Difference between revisions of "Death of God" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→External links) |

m (→Impact) |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

==Impact== | ==Impact== | ||

[[Image:God-is-not-dead.jpg|thumb|200px|A church's Cross declares "God is not dead."]] | [[Image:God-is-not-dead.jpg|thumb|200px|A church's Cross declares "God is not dead."]] | ||

| − | Nietzsche's prophecies regarding the significance of the "death of God" have yet to be realized. Since the 1960s, Christians have answered Nietzsche's challenge with | + | Nietzsche's prophecies regarding the significance of the "death of God" have yet to be realized. Since the 1960s, Christians have answered Nietzsche's challenge with slogans such as "'God is dead'... Nietzsche; 'Nietzsche is dead'... God." Indeed, religion appears to have undergone a rebirth in recent decades in many parts of the world. Nevertheless, the some of the philosophical attitudes of radical theology have indeed found their way into the main stream of western societies, both in a constructive and a destructive sense. |

| − | On the positive side, religious people tend less to surrender moral responsibility for world events to God, and | + | On the positive side, religious people tend less to surrender moral responsibility for world events to God, and that God's love is most meaningfully experienced in Christian community has become prevalent. On the other hand, Nietzsche indeed seems to have proven to be prophetic with regard to the prevalence of [[moral relativism]] and the growth of [[nihilism]] in contemporary society. The death of God movement in theology may have been doomed from the start by its very name, with which few religious people could ever associate themselves. However, its ideas remain extremely germane to the core issues human responsibility and God's relationship—if any—to the world of human existence. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 00:00, 26 August 2008

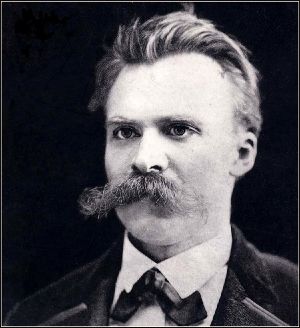

The theology of the Death of God, also known as Radical Theology, is a contemporary theological movement challenging traditional Judeo-Christian beliefs about the God and asserting that human beings must take moral and spiritual responsibility for themselves. The term "death of God" originated from the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche in the nineteenth century, and were later seized upon by several theological writers of the mid twentieth century.

For Nietzsche, the death of the Christian concept of God signaled a moral and spiritual crisis for modern civilization, but also meant that people could free themselves from externally-imposed limitation and develop themselves into a new type of heroic human being which he called the Übermensch (superman). Nietzsche's ideas were refined and carried forward in the philosophy of Martin Heidegger and the theology of Christian existentialists who emphasized human moral and spiritual responsibility.

In the 1960s, the death of God movement in Christian theology rejected the concept of a transcendent God, while affirming that God's immanent love could be experienced in the Christian community. Gabriel Vahanian and Thomas J. J. Altizer were leading exponents of this view. In the Jewish tradition, Richard Rubenstein's book After Auschwitz" made a major impact on Jewish culture, arguing that Jews must take history into their own hands and reject the idea that the suffering of the Jews is due to God's just punishment of their sins.

Although the concept of the death of God its failed to gain popular acceptance, many of its associated ideas have won considerably popularity.

Origins

"God is dead" (German: "Gott ist tot") is a widely-quoted and sometimes misconstrued statement by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. It first appears in The Gay Science, but is found several times in Nietzsche's writings, most famously in his classic work Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Also sprach Zarathustra).

In Nietzsche's though, "God is dead" is not meant literally, as in "God is now physically dead." Rather, it is his way of saying that the idea of God is no longer capable of acting as a source of any moral code or sense of directed historical purpose. Nietzsche recognized the crisis which the "death of God" represents for existing moral considerations. "When one gives up the Christian faith," he wrote, "one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one's feet. This morality is by no means self-evident... By breaking one main concept out of Christianity, the faith in God, one breaks the whole: nothing necessary remains in one's hands."[1]

The death of God is thus a way of saying that modern humans are no longer able to believe blindly in any the cosmic order described by the Christian religion. The death of God will lead, Nietzsche says, not only to the rejection of a belief of cosmic order but also to a rejection of absolute values themselves—to the rejection of belief in an objective and universal moral law, binding upon all individuals. In this manner, the loss of an absolute basis for morality leads to nihilism. This meant, to Nietzsche, that one must look for foundations that go beyond than the traditional Christian values.

Nietzsche believed that the majority of people did not recognize, or refused to acknowledge, this death of God out of their deepest-seated fear or angst. Therefore, when the death of God did begin to become widely acknowledged, people would despair and nihilism would become rampant, including the relativistic belief that human will is a law unto itself—anything goes and all is permitted. To Nietzsche, nihilism is the consequence of any idealistic philosophical system, because all idealisms suffer from the same weakness as Christian morality—that there is no "foundation" to build on. He therefore describes himself as "a 'subterranean man' at work, one who tunnels and mines and undermines."[2]

New possibilities

Nietzsche believed there could be positive possibilities for humans without God. Relinquishing the belief in God, he wrote, opens the way for human creative abilities to fully develop. With the concept of God holding them back, human beings might stop turning their eyes toward a supernatural realm and begin to acknowledge the value of this world.

Nietzsche uses the metaphor of an open sea, which can be both exhilarating and terrifying, to describe the potential of the death of God. Those people who eventually learn to create their lives anew will represent a new stage in human existence, the Übermensch, who, through the conquest of his or her own nihilism, becomes a mythical hero.

What is more, Zarathustra later refers, not only to the death of God, but that 'Dead are all the Gods'. It is not just one morality that has died, but all of them, to be replaced by the life of the übermensch, the new man:

'DEAD ARE ALL THE GODS: NOW DO WE DESIRE THE SUPERMAN TO LIVE.'

trans. Thomas Common, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part I, Section XXII,3

Nietzsche and Heidegger

Martin Heidegger came to grips with this part of Nietzsche's philosophy by looking at it as death of metaphysics. In his view, Nietzsche's words can only be understood as referring not to the concept of God per sem but to the end of philosophy itself. Philosophy had, in Heidegger's words, reached its maximum potential as metaphysics, and Nietzsche's words warn us of its demise and that of any metaphysical world view. If metaphysics is dead, Heidegger warned, it is because from its inception that was its fate.[3]

Radical theology and the Death of God

As Nietzsche's idea sprouted in the minds of twentieth century intellectuals, they gradually bore fruit in existentialist theology and other theological trends which downplay the impact on God's direct involvement with history.

By the 1960s, the he death of God theological movement had developed a considerable influence. Also known as "radical theology," it is sometimes technically referred to as "theothanatology," derived from the Greek Theos (God) and Thanatos (death).

The cover of Time magazine on April 8, 1966 boldly asked "Is God Dead?" The accompanying article concerned the movement in American theology that arose in the 1960s known as the "death of God."

The main protagonists of this theology included the Christian theologians Gabriel Vahanian, Paul van Buren, William Hamilton, and Thomas J. J. Altizer, and the Jewish rabbi Richard Rubenstein.

In 1961 Vahanian's book The Death of God was published. Vahanian argued that modern secular culture had lost all sense of the sacred, lacking any sacramental meaning, no transcendental purpose or sense of providence. He concluded that for the modern mind "God is dead." However, he did not mean that God did not exist. In Vahanian's vision, a transformed post-Christian and post-modern culture was needed to create a renewed experience of deity. Van Buren and Hamilton agreed that the concept of divine transcendence had lost any meaningful place in modern thought. According to the norms of contemporary modern thought, God is dead. In responding to this collapse in the concept of transcendence, Van Buren and Hamilton offered secular people the option of Jesus as the model human who acted in love. Thus, even though the transcendent God was no longer relative, the immanent God could be experienced through the love of Jesus, as experienced in the Christian church.

Altizer's "radical theology" of the death of God drew upon William Blake, as well as Hegelian thought and Nietzschean ideas. He conceived of theology as a form of poetry, in which—as with Van Buren and Hamilton— the immanence (presence) of God could be encountered in faith communities. However, he no longer accepted the possibility of affirming belief in a transcendent God even theoretically. Altizer concluded that God had incarnated in Christ and imparted his immanent spirit through him. This remained in the world through the church even though Jesus, the incarnate God, was dead. Altizer thus believed that the transcendent God had truly died, not just in theory, but also in reality.

The death of God in Judaism

Writing after the Holocaust, Richard Rubenstein expressed the theology of the death of God in contemporary Jewish context. He argued that the the concept of the Jewish God of history could no longer survive as a result of the experience of the Jews during WWII. Traditional Judaism had longed believed that Jewish suffering was justly imposed on them by God, but for Rubenstein, the experience of the Holocaust made this view both untenable and morally heinous. He argued that is no longer possible to believe in the God of the Abrahamic covenant who rewards and punishes his chosen people. Instead, Jews must act to take history into their own hands and not meekly rely on God's intervention to protect them from persecution. In a technical sense Rubenstein maintained, based on the Kabbalah, that God had "died" in creating the world through the process of Tzimtzum, by retracting Himself into a void to make space for existence.

Rubenstein's views struck a resonant chord with secular Jews in the early days of newly-formed state of Israel, which struggled to create a secure homeland for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Thus, unlike other "death of God" theologians, his ideas regarding human responsibility in history made a large impact on the mainstream Jewish community, even though the concept of the death of God itself was rejected by religious Jews. After Auschwitz thus not only earned him the title of the Jewish Death of God theologian, but also launched a the field of theological inquiry known as Holocaust theology.

Impact

Nietzsche's prophecies regarding the significance of the "death of God" have yet to be realized. Since the 1960s, Christians have answered Nietzsche's challenge with slogans such as "'God is dead'... Nietzsche; 'Nietzsche is dead'... God." Indeed, religion appears to have undergone a rebirth in recent decades in many parts of the world. Nevertheless, the some of the philosophical attitudes of radical theology have indeed found their way into the main stream of western societies, both in a constructive and a destructive sense.

On the positive side, religious people tend less to surrender moral responsibility for world events to God, and that God's love is most meaningfully experienced in Christian community has become prevalent. On the other hand, Nietzsche indeed seems to have proven to be prophetic with regard to the prevalence of moral relativism and the growth of nihilism in contemporary society. The death of God movement in theology may have been doomed from the start by its very name, with which few religious people could ever associate themselves. However, its ideas remain extremely germane to the core issues human responsibility and God's relationship—if any—to the world of human existence.

See also

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Martin Heidegger

- Christian Theology

- Holocaust

- Existentialism

Notes

- ↑ trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale; Twilight of the Idols, Expeditions of an Untimely Man, sect. 5

- ↑ trans. Hollingdale; Daybreak, Preface, sect. 1. New York : Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 9780521286626

- ↑ Wolfgan Muller-Lauter, Heidegger und Nietzsche: Nietzsche-Interpretationen III, Walter de Gruyter 2000. ISBN 9783495457023

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Altizer, Thomas J. J., and William Hamilton. Radical Theology and the Death of God. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966. OCLC 383781

- Haynes, Stephen R., and John K. Roth. The Death of God Movement and the Holocaust: Radical Theology Encounters the Shoah. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1999. ISBN 9780313303654

- Kaufmann, Walter. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974. ISBN 9780691019833

- Roberts, Tyler T. Contesting Spirit: Nietzsche, Affirmation, Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780691001272

- Rubenstein, Richard L. After Auschwitz; Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966. OCLC 2118249

- Vahanian, Gabriel. The Death of God; The Culture of Our Post-Christian Era. New York: G. Braziller, 1961. OCLC 312626

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.