Difference between revisions of "Dante Alighieri" - New World Encyclopedia

(Dante article) |

(Dante article) |

||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

''The Divine Comedy'' is notable not just for its content, although that in itself is revolutionary. Dante is the first major poet to write an epic in the [[Christian]] tradition, and in so doing he demonstrated the durability of Biblical figures (such as Heaven and Hell, Satan and God) for telling stories of great drama and intrigue. Moreover, he is one of the first poets, major or otherwise, to tell a story not of heroes and battles but of personal crisis and introspection. Dante's ideal guide through Purgatory and Heaven is his true love, Beatrice; and in many ways it was through Dante that the ideal of a true, romantic love would come to permeate Western culture. | ''The Divine Comedy'' is notable not just for its content, although that in itself is revolutionary. Dante is the first major poet to write an epic in the [[Christian]] tradition, and in so doing he demonstrated the durability of Biblical figures (such as Heaven and Hell, Satan and God) for telling stories of great drama and intrigue. Moreover, he is one of the first poets, major or otherwise, to tell a story not of heroes and battles but of personal crisis and introspection. Dante's ideal guide through Purgatory and Heaven is his true love, Beatrice; and in many ways it was through Dante that the ideal of a true, romantic love would come to permeate Western culture. | ||

| − | ''The Divine Comedy'' is also notable | + | ''The Divine Comedy'' is also notable for its poetic techniques. For the poem, Dante invented a very simple but extremely powerful rhyme scheme called ''terza rima'', where the poem is broken up into three-line tersets which rhyme as follows: |

:a | :a | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

:c | :c | ||

| − | + | The rhyme scheme of the ''Divine Comedy'' (which is, sadly, difficult to reproduce in English without sounding forced) gives the reader a sense of onward movement — each terset introduces a new rhyme — while at the same time continuing with rhymes seen from the previous terset, creating a sense of gradual progress much like Dante's description of his gradual ascent through the worlds of the afterlife. ''Terza rima'' has become so closely associated with Dante that the mere use of it is often enough to indicate that a poet is alluding to Dante's works. | |

===Other Works=== | ===Other Works=== | ||

Revision as of 05:52, 21 May 2006

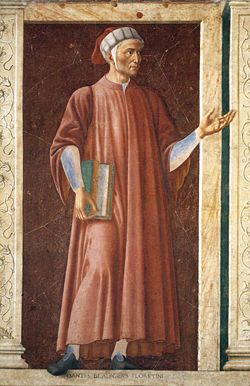

Durante degli Alighieri, better known as Dante, (c. June 1 1265 – September 14, 1321) was an Italian, Florentine poet. His greatest work, the epic poem The Divine Comedy, is considered the greatest literary statement produced in medieval Europe. Much like Chaucer in England and Alexander Pushkin in Russia, Dante is credited not only with creating a magnificent poetry; he is also considered to be the father of the modern Italian language itself. While the very language of The Divine Comedy would become so widespread that it would form the ground from which the Italian language would emerge, it is somewhat of an exaggeration. Although Dante is far and away the most popular and timeless poet of his century, he was by no means alone in ushering in Italian poetry; he was a contemporary (and in some cases, a friend) of such luminaries as Cavalcanti and Petrarch. Dante's contribution to the emergence of Renaissance literature was not limited to his poetry alone, but to the literary movement of his times in general.

Dante is sometimes considered to be the most important poet of the Renaissance. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that the Renaissance begins with Dante; that the first steps out of the ancient world and into the modern world were made by him. Often ranked alongside Homer and Virgil as one of the great epic poets for all times, Dante is certainly the most modern. While the epic poets of ancient times tended to celebrate the greatness and heroism of their respective nations (for Homer, Greece; for Virgil, Rome) Dante's objective in his epic is decidedly different: to explore Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven and, in so doing, reconcile Europe's Hellenic past with its Christian present.

Dante's epic has no epic battles, nor any towering heroes; its protagonist is Dante himself, a plain and (by his own admission) somewhat reserved Florentine. Its action consists, primarily, of Dante's encounters and conversations with the dead. In so doing, Dante establishes a dialogue with the past in a way never before realized, and leads the way into a future that would become the Renaissance — literally, the rebirth — of European culture, a recapturing and "baptizing" of its Hellenic past.

From Birth to Death

Early history and family

Dante was born in 1265 under the sign of Gemini (by his own account), placing his birthday between May 18th and June 17th. As an infant, Dante may have been originally christened 'Durante' in Florence's Baptistery, in which case Dante could be a shortened version of that name.

He was born into the prominent Alighieri family of Florence, whose loyalties were to the Guelfs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy, in opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor.

After the defeat of the Ghibellines by the Guelfs in 1289, the Guelfs themselves were divided into White Guelfs, who were wary of Papal influence, and Black Guelfs who continued to support the Papacy. Dante (a White Guelf) pretended that his family descended from the ancient Romans (Inferno, XV, 76), but the earliest relative he can mention by name is Cacciaguida degli Elisei (Paradiso, XV, 135), from no earlier than about 1100.

His father, Alighiero de Bellincione, was a White Guelf, but suffered no reprisals after the Ghibellines won the Battle of Montaperti, and this safety reveals a certain personal or family prestige.

Dante's mother was Donna Bella degli Abati; "Bella" stands for Gabriella, but also means "beautiful", while Abati (the name of a powerful family) means "abbot". She died when Dante was 5 or 6 years old, and Alighiero soon married Miss Lapa di Chiarissimo Cialuffi. (It is uncertain whether he really married her, as widowers had social limitations in these matters.) This woman definitely bore two children, Dante's brother Francesco and sister Tana (Gaetana).

When Dante was 12, in 1277, he was promised in marriage to Gemma di Manetto Donati, daughter of Messer Manetto Donati. Contracting marriages at this early age was quite common, and was an important ceremony, requiring formal deeds signed before a notary. Dante had several sons with Gemma. As often happens with famous people, many children pretended to be Dante's offspring; however, it is likely that four of them, Jacopo, Pietro, Gabrielle, and Antonia Alighieri were truly his children.

Education and poetry

Not much is known about Dante's education, though it is presumed he studied at home. We know he studied Tuscan poetry, at a time when the Sicilian School (Scuola poetica siciliana), a cultural group from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. His interests brought him to discover Provençal minstrels and poets, and Latin culture (with an obvious particular devotion to Virgil).

It should be underlined that during the "Secoli Bui" (Dark Ages), Italy had become a mosaic of small states, so Sicily was culturally and politically as far from Tuscany as was Provence: the regions did not share a language, culture, or easy communications. Nevertheless, we can assume that Dante was a keen up-to-date intellectual with international interests.

At age 18, he met Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Cino da Pistoia, and soon after Brunetto Latini; together they became the leaders of Dolce Stil Nuovo (The Sweet New Style), which became one of the leading literary movements of medieval Italy. Brunetto later received a special mention in the Divine Comedy (Inferno, XV, 82), for his contributions to Dante's development.

When he was nine years old he met Beatrice Portinari, the daughter of Folco Portinari, with whom he fell in love "at first sight", and apparently without even having spoken to her. He saw her frequently after age 18, often exchanging greetings in the street, but he never knew her well. It is hard to decipher of what this love consisted, but something extremely important for Italian culture was taking place: Dante, along with the rest of the Stil Nuevo poets, would lead the writers of the Renaissance to discover the themes of romantic Love (Amore), which had never been so emphasized before. His love for Beatrice would become Dante's reason for poetry and for living (as in a somewhat different fashion Petrarch would show for his Laura).

When Beatrice died in 1290, Dante tried to find a refuge in Latin literature. From the Convivio we know that he had read Boethius's De consolatione philosophiae and Cicero's De amicitia. He then dedicated himself to philosophical studies at religious schools like the Dominican one in Santa Maria Novella. He took part in the disputes between the two principal mendicant orders, the (Franciscans and Dominican)s. The Franciscans adhered to a mysterical doctrine of the mystics and of San Bonaventura, the latter Saint Thomas Aquinas. Dante would use Beatrice to criticize his "excessive" passion for philosophy in the second book of The Divine Comedy, Purgatorio.

Political Contexts

Dante, like many Florentines of his day, became embroiled in the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. He fought in the battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289), with Florentine Guelf knights against Arezzo Ghibellines. In 1294 he was among those knights who escorted Carlo Martello d'Anjou (son of Charles of Anjou) while he was in Florence.

To further his political career, he became a doctor and a pharmacist; he did not intend to take up those professions, but a law issued in 1295 required that nobles who wanted to assume public office had to be enrolled in one of the merchant guilds, so Dante obtained quick admission to the apothecaries' guild. The profession he chose was not entirely inapt, since at the time books were sold from apothecaries' shops. As a politician, he accomplished little of relevance, but he held various offices over a number of years in a city undergoing some political agitation.

Pope Boniface VIII was planning a military occupation of Florence. In 1301, the Pope appointed Charles de Valois, brother of King Philip IV of France, as peacemaker for Tuscany. Florence's city government was expecting a visit from him, but as they had treated the Pope's ambassadors badly a few weeks earlier, they feared he might have "unofficial" orders, so the council sent a delegation to Rome, in order to ascertain the Pope's intentions. Dante was made the chief of this delegation.

Exile and death

Boniface quickly sent away the other representatives and asked Dante alone to remain in Rome. At the same time (November 1, 1301) Charles de Valois was entering Florence with Black Guelfs, who for the next six days destroyed everything and killed most of their enemies. A new government was installed composed of Black Guelfs, with Messer Cante dei Gabrielli di Gubbio appointed mayor of Florence. The poet was still in Rome, where the Pope had "suggested" he remain, and was therefore considered a deserter. As a result, Dante was exiled from his native city and ordered to pay a substantive sum to atone for his absense from the battle. Since he could not pay his fine, he was condemned to perpetual exile. Had he been caught by Florentine soldiers, he would have been summarily executed.

The poet took part in several attempts by the White Guelfs to regain power, but these all failed due to treachery. Dante, bitter at the treatment he had received at the hands of his enemies, also grew disgusted with the infighting and ineffectiveness of his erstwhile allies, and vowed to become a party of one. At this point he began sketching the foundations for the Divine Comedy as a work in 100 cantos divided into three books of thirty-three cantos each, with a single introductory canto.

Dante went to Verona as a guest of Bartolomeo Della Scala, then moved to Sarzana, and afterwards he is supposed to have lived for some time in Lucca with Madame Gentucca, who made his stay comfortable (and was later gratefully mentioned in Purgatorio XXIV,37). Some speculative sources say that he was in Paris, too, between 1308 and 1310. Other sources, even less trustworthy, take him to Oxford.

In 1310 the German King Henry VII of Luxembourg invaded Italy; Dante saw in him the chance for revenge, so he wrote to him (and to other Italian princes) several public letters violently inciting them to destroy the Black Guelfs. Mixing religion and private concerns, he invoked the worst anger of God against his town, suggesting several particular targets that coincided with his personal enemies.

In 1312, Henry VII assaulted Florence and defeated the Black Guelfs, but there is no evidence that Dante was involved. Some say he refused to participate in the assault on his city by a foreigner; others suggest that his name had become unpleasant for White Guelfs also and that any trace of his passage had carefully been removed. In 1313 Henry VII died, and with him any residual hope for Dante to see Florence again. He returned to Verona, where a patron allowed him to live in security and, presumably, a fair degree of prosperity. Coincidentally, this patron would be, in Dante's poem, admitted to Paradise (Paradiso XVII, 76).

In 1315, Florence was forced by a military officer to grant an amnesty to people in exile. Dante was on the list of citizens to be pardoned, but Florence required that in addition to paying a sum of money, these citizens agree to be treated as public offenders in a religious ceremony. Dante refused this outrageous formula, preferring to remain in exile.

Dante still hoped late in life that he might be invited back to Florence on honorable terms. For Dante, exile was akin to a form of death, stripping him of much of his identity. Dante addresses the pain of exile in Canto XVII (55-60) of Paradiso, where Cacciaguida, his great-great-grandfather, warns him what to expect:

- . . . Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta

- più caramente; e questo è quello strale

- che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta.

- Tu proverai sì come sa di sale

- lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle

- lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale . . .

- ". . . You shall leave everything you love most:

- this is the arrow that the bow of exile

- shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste

- of others' bread, how salt it is, and know

- how hard a path it is for one who goes

- ascending and descending others' stairs . . ."

As for the hope of returning to Florence, he describes it wistfully, as if he had already accepted its impossibility, in Canto XXV of Paradiso (1-9):

- Se mai continga che 'l poema sacro

- al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra,

- sì che m'ha fatto per molti anni macro,

- vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra

- del bello ovile ov'io dormi' agnello,

- nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra;

- con altra voce omai, con altro vello

- ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte

- del mio battesmo prenderò 'l cappello . . .

- If it ever come to pass that the sacred poem

- to which both heaven and earth have set their hand

- so as to have made me lean for many years

- should overcome the cruelty that bars me

- from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb,

- an enemy to the wolves that make war on it,

- with another voice now and other fleece

- I shall return a poet and at the font

- of my baptism take the laurel crown...

Dante would never return to Florence. Prince Guido Novello da Polenta invited him to Ravenna in 1318. He finished his epic poem there, dying in 1321 at the age of 56 while on the way back to Ravenna from a diplomatic mission in Venice, perhaps of malaria. Dante was buried in the Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called San Francesco). Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice, in 1483 took care of his remains by organizing a better tomb.

On the grave are inscribed some verses of Bernardo Canaccio, a friend of Dante, dedicated to Florence:

- parvi Florentia mater amoris

- "Florence, mother of little love"

Eventually, Florence came to regret Dante's exile. In 1829, a tomb was built for him in Florence in the basilica of Santa Croce. That tomb has been empty ever since, as Dante's body still remains in its tomb in Ravenna, far from the land he loved so dearly, but which never let him return home.

Works

La Vita Nuova

La Vita Nuova contains 42 brief chapters with commentaries on 25 sonnets, one ballata, and four canzoni; one canzone is left unfinished, interrupted by the death of Beatrice Portinari, Dante's life long love to whom all of the poems in the volume are dedicated.

Dante's commentaries explicate each poem, placing it within the context of his life. They present a frame story, which is not apparent within the sonnets themselves. The frame story is simple enough: it recounts the time from Dante's first sight of Beatrice when he was nine and she eight all the way to Dante's mourning her death, and his determination to write of her "that which has never been written of any woman".

Each separate section of commentary further refines the poet's concept of romantic love as the initial step in a spiritual development that results in the capacity for divine love. Dante's unusual approach to his piece — drawing upon personal events and experience, addressing the readers, and writing in the vernacular rather than Latin — marked a turning point in European poetry, encouraging many writers to abandon highly stylized forms of writing for a simpler one.

Themes and Contexts

Dante wrote the work at the suggestion of his friend, the poet Guido Cavalcanti. Each chapter typically consists of three parts, the autobiographical narrative, the resulting lyric that arose from those circumstances, and an analysis of the subject matter of the lyric.

Though the result is a landmark in the development of emotional autobiography (the most important advance since Saint Augustine's Confessions in the 5th century), like all medieval literature it is far removed from the modern autobiographical impulse. Moderns think that their own personalities, motivations, actions and acquaintances are interesting. None of that is of concern to Dante. What was interesting to him, and his audience, were the emotions of noble love, how they develop, how they are expressed in verse, and how they reveal the permanent intellectual truths of the divinely created world, how, that is, love can confer blessing on the soul and bring it close to God.

Appropriately, therefore, the work does not contain any proper name, except that of Beatrice herself. Not even her surname is given, or any details that would assist readers to identify her among the many ladies of Florence: only the name "Beatrice", because that was both her actual given name and her symbolic name as the conferrer of blessing. Dante does not name himself. He refers to Guido Cavalcanti only as "the first of my friends", to his own sister as "a young and noble lady ... who was related to me by the closest consanguinity", to Beatrice's brother similarly as one who "was so linked in consanguinity to the glorious lady that no-one was closer to her". The effect is that the reader cannot, as in a modern autobiography or novel, be distanced from the characters as one is distanced from one's own acquaintances. Instead, the reader is invited into the very emotional turmoil and lyric struggle of the unnamed author's own mind, and all the surrounding people in his story are seen in their relations to that mind.

There have been a variety of interpretations of La Vita Nuova. Among them is that of Mark Musa who claims that rather than a serious autobiographical exploration of Love, La Vita Nuova is "a cruel commentary on the youthful lover" that points out the "foolishness and shallowness of his protagonist, a self-centered and self-pitying youth." Regardless of whatever Dante's true purpose in writing it was, La Vita Nuova is essential for understanding the context of his other works- principally The Divine Comedy.

The Divine Comedy

The Divine Comedy describes Dante's journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso), guided first by the Roman epic poet Virgil and then by his beloved Beatrice. While the vision of Hell, the Inferno, is vivid for modern readers, the theological nuances presented in the other books require a certain amount of patience and scholarship to understand. Purgatorio, the most lyrical and human of the three, also has the most poets in it; Paradiso, the most heavily theological, has the most beautiful and ecstatic mystic passages, in which Dante tries to describe what he confesses he is unable to convey.

Dante wrote the Comedy in his regional dialect. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression, and simultaneously established the Tuscan dialect as the standard for Italian. In French, Italian is nicknamed la langue de Dante. It often confuses readers that such a serious work would be called a "Comedy". In Dante's time, all serious scholarly works were written in Latin (a tradition that would persist for many hundreds of years more, until the waning years of the Enlightenment,) and works written in any other language were assumed to be comedic in nature.

The Divine Comedy is notable not just for its content, although that in itself is revolutionary. Dante is the first major poet to write an epic in the Christian tradition, and in so doing he demonstrated the durability of Biblical figures (such as Heaven and Hell, Satan and God) for telling stories of great drama and intrigue. Moreover, he is one of the first poets, major or otherwise, to tell a story not of heroes and battles but of personal crisis and introspection. Dante's ideal guide through Purgatory and Heaven is his true love, Beatrice; and in many ways it was through Dante that the ideal of a true, romantic love would come to permeate Western culture.

The Divine Comedy is also notable for its poetic techniques. For the poem, Dante invented a very simple but extremely powerful rhyme scheme called terza rima, where the poem is broken up into three-line tersets which rhyme as follows:

- a

- b

- a

- b

- c

- b

- c

- d

- c

The rhyme scheme of the Divine Comedy (which is, sadly, difficult to reproduce in English without sounding forced) gives the reader a sense of onward movement — each terset introduces a new rhyme — while at the same time continuing with rhymes seen from the previous terset, creating a sense of gradual progress much like Dante's description of his gradual ascent through the worlds of the afterlife. Terza rima has become so closely associated with Dante that the mere use of it is often enough to indicate that a poet is alluding to Dante's works.

Other Works

Other works of Dante include Convivio ("The Banquet"), a collection of poems and interpretive commentary; Monarchia, which sets out Dante's ideas on global political organization; De vulgari eloquentia ("On the Eloquence of Vernacular"), on vernacular literature.

See also

- Asteroid 2999 Dante, named after the poet

- The Divine Comedy

- For potential allusions to Dante in Bob Dylan's oeuvre, see "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" ("I saw a black branch with blood that kept dripping . . .", cf. Inferno XIII) and "Tangled Up in Blue" ("then she opened up a book of poems and handed it to me, written by an Italian poet from the thirteenth century . . .").

Published Resources

- Bonghi, Giuseppe. Glossario de Italiano Medioevale.

- Riccardo, Merlante. Dizionario della Divina Commedia. A dictionary of words used by Dante. Medieval Italian and Modern Italian.

- Gustarelli, Andrea. Dizionario Dantesco, per lo studio della Divina Commedia. Casa Editrice Malfasi, 1946. A dictionary of those words in the Divine Comedywhose meaning in Medieval Italians differs from that in Modern Italian.

External links

- "Digital Dante" – A resource page dedicated to Dante and his works.

- The Princeton Dante Project

- The Dartmouth Dante Project

- Danteworlds at UT Austin

- Read Dante Alighieri's works on Read Print – Free books for students, teachers, and the classic enthusiast.

- Henry Holiday's 'Dante and Beatrice'

- "Dante Alighieri on the Web", about his life, time, and (complete) work.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- English translation of The Comedy by Anthony LaPorta

- Società Dantesca Italiana (bilingual site) contains among other info a database of all the earliest manuscripts of Dante's works, with (for some) transcription of the text and page images

- Guardian Books "Author Page", with profile and links to further articles.

- Dante Alighieri - The Divine Comedy

- Dante Ravenna Tomb

- Dante Cenotaph Tomb

Dante Societies around the World

- Head Office - Rome Dante Alighieri Society

- Sydney Dante Alighieri Society

- Massachusetts Dante Alighieri Society

- Paris Dante Alighieri Society

- Vienna Dante Alighieri Society

- Berlin Dante Alighieri Society

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.