Difference between revisions of "Gilgamesh, Epic of" - New World Encyclopedia

m ({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (55 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} |

| − | The '''''Epic of Gilgamesh''''' is an | + | [[Category:Public]] |

| + | The '''''Epic of Gilgamesh''''' is an epic poem from [[Babylonia]] and arguably the oldest known work of literature. The story includes a series of legends and poems integrated into a longer [[Akkadian Empire|Akkadian]] epic about the hero-king Gilgamesh of Uruk (Erech, in the Bible), a ruler of the third millennium <small>B.C.E.</small> Several versions have survived, the most complete being preserved on eleven clay tablets in the library of the seventh-century <small>B.C.E.</small> Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. | ||

| − | The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times | + | The essential story tells of the spiritual maturation of the heroic Gilgamesh, the powerful but self-centered king who tyrannizes his people and even disregards the gods. He is part divine and part human. Through his adventures, Gilgamesh first begins to know himself through experiencing the death of his only friend, Enkidu. Seeking the secret of eternal life, he travels on the archetypal hero's journey, ultimately returning to Uruk a much wiser man than when he left and reconciled to his mortality. |

| + | {{readout||right|250px|One of the stories in the Gilgamesh epic directly parallels the story of [[Noah]]'s [[Great Flood]]}} | ||

| + | The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times and to have influenced important works of literature, from the book of [[Genesis]] to ''The [[Odyssey]]''. One of the stories included in the epic directly parallels the story of [[Great Flood|Noah's flood]]. | ||

| − | + | Episodes in Gilgamesh foreshadow many other later stories in both Biblical and secular literature: | |

| − | == | + | * The Fall of Man (the naked savage Enkidu's harmony with nature is broken when he is seduced by the prostitute Shamhat, who initiates him to "knowledge of good and evil," and makes him aware that he is naked and ashamed, at which point she clothes him) |

| − | [[ | + | * David and Jonathan (Enkidu's sacrificial loyalty for his rival, Gilgamesh) |

| + | * The Fruit of the Tree of Life (the plant of eternal youth stolen by a serpent) | ||

| + | * Hercules (Gilgamesh as the nearly immortal demi-god and great, but flawed, hero) | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Even with its missing lines and far from seamless narrative style, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a work of great literature, made all the more wonderful because it predates all others. It is widely read in translation, and its hero has become a minor icon of popular culture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Summary== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following is a summary of each of the tablets from the Epic of Gilgamesh:<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20021001233621/http://www.unf.edu/classes/freshmancore/halsall/gilgamesh-kovacs.htm#Tablet%20I Tablet One:] The Epic of Gilgamesh Translated by Maureen Gallery Kovacs. Retrieved September 19, 2016.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | * '''Tablet 1''': A narrator invites the reader to view the majesty of the city of Uruk and introduces us to its king, Gilgamesh. He is the greatest king on [[Earth]], two-thirds [[god]] and one-third [[human being|human]], the strongest man who ever existed. Yet he reigns as a tyrant over his people in the city of Uruk, failing to sympathize with their plight and even exercising the supposed right to deflower brides before their husbands sleep with them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When his people complain to the gods that he is too harsh, the gods decide to educate Gilgamesh. The mother goddess Aruru/Ninhursag creates the hairy wild-man Enkidu as a worthy rival. Enkidu lives wild among the gazelles of the forest. Enkidu destroys the traps of a trapper, who discovers him and requests that Gilgamesh send a temple-harlot to ensnare the wild man so the wild beasts will then reject him. Gilgamesh sends Shamhat, the sacred harlot of the goddess [[Ishtar]], who seduces Enkidu into a week-long sexual initiation, in which Enkidu demonstrates unmatched virility. As a result of this encounter, the animals now fear him and flee his presence. Bereft, Enkidu seeks solace from Shamhat who offers to bring him back with her to civilization. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Two''': Enkidu learns to eat human food, anoints his unkempt body, and dresses in civilized clothing. He longs to visit the Temple of Ishtar and to challenge the mighty King Gilgamesh. Upon learning that this supposedly exemplary ruler intends to sleep with a man's bride before their wedding, Enkidu becomes enraged. He goes with Shamhat to Uruk, where he blocks Gilgamesh's way to the bridal chamber. After a titanic battle that Gilgamesh wins, Gilgamesh shows no malice and he and Enkidu become the closest of friends. Gilgamesh proposes an adventure to the forbidden Cedar Forest, where they must kill the mighty Humbaba, the forest's demon guardian. Enkidu, knowing that the chief god, Enlil himself, has assigned Humbaba to this post, bitterly protests; but he ultimately agrees out of love for his new friend. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Three''': Gilgamesh and Enkidu prepare to journey to the Cedar Forest. They gain the blessing of Gilgamesh's mother, the goddess Ninsun, as well as the support of the sun-god [[Shamash]], who becomes their patron. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Four''': Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey westward to Lebanon and the Cedar Forest. Gilgamesh has a series of disturbing prophetic dreams, which Enkidu naively and inaccurately interprets as good omens. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Five''': Entering the forest, Gilgamesh and Enkidu are no match for the terrible Humbaba, but they are aided by their patron Shamash, who sends eight powerful winds (Whistling Wind, Piercing Wind, Blizzard, Evil Wind, Demon Wind, Ice Wind, Storm, Sandstorm) against the forest guardian. Now at Gilgamesh's mercy, Humbaba pleads for his life, promising to give the king all the lumber he desires. Enkidu, however, advises Gilgamesh to show no mercy. The two brutally slay Humbaba, disemboweling him. They then cut down the mighty cedar trees that he protected and raft back down the Euphrates to civilization. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Six''': Back in Uruk, the goddess Ishtar proposes marriage to Gilgamesh. Knowing the unfortunate fate of her previous lovers, he rejects her amorous advances. The spurned Ishtar demands that her father, Anu, send the "Bull of Heaven" to kill Gilgamesh for his impudence. Enkidu hunts down the bull and grasps it by the tail, while Gilgamesh, matador-like, delivers a killing thrust. Ishtar curses their feat, saying "Woe unto Gilgamesh who slandered me and killed the Bull of Heaven!" Enkidu, ever loyal to Gilgamesh, dares to insult the goddess. Ishtar and her priestesses go into deep mourning for the Bull Heaven, while Gilgamesh and the men of Uruk celebrate the masculine courage of the hero-king. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Seven''': The chief gods—Anu, Enlil, and Shamash—gather in council to determine the punishment for killing the Bull of Heaven and Humbaba. After debating the issue, they decide to spare Gilgamesh but condemn Enkidu. The loyal Enkidu becomes deathly ill and curses the sacred harlot Shamhat for bringing him out of his wild state. At Shamash's urging, however, he relents and blesses her, though in bitter and ironic terms. As he lies dying, he describes his abode in the Netherworld's "House of Dust" to the grieving Gilgamesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Eight''': Gilgamesh delivers a lengthy poetic eulogy to Enkidu. Deeply moved, the formerly invulnerable king laments the loss of his one true friend and realizes for the first time his own mortality. | ||

| + | :"What is this sleep which has seized you? You have turned dark and do not hear me!" | ||

| + | :But Enkidu's eyes do not move. Gilgamesh touched his heart, but it beat no longer. | ||

| + | :He covered his friend's face like a bride, swooping down over him like an eagle, | ||

| + | :and like a lioness deprived of her cubs, he keeps pacing to and fro. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Nine''': Seeking to avoid Enkidu's fate, Gilgamesh undertakes the perilous journey to visit the legendary [[Utnapishtim]] and his wife, the only humans to have survived the [[Deluge (mythology)|Great Flood]] and who were granted immortality by the gods. He travels to the world's highest peak, Mount Mashu, where he encounters the fearsome Scorpion-Beings that guard the gate blocking the final leg of his journey. He persuades them of the absoluteness of his purpose, and they allow him to enter. He travels onward on a seemingly endless path through bitter cold and darkness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Ten''': At a far distant seashore, Gilgamesh encounters the female tavern-keeper [[Siduri]], who attempts to dissuade him from his quest. He, however, is too deeply saddened by the loss of Enkidu—and too filled with anxiety over his own eventual death—to be deterred. Gilgamesh then crosses the Waters of Death with the ferryman Urshanabi, completing the journey and finally meeting with the immortal Utnapishtim. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Tablet Eleven''': Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh in detail about the great flood (see below) and reluctantly gives him a chance for immortality. He informs Gilgamesh that if he can stay awake for seven nights, he will become immortal. Attempting the task, Gilgamesh inevitably falls asleep. Utnapishtim informs him of a special plant that grows only at the bottom of the sea. While not exactly conferring immortality, it will make him young again. Tying stones to his feet to reach the deep, Gilgamesh retrieves the plant and hopes to bring it back to Uruk. He places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes, and it is stolen by a serpent. Gilgamesh returns to Uruk in despair, but the sight of its massive walls move him to praise. | ||

| − | ''' | + | *'''Tablet Twelve''': Although several of the tales in the first eleven tablets are thought to have originally been separate stories, on the tablets they have been well integrated into a coherent whole. The story on the twelfth tablet is clearly a later appendage, in which Enkidu is still alive and now has both a wife and a son. It begins with Gilgamesh sending Enkidu on a mission to the Underworld to retrieve objects sacred to Ishtar/Inanna, which Gilgamesh has lost. It ends with a discussion in which Enkidu answers several of Gilgamesh's questions regarding the fate of those in the next life. The story has marked similarities to the myth of Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree.<ref> The Huluppu Tree.</ref> |

| − | + | ==Gilgamesh and the Flood== | |

| − | [[ | + | The dove went and returned. No landing place came to view, it turned back."]] |

| + | The marked similarity between the story of [[Noah]]'s flood and the story told to Gilgamesh by Utnapishtim caused a major stir when the Epic of Gilgamesh was first rediscovered and publicized in the nineteenth century. Utnapishtim's story simultaneously confirmed some aspects of the Biblical account of the flood and yet radically challenged Biblical authority, especially if scholars were correct in their assessment that Gilgamesh pre-dated [[Genesis]]. | ||

| − | + | Details of the two accounts are so nearly identical in some respects that it is virtually impossible to deny that one borrows from the other. | |

| − | + | *Both involve a divine warning about the flood and an instruction to build a large, sealed boat for the survivor's family and animals. | |

| − | + | *Both speak of the survivor releasing a [[dove]] and a [[raven]] after the rains stop. | |

| − | + | *Both tell of the boat coming to rest on a mountain after all the rest of mankind has been drowned in the flood. | |

| − | + | *Both describe the survivor offering a sacrifice to God or the gods after descending from the ark. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *Both tell of the primary deity blessing the survivors after the sacrifice is complete. | |

| − | + | And yet, the differences between the two accounts are also striking. Besides the obvious difference of names, numbers, and places (Utnapishtim vs. Noah, seven days instead of 40, Mount Nimush instead of [[Mount Ararat]], a sparrow instead of a second flight of the dove, etc.), in the ''Gilgamesh'' story, Utnapishtim and his wife become immortal, while in Genesis, Noah is the last of mankind's long-lived ancestors—living more than 600 years—but not immortal. More importantly, the Genesis account allows for only one divine actor, while in ''Gilgamesh'' the functions of divinity are divided among several gods. Thus, in ''Gilgamesh,'' it is not the One God who determines to bring about the flood, but the gods collectively as a Heavenly Council. Utnapishtim receives his warning about the deluge not from [[Yahweh]], but from the water deity Ea/Enki, who is acting against the orders of the Council. In Genesis, the One God shows no remorse after causing the death of the rest of mankind, while in Gilgamesh, [[Ishtar]] weeps for her dead children and repents of having supported the idea of the flood in the Divine Assembly. | |

| − | + | The question remains: if one of the accounts borrowed from the other, which came first? Did Genesis retell the ''Gilgamesh'' account with a monotheistic twist, or did ''Gilgamesh'' pervert the true story of Noah's ark into a polytheistic form? Most scholars believe the latter explanation to be unlikely. For those who accept that Gilgamesh is earlier but also maintain that the Biblical story is accurate, one plausible explanation is that God revealed the truth through Genesis, while the Gilgamesh account is a primitive recollection filtered through the polytheistic culture of ancient [[Mesopotamia]]. | |

| + | ==Gilgamesh and the Fall of Adam== | ||

| + | The connection between the serpent who steals the plant of life in Tablet 11 and the serpent in the Garden of Eden story who robs [[Adam and Eve]] of access to the tree of life is well known. But there are additional parallels between the Gilgamesh Epic and the story of Adam's fall in Genesis 3. These are more subtle, but appear unmistakably, provided one takes the view that the forbidden "fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil" was a euphemism for carnal knowledge and that the fall was a sexual seduction. | ||

| + | *Enkidu in his wild state resembles Adam before the Fall, when he lived in harmony with the creatures of Eden. | ||

| + | *After Enkidu falls for the harlot's seduction, he is alienated from nature and the animals run off, resembling Adam and Eve's expulsion from Eden. | ||

| + | *Enkidu in his wild state was naked and hairy, but after the seduction he realizes he is naked, as Adam and Eve before the fall were naked and unashamed (Genesis 2:25), but afterwards were ashamed of their nakedness (Genesis 3:10). | ||

| + | *The harlot clothes Enkidu and leads him to the world of humans, as God clothed Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:21) and sent them forth from Eden to engage in the labors and hardships of farming life. | ||

| + | *When Enkidu was clothed, the harlot says to him, "You are wise, like a God... let us go to the world of men," in language reminiscent of the serpent's words to Adam, that the fruit had made him "like God" (Genesis 3:5), therefore he should be cast out of Eden. | ||

| + | *Enkidu's fate—made clear when on his deathbed (tablet 7) he cursed the prostitute for bringing the fate of death to him (through their sexual encounter)—resembles Adam's fate, which came upon him the day he ate of the fruit (had a sexual encounter with Eve), "for in the day that you eat of it you will die" (Genesis 2:17). | ||

| − | + | The story of Gilgamesh was well-known in the Israel of [[Solomon]]'s day, when the J-source (Yahwist) most likely wrote Genesis 2-3, according to bible critics. These parallels would have been apparent to Israelites, lending credence to the view that the original meaning of the Fall story was a thinly-disguised account of sexual malfeasance. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==History== | |

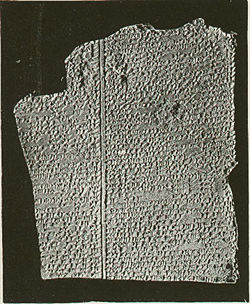

| + | [[image:GilgameshTablet.jpg|right|thumb|250px|The Deluge tablet of the Gilgamesh epic in Akkadian]] | ||

| − | + | ''Gilgamesh,'' the son of Lugalbanda, was, according to a [[Sumer|Sumerian]] king list, the fifth king of the city of Uruk, which was located about 155 miles south of modern [[Baghdad]]. In Mesopotamian mythology Gilgamesh is credited to have been a demi-god of superhuman strength, (a mythological equivalent to the Greek hero [[Hercules]]), who built the great wall of Uruk to defend his people from outer harm. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Gilgamesh's supposed historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2500 <small>B.C.E.</small>, 400 years prior to the earliest known written stories. The discovery of [[artifact]]s associated with two other kings named in the stories, Agga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic are thought to date from as early as the (2100 <small>B.C.E.</small> - 2000 <small>B.C.E.</small> The earliest Akkadian versions are dated to ca. 2000-1500 <small>B.C.E.</small> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Scholars believe that the flood myth on the eleventh tablet was largely borrowed from the Epic of Atrahasis. The twelfth tablet, which is sometimes appended to the remainder of the epic, represents a sequel to the original eleven, and was added at a later date. This tablet has commonly been omitted until recent years, as it is in a different style and is out of sequence with the rest of the tablets (''e.g.'' Enkidu is still alive).<ref>[http://www.mythome.org/gilgamesh12.html MythHome: Gilgamesh the 12th Tablet] Retrieved September 19, 2016.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | According to the Greek scholar Ioannis Kordatos, there are a large number of parallel verses as well as themes or episodes which indicate a substantial influence of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' on the ''[[Odyssey]],'' the Greek epic poem ascribed to [[Homer]].<ref>Ioannis Kakridis: "Eisagogi eis to Omiriko Zitima" (Introduction to the Homeric Question) In: ''Omiros: Odysseia,'' Edited with translation and comments by Zisimos Sideris. (Zacharopoulos Athens: Daidalos Press, I.)</ref> | |

| − | + | The first modern translation of the epic was in the 1870s by Assyriologist George Smith. More recent translations include one undertaken with the assistance of the American novelist John Gardner, and published in 1984. Another edition is the two volume critical work by Andrew George whose translation also appeared in the Penguin Classics series in 2003. In 2004, Stephen Mitchell released an edition. While it is highly readable, it is also controversial—being his interpretation of previous scholarly translations into what he calls the "New English version." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | + | *Cooper, Jerrold S. "Buddies in Babylonia - Gilgamesh, Enkidu and Mesopotamian Homosexuality," in Abusch, Tz (ed.), ''Riches Hidden in Secret Places - Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen.'' Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, (2002):73-85. | |

| − | + | *George, Andrew ''The Epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian.'' Penguin Classics, 2003 (original 1999). ISBN 0140449198 | |

| − | + | *George, Andrew. ''The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic - Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts'', 2 vols (2003). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198149224 | |

| + | * Foster, Benjamin R., (trans. & ed.). ''The Epic of Gilgamesh.'' New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0393975169 | ||

| + | *Hammond, D. & Jablow, A. "Gilgamesh and the Sundance Kid: the Myth of Male Friendship," in H. Brod, (ed.), ''The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies.'' Boston, (1987): 241-258. | ||

| + | * Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. ''The Epic of Gilgamesh.'' Stanford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0804717117 | ||

| + | * Jackson, Danny. ''The Epic of Gilgamesh.'' Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1997. ISBN 0865163529 | ||

| + | * Mitchell, Stephen. ''Gilgamesh: A New English Version.'' New York: Free Press, 2004. ISBN 074326164X | ||

| + | * Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius. ''The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh.'' Vol 1. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1997. ISBN 9514577604 | ||

| − | *http://www. | + | ==External links== |

| − | *[http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/mideast/mi-wtst.htm The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography] | + | All links retrieved June 21, 2017. |

| − | * | + | *Academy of Ancient Texts [http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/ Full text of Gilgamesh]. |

| − | + | *W. T. S. Thackara [http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/mideast/mi-wtst.htm The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography] ''theosophynw.org''. | |

| − | + | *Babylonian (Akkadian) texts: [http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=c.1.8.1* ETCSL] Electronic Texts Corpus Sumerian Literature | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.religioustolerance.org/noah_com.htm Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood] | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/noah_com.htm Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood] | ||

| − | * | + | *[http://www.christian-thinktank.com/gilgy09.html Comparison of the Flood in Genesis to the Epic of Gilgamesh and related literature] ''christian-thinktank.com''. |

| − | + | *[http://www.strippedbooks.com/comics/stripped03/gilgamesh01.html Stripped Books: Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh] - a comic-book adaptation of a talk by Stephen Mitchell about the epic poem. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] [[Category: Religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] [[Category: Religion]] | ||

{{Credit2|Epic_of_Gilgamesh|66821911|Gilgamesh|66718617}} | {{Credit2|Epic_of_Gilgamesh|66821911|Gilgamesh|66718617}} | ||

Latest revision as of 07:45, 24 January 2023

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from Babylonia and arguably the oldest known work of literature. The story includes a series of legends and poems integrated into a longer Akkadian epic about the hero-king Gilgamesh of Uruk (Erech, in the Bible), a ruler of the third millennium B.C.E. Several versions have survived, the most complete being preserved on eleven clay tablets in the library of the seventh-century B.C.E. Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

The essential story tells of the spiritual maturation of the heroic Gilgamesh, the powerful but self-centered king who tyrannizes his people and even disregards the gods. He is part divine and part human. Through his adventures, Gilgamesh first begins to know himself through experiencing the death of his only friend, Enkidu. Seeking the secret of eternal life, he travels on the archetypal hero's journey, ultimately returning to Uruk a much wiser man than when he left and reconciled to his mortality.

The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times and to have influenced important works of literature, from the book of Genesis to The Odyssey. One of the stories included in the epic directly parallels the story of Noah's flood.

Episodes in Gilgamesh foreshadow many other later stories in both Biblical and secular literature:

- The Fall of Man (the naked savage Enkidu's harmony with nature is broken when he is seduced by the prostitute Shamhat, who initiates him to "knowledge of good and evil," and makes him aware that he is naked and ashamed, at which point she clothes him)

- David and Jonathan (Enkidu's sacrificial loyalty for his rival, Gilgamesh)

- The Fruit of the Tree of Life (the plant of eternal youth stolen by a serpent)

- Hercules (Gilgamesh as the nearly immortal demi-god and great, but flawed, hero)

Even with its missing lines and far from seamless narrative style, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a work of great literature, made all the more wonderful because it predates all others. It is widely read in translation, and its hero has become a minor icon of popular culture.

Summary

The following is a summary of each of the tablets from the Epic of Gilgamesh:[1]

- Tablet 1: A narrator invites the reader to view the majesty of the city of Uruk and introduces us to its king, Gilgamesh. He is the greatest king on Earth, two-thirds god and one-third human, the strongest man who ever existed. Yet he reigns as a tyrant over his people in the city of Uruk, failing to sympathize with their plight and even exercising the supposed right to deflower brides before their husbands sleep with them.

When his people complain to the gods that he is too harsh, the gods decide to educate Gilgamesh. The mother goddess Aruru/Ninhursag creates the hairy wild-man Enkidu as a worthy rival. Enkidu lives wild among the gazelles of the forest. Enkidu destroys the traps of a trapper, who discovers him and requests that Gilgamesh send a temple-harlot to ensnare the wild man so the wild beasts will then reject him. Gilgamesh sends Shamhat, the sacred harlot of the goddess Ishtar, who seduces Enkidu into a week-long sexual initiation, in which Enkidu demonstrates unmatched virility. As a result of this encounter, the animals now fear him and flee his presence. Bereft, Enkidu seeks solace from Shamhat who offers to bring him back with her to civilization.

- Tablet Two: Enkidu learns to eat human food, anoints his unkempt body, and dresses in civilized clothing. He longs to visit the Temple of Ishtar and to challenge the mighty King Gilgamesh. Upon learning that this supposedly exemplary ruler intends to sleep with a man's bride before their wedding, Enkidu becomes enraged. He goes with Shamhat to Uruk, where he blocks Gilgamesh's way to the bridal chamber. After a titanic battle that Gilgamesh wins, Gilgamesh shows no malice and he and Enkidu become the closest of friends. Gilgamesh proposes an adventure to the forbidden Cedar Forest, where they must kill the mighty Humbaba, the forest's demon guardian. Enkidu, knowing that the chief god, Enlil himself, has assigned Humbaba to this post, bitterly protests; but he ultimately agrees out of love for his new friend.

- Tablet Three: Gilgamesh and Enkidu prepare to journey to the Cedar Forest. They gain the blessing of Gilgamesh's mother, the goddess Ninsun, as well as the support of the sun-god Shamash, who becomes their patron.

- Tablet Four: Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey westward to Lebanon and the Cedar Forest. Gilgamesh has a series of disturbing prophetic dreams, which Enkidu naively and inaccurately interprets as good omens.

- Tablet Five: Entering the forest, Gilgamesh and Enkidu are no match for the terrible Humbaba, but they are aided by their patron Shamash, who sends eight powerful winds (Whistling Wind, Piercing Wind, Blizzard, Evil Wind, Demon Wind, Ice Wind, Storm, Sandstorm) against the forest guardian. Now at Gilgamesh's mercy, Humbaba pleads for his life, promising to give the king all the lumber he desires. Enkidu, however, advises Gilgamesh to show no mercy. The two brutally slay Humbaba, disemboweling him. They then cut down the mighty cedar trees that he protected and raft back down the Euphrates to civilization.

- Tablet Six: Back in Uruk, the goddess Ishtar proposes marriage to Gilgamesh. Knowing the unfortunate fate of her previous lovers, he rejects her amorous advances. The spurned Ishtar demands that her father, Anu, send the "Bull of Heaven" to kill Gilgamesh for his impudence. Enkidu hunts down the bull and grasps it by the tail, while Gilgamesh, matador-like, delivers a killing thrust. Ishtar curses their feat, saying "Woe unto Gilgamesh who slandered me and killed the Bull of Heaven!" Enkidu, ever loyal to Gilgamesh, dares to insult the goddess. Ishtar and her priestesses go into deep mourning for the Bull Heaven, while Gilgamesh and the men of Uruk celebrate the masculine courage of the hero-king.

- Tablet Seven: The chief gods—Anu, Enlil, and Shamash—gather in council to determine the punishment for killing the Bull of Heaven and Humbaba. After debating the issue, they decide to spare Gilgamesh but condemn Enkidu. The loyal Enkidu becomes deathly ill and curses the sacred harlot Shamhat for bringing him out of his wild state. At Shamash's urging, however, he relents and blesses her, though in bitter and ironic terms. As he lies dying, he describes his abode in the Netherworld's "House of Dust" to the grieving Gilgamesh.

- Tablet Eight: Gilgamesh delivers a lengthy poetic eulogy to Enkidu. Deeply moved, the formerly invulnerable king laments the loss of his one true friend and realizes for the first time his own mortality.

- "What is this sleep which has seized you? You have turned dark and do not hear me!"

- But Enkidu's eyes do not move. Gilgamesh touched his heart, but it beat no longer.

- He covered his friend's face like a bride, swooping down over him like an eagle,

- and like a lioness deprived of her cubs, he keeps pacing to and fro.

- Tablet Nine: Seeking to avoid Enkidu's fate, Gilgamesh undertakes the perilous journey to visit the legendary Utnapishtim and his wife, the only humans to have survived the Great Flood and who were granted immortality by the gods. He travels to the world's highest peak, Mount Mashu, where he encounters the fearsome Scorpion-Beings that guard the gate blocking the final leg of his journey. He persuades them of the absoluteness of his purpose, and they allow him to enter. He travels onward on a seemingly endless path through bitter cold and darkness.

- Tablet Ten: At a far distant seashore, Gilgamesh encounters the female tavern-keeper Siduri, who attempts to dissuade him from his quest. He, however, is too deeply saddened by the loss of Enkidu—and too filled with anxiety over his own eventual death—to be deterred. Gilgamesh then crosses the Waters of Death with the ferryman Urshanabi, completing the journey and finally meeting with the immortal Utnapishtim.

- Tablet Eleven: Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh in detail about the great flood (see below) and reluctantly gives him a chance for immortality. He informs Gilgamesh that if he can stay awake for seven nights, he will become immortal. Attempting the task, Gilgamesh inevitably falls asleep. Utnapishtim informs him of a special plant that grows only at the bottom of the sea. While not exactly conferring immortality, it will make him young again. Tying stones to his feet to reach the deep, Gilgamesh retrieves the plant and hopes to bring it back to Uruk. He places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes, and it is stolen by a serpent. Gilgamesh returns to Uruk in despair, but the sight of its massive walls move him to praise.

- Tablet Twelve: Although several of the tales in the first eleven tablets are thought to have originally been separate stories, on the tablets they have been well integrated into a coherent whole. The story on the twelfth tablet is clearly a later appendage, in which Enkidu is still alive and now has both a wife and a son. It begins with Gilgamesh sending Enkidu on a mission to the Underworld to retrieve objects sacred to Ishtar/Inanna, which Gilgamesh has lost. It ends with a discussion in which Enkidu answers several of Gilgamesh's questions regarding the fate of those in the next life. The story has marked similarities to the myth of Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree.[2]

Gilgamesh and the Flood

The dove went and returned. No landing place came to view, it turned back."]] The marked similarity between the story of Noah's flood and the story told to Gilgamesh by Utnapishtim caused a major stir when the Epic of Gilgamesh was first rediscovered and publicized in the nineteenth century. Utnapishtim's story simultaneously confirmed some aspects of the Biblical account of the flood and yet radically challenged Biblical authority, especially if scholars were correct in their assessment that Gilgamesh pre-dated Genesis.

Details of the two accounts are so nearly identical in some respects that it is virtually impossible to deny that one borrows from the other.

- Both involve a divine warning about the flood and an instruction to build a large, sealed boat for the survivor's family and animals.

- Both speak of the survivor releasing a dove and a raven after the rains stop.

- Both tell of the boat coming to rest on a mountain after all the rest of mankind has been drowned in the flood.

- Both describe the survivor offering a sacrifice to God or the gods after descending from the ark.

- Both tell of the primary deity blessing the survivors after the sacrifice is complete.

And yet, the differences between the two accounts are also striking. Besides the obvious difference of names, numbers, and places (Utnapishtim vs. Noah, seven days instead of 40, Mount Nimush instead of Mount Ararat, a sparrow instead of a second flight of the dove, etc.), in the Gilgamesh story, Utnapishtim and his wife become immortal, while in Genesis, Noah is the last of mankind's long-lived ancestors—living more than 600 years—but not immortal. More importantly, the Genesis account allows for only one divine actor, while in Gilgamesh the functions of divinity are divided among several gods. Thus, in Gilgamesh, it is not the One God who determines to bring about the flood, but the gods collectively as a Heavenly Council. Utnapishtim receives his warning about the deluge not from Yahweh, but from the water deity Ea/Enki, who is acting against the orders of the Council. In Genesis, the One God shows no remorse after causing the death of the rest of mankind, while in Gilgamesh, Ishtar weeps for her dead children and repents of having supported the idea of the flood in the Divine Assembly.

The question remains: if one of the accounts borrowed from the other, which came first? Did Genesis retell the Gilgamesh account with a monotheistic twist, or did Gilgamesh pervert the true story of Noah's ark into a polytheistic form? Most scholars believe the latter explanation to be unlikely. For those who accept that Gilgamesh is earlier but also maintain that the Biblical story is accurate, one plausible explanation is that God revealed the truth through Genesis, while the Gilgamesh account is a primitive recollection filtered through the polytheistic culture of ancient Mesopotamia.

Gilgamesh and the Fall of Adam

The connection between the serpent who steals the plant of life in Tablet 11 and the serpent in the Garden of Eden story who robs Adam and Eve of access to the tree of life is well known. But there are additional parallels between the Gilgamesh Epic and the story of Adam's fall in Genesis 3. These are more subtle, but appear unmistakably, provided one takes the view that the forbidden "fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil" was a euphemism for carnal knowledge and that the fall was a sexual seduction.

- Enkidu in his wild state resembles Adam before the Fall, when he lived in harmony with the creatures of Eden.

- After Enkidu falls for the harlot's seduction, he is alienated from nature and the animals run off, resembling Adam and Eve's expulsion from Eden.

- Enkidu in his wild state was naked and hairy, but after the seduction he realizes he is naked, as Adam and Eve before the fall were naked and unashamed (Genesis 2:25), but afterwards were ashamed of their nakedness (Genesis 3:10).

- The harlot clothes Enkidu and leads him to the world of humans, as God clothed Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:21) and sent them forth from Eden to engage in the labors and hardships of farming life.

- When Enkidu was clothed, the harlot says to him, "You are wise, like a God... let us go to the world of men," in language reminiscent of the serpent's words to Adam, that the fruit had made him "like God" (Genesis 3:5), therefore he should be cast out of Eden.

- Enkidu's fate—made clear when on his deathbed (tablet 7) he cursed the prostitute for bringing the fate of death to him (through their sexual encounter)—resembles Adam's fate, which came upon him the day he ate of the fruit (had a sexual encounter with Eve), "for in the day that you eat of it you will die" (Genesis 2:17).

The story of Gilgamesh was well-known in the Israel of Solomon's day, when the J-source (Yahwist) most likely wrote Genesis 2-3, according to bible critics. These parallels would have been apparent to Israelites, lending credence to the view that the original meaning of the Fall story was a thinly-disguised account of sexual malfeasance.

History

Gilgamesh, the son of Lugalbanda, was, according to a Sumerian king list, the fifth king of the city of Uruk, which was located about 155 miles south of modern Baghdad. In Mesopotamian mythology Gilgamesh is credited to have been a demi-god of superhuman strength, (a mythological equivalent to the Greek hero Hercules), who built the great wall of Uruk to defend his people from outer harm.

Gilgamesh's supposed historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2500 B.C.E., 400 years prior to the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with two other kings named in the stories, Agga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.

The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic are thought to date from as early as the (2100 B.C.E. - 2000 B.C.E. The earliest Akkadian versions are dated to ca. 2000-1500 B.C.E.

Scholars believe that the flood myth on the eleventh tablet was largely borrowed from the Epic of Atrahasis. The twelfth tablet, which is sometimes appended to the remainder of the epic, represents a sequel to the original eleven, and was added at a later date. This tablet has commonly been omitted until recent years, as it is in a different style and is out of sequence with the rest of the tablets (e.g. Enkidu is still alive).[3]

According to the Greek scholar Ioannis Kordatos, there are a large number of parallel verses as well as themes or episodes which indicate a substantial influence of the Epic of Gilgamesh on the Odyssey, the Greek epic poem ascribed to Homer.[4]

The first modern translation of the epic was in the 1870s by Assyriologist George Smith. More recent translations include one undertaken with the assistance of the American novelist John Gardner, and published in 1984. Another edition is the two volume critical work by Andrew George whose translation also appeared in the Penguin Classics series in 2003. In 2004, Stephen Mitchell released an edition. While it is highly readable, it is also controversial—being his interpretation of previous scholarly translations into what he calls the "New English version."

Notes

- ↑ Tablet One: The Epic of Gilgamesh Translated by Maureen Gallery Kovacs. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ The Huluppu Tree.

- ↑ MythHome: Gilgamesh the 12th Tablet Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Ioannis Kakridis: "Eisagogi eis to Omiriko Zitima" (Introduction to the Homeric Question) In: Omiros: Odysseia, Edited with translation and comments by Zisimos Sideris. (Zacharopoulos Athens: Daidalos Press, I.)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cooper, Jerrold S. "Buddies in Babylonia - Gilgamesh, Enkidu and Mesopotamian Homosexuality," in Abusch, Tz (ed.), Riches Hidden in Secret Places - Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, (2002):73-85.

- George, Andrew The Epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. Penguin Classics, 2003 (original 1999). ISBN 0140449198

- George, Andrew. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic - Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, 2 vols (2003). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198149224

- Foster, Benjamin R., (trans. & ed.). The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0393975169

- Hammond, D. & Jablow, A. "Gilgamesh and the Sundance Kid: the Myth of Male Friendship," in H. Brod, (ed.), The Making of Masculinities: The New Men's Studies. Boston, (1987): 241-258.

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Stanford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0804717117

- Jackson, Danny. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1997. ISBN 0865163529

- Mitchell, Stephen. Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press, 2004. ISBN 074326164X

- Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius. The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh. Vol 1. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1997. ISBN 9514577604

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Academy of Ancient Texts Full text of Gilgamesh.

- W. T. S. Thackara The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography theosophynw.org.

- Babylonian (Akkadian) texts: ETCSL Electronic Texts Corpus Sumerian Literature

- Comparison of The Epic of Gilgamesh to the Genesis flood

- Comparison of the Flood in Genesis to the Epic of Gilgamesh and related literature christian-thinktank.com.

- Stripped Books: Stephen Mitchell on Gilgamesh - a comic-book adaptation of a talk by Stephen Mitchell about the epic poem.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.