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/]), Oxford 1998-. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Bibliography== | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=George, Andrew R., trans. & edit. | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location= | publisher=Penguin Books| year=2000, reprinted with corrections 2003 | id=ISBN 0140449191}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Foster, Benjamin R., trans. & edit. | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=New York | publisher=W.W. Norton & Company | year=2001 | id=ISBN 0-393-97516-9}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=Stanford University Press | publisher=Stanford, California | year=1985,1989 | id=ISBN 0-8047-1711-7}} Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI). | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Jackson, Danny | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=Wauconda, IL | publisher=Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers | year=1997 | id=ISBN 0-86516-352-9}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Mitchell, Stephen | title=Gilgamesh: A New English Version | location=New York | publisher=Free Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-7432-6164-X}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=[[Simo Parpola|Parpola, Simo]], with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius | title=The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh | publisher=The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project | year=1997 | id=ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1) in the original Akkadian cuneiform and transliteration; commentary and glossary are in English }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Chaldean mythology]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Bibliography== | ||

| + | *Cooper, Jerrold S. [2002], "Buddies in Babylonia - Gilgamesh, Enkidu and Mesopotamian Homosexuality", in Abusch, Tz (ed.), ''Riches Hidden in Secret Places - Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen'', Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2002, pp.73-85. | ||

| + | *George, Andrew [1999], ''The Epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian'', Harmondsworth: Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 1999 (published in Penguin Classics 2000, reprinted with minor revisions, 2003. ISBN 0140449191 | ||

| + | *George, Andrew, ''The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic - Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2 volumes, 2003. | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Foster, Benjamin R., trans. & edit. | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=New York | publisher=W.W. Norton & Company | year=2001 | id=ISBN 0-393-97516-9}} | ||

| + | *Hammond, D. & Jablow, A. [1987], "Gilgamesh and the Sundance Kid: the Myth of Male Friendship", in Brod, H. (ed.), ''The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies'', Boston, 1987, pp.241-258. | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=Stanford University Press | publisher=Stanford, California | year=1985,1989 | id=ISBN 0-8047-1711-7}} Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). '''A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI).''' | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Jackson, Danny | title=The Epic of Gilgamesh | location=Wauconda, IL | publisher=Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers | year=1997 | id=ISBN 0-86516-352-9}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Mitchell, Stephen | title=Gilgamesh: A New English Version | location=New York | publisher=Free Press | year=2004 | id=ISBN 0-7432-6164-X}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius | title=The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh | publisher=The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project | year=1997 | id=ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1) }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Text translations=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Mitchell Gilgamesh-05.jpg|thumb|300px|Extract from ''Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh'', a comic adaptation of one man's personal discovery of the epic text. The panels depict the wrestling match between Gilgamesh and [[Enkidu]].]] | ||

| + | {{wikisourcelang|en|The Epic of Gilgamesh|The Epic of Gilgamesh}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | *http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MESO/GILG.HTM | ||

| + | *[http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/mideast/mi-wtst.htm The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography] | ||

| + | *Sumerian texts: [http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=c.1.8.1* ETCSL] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1815.htm Gilgamesh and Huwawa], version A - (the adventure of the cedar forest) | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr18151.htm Gilgamesh and Huwawa], version B | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1812.htm Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1811.htm Gilgamesh and Aga] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1814.htm Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the nether world] | ||

| + | **[http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1813.htm The death of Gilgamesh] | ||

| + | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/noah_com.htm Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood] | ||

| + | *''The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature'' ([http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/ http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/]), Oxford 1998-. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Translations for several legends of Gilgamesh in the [[Sumerian language]] have been written by: | ||

| + | *Black, J.A., | ||

| + | *Cunningham, G., | ||

| + | *Fluckiger-Hawker, E, | ||

| + | *[[Stephen Mitchell]] | ||

| + | **[http://www.strippedbooks.com/comics/stripped03/gilgamesh01.html Stripped Books: Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh] - a comic-book adaptation of a talk by Stephen Mitchell about the epic poem. | ||

| + | **Mitchell's translation was also adapted as a [[radio play]] for [[Radio 3]] by [[Jeremy Howe]], first broadcast on Sunday 11 June 2006 from 19:30-21:30 [http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/dramaon3/pip/gci75/] | ||

| + | *Robson, E., | ||

| + | *Zólyomi, G., | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Other links=== | ||

| + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2982891.stm "Gilgamesh tomb believed found"] - [[BBC News Online]] article, 29 April 2004. | ||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] [[Category: Religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] [[Category: Religion]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Credit2|Epic_of_Gilgamesh|66821911|Gilgamesh|66718617}} | ||

Revision as of 21:23, 1 August 2006

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from Babylonia and is arguably the oldest known work of literature. A series of Sumerian legends and poems about the mythologized hero-king Gilgamesh, thought to be a ruler of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., were gathered into a longer Akkadian poem long afterward, with the most complete version extant today preserved on eleven clay tablets in the library collection of the 7th century B.C.E. Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times, and to have influenced literature from India to Europe[citation needed]. One of the stories included in the epic relates to the deluge. The essential story revolves around the relationship between Gilgamesh, a king who has become distracted and disheartened by his rule, and a friend, Enkidu, who is half-wild and who undertakes dangerous quests with Gilgamesh. Much of the epic focuses on Gilgamesh's feelings of loss following Enkidu's death.

The epic is widely read in translation, and the hero, Gilgamesh has become an icon of popular culture.

History

Gilgamesh, according to the Sumerian king list, was the fifth king of Uruk (Early Dynastic II, first dynasty of Uruk), the son of Lugalbanda, ruling circa 2650 B.C.E. Legend has it that his mother was Ninsun, a goddess.

According to another document, known as the "History of Tummal", Gilgamesh, and eventually his son Urlugal, rebuilt the sanctuary of the goddess Ninlil, located in Tummal, a block of the Nippur city. In Mesopotamian mythology Gilgamesh is credited to have been a demi-god of superhuman strength, a mythological equivalent to Hercules, who built a great wall in Iraq to defend his people from outer harm.

Gilgamesh's supposed historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2500 B.C.E., 400 years prior to the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with Agga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, two other kings named in the stories, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.[citation needed]

The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic date from as early as the Third dynasty of Ur (2100 B.C.E.-2000 B.C.E.). [citation needed] The earliest Akkadian versions are dated to ca. 2000-1500 B.C.E. [citation needed] The "standard" Akkadian version, composed by Sin-liqe-unninni was composed sometime between 1300 B.C.E. and 1000 B.C.E. The standard and earlier Akkadian versions are differentiated based on the opening words, or incipit. The older version begins with the words "Surpassing all other kings", while the standard version's incipit is "He who saw the deep" (ša nagbu amāru). The Akkadian word nagbu, "deep", is probably to be interpreted here as referring to "unknown mysteries".[citation needed]

The eleventh (XI) tablet contains the flood myth that was mostly copied from the Epic of Atrahasis. See Gilgamesh flood myth

A twelfth tablet sometimes appended to the remainder of the epic represents a sequel to the original eleven, and was added at a later date. This tablet has commonly been omitted until recent years, as it is in a different style and is out of sequence with the rest of the tablets ("Enkidu is still alive..."), and is considered a separate work[1].

The Epic of Gilgamesh is widely known today. The first modern translation of the epic was in the 1870s by George Smith.[citation needed] More recent translations include one undertaken with the assistance of the American novelist John Gardner, and published in 1984. Another edition is the two volume critical work by Andrew George whose translation also appeared in the Penguin Classics series in 2003. In 2004, Stephen Mitchell released a controversial edition, which is his interpretation of previous scholarly translations into what he calls the "New English version".[citation needed]

Cuneiform references

In the Epic of Gilgamesh it is said that Gilgamesh ordered the creation of the legendary walls of Uruk. In historical times, Sargon of Akkad claimed to have destroyed these walls to prove his military power. Many scholars feel that the Epic of Gilgamesh is related to the Biblical story of the flood mentioned in Genesis.

Fragments of an epic text found in Me-Turan (modern Tell Haddad) relate that Gilgamesh was buried under the waters of a river at the end of his life. The people of Uruk diverted the flow of the Euphrates River crossing Uruk for the purpose of burying the dead king within the riverbed. In April 2003, a German expedition discovered what is thought to be the entire city of Uruk - including, where the Euphrates once flowed, the last resting place of its King Gilgamesh.

Despite the lack of direct evidence, most scholars do not object to consideration of Gilgamesh as a historical figure, particularly after inscriptions were found confirming the historical existence of other figures associated with him: kings Enmebaragesi and Aga of Kish. If Gilgamesh was a historical king, he probably reigned in about the 26th century B.C.E. Some of the earliest Sumerian texts spell his name as Bilgamesh.

In most texts, Gilgamesh is written with the determinative for divine beings (DINGIR) - but there is no evidence for a contemporary cult, and the Sumerian Gilgamesh myths suggest the deification was a later development (unlike the case of the Akkadian god-kings). Historical or not, Gilgamesh became a legendary protagonist in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Influence on later Epic Literature

According to the Greek scholar Ioannis Kordatos, there are a large number of parallel verses as well as themes or episodes which indicate a substantial influence of the Epic of Gilgamesh on the Odyssey, the Greek epic poem ascribed to Homer.[2]

Some aspects of the epic also seem to be related to the story of Noah's ark in the Bible, and also parallel flood stories in many other cultures around the world, although it is a complicated matter to say what is the original inspiration for any of these, on which modern commentators have always been divided.[citation needed]

Contents of the eleven clay tablets

- Gilgamesh of Uruk, the greatest king on earth, two-thirds god and one-third human, is the strongest super-human who ever existed. When his people complain that he is too harsh the sky-god Anu creates the wild-man Enkidu, a worthy rival as well as distraction. Enkidu is tamed by the seduction of priestess (a hierodule) Shamhat.

- Enkidu challenges Gilgamesh. After a mighty battle, Gilgamesh breaks off from the fight (this portion is missing from the Standard Babylonian version but is supplied from other versions). Gilgamesh proposes an adventure in the Cedar Forest to kill a demon.

- Gilgamesh and Enkidu prepare to adventure to the Cedar Forest, with support from many including the sun-god Shamash.

- Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey to the Cedar Forest.

- Gilgamesh and Enkidu, with help from Shamash, kill Humbaba, the demon guardian of the trees, then cut down the trees which they float as a raft back to Uruk.

- Gilgamesh rejects the sexual advances of Anu's daughter, the goddess Ishtar. Ishtar asks her father to send the "Bull of Heaven" to avenge the rejected sexual advances. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the bull.

- The gods decide that somebody has to be punished for killing the Bull of Heaven, and they condemn Enkidu. Enkidu becomes ill and describes the Netherworld as he is dying. Stephen Mitchell and others interpret the punishment as being for the killing of Humbaba, as it was ordered to guard the Cedar Forest by the gods.

- Gilgamesh delivers a lamentation for Enkidu.

- Gilgamesh sets out to avoid Enkidu's fate and makes a perilous journey to visit Utnapishtim and his wife, the only humans to have survived the Great Flood who were granted immortality by the gods, in the hope that he too can attain immortality. Along the way, Gilgamesh encounters the alewyfe Siduri who attempts to dissuade him from his quest.

- Gilgamesh punts across the Waters of Death with Urshanabi, the ferryman, completing the journey.

- Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim, who tells him about the great flood and reluctantly gives him a chance for immortality. He tells Gilgamesh that if he can stay awake for six days and seven nights he will become immortal. However, Gilgamesh falls asleep and Utnapishtim tells his wife to bake a loaf of bread for every day he is asleep so that Gilgamesh cannot deny his failure. When Gilgamesh wakes up, Utnapishtim decides to tell him about a plant that will rejuvenate him. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh that if he can obtain the plant from the bottom of the sea and eat it he will be rejuvenated, be a younger man again. Gilgamesh obtains the plant, but doesn't eat it immediately because he wants to share it with other elders of Uruk. He places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes and it is stolen by a snake. Gilgamesh, having failed both chances, returns to Uruk, where the sight of its massive walls provokes him to praise this enduring work of mortal men. Gilgamesh realizes that the way mortals can achieve immortality is through lasting works of civilization and culture.

The Epic in other media

- The Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů wrote The Epic of Gilgamesh for choir and orchestra in 1955: he described it as "neither a cantata nor an oratorio, simply an Epic". The story was brought to his attention by his wife Maja in 1948 when she showed him a booklet from the British Museum about the clay tablets, and he used a translation of the poem by Reginald Campbell as the basis for the libretto, which is in the Czech and which reinterprets Gilgamesh as Everyman. The 53 minute long work was commissioned by Paul Sacher who conducted its premiere in Basel, Switzerland in 1958.

- Gilgamesh was mentioned in The Outer Limits television series episode Demon with a Glass Hand, first broadcast in 1964 and written by Harlan Ellison.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh is quoted directly in an episode of the American television series Star Trek: The Next Generation. The episode Darmok (1991) quotes the Epic as an example of the use of metaphorical language and the difficulties of communication and understanding. The characters of Picard and Dathon at El-Ardel can be interpreted as latter-day examples of Gilgamesh and Enkidu at Uruk.

- Gilgamesh II was a four issue mature readers mini-series published by DC Comics in 1989.

- Mage has a retelling of the epic in the second volume of the trilogy, with Kevin Matchstick and Kirby Hero standing in for Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

- In an episode of the American television series Lost, the character Locke is seen solving a crossword puzzle and one of the clues is "Enkidu's friend". He writes down the answer Gilgamesh.

External links

- http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MESO/GILG.HTM

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography

- Babylonian (Akkadian) texts: ETCSL

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version A - (the adventure of the cedar forest)

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version B

- Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven

- Gilgamesh and Aga

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the nether world

- The death of Gilgamesh

- Comparison of equivalent lines in six ancient versions of the flood story

- Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood

- Comparison of the Flood in Genesis to the Epic of Gilgamesh and related literature

Translations for several legends of Gilgamesh in the Sumerian language can be found in Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford 1998-.

Bibliography

- George, Andrew R., trans. & edit. (2000, reprinted with corrections 2003). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140449191.

- Foster, Benjamin R., trans. & edit. (2001). The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97516-9.

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. (1985,1989). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Stanford University Press: Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-1711-7. Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI).

- Jackson, Danny (1997). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-352-9.

- Mitchell, Stephen (2004). Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-6164-X.

- Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius (1997). The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1) in the original Akkadian cuneiform and transliteration; commentary and glossary are in English.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ MythHome: Gilgamesh the 12th Tablet

- ↑ Ioannis Kakridis: "Eisagogi eis to Omiriko Zitima" (Introduction to the Homeric Question) In: Omiros: Odysseia. Edited with translation and comments by Zisimos Sideris, Daidalos Press, I. Zacharopoulos Athens. See Odyssey article for more details.

See also

- Chaldean mythology

Bibliography

- Cooper, Jerrold S. [2002], "Buddies in Babylonia - Gilgamesh, Enkidu and Mesopotamian Homosexuality", in Abusch, Tz (ed.), Riches Hidden in Secret Places - Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2002, pp.73-85.

- George, Andrew [1999], The Epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, Harmondsworth: Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 1999 (published in Penguin Classics 2000, reprinted with minor revisions, 2003. ISBN 0140449191

- George, Andrew, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic - Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2 volumes, 2003.

- Foster, Benjamin R., trans. & edit. (2001). The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97516-9.

- Hammond, D. & Jablow, A. [1987], "Gilgamesh and the Sundance Kid: the Myth of Male Friendship", in Brod, H. (ed.), The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies, Boston, 1987, pp.241-258.

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. (1985,1989). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Stanford University Press: Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-1711-7. Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI).

- Jackson, Danny (1997). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-352-9.

- Mitchell, Stephen (2004). Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-6164-X.

- Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius (1997). The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1).

External links

Text translations

- http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MESO/GILG.HTM

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography

- Sumerian texts: ETCSL

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version A - (the adventure of the cedar forest)

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa, version B

- Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven

- Gilgamesh and Aga

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the nether world

- The death of Gilgamesh

- Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford 1998-.

Translations for several legends of Gilgamesh in the Sumerian language have been written by:

- Black, J.A.,

- Cunningham, G.,

- Fluckiger-Hawker, E,

- Stephen Mitchell

- Stripped Books: Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh - a comic-book adaptation of a talk by Stephen Mitchell about the epic poem.

- Mitchell's translation was also adapted as a radio play for Radio 3 by Jeremy Howe, first broadcast on Sunday 11 June 2006 from 19:30-21:30 [1]

- Robson, E.,

- Zólyomi, G.,

Other links

- "Gilgamesh tomb believed found" - BBC News Online article, 29 April 2004.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.