Difference between revisions of "Death of God" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Origins) |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[[Martin Heidegger]] came to grips with this part of Nietzsche's philosophy by looking at it as death of [[metaphysics]]. In his view, Nietzsche's words can only be understood as referring not to the concept of God ''per se''m but to the end of philosophy itself. Philosophy had, in Heidegger's words, reached its maximum potential as metaphysics, and Nietzsche's words warn us of its demise and that of any metaphysical world view. If metaphysics is dead, Heidegger warned, it is because from its inception that was its fate.<ref>Wolfgan Muller-Lauter, ''Heidegger und Nietzsche: Nietzsche-Interpretationen III'', Walter de Gruyter 2000. ISBN 9783495457023</ref> | [[Martin Heidegger]] came to grips with this part of Nietzsche's philosophy by looking at it as death of [[metaphysics]]. In his view, Nietzsche's words can only be understood as referring not to the concept of God ''per se''m but to the end of philosophy itself. Philosophy had, in Heidegger's words, reached its maximum potential as metaphysics, and Nietzsche's words warn us of its demise and that of any metaphysical world view. If metaphysics is dead, Heidegger warned, it is because from its inception that was its fate.<ref>Wolfgan Muller-Lauter, ''Heidegger und Nietzsche: Nietzsche-Interpretationen III'', Walter de Gruyter 2000. ISBN 9783495457023</ref> | ||

| − | == Death of God | + | == Radical theology and the Death of God == |

| − | + | As Nietzsche's idea sprouted in the minds of twentieth century intellectuals, they gradually bore fruit in [[existentialism|existentialist]] theology and other theological trends which downplay the impact on God's direct involvement with history. | |

| + | |||

| + | By the 1960s, the he death of God theological movement had developed a considerable influence. Also known as "radical theology," it is sometimes technically referred to as "theothanatology," derived from the Greek ''[[Theos]]'' (God) and ''[[Thanatos]]'' (death). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The cover of ''Time'' magazine on April 8, 1966 boldly asked "Is God Dead?" The accompanying article concerned the movement in American [[theology]] that arose in the 1960s known as the "death of God." | ||

The main protagonists of this [[theology]] included the Christian theologians [[Gabriel Vahanian]], Paul van Buren, William Hamilton, and [[Thomas J. J. Altizer]], and the Jewish [[rabbi]] [[Richard Rubenstein]]. | The main protagonists of this [[theology]] included the Christian theologians [[Gabriel Vahanian]], Paul van Buren, William Hamilton, and [[Thomas J. J. Altizer]], and the Jewish [[rabbi]] [[Richard Rubenstein]]. | ||

| − | In 1961 Vahanian's book ''The Death of God'' was published. Vahanian argued that modern secular culture had lost all sense of the sacred, lacking any sacramental meaning, no transcendental purpose or sense of providence. He concluded that for the modern mind "God is dead, | + | In 1961 Vahanian's book ''The Death of God'' was published. Vahanian argued that modern secular culture had lost all sense of the sacred, lacking any sacramental meaning, no transcendental purpose or sense of providence. He concluded that for the modern mind "God is dead." However, he did not mean that God did not exist. In Vahanian's vision, a transformed [[post-Christian]] and post-modern culture was needed to create a renewed experience of [[deity]]. Van Buren and Hamilton agreed that the concept of divine [[transcendence]] had lost any meaningful place in modern thought. According to the norms of contemporary modern thought, God ''is'' dead. In responding to this collapse in the concept of transcendence, Van Buren and Hamilton offered secular people the option of [[Jesus]] as the model human who acted in love. Thus, even though the transcendent God was no longer relative, the immanent God could be experienced through the love of Jesus, as experienced in the Christian church. |

| + | |||

| + | Altizer's "radical theology" of the death of God drew upon [[William Blake]], as well as [[Hegel]]ian thought and Nietzschean ideas. He conceived of theology as a form of [[poetry]], in which—as with Van Buren and Hamilton— the [[immanence]] (presence) of God could be encountered in faith communities. However, he no longer accepted the possibility of affirming belief in a [[transcendent]] God even theoretically. Altizer concluded that God had incarnated in [[Christ]] and imparted his [[immanent]] [[spirit]] through him. This remained in the world through the church even though [[Jesus]], the incarnate God, was dead. Altizer thus believed that the transcendent God had truly died, not just in theory, but also in reality. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The death of God in Judaism=== | ||

| − | + | Writing after the Holocaust, [[Richard Rubenstein]] expressed the theology of the death of God in contemporary Jewish context. He argued that the the concept of the Jewish God of history could no longer survive as a result of the experience of the Jews during WWII. Traditional Judaism had longed believed that Jewish suffering was justly imposed on them by God, but for Rubenstein, the experience of the Holocaust made this view both untenable and morally heinous. He argued that is no longer possible to believe in the God of the Abrahamic covenant who rewards and punishes his chosen people. Instead, Jews must act to take history into their own hands and not meekly rely on God's intervention to protect them from persecution. In a technical sense Rubenstein maintained, based on the [[Kabbalah]], that God had "died" in creating the world through the process of Tzimtzum, by retracting Himself into a void to make space for existence. | |

| − | Rubenstein | + | Rubenstein's views struck a resonant chord with secular Jews in the early days of newly-formed state of Israel, which struggled to create a secure homeland for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Thus, unlike other "death of God" theologians, his ideas regarding human responsibility in history made a large impact on the mainstream Jewish community, even though the concept of the death of God itself was rejected by religious Jews. ''After Auschwitz'' thus not only earned him the title of the Jewish Death of God theologian, but also launched a the field of theological inquiry known as [[Holocaust theology]]. |

== Notable references in popular culture == | == Notable references in popular culture == | ||

Revision as of 21:44, 25 August 2008

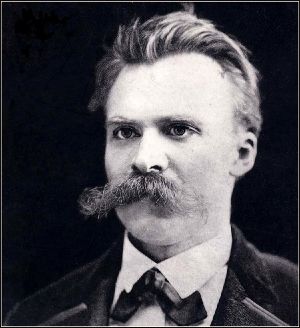

The theology of the Death of God, also known as Radical Theology is a contemporary theological movement challenging traditional Judeo-Christian beliefs regarding a transcendent God of history who intervenes in human affairs and asserting that human beings must take moral and responsibility for themselves. The term "death of God" originated from the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche in the nineteenth century, and was later seized upon by several theological writers of the mid twentieth century.

Origins

"God is dead" (German: "Gott ist tot") is a widely-quoted and sometimes misconstrued statement by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. It first appears in The Gay Science, but is found several times in Nietzsche's writings, most famously in his classic work Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Also sprach Zarathustra).

In Nietzsche's though, "God is dead" is not meant literally, as in "God is now physically dead." Rather, it is his way of saying that the idea of God is no longer capable of acting as a source of any moral code or sense of directed historical purpose. Nietzsche recognized the crisis which the "death of God" represents for existing moral considerations. "When one gives up the Christian faith," he wrote, "one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one's feet. This morality is by no means self-evident... By breaking one main concept out of Christianity, the faith in God, one breaks the whole: nothing necessary remains in one's hands."[1]

The death of God is thus a way of saying that modern humans are no longer able to believe blindly in any the cosmic order described by the Christian religion. The death of God will lead, Nietzsche says, not only to the rejection of a belief of cosmic order but also to a rejection of absolute values themselves—to the rejection of belief in an objective and universal moral law, binding upon all individuals. In this manner, the loss of an absolute basis for morality leads to nihilism. This meant, to Nietzsche, that one must look for foundations that go beyond than the traditional Christian values.

Nietzsche believed that the majority of people did not recognize, or refused to acknowledge, this death of God out of their deepest-seated fear or angst. Therefore, when the death of God did begin to become widely acknowledged, people would despair and nihilism would become rampant, including the relativistic belief that human will is a law unto itself—anything goes and all is permitted. To Nietzsche, nihilism is the consequence of any idealistic philosophical system, because all idealisms suffer from the same weakness as Christian morality—that there is no "foundation" to build on. He therefore describes himself as "a 'subterranean man' at work, one who tunnels and mines and undermines."[2]

New possibilities

Nietzsche believed there could be positive possibilities for humans without God. Relinquishing the belief in God, he wrote, opens the way for human creative abilities to fully develop. With the concept of God holding them back, human beings might stop turning their eyes toward a supernatural realm and begin to acknowledge the value of this world.

Nietzsche uses the metaphor of an open sea, which can be both exhilarating and terrifying, to describe the potential of the death of God. Those people who eventually learn to create their lives anew will represent a new stage in human existence, the Übermensch, who, through the conquest of his or her own nihilism, becomes a mythical hero.

What is more, Zarathustra later refers, not only to the death of God, but that 'Dead are all the Gods'. It is not just one morality that has died, but all of them, to be replaced by the life of the übermensch, the new man:

'DEAD ARE ALL THE GODS: NOW DO WE DESIRE THE SUPERMAN TO LIVE.'

trans. Thomas Common, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part I, Section XXII,3

Nietzsche and Heidegger

Martin Heidegger came to grips with this part of Nietzsche's philosophy by looking at it as death of metaphysics. In his view, Nietzsche's words can only be understood as referring not to the concept of God per sem but to the end of philosophy itself. Philosophy had, in Heidegger's words, reached its maximum potential as metaphysics, and Nietzsche's words warn us of its demise and that of any metaphysical world view. If metaphysics is dead, Heidegger warned, it is because from its inception that was its fate.[3]

Radical theology and the Death of God

As Nietzsche's idea sprouted in the minds of twentieth century intellectuals, they gradually bore fruit in existentialist theology and other theological trends which downplay the impact on God's direct involvement with history.

By the 1960s, the he death of God theological movement had developed a considerable influence. Also known as "radical theology," it is sometimes technically referred to as "theothanatology," derived from the Greek Theos (God) and Thanatos (death).

The cover of Time magazine on April 8, 1966 boldly asked "Is God Dead?" The accompanying article concerned the movement in American theology that arose in the 1960s known as the "death of God."

The main protagonists of this theology included the Christian theologians Gabriel Vahanian, Paul van Buren, William Hamilton, and Thomas J. J. Altizer, and the Jewish rabbi Richard Rubenstein.

In 1961 Vahanian's book The Death of God was published. Vahanian argued that modern secular culture had lost all sense of the sacred, lacking any sacramental meaning, no transcendental purpose or sense of providence. He concluded that for the modern mind "God is dead." However, he did not mean that God did not exist. In Vahanian's vision, a transformed post-Christian and post-modern culture was needed to create a renewed experience of deity. Van Buren and Hamilton agreed that the concept of divine transcendence had lost any meaningful place in modern thought. According to the norms of contemporary modern thought, God is dead. In responding to this collapse in the concept of transcendence, Van Buren and Hamilton offered secular people the option of Jesus as the model human who acted in love. Thus, even though the transcendent God was no longer relative, the immanent God could be experienced through the love of Jesus, as experienced in the Christian church.

Altizer's "radical theology" of the death of God drew upon William Blake, as well as Hegelian thought and Nietzschean ideas. He conceived of theology as a form of poetry, in which—as with Van Buren and Hamilton— the immanence (presence) of God could be encountered in faith communities. However, he no longer accepted the possibility of affirming belief in a transcendent God even theoretically. Altizer concluded that God had incarnated in Christ and imparted his immanent spirit through him. This remained in the world through the church even though Jesus, the incarnate God, was dead. Altizer thus believed that the transcendent God had truly died, not just in theory, but also in reality.

The death of God in Judaism

Writing after the Holocaust, Richard Rubenstein expressed the theology of the death of God in contemporary Jewish context. He argued that the the concept of the Jewish God of history could no longer survive as a result of the experience of the Jews during WWII. Traditional Judaism had longed believed that Jewish suffering was justly imposed on them by God, but for Rubenstein, the experience of the Holocaust made this view both untenable and morally heinous. He argued that is no longer possible to believe in the God of the Abrahamic covenant who rewards and punishes his chosen people. Instead, Jews must act to take history into their own hands and not meekly rely on God's intervention to protect them from persecution. In a technical sense Rubenstein maintained, based on the Kabbalah, that God had "died" in creating the world through the process of Tzimtzum, by retracting Himself into a void to make space for existence.

Rubenstein's views struck a resonant chord with secular Jews in the early days of newly-formed state of Israel, which struggled to create a secure homeland for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Thus, unlike other "death of God" theologians, his ideas regarding human responsibility in history made a large impact on the mainstream Jewish community, even though the concept of the death of God itself was rejected by religious Jews. After Auschwitz thus not only earned him the title of the Jewish Death of God theologian, but also launched a the field of theological inquiry known as Holocaust theology.

Notable references in popular culture

- The bridge of Elton John's 1972 song "Levon" with lyrics by Bernie Taupin contains the line "The New York Times said God is dead."

- John Proctor recites "God Is Dead" towards the end of the play "The Crucible" by Arthur Miller.

- An episode of The Kids in the Hall features a sketch imitating a 1950s educational film centering around the phrase, first stated by Nietzschean philosophers and denied by skeptics, until it is finally proved that the unusually diminutive God is indeed dead.

- There are t-shirts with the following text:" "God is dead" - Nietzsche (beneath the first sentence) "Nietzsche is dead" - God." Some variations carry the third line," "Nietzsche is God" - Foucault.," as a reference to modern philosopher Michel Foucault.

- In the episode of the television series Andromeda: Una Salus Victus. The character Tyr Anasazi, a Nietzschean, after killing a large number of people says to Dylan Hunt jokingly: "We could let God sort them out, but someone told me he was dead." Hunt explains the reference to the philosopher's belief by remarking "that Nietzsche! What a comedian!"

See also

- Postmodern Christianity

- Deconstruction-and-religion

Notes

- ↑ trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale; Twilight of the Idols, Expeditions of an Untimely Man, sect. 5

- ↑ trans. Hollingdale; Daybreak, Preface, sect. 1. New York : Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 9780521286626

- ↑ Wolfgan Muller-Lauter, Heidegger und Nietzsche: Nietzsche-Interpretationen III, Walter de Gruyter 2000. ISBN 9783495457023

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heidegger, Martin. Nietzsches Wort 'Gott ist tot (1943) translated as The Word of Nietzsche: 'God Is Dead', in Holzwege, edited and translated by Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Kaufmann, Walter. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974. ISBN 0691072078 ISBN 9780691072074 ISBN 0691019835 ISBN 9780691019833

- Roberts, Tyler T. Contesting Spirit: Nietzsche, Affirmation, Religion Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 0691059373 ISBN 9780691059372 ISBN 0691001278 ISBN 9780691001272

Death of God theology

- Thomas J. J. Altizer, The Gospel of Christian Atheism (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966).

- Thomas J. J. Altizer and William Hamilton, Radical Theology and the Death of God (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966).

- Bernard Murchland, ed., The Meaning of the Death of God (New York: Random House, 1967).

- Gabriel Vahanian, The Death of God (New York: George Braziller, 1961).

External links

- "Death of God Theology" by John M. Frame. Retrieved October 7, 2007.

| |||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.