|

|

| (77 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{Started}} | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

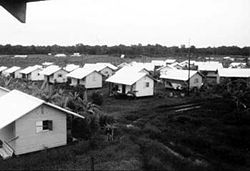

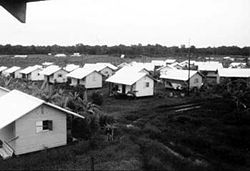

| | + | [[Image:Jonestown Houses.jpg|thumb|250px|Jonestown, Guyana, site of the Peoples Temple massacre in 1984]] |

| | | | |

| − | {{articleissues

| + | A '''cult,''' strictly speaking, is a particular system of religious [[worship]], especially with reference to its rites and ceremonies. Used in a more pejorative sense, cult refers to a cohesive social group, usually of a religious believers, which the surrounding society considers outside the mainstream or possibly dangerous. In [[Europe]], the term "[[sect]]" is often used to describe "cults" in this sense. |

| − | |OR=December 2006

| |

| − | |long=December 2006}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | : ''This article does not discuss "cult" in its original sense of "religious practice;" for that usage see [[Cult (religious practice)]]. See [[Cult (disambiguation)]] for more meanings of the term "cult."''

| + | During the twentieth century, groups referred to as "cults" or "sects" by governments and media became globally controversial. The rise and fall of several groups known for mass [[suicide]] and murder tarred hundreds of new religious groups of various characters, some arguably quite benign. Charges of "[[mind control]]," economic exploitation, and other forms of a abuse are routinely levied against "cults." However, scholars point out that each group is unique, and generalizations often do a disservice to the understanding of any particular group. |

| − | | + | {{toc}} |

| − | '''Cult''' inexactly refers to a cohesive social group devoted to beliefs or practices usually contrary to the norms of democracy (e.g. equality of the sexes, men and women may hold positions of authority in the group equally) or other rules and beliefs that the surrounding culture considers outside the mainstream or even unlawful. Cults may have a notably positive or negative popular perception. In common or populist usage, "cult" has a positive connotation for groups of artistic and fashion devotees, but a negative connotation for new religious or extreme political movements. For this reason, most, if not all, religious and political groups that are called cults reject this label.

| + | Controversy exists among sociologists of religion as to whether the term "cult" should be abandoned in favor of the more neutral "[[new religious movement]]." A great deal of literature has been produced on the subject, the objectivity of which is hotly debated. |

| − | | |

| − | A group's populist cult status begins as rumors of its novel belief system, its great devotions, its idiosyncratic practices, its perceived harmful or beneficial effects on members, or its perceived opposition to the interests of mainstream cultures and governments. Cult rumors most often refer to artistic and fashion movements of passing interest, but persistent rumors escalate popular concern about relatively small and recently founded religious movements, or non-religious groups, perceived to engage in excessive member control or exploitation.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some [[anthropologists]] and [[sociologists]] studying cults have argued that no one has yet been able to define “cult” in a way that enables the term to identify only groups that have been identified as problematic. However, without the "problematic" concern, scientific criteria of characteristics attributed to cults do exist.<ref>Robert J. Lifton, 1961, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism <small>(cited by freedomofmind.com)</small></ref> A little-known example is the Alexander and Rollins, 1984, scientific study concluding that the socially well-received group [[Alcoholics Anonymous]] is a cult,<ref>Alexander, F., Rollins, R. (1984). “Alcoholics Anonymous: The Unseen Cult,” California Sociologist, Vol. 7, No. 1, Winter, page 32 as cited in Ragels, L. Allen "Is Alcoholics Anonymous a Cult? An Old Question Revisited" “AA uses all the methods of brain washing, which are also the methods employed by cults ... It is our contention that AA is a cult.” transcribed to Freedom of Mind, website and retrieved on August 23, 2006. </ref> yet Vaillant, 2005, further concluded that AA is beneficial. <ref> Vaillant, 2005, concluded that AA "..appears equal to or superior to conventional treatments for alcoholism,..." and "...is probably without serious side-effects." Vaillant GE. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;39(6):431-6. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15943643&dopt=Abstract Pubmed abstract PMID: 15943643]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Laypersons participate in cultic studies to a degree not found in other academic disciplines, making it difficult to demarcate the boundaries of science from theology, politics, news reporting, fashion, and family cultural values. From about 1920 onward, the populist negative connotation progressively interfered with scientific study using the neutral historical meaning of "cult" in the [[sociology of religion]]. <ref>"This popular use of the term has gained such credence and momentum that it has virtually swallowed up the more neutral historical meaning of the term from the [[sociology of religion]]" [[James Richardson (sociologist)|James T. Richardson]] wrote in 1993.</ref> A 20th century attempt by sociologists to replace "cult" with the term [[New Religious Movement]] (NRM), was rejected by the public <ref>"The use of the concept "new religious movements" in public discourse is problematic for the simple reason that it has not gained currency. Speaking bluntly from personal experience, when I use the concept "new religious movements," the large majority of people I encounter don't know what I'm talking about. I am invariably queried as to what I mean. And, at some point in the course of my explanation, the inquirer unfailing responds, "oh, you mean you study cults!" "—Prof. Jeffrey K. Hadden quoted from [http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/cultsect/concult.htm#scholar_v_public Conceptualizing "Cult" and "Sect"] <small>(cited by cultfaq.org)</small></ref> and only partly accepted by the scientific community. <ref>"...use of the term 'cult' by academics, the public and the mass media, from its early academic use in the sociology of religion to recent calls for the term to be abandoned by scholars of religion because it is now so overladen with negative connotations. But scholars of religion have a duty not to capitulate to popular opinion, media and governments in the arena of the 'politics of representation'. The author argues that we should continue using the term 'cult' as a descriptive technical term. It has considerable educational value in the study of religions.

| |

| − | "—Michael York quoted from [http://www.uni-marburg.de/religionswissenschaft/journal/diskus/york.html Defending the Cult in the Politics of

| |

| − | Representation] DISKUS Vol.4 No.2 (1996) <small>(cited by cultfaq.org)</small></ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | During the 20th century groups referred to as cults by governments and media became globally controversial. The televised rise and fall of less than 20 [[Destructive cults]] known for mass suicide and murder tarred hundreds of NRM groups having less serious government and civil legal entanglements, against a background of thousands of unremarkable NRM groups known only to their neighbors. Following the [[Solar Temple]] destructive cult incidents on two continents, France authorized the 1995 [[Parliamentary Commission on Cults in France]]. This commission set a mostly non-controversial standard for human rights objections to exploitative group practices, and mandated a controversial remedy for cultic abuse, known in English as ''cult watching'', which was quietly adopted by other countries. The United States responded with human rights challenges to French cult control policies, and France charged the U.S. with interferring in French internal affairs. In recent years, France's troublesome public cult watching lists appear to have been retired in favor of confidential police intelligence gathering.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==Definitions== | | ==Definitions== |

| − | The literal and traditional meaning of the word ''cult'' is derived from the [[Latin]] ''cultus,'' meaning "care" or "adoration."<ref>[[Merriam-Webster]] Online Dictionary entry for ''cult'' [http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=cult&]</ref> In English, "cult" remains neutral and a technical term within this context to refer to the "cult of [[Artemis]] at [[Ephesus]]" and the "cult figures" that accompanied it, or to "the importance of the ''Ave Maria'' in the cult of the [[Blessed Virgin Mary|Virgin]]."

| + | Etymologically, the word cult comes from the root of the word culture, representing the core system of beliefs and activities at the basis of a culture. Thus, every human being belongs to a "cult" in its most general sense, because everyone belongs to a culture which is conveyed by the language they speak and the habits they have formed. |

| − | | |

| − | In non-English European terms, the cognates of the English word "cult" are neutral, and refer mainly to divisions within a single faith, a case where English speakers might use the word "[[sect]]," as in "[[Roman Catholicism]], [[Eastern Orthodoxy]] and [[Protestantism]] are ''sects'' (or ''denominations'') ''within'' [[Christianity]]." In [[French language|French]] or [[Spanish language|Spanish]], ''culte'' or ''culto'' simply means "worship" or "religious attendance"; thus an ''association cultuelle'' is an association whose goal is to organize religious worship and practices.

| |

| − | | |

| − | By comparison, the non-English European cognates of "sect" mean what "cult" does in English: ''secte'' (French), ''secta'' (Spanish), ''sekta'' [[Russian language|Russian]], and ''Sekte'' (German) which also has other definitions.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Conservative Christian authors, especially [[Evangelicalism|evangelical]] [[Protestants]], define a cult as a religion which claims to be in conformance with Biblical truth, yet deviates from it. [[Walter Martin]], the pioneer of the [[Christian countercult movement]], gave in his 1955 book the following definition:<ref>Martin, Walter. ''The Rise of the Cults'' (1955), 11–12.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | <blockquote>By cultism we mean the adherence to doctrines which are pointedly contradictory to orthodox Christianity and which yet claim the distinction of either tracing their origin to orthodox sources or of being in essential harmony with those sources. Cultism, in short, is any major deviation from orthodox Christianity relative to the cardinal doctrines of the Christian faith.</blockquote>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Author [[Robert M. Bowman Jr.]] defines a cult as "A religious group originating as a heretical sect and maintaining fervent commitment to heresy," while noting that the adjective "cultic" can be applied to groups approaching this standard to varying degrees.<ref>Bowman, Robert M., ''A Biblical Guide To Orthodoxy And Heresy'', 1994, [http://apologeticsindex.org/d01.html]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Dictionary definitions of "cult"===

| |

| − | Dictionary definitions of the term "cult" include at least eight different meanings. These include both classic and unorthodox religious practice, extreme political practice, objects or concepts of intense devotion including popular fashion, and systems for the cure of disease based on dogmatic teachings.<ref>[[Merriam-Webster]] Online Dictionary entry for ''cult'' [http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=cult&]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Merriam-Webster online dictionary lists five different definitions of the word "cult."<ref>[[Merriam-Webster]] Online Dictionary entry for ''cult'' [http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=cult&]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ::1. Formal religious veneration

| |

| − | ::2. A system of religious beliefs and ritual; also: its body of adherents;

| |

| − | ::3. A religion regarded as unorthodox or spurious; also: its body of adherents;

| |

| − | ::4. A system for the cure of disease based on dogma set forth by its promulgator;

| |

| − | ::5. Great devotion to a person, idea, object, movement, or work (as a film or book).

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Random House Unabridged Dictionary's eight definitions of "cult" are:

| |

| − | | |

| − | ::1. A particular system of religious worship, esp. with reference to its rites and ceremonies;

| |

| − | ::2. An instance of great veneration of a person, ideal, or thing, esp. as manifested by a body of admirers;

| |

| − | ::3. The object of such devotion;

| |

| − | ::4. A group or sect bound together by veneration of the same thing, person, ideal, etc;

| |

| − | ::5. Group having a sacred ideology and a set of rites centering around their sacred symbols;

| |

| − | ::6. A religion or sect considered to be false, unorthodox, or extremist, with members often living outside of conventional society under the direction of a charismatic leader;

| |

| − | ::7. The members of such a religion or sect;

| |

| − | ::8. Any system for treating human sickness that originated by a person usually claiming to have sole insight into the nature of disease, and that employs methods regarded as unorthodox or unscientific.

| |

| − | | |

| − | For authoritative British usage, the Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English definitions of "cult" and "sect" are:

| |

| − | | |

| − | :cult <ref>[http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/cult?view=uk]</ref>

| |

| − | ::1 a system of religious worship directed towards a particular figure or object.

| |

| − | ::2 a small religious group regarded as strange or as imposing excessive control over members.

| |

| − | ::3 something popular or fashionable among a particular section of society.

| |

| − | | |

| − | :sect <ref>[http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/sect?view=uk]</ref>

| |

| − | ::1 a group of people with different religious beliefs (typically regarded as heretical) from those of a larger group to which they belong.

| |

| − | ::2 a group with extreme or dangerous philosophical or political ideas.

| |

| − | | |

| − | British "sect" formerly included a contextually implied meaning, of what "cult" now means

| |

| − | in both USA and the UK.<ref>Examples of contemporary British "cult" usage: [http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2006/05/18/uslave.xml&sSheet=/news/2006/05/18/ixnews.html Daily Telegraph]; [http://thescotsman.scotsman.com/international.cfm?id=978262002 Scotsman] Example of contemporary British "sect" usage: ''"Before beginning counselling the counsellor needs to be sure that it was indeed a cult and not a sect in which the person was enmeshed. A sect may be described as a spin-off from an established religion or quite eclectic, but it does not use techniques of mind control on its membership."''[http://www.cultinformation.org.uk/articles2.html Web site, UK-based], [[Cult Information Centre]]</ref> Some other nations still use the foreign equivalents of old British "sect" ("secte," "sekte," or "secta." etc.) to imply "cult."<ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sect#Corresponding_words_in_French.2C_Spanish.2C_German.2C_Polish.2C_Dutch.2C_and_Romanian]</ref> Both words, as well as "cult" in its original sense of [[Cult (religious practice)|cultus]] (e.g., Middle Ages ''cult of Mary''), must be understood to correctly interpret 20th century popular cult references in world English.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Sociological definitions of religion===

| |

| − | According to one common typology among sociologists, religious groups are classified as [[ecclesia (sociology of religion)|ecclesia]]s, [[religious denomination|denomination]]s, cults or [[sect]]s.

| |

| − | | |

| − | A very common definition in the sociology of religion for ''cult'' is one of the four terms making up the [[church-sect typology]]. Under this definition, a cult refers to a religious group with a high degree of tension with the surrounding society combined with novel religious beliefs. This is distinguished from sects, which have a high degree of tension with society but whose beliefs are traditional to that society, and ecclesias and denominations, which are groups with a low degree of tension and traditional beliefs.

| |

| − | | |

| − | According to [[Rodney Stark]]'s ''A Theory of Religion'', most religions start out their lives as cults or sects, i.e. groups in high tension with the surrounding society. Over time, they tend to either die out or become more established, mainstream and in less tension with society. Cults are new groups with a novel theology, while sects are attempts to return mainstream religions to what the group views as their original purity.<ref>Stark, Rodney and Bainbridge, Willia S. ''A Theory of Religion," Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-2330-3</ref> As set out by Stark and Bainbridge, the term "cult," is used distinctly among the general definitions, and is closely related to the historically changed definitions of "sect." In this contemporary view, a "sect" is specifically "a deviant religious organization with traditional beliefs and practices," as compared to a "cult" which indicates a "a deviant religious organization with novel beliefs and practices."<ref>[http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/cultsect/concult.htm#key%20concepts]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Since this definition of "cult" is defined in part in terms of tension with the surrounding society, the same group may both be and not a cult at different places or times. For example, Christianity was by this definition a cult in 1st and 2nd century Rome, while in fifth century Rome it became rather an ecclesia (the state religion). Similarly, very conservative Islam could constitute a cult in the West but also the ecclesia in some conservative Muslim countries. Likewise, because novelty of beliefs and tension are elements in the definition: the Hare Krishnas are not a cult but a sect in India (since their beliefs are largely traditional to Hindu culture), while they are by this definition a cult in the Western world (since their beliefs are largely novel to Christian culture).

| |

| − | | |

| − | The English sociologist [[Roy Wallis]]<ref>[[Eileen Barker|Barker, E]]. ''New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction'' (1990), Bernan Press, ISBN 0-11-340927-3</ref> argues that a cult is characterized "[[epistemology|epistemological]] individualism" by which he means that "the cult has no clear locus of final authority beyond the individual member." Cults, according to Wallis, are generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals, loosely structured, tolerant, non-exclusive," making "few demands on members," without possessing a "clear distinction between members and non-members," having "a rapid turnover of membership," and are transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief systems Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu." Wallis contrast a cult with a [[sect]] that he asserts are characterized by "epistemological authoritarianism": sects possess some authoritative locus for the legitimate attribution of heresy. According to Wallis, "sects lay a claim to possess unique and privileged access to the truth or salvation and their committed adherents typically regard all those outside the confines of the collectivity as 'in error'".<ref>Wallis, Roy ''The Road to Total Freedom A Sociological analysis of Scientology'' (1976) [http://whyaretheydead.net/krasel/books/wallis/wallis1.html available online (bad scan)]</ref><ref>Wallis, Roy ''Scientology: Therapeutic Cult to Religious Sect'' [http://soc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/9/1/89 abstract only] (1975)</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Psychological definition===

| |

| − | Studies of the psychological aspects of cults focus on the individual person, and factors relating to the choice to become involved as well as the subsequent effects on individuals. Under one view, an important factor is [[coercive persuasion]] which suppresses the ability of people to reason, think critically, and make choices in their own best interest.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Studies of religious, political, and other cults have identified a number of key steps in this type of coercive persuasion: <ref>Galanter, 1989; Mithers, 1994; Ofshe & Watters, 1994; Singer, Temerlin, & Langone, 1990; Zimbardo & leipper, 1991</ref> 1. People are put in physically or emotionally distressing situations; 2. their problems are reduced to one simple explanation, which is repeatedly emphasized; 3. they receive unconditional love, acceptance, and attention from the leader; 4. they get a new identity based on the group; 5. they are subject to entrapment and their access to information is severely controlled.<ref>Psychology 101, Carole Wade et al., 2005</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Definition of 'cult' according to secular opposition===

| |

| − | Secular cult opponents tend to define a "cult"

| |

| − | as a religious or non-religious group that tends to manipulate, exploit, and control its members. Specific factors in cult behavior are said to include manipulative and authoritarian [[mind control]] over members, communal and totalistic organisation, aggressive proselytizing, systematic programs of indoctrination, and perpetuation in middle-class communities.<ref>T. Robbins and D. Anthony (1982:283, quoted in Richardson 1993:351) ("...certain manipulative and authoritarian groups which allegedly employ mind control and pose a threat to mental health are universally labeled cults. These groups are usually 1) authoritarian in their leadership; 2)communal and totalistic in their organization; 3) aggressive in their proselytizing; 4) systematic in their programs of indoctrination; 5)relatively new and unfamiliar in the United states; 6)middle class in their clientele")</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | While acknowledging the issue of multiple definitions of "cult",<ref>[http://www.csj.org/infoserv_articles/langone_michael_term_cult_definitional_ambiquity.htm The Definitional Ambiguity of "Cult" and ICSA’s Mission]</ref> [[Michael Langone]] states that "Cults are groups that often exploit members psychologically and/or financially, typically by making members comply with leadership's demands through certain types of psychological manipulation, popularly called ''mind control'', and through the inculcation of deep-seated anxious dependency on the group and its leaders."<ref>William Chambers, Michael Langone, Arthur Dole & James Grice, ''The Group Psychological Abuse Scale: A Measure of the Varieties of Cultic Abuse'', ''Cultic Studies Journal'', 11(1), 1994. The definition of a cult given above is based on a study of 308 former members of 101 groups.</ref> A similar definition is given by [[Louis Jolyon West]]:

| |

| − | | |

| − | : ''"A cult is a group or movement exhibiting a great or excessive devotion or dedication to some person, idea or thing and employing unethically manipulative techniques of persuasion and control (e.g. isolation from former friends and family, debilitation, use of special methods to heighten suggestibility and subservience, powerful group pressures, information management, suspension of individuality or critical judgement, promotion of total dependency on the group and fear of [consequences of] leaving it, etc) designed to advance the goals of the group's leaders to the actual or possible detriment of members, their families, or the community." ''<ref>[[Louis Jolyon West|West, L. J.]], & Langone, M. D. (1985). ''Cultism: A conference for scholars and policy makers. Summary of proceedings of the Wingspread conference on cultism, September 9–11''. Weston, MA: American Family Foundation.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In each, the focus tends to be on the specific tactics of conversion, the negative impact on individual members, and the difficulty in leaving once indoctrination has occurred.<ref>A discussion and list of ACM (anti-cult movement) groups can be found at [http://www.religioustolerance.org/acm.htm http://www.religioustolerance.org/acm.htm].</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Christianity and definitions of "cults"===

| |

| − | Since at least the 1940s, the approach of orthodox, conservative, or [[fundamentalist]] Christians was to apply the meaning of ''cult'' such that it included those religious groups who used (possibly exclusively) non-standard translations of the Bible, put additional [[revelation]] on a similar or higher level than the Bible, or had beliefs and/or practices deviant from those of traditional Christianity. <ref>Some examples of sources (with published dates where known) that documented this approach are:

| |

| − | | |

| − | * ''Heresies and Cults'', by J. Oswald Sanders, pub. 1948.

| |

| − | * ''Cults and Isms'', by J. Oswald Sanders, pub. 1962, 1969, 1980 (Arrowsmith), ISBN 0-551-00458-4.

| |

| − | * ''Chaos of the Cults'', by J.K. van Baalen.

| |

| − | * ''Heresies Exposed'', by W.C. Irvine.

| |

| − | * ''Confusion of Tongues'', by C.W. Ferguson.

| |

| − | * ''Isms New and Old'', by Julius Bodensieck.

| |

| − | * ''Some Latter-Day Religions'', by G.H. Combs.

| |

| − | * ''The Kingdom of the Cults'', by Walter Martin, Ph.D., pub. 1965, 1973, 1977, ISBN 0-87123-300-2</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Differing opinions of the various definitions==

| |

| − | According to professor [[Timothy Miller]] from the [[University of Kansas]] in his 2003 ''Religious Movements in the United States'', during the controversies over the new religious groups in the 1960s, the term "cult" came to mean something sinister, generally used to describe a movement at least potentially destructive to its members or to society. But he argues that no one yet has been able to define a "cult" in a way that enables the term to identify only problematic groups. Miller asserts that the attributes of groups often referred to as cults (see [[cult checklist]]), as defined by cult opponents, can be found in groups that few would consider cultic, such as [[Catholic]] religious orders or many [[evangelicalism|evangelical]] [[Protestant]] churches. Miller argues:

| |

| − | <blockquote>

| |

| − | If the term does not enable us to distinguish between a pathological group and a legitimate one, then it has no real value. It is the religious equivalent of the racial term for African Americans—it conveys disdain and prejudice without having any valuable content.<ref>[[Timothy Miller|Miller, Timothy]], ''Religious Movements in the United States: An Informal Introduction'' (2003) [http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/essays/miller2003.htm]</ref>

| |

| − | </blockquote>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Due to the usually pejorative connotation of the word "cult," new religious movements (NRMs) and other purported cults often find the word highly offensive.{{Fact|date=August 2007}} Some purported cults have been known to insist that other similar groups are cults but that they themselves are not. On the other hand, some [[Skepticism|skeptics]] have questioned the distinction between a cult and a mainstream religion, saying that cults only differ from recognized [[religion]]s in their history and the societal familiarity with recognized religions which makes them seem less controversial.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Study of cults==

| |

| − | {{OR}}

| |

| − | Among the experts studying cults and new religious movements are sociologists, religion scholars, psychologists, and psychiatrists. To an unusual extent for an academic/quasi-scientific field, however, nonacademics are involved in the study of and/or debates concerning cults, especially from the "anti-cult" point of view.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} These include investigative journalists and nonacademic book authors who have sometimes examined court records and studied the finances of groups, writers who once were members of purported cults, and professionals such as therapists who work with ex-members of groups referred to cults. Less widely known are the writings by members of organizations that have been labelled cults, defending their organizations and replying to critics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Nonacademics are sometimes published, or their writings cited, in the ''Cultic Studies Journal'' ''(CSJ)'', the journal of the [[International Cultic Studies Association]] (ICSA), a group which criticizes perceived cultic behavior. Sociologist Janja Lalich began her work and conceptualized many of her ideas while an "anti-cult" activist writing for the "CSJ" years before obtaining academic standing, and incorporated her own experiences in a leftwing political group into her later work as a sociological theorist.{{Fact|date=July 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | The hundreds of books on specific groups by nonacademic comprise a large portion of the currently available published record on cults. The books by "anti-cult" critics run from memoirs by ex-members to detailed accounts of the history and alleged misdeeds of a given group written from either a tabloid journalist, investigative journalist, or popular historian perspective.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Journalists [[Flo Conway]] and [[Jim Siegelman]] together wrote the book ''[[Snapping]]'', which set forth speculations on the nature of mind control that have received mixed reviews from psychologists. Others mentioned in this article include Tim Wohlforth (co-author of ''On the Edge'' and a former follower of British Trotskyist [[Gerry Healy]]); Carol Giambalvo, a former [[Erhard Seminars Training|est]] member; activist and consultant [[Rick Ross (consultant)|Rick Ross]]; and mental health counselor [[Steven Hassan]], a former [[Unification Church]] member and author of the book ''[[Combatting Cult Mind Control]]'', who, like Ross, runs a business specializing in servicing people involved with cults or their family members.[http://www.rickross.org/help.html][http://www.freedomofmind.com/stevehassan/fees/] Another example is the work of journalist/activist [[Chip Berlet]], responsible for much of the work on "political cults" which exists today. Current members of the [[Hare Krishna]] movement as well as several former leaders of the [[Worldwide Church of God]] also have written with critical insight on "cult" issues, using terminologies and framings somewhat different from those of secular experts. Members of the Unification Church have produced books and articles that argue the case against excessive reactions to new religious movements, including their own.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Within this larger community of discourse, the debates about "cultism" and specific groups are generally more polarized than among scholars who study new religious movements, although there are heated disagreements among scholars as well. What follows is a summary of that portion of the intellectual debate conducted primarily from inside the universities:

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Cults, NRMs, and the sociology and psychology of religion===

| |

| − | Due to popular connotations of the term "cult," many academic researchers of [[religion]] and [[sociology]] prefer to use the term ''[[new religious movement]]'' (NRM) in their research. However, some researchers have criticized the newer phrase on the ground that some religious movements are "new" without being cults, and have expanded the definition of cult to non-religious groups. Furthermore, some religious groups commonly regarded as cults are no longer "new"; for instance, [[Scientology]] and the [[Unification Church]] are both over 50 years old, while the [[Hare Krishna]] came out of [[Gaudiya Vaishnavism]], a religious tradition that is approximately 500 years old.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some mental health professionals use the term ''cult'' generally for groups that practice physical or mental abuse. Others prefer more descriptive terminology such as ''abusive cult'' or ''[[destructive cult]]'', while noting that noting that many groups meet the other criteria without such abuse. A related issue is determining what is abuse, when few members (as opposed to some ex-members) would agree that they have suffered abuse. Other researchers like [[David V. Barrett]] hold the view that classifying a religious movement as a cult is generally used as a subjective and negative label and has no added value; instead, he argues that one should investigate the beliefs and practices of the religious movement.<ref>Barrett, D. V. ''The New Believers - A survey of sects, cults and alternative religions'' 2001 UK, Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35592-5</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | According to the Dutch religious scholar [[Wouter Hanegraaff]], another problem with writing about cults comes about because they generally hold [[world view|belief system]]s that give answers to questions about the meaning of [[personal life|life]] and [[morality]]. This makes it difficult not to write in biased terms about a certain group, because writers are rarely neutral about these questions. Some admit this, and try to diffuse the problem by stating their personal sympathies openly.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the sociology of religion, the term cult is part of the subdivision of religious groups: sects, cults, denominations, and ecclesias. The sociologists [[Rodney Stark]] and William S. Bainbridge define cults in their book, [[Development of religion#"Theory of religion" model|"Theory of Religion"]] and subsequent works, as a "deviant religious organization with novel beliefs and practices," that is, as [[new religious movement]]s that (unlike [[sect]]s) have not separated from another religious organization. Cults, in this sense, may or may not be dangerous, abusive, etc. By this broad definition, most of the groups which have been popularly labeled cults fit this value-neutral definition.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Development of groups characterized as cults===

| |

| − | Cults based on charismatic leadership often follow the [[Charismatic authority#Routinizing charisma|routinization of charisma]], as described by the German sociologist [[Max Weber]]. In their book ''Theory of Religion'', [[Rodney Stark]] and [[William Sims Bainbridge]] propose that the formation of cults can be explained through a combination of four models:

| |

| − | | |

| − | * The '''psychopathological model''' - the cult founder suffers from psychological problems; they develop the cult in order to resolve these problems for themselves, as a form of self-therapy

| |

| − | * The '''entrepreneurial model''' - the cult founder acts like an entrepreneur, trying to develop a religion which they think will be most attractive to potential recruits, often based on their experiences from previous cults or other religious groups they have belonged to

| |

| − | * The '''social model''' - the cult is formed through a [[social implosion]], in which cult members dramatically reduce the intensity of their emotional bonds with non-cult members, and dramatically increase the intensity of those bonds with fellow cult members - this emotionally intense situation naturally encourages the formation of a shared belief system and rituals

| |

| − | * The '''normal revelations model''' - the cult is formed when the founder chooses to interpret ordinary natural phenomena as supernatural, such as by ascribing his or her own creativity in inventing the cult to that of the deity.

| |

| − | {{sectstub}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Leadership===

| |

| − | :''See also [[Development of religion#Role of charismatic figures in the development of religions|Role of charismatic figures in the development of religions'']]

| |

| − | | |

| − | According to Dr. [[Eileen Barker]], new religions are in most cases started by [[charismatic authority|charismatic]] but unpredictable leaders. According to Mikael Rothstein, there is often little access to plain facts about either historical or contemporary religious leaders to compare with the abundance of legends, [[mythology|myth]]s, and theological elaborations. According to Rothstein, most members of new religious movements have little chance to meet the ''Master'' (leader) except as a member of a larger audience.

| |

| − | {{sectstub}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Theories about joining cults and NRMs===

| |

| − | Michael Langone gives three different models regarding joining a cult. Under the "deliberative model," people are said to join cults primarily because of how they view a particular group. Langone notes that this view is most favored among sociologists and religious scholars. Under the "psychodynamic model," popular with some mental health professionals, individuals choose to join for fulfillment of subconscious psychological needs. Finally, the "thought reform model" posits that people join not because of their own psychological needs, but because of the group's influence through forms of psychological manipulation. Langone states that those mental health experts who have more direct experience with large number of cultists tend to favor this latter view.<ref>[[Michael Langone|Langone, Michael]], ''"Clinical Update on Cults"'', Psychiatric Times July 1996 Vol. XIII Issue 7 [http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/p960714.html]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Jeffrey Hadden summarizes a lecture entitled "Why Do People Join NRMs?" (a lecture in a series related to the sociology of new religious movements)<ref>Hadden, Jeffrey K. ''SOC 257: New Religious Movements Lectures'', University of Virginia, Department of Sociology.</ref> as follows:

| |

| − | | |

| − | # Belonging to groups is a natural human activity;

| |

| − | # People belong to religious groups for essentially the same reasons they belong to other groups;

| |

| − | # Conversion is generally understood as an emotionally charged experience that leads to a dramatic reorganization of the convert's life;

| |

| − | # Conversion varies enormously in terms of the intensity of the experience and the degree to which it actually alters the life of the convert;

| |

| − | # Conversion is one, but not the only reason people join religious groups;

| |

| − | # Social scientists have offered a number of theories to explain why people join religious groups;

| |

| − | # Most of these explanations could apply equally well to explain why people join lots of other kinds of groups;

| |

| − | # No one theory can explain all joinings or conversions;

| |

| − | # What all of these theories have in common (deprivation theory excluded) is the view that joining or converting is a natural process.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some scholars favor one particular view, or combine elements of each. According to Gallanter,<ref>Galanter, Marc [[M.D.]](Editor), (1989), ''Cults and new religious movements: a report of the committee on psychiatry and religion of the [[American Psychiatric Association]]'', ISBN 0-89042-212-5</ref> typical reasons why people join cults include a search for community and a spiritual quest. Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals join new religious groups, have questioned the utility of the concept of ''conversion'', suggesting that ''affiliation'' is a more useful concept.<ref>Bader, Chris & A. Demaris, ''A test of the Stark-Bainbridge theory of affiliation with religious cults and sects.'' Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35, 285-303. (1996)</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Relationships with the "outside world"===

| |

| − | Barker wrote that peripheral members may help to lessen the tension between some groups and the outside world. <sup>[[Cult#References|27]]</sup> Where members live in [[intentional community|intentional communities]], custody disputes (if one parent leaves and one stays) may be another source of confrontation between the cult and the outside world.

| |

| − | | |

| − | A cult need not necessarily operate outside of mainstream society to engage in 'cult' behaviour. Any demanded belief, expected to be held by members of the group, religion or organisation, which contradicts the articles of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights may find itself being described as a 'cult'. This is now a problem for mainstream religions in secular western democracies which hold values and maintain membership practices that are contrary to democratic secular values and laws. e.g. Islam and the practice of women covering themselves in public, ordination being restricted to men in the Catholic church and the traditional religious condemnation of homosexuality. These religious contraventions of human rights are becoming less tolerated and are more and more being acknowledged as 'cult' behaviors.

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{sectstub}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Reactions to social out-groups===

| |

| − | One issue in the study of cults relates to people's reactions to groups identified as some other form of social outcast or opposition group. A new study by Princeton University psychology researchers Lasana Harris and Susan Fiske shows that when viewing photographs of social out-groups, people respond to them with disgust, not a feeling of fellow humanity. The findings are reported in the article "Dehumanizing the Lowest of the Low: Neuro-imaging responses to Extreme Outgroups" in a forthcoming issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science (previously the American Psychological Society).<ref>[http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2006-06/afps-dpi062906.php]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | According to this research, social out-groups are perceived as unable to experience complex human emotions, share in-group beliefs, or act according to societal norms, moral rules, and values. The authors describe this as "extreme discrimination revealing the worst kind of prejudice: excluding out-groups from full humanity." Their study provides evidence that while individuals may consciously see members of social out-groups as people, the brain processes social out-groups as something less than human, whether we are aware of it or not. According to the authors, brain imaging provides a more accurate depiction of this prejudice than the verbal reporting usually used in research studies.

| + | [[Image:OurLady.jpg|thumb|150px|The traditional use of the word "cult" refers to any tradition of religious worship, such as the cult of the Virgin Mary in Catholicism.]] |

| | + | The literal and traditional meaning of the word ''cult'' is derived from the [[Latin]] ''cultus,'' meaning "care" or "adoration." Sociologists and historians of religion speak of the "cult" of the [[Virgin Mary]] or other traditions of worship in a neutral sense. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Genuine concerns and exaggerations about "cults"===

| + | Among the formal definitions of "cult" are: |

| − | Some critics of media sensationalism argue that the stigma surrounding the classification of a group as a cult results largely from exaggerated portrayals of weirdness in media stories. The narratives of ill effects include perceived threats presented by a cult to its members, and risks to the ''physical'' safety of its members and to their mental and ''spiritual'' growth.

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Anti-Cult Movement|Anti-cultists]] in the 1970s and 1980s made heavy accusations regarding the harm and danger of cults for members, their families, and societies. The debate at that time was intense and was sometimes called the ''cult debate'' or ''cult wars''.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | + | * A particular system of religious worship, esp. with reference to its rites and ceremonies. |

| | + | * An instance of great veneration of a person, ideal, or thing, especially as manifested by a body of admirers: The physical fitness cult. |

| | + | * A group or sect bound together by veneration of the same thing, person, ideal, and so on. |

| | + | * In [[Sociology]]: A group having a sacred ideology and a set of rites centering around their sacred symbols. |

| | + | * A religion or sect considered to be false, unorthodox, or extremist, with members often living outside of conventional society under the direction of a charismatic leader.<ref>[http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/cult Cult,] Dictionary.com. Retrieved August 23, 2008.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Much of the action taken against cults has been in reaction to the real or perceived harm experienced by some members.

| + | Most religions start out as "cults" or sects in the sense of the pejorative use of the term, that is, relatively small groups in high tension with the surrounding society. The classical example is [[Christianity]]. When it began, it was a minority system of beliefs and controversial practices such as [[holy communion]]. When it was a small "cult" or a minority group in the empire, it was often criticized by those who did not understand it or who were threatened by changes its adoption might mean. Rumors were spread by detractors about Christians drinking human blood and eating human flesh. However, when it became an official state religion and widely accepted, its practices informed activities of the culture as a whole. |

| | + | When a new religion becomes a large or dominant in a society the "cult" basically becomes "culture."<ref>Peter L. Berger, ''The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion'' (New York: Doubleday Anchor Books 1969), 29-51.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | ====Documented crimes====

| + | In this sense, "cult" may be seen as a pejorative term, something akin to calling someone a "[[barbarian]]." It represents a type of in-group/out-group terminology designed to exclude one group by calling them less human or inferior. Over time, such groups tend either die to out or become more established and in less tension with society.<ref>Stark, 1996.</ref> |

| − | [[Image:Jim Jones brochure of Peoples Temple.jpg|thumb|200px|Brochure of the [[Peoples Temple]], portraying its founder [[Jim Jones]] as the loving father of the "Rainbow Family".</sup>]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | Certain groups that have been characterized as cults, such as [[Heaven's Gate (cult)|Heaven's Gate]], [[Order of the Solar Temple|Ordre du Temple Solaire]], [[Aum Shinrikyo]], the [[Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God]] in Uganda, the [[Church of the Lamb of God]] of [[Ervil LeBaron]], and the [[Peoples Temple]] have posed or are seen as potentially posing a threat to the well-being and lives of their own members and to society in general. These organizations are often referred to as ''doomsday cults'' or ''[[destructive cult]]''s by the media. According to John R. Hall, a professor in sociology at the [[University of California-Davis]] and Philip Schuyler, the Peoples Temple is still seen by some as ''the'' cultus classicus<ref>Hall, John R. and Philip Schuyler (1998), ''Apostasy, Apocalypse, and religious violence: An Exploratory comparison of Peoples Temple, the Branch Davidians, and the Solar Temple'', in the book ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements'' edited by David G. Bromley Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, (1998). ISBN 0-275-95508-7, page 145 "The tendency to treat Peoples Temple as the ''cultus classicus'' headed by Jim Jones, psychotic megaliomanic par excellence is still with us, like most myths, because it has a grain of truth to it. "</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>McLemee, Scott ''Rethinking Jonestown '' on the [[salon.com]] website "If Jones' People's Temple wasn't a cult, then the term has no meaning."</ref>, though it did not belong to the set of groups that triggered the cult controversy in United States in the 1970s. Its mass suicide of over 900 members on November 18, 1978 led to increased concern about cults. Other groups include the [[Colonia Dignidad]] cult (a German group settled in Chile) that served as a torture center for the Chilean government during the Pinochet dictatorship.

| + | Due to popular connotations of the term "cult," many academic researchers of [[religion]] and [[sociology]] prefer to use the term ''[[new religious movement]]'' (NRM). Such new religions are usually started by [[charismatic authority|charismatic]] but unpredictable leaders. If they survive past the first or second generation, they tend to institutionalize, become more stable, find a greater degree of acceptance in society, and sometimes become a mainstream or even dominant religious group. |

| | | | |

| − | In 1984, a [[Bioterrorism|bioterrorist attack]] involving [[salmonella]] typhimurium contamination in the salad bars of 10 restaurants in [[The Dalles, Oregon|The Dalles]], [[Oregon]] was traced to the [[Rajneesh|Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh/Osho]] group.<ref>[http://www.wbur.org/special/specialcoverage/feature_bio.asp Bioterrorism in History - 1984: Rajneesh Cult Attacks Local Salad Bar], ''[[WBUR]]''</ref><ref>[http://www.rickross.org/reference/rajneesh/rajneesh8.html AP The Associated Press/October 19 2001</ref> The attack sickened about 751 people and hospitalized forty-five, although none died. It was the first known bioterrorist attack of the 20th century in the United States, and is still known as the largest germ warfare attack in U.S history. Eventually Sheela and Ma Anand Puja, one of Sheela's close associates, confessed to the attack as well as to attempted poisonings of county officials. The BW incident is used by the Homeland Defense Business Unit in Biological Incidents Operations training for Law Enforcement agencies.{{PDFlink|[http://www.edgewood.army.mil/hld/dl/ecbc_le_bio_guide.pdf]|934 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 957019 bytes —>}} | + | In Europe, the term "sect" tends to carry a connotation similar to the word "cult" in the U.S. |

| | | | |

| − | The [[Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway]] in 1995 was carried out by members of [[Aum Shinrikyo]], a religious group founded in 1984 by [[Shoko Asahara]]. Aum Shinrikyo had a laboratory in 1990 where they cultured and experimented with [[botulin toxin]], [[anthrax]], [[cholera]] and [[Q fever]]. In 1993 they traveled to Africa to learn about and bring back samples of the [[Ebola]] virus.[http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol5no4/olson.htm]

| + | ==Controversies about "cults"== |

| | + | By one measure, between 3,000 and 5,000 purported "cults" existed in the [[United States]] in 1995.<ref>Singer, 2003. |

| | + | </ref> [[Anti-Cult Movement|Anti-cult]] groups in the 1970s and 80s, overly comprised of families of NRM members who objected to the newfound faith of their relative, made particularly strong accusations regarding the threat of "dangerous cults." Among the allegations levied against these groups were "brainwashing," the separation of members from their families, food and sleep deprivation, economic exploitation, and potential harm to the larger society. Some families took desperate measures to force "cult" members back into traditional faiths or a secular way of life. This led to the so-called "[[deprogramming]]" controversy, in which thousands of young adults were forcibly kidnapped and held against their will by paid agents of family members in an effort to get them to renounce their groups. Media sensationalism fueled the controversy, as did court battles which pitted expert witnesses against each other in such fields as [[sociology]] and [[psychology]]. |

| | | | |

| − | Warren Jeffs, of Hildale, Utah, the polygamist sect leader of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, is currently charged with two counts of rape as an accomplice in the spiritual marriage of a 14-year-old girl to her 19-year-old cousin in 2001. Jeffs also faces felony sex charges in Arizona for his alleged role in two underage marriages, and was under federal indictment for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution as of March 2007.[http://www.cnn.com/2007/LAW/03/28/polygamist.leader.ap/index.html]

| + | [[Image:Aum-members.jpg|thumb|The Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attacks created renewed concern about destructive cults.]] |

| | | | |

| − | [[Edward Morrissey]], husband of [[Mary Manin Morrissey|Rev. Mary Manin Morrissey]], in 2005 pled guilty to [[money laundering]] and using [[Living Enrichment Center]] church money for the personal expenses of himself and his wife. Edward Morrissey spent two years in federal prison..<ref>[http://www.koin.com/Global/story.asp?s=6615206 KOIN 6 News] Retrieved June 7, 2007</ref><ref>http://www.oregonlive.com/oregonian/stories/index.ssf?/base/news/1181267788141050.xml&coll=7</ref><ref>[http://www.wilsonvillenews.com/WVSNews8.shtml Wilsonville Spokesman: Morrissey to meet with LEC 'refugees'] Retrieved June 9, 2007</ref> | + | Certain groups that have been characterized as cults have clearly posed a threat to the well-being and lives of their own members and to society in general. For example, the mass [[suicide]] of over 900 [[People's Temple]] members on November 18, 1978, led to increased concern about "cults." The [[sarin]] gas attack on the Tokyo subway in 1995, carried out by members of [[Aum Shinrikyo]], renewed this concern, as did several other violent acts—both self-destructive and against society—by other groups. The number of violently destructive groups, however, is extremely small compared with the literally tens of thousands of new religious movements which are estimated to exist.<ref>Barker, 1984.</ref> Thus, relatively harmless groups found themselves associated with the violent self-destructive "cult" actions in which they had no part. |

| | | | |

| − | ====Prevalence of doomsday or destructive cults====

| + | Today, some well-known NRM's remain suspect to the general public. Examples include [[Scientology]], the [[Unification Church]], and the [[Hare Krishnas]]. Each of these groups is now well into its second or third generation, but it is often difficult to distinguish between a group's public image—which may have become fixed decades earlier—and its current practices. Earlier "cults," such as the [[Mormon Church|Mormons]], [[Jehovah's Witnesses]], [[Seventh Day Adventist]]s, and [[Christian Scientists]], are now generally considered part of the mainstream religious fabric of the American society in which they originated. |

| − | It has been noted that despite the emphasis on "doomsday cults" by the media, the number of groups in this category is approximately ten, compared with the tens of thousands of new religious movements which are estimated to exist.<ref>[[Eileen Barker|Barker, E.]] (1984), ''[[The Making of a Moonie]]'', p.147, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13246-5</ref> (including groups that are psychologically destructive but not extremely violent or doomsday-oriented).

| |

| | | | |

| − | Of the groups that have been characterized as cults in the United States alone, only a hundred or so have ever become notorious for alleged misdeeds either in the national media or in local media. Some writers have argued that the disproportionate focus on these groups gives the public an inaccurate perception of new religious groups generally.{{Fact|date=July 2007}}

| + | Although the majority of "cults" are religious in nature, a small number of non-religious groups are classified as as "cults" by their opponents. These may include political, psychotherapeutic or [[multi-level marketing|marketing]] groups. The term has also been applied to certain human-potential and self-improvement organizations. |

| | | | |

| − | ====Potential harm to members==== | + | ===Stigmatization=== |

| − | In the opinion of [[Benjamin Zablocki]], a professor of Sociology at [[Rutgers University]], groups that have been characterized as cults are at high risk of becoming abusive to members. He states that this is in part due to members' adulation of [[charismatic authority|charismatic]] leaders contributing to the leaders becoming corrupted by power. Zablocki defines a cult here as an ideological organization held together by charismatic relationships and that demands total commitment.<ref>Dr. Zablocki, Benjamin [http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~zablocki/] Paper presented to a conference, ''Cults: Theory and Treatment Issues'', May 31 1997 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.</ref>

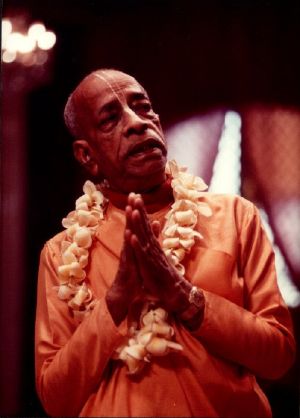

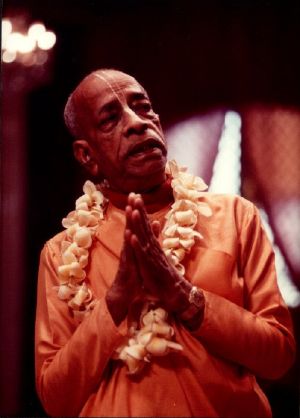

| + | [[Image:Swami Prabhupada.jpg|thumb|Swami Prabhupada, founder of the American movement for "Khrisha Consciousness."]] |

| | + | Because of the increasingly pejorative use of the terms "cult" over recent decades, many argue that the term should be avoided. |

| | | | |

| − | There is no reliable, generally accepted way to determine which groups will harm their members. In an attempt to predict the probability of harm, [[cult checklist]]s have been created, primarily by anti-cultists, for this purpose.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} <!-- Odd to call Bonewits, for instance, and anti-cultist, in that he was trying to promote his NRM, not all checklists are from anti-cultists!—!> <!-- Rephrased; hope it's better. —> According to critics of these checklists, they are popular but not scientific.

| + | Researcher [[Amy Ryan]] has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign.<ref>Amy Ryan, [http://rand.pratt.edu/~giannini/newreligions.html#Definitions New Religions and the Anti-Cult Movement.] Retrieved July 22, 2008.</ref> Ryan notes the sharp differences between definition from cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. These definitions of religion itself has political and ethical impact beyond scholarly debate. Washington DC legal scholar [[Bruce J. Casino]] presents the issue as crucial to international [[human rights]] law. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with [[freedom of religion]], while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."<ref>Bruce J. Casino, Defining Religion in American Law, ''Religious Freedom.''</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | According to Barrett, the most common accusation made against groups referred to as cults is [[sexual abuse]]. See [[Cult#Criticism by former members of purported cults|some allegations made by former members]]. According to Kranenborg, some groups are risky when they advise their members not to use regular medical care.<ref>Kranenborg, Reender Dr. (Dutch language) ''Sekten... gevaarlijk of niet?/Cults... dangerous or not?'' published in the magazine ''Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland/Religious movements in the Netherlands'' nr. 31 ''Sekten II'' by the [[Vrije Universiteit|Free university Amsterdam]] (1996) ISSN 0169-7374 ISBN 90-5383-426-5</ref> Barker, Barrett, and [[Steven Hassan]] all advise seeking information from various sources about a certain group before getting deeply involved, though these three differ in the urgency they suggest.

| + | In 1999, the [[Maryland]] State Task Force to Study the Effects of Cult Activities on Public Senior [[Higher Education]] Institutions admitted in its final report that it had "decided not to attempt to define the world 'cult'" and proceeded to avoid the word entirely in its final report, except in its title and introduction.<ref> Task Force Exectutive Summary, ''Religious Freedom.''</ref> |

| − | | |

| − | ====Other controversial groups====

| |

| − | Other groups, while not universally condemned, remain suspect to the general public; this is the case with [[Scientology]] and to a lesser extent, the [[Unification Church]] and the [[Hare Krishnas]]. A problem in casually examining such high-profile groups is to distinguish between a group's public image (which may have become fixed decades earlier) and the group's current practices. This is often a focus for empirical studies by social scientists. These issues arise especially for groups whose founders have died or that have splintered, or those with foreign origins gradually integrating themselves into the culture of a new country.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Non-religious groups characterized as cults===

| |

| − | According to the views of what some scholars call the "[[Anti-Cult Movement]]," although the majority of groups described as "cults" are religious in nature, a significant number are non-religious. These may include political, psychotherapeutic or [[Multi-level marketing|marketing]] oriented cults organized in manners similar to the traditional religious cult. The term has also been applied to certain channelling, human-potential and self-improvement organizations, some of which do not define themselves as religious but are considered to have significant religious influences.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Groups that have been labeled as "political cults," mostly far-left or far-right in their ideologies, have received some attention from journalists and scholars, though this usage is less common. Claims of cult-like practices exists for only about a dozen ideological cadre or racial combat organizations, though the allegation is sometimes made more freely.<ref>See Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth, ''[[On the Edge (book)|On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left]]'', Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000. [http://www.mesharpe.com/mall/resultsa.asp?Title=On+the+Edge%3A+Political+Cults+Right+and+Left]</ref> Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth are are two prominent former members of [[Trotskyist]] sects who now attack their former organizations and the Trotskyist movement in general.<ref>Bob Pitt, Review of Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth, On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left. ''What Next Journal'' (online), No. 17, 2000 [http://www.whatnextjournal.co.uk/Pages//Back/Wnext17/Reviews.html]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The concept of the "cult" is applied by analogy to refer to adulation of non-political leaders, and sometimes in the context of certain businessmen, management styles, and company work environments. [[Multi-level marketing]] has often been described as a cult due to the fact that a large part of the operation of a typical multi-level marketing consists of hiring and recruiting other people, selling motivational material, to the point that people involved in the business spend most of their time for the benefit of the organization. Consequently, some MLM companies like [[Amway]] have felt the need to specifically state that they are not cult-like in nature.<ref>{{cite web|title=Amway/Quixtar|publisher=Apologetics Index|url=http://www.apologeticsindex.org/a43.html|accessdate=2007-06-11}}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Another related term in politics is that of the [[personality cult]]. Although most groups labeled as [[political cult]]s involve a "[[cult of personality]]," the latter concept is a broader one, having its origins in the excessive adulation said to have surrounded Soviet leader [[Joseph Stalin]]. It has also been applied to several other despotic heads of state.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Stigmatization and discrimination==

| |

| − | Because of the increasingly pejorative use of the terms "cult" and "cult leader" over recent decades, many argue that these terms are to be avoided. A website affiliated with [[Adi Da Samraj]] sees the activities of cult opponents as the exercise of prejudice and discrimination against them, and regards the use of the words "cult" and "cult leader" as similar to political or racial epithets.<ref>[http://www.firmstand.org/]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Amy Ryan]] has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign.<ref>[[Amy Ryan]]: ''New Religions and the Anti-Cult Movement: Online Resource Guide in Social Sciences'' (2000) [http://rand.pratt.edu/~giannini/newreligions.html#Definitions]</ref> Ryan notes the sharp differences between definition from cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and those of sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. The movements themselves may have different definitions of religion as well. [[George Chryssides]] also cites a need to develop better definitions to allow for common ground in the debate.

| |

| − | | |

| − | These definitions have political and ethical impact beyond just scholarly debate. In ''Defining Religion in American Law'', Bruce J. Casino presents the issue as crucial to international human rights laws. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."<ref>Casino. Bruce J., ''Defining Religion in American Law'', 1999, [http://www.religiousfreedom.com/articles/casino.htm]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some authors in the cult opposition dislike the word cult to the extent it implies that there is a continuum with a large gray area separating "cult" from "noncult" which they do not see.<ref>Casino. Bruce J., ''Defining Religion in American Law'', 1999, [http://www.religiousfreedom.com/articles/casino.htm]</ref> Others authors, e.g. [[Steven Hassan]], differentiate by using terms like "[[Destructive cult]]," or "Cult" (totalitarian type) vs. "benign cult."

| |

| | | | |

| | ===Leaving a "cult"=== | | ===Leaving a "cult"=== |

| − | There are at least three ways people leave a "cult." These are 1.) On their own decision (walkaways); 2.) Through expulsion (castaways); and 3.) By intervention ([[Exit counseling]], [[deprogramming]]).<ref>Duhaime, Jean ([[Université de Montréal]]), ''Les Témoigagnes de Convertis et d'ex-Adeptes'' (English: ''The testimonies of converts and former followers'', an article which appeared in the book ''New Religions in a Postmodern World'' edited by Mikael Rothstein and Reender Kranenborg, RENNER Studies in New religions, [[Aarhus University]] press, 2003, ISBN 87-7288-748-6</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Giambalvo, Carol, ''Post-cult problems'' [http://www.csj.org/infoserv_articles/giambalvo_carol_postcult_problems.htm]</ref>

| + | A major contention of the anti-cult movement, in the 1970s, had been that "cult members" had lost their ability to choose and only rarely left their groups without "[[deprogramming]]." This view has been largely discredited, as there are clearly at least three ways people leave a new religious movement. These are 1) by their own decision, 2) through expulsion, and 3) by intervention ([[exit counseling]] or deprogramming). ("Exit counseling" is defined as a voluntary intervention in which the member agrees to the discussion and is free to leave. "Deprogramming" involves forcible confinement against the person's will.) |

| | | | |

| − | In ''Bounded Choice'' (2004), Lalich describes a fourth way of leaving—rebelling against the group's majority or leader. This was based on her own experience in the Marxist-Leninist Democratic Workers Party, where the entire membership quit. However, rebellion is more often a combination of the walkaway and castaway patterns in that the rebellion may trigger the expulsion—essentially, the rebels provoke the leadership into being the agency of their break with an over-committed lifestyle. Tourish and Wohlforth (2000) and Dennis King (1989) provide what they consider several examples in the history of political groups that have been characterized as cults. The 'rebellion' response in such groups appears to follow a longstanding behavior pattern among leftwing political sects which began long before the emergence of the contemporary political cult.

| + | Most authors agree that some people experience problems after leaving a "cult." These include negative reactions in the individual leaving the group as well as negative responses from the group such as [[shunning]], which is practiced by some but not all NRMs and older religions alike. There are disagreements regarding the degree and frequency of such problems, however, and regarding the cause. [[Eileen Barker]] mentions that some former members may not take new initiatives for quite a long time after disaffiliation from the NRM. However, she also points out that leaving is not nearly so difficult as imagined. Indeed, as many as 90 percent of those who join a high intensity group ultimately decide to leave.<ref>Barker, 1983.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Most authors agree that some people experience problems after leaving a cult. These include negative reactions in the individual leaving the group as well as negative responses from the group such as [[shunning]]. There are disagreements regarding the frequency of such problems, however, and regarding the cause.

| + | Exit Counselor [[Carol Giambalvo]] believes most people leaving a cult have associated psychological problems, such as feelings of guilt or shame, depression, feeling of inadequacy, or fear, that are independent of their manner of leaving the cult.<ref>Carol Giambalvo, Post-cult problems.</ref> However, sociologists [[David Bromley]] and [[Jeffrey Hadden]] note a lack of empirical support for alleged consequences of having been a member of a cult or sect, and substantial empirical evidence against it. They cite the fact that a large proportion of people who get involved in NRMs leave within two years; the overwhelming proportion of those who leave do so of their own volition; and that 67 percent felt "wiser for the experience."<ref>Brombly and Hadden, 1993, 75-97.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | According to Barker (1989), the greatest worry about potential harm concerns the central and most dedicated followers of a [[new religious movement]] (NRM). Barker mentions that some former members may not take new initiatives for quite a long time after disaffiliation from the NRM. This generally does not concern the many superficial, short-lived, or peripheral supporters of a NRM. <!-- Membership in a cult usually does not last forever: 90% or more of cult members ultimately leave their group by death<ref>[[Eileen Barker|Barker, E.]] ''The Ones Who Got Away: People Who Attend Unification Church Workshops and Do Not Become Moonies''. In: Barker E, ed. ''Of Gods and Men: New Religious Movements in the West'''. Macon, Ga. : Mercer University Press; 1983. ISBN 0-86554-095-0</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Galanter M. ''[[Unification Church]] ('Moonie') dropouts: psychological readjustment after leaving a charismatic religious group'', ''American Journal of Psychiatry''. 1983;140(8):984-989.</ref>. —>

| + | ===Criticism by former members=== |

| | + | The role of former members in the controversy surrounding cults has also been widely studied by social scientists. Former members in some cases become public opponents against their former group. The former members' motivations, the roles they play in the anti-cult movement, and the validity of their testimonies are controversial. Scholars suspect that at least some of their narratives—especially concerning so-called "[[mind control]]"—are colored by a need of self-justification, seeking to reconstruct their own past, and to excuse their former affiliations, while blaming those who were formerly their closest associates. |

| | | | |

| − | Exit Counselor Carol Giambalvo believes most people leaving a cult have associated psychological problems, such as feelings of guilt or shame, depression, feeling of inadequacy, or fear, that are independent of their manner of leaving the cult. Feelings of guilt, shame, or anger are by her observation worst with castaways, but walkaways can also have similar problems. She says people who had interventions or a rehabilitation therapy do have similar problems but are usually better prepared to deal with them.<ref>Giambalvo, Carol, ''Post-cult problems'' [http://www.csj.org/infoserv_articles/giambalvo_carol_postcult_problems.htm]</ref>

| + | Moreover, although some cases of abuse are incontrovertible, hostile ex-members have been shown to shade the truth and blow out of proportion minor incidents, turning them into major abuses.<ref>Gordon Melton, [http://www.cesnur.org/testi/melton.htm Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory.] Retrieved July 22, 2008.</ref> Sociologist and legal scholar [[James Richardson (sociologist)|James T. Richardson]] contends that because there are a large number of NRMs, a tendency exists to make unjustified generalizations about them, based on a select sample of observations of life in such groups or the testimonies of (ex-)members.<ref>Richardson, 1989.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Sociologists Bromley and Hadden note a lack of empirical support for alleged consequences of having been a member of a cult or sect, and substantial empirical evidence against it. These include the fact that the overwhelming proportion of people who get involved in NRMs leave, most short of two years; the overwhelming proportion of people who leave of their own volition; and that two-thirds (67%) felt "wiser for the experience."<ref>Hadden, J and Bromley, D eds. (1993), ''The Handbook of Cults and Sects in America.'' Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc., pp. 75-97.</ref>

| + | ==Governments and "cults"== |

| | + | Some governments have taken restrictive measures against "cults" and "sects." In the 1970s, some U.S. judges issued "conservatorship" orders revoking the freedom of an NRM to remain in his or her group so as to facilitate a [[deprogramming]] attempt. These actions were later ruled unconstitutional be higher courts. Several attempts at state legislation to legalize deprogramming likewise failed as the "mind control" theory came to be discredited in courts. However, it has been argued that the "[[brainwashing]]" theory promulgated by the anti-cult movement contributed to U.S. actions leading to the deaths of close to 100 members of the [[Branch Davidian]] group in [[Waco, Texas|Waco]], [[Texas]].<ref>D. Anthony, T. Robbins, S. Barrie-Anthony, "Cult and Anticult Totalism: Reciprocal Escalation and Violence," ''Terrorism and Political Violence'' Spring 2002: 211-240.</ref> It has also been alleged that negative perceptions of a group by prosecutors was a factor in the [[income tax]] case against the Reverend [[Sun Myung Moon]] of the Unification Church, which resulted in his serving more than a year in prison in the mid 1980s.<ref>Sherwood, 1991.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Popular authors Conway and Siegelman conducted a survey and published it in the book ''Snapping'' regarding after-cult effects and deprogramming and concluded that people deprogrammed had fewer problems than people not deprogrammed. The [[BBC]] writes that in a survey done by Jill Mytton on 200 former cult members most of them reported problems adjusting to society and about a third would benefit from some counseling.<ref>BBC News 20 May 2000: Sect leavers have mental problems [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/755588.stm]</ref>

| + | More recently, governments in Europe have sought to control "sects" through various state actions. The annual report by the [[United States Commission on International Religious Freedom]] have criticized these initiatives as "…fueled an atmosphere of intolerance toward members of minority religions." The U.S. State Department has criticized France, Germany, Russia, and several other European states for repressive measures against "sects." In Japan, deprogramming cases still find their way into the civil courts, while police allegedly refuse to bring criminal charges against the perpetrators. Meanwhile the Chinese government has become notorious for its mistreatment of members of the [[Falun Gong]] spiritual movement and other groups denounced by the government as "heretical cults." |

| − | | |

| − | Burks (2002), in a study comparing Group Psychological Abuse Scale (GPA) and Neurological Impairment Scale (NIS) scores in 132 former members of cults and cultic relationships, found a positive correlation between intensity of thought reform environment as measured by the GPA and cognitive impairment as measured by the NIS. Additional findings were a reduced earning potential in view of the education level that corroborates earlier studies of cult critics (Martin 1993; Singer & Ofshe, 1990; West & Martin, 1994) and significant levels of depression and dissociation agreeing with Conway & Siegelman, (1982), Lewis & Bromley, (1987) and Martin, et al. (1992).<ref>Burks, Ronald, ''Cognitive Impairment in Thought Reform Environments'' [http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~rb267689/#_Toc2952976]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | According to Barret, in many cases the problems do not happen while in a movement, but when leaving, which can be difficult for some members and may include [[psychological trauma]]. Reasons for this trauma may include: [[conditioning]] by the religious movement; avoidance of uncertainties about life and its meaning; having had powerful religious experiences; love for the founder of the religion; emotional investment; fear of losing [[salvation]]; bonding with other members; anticipation of the realization that time, money, and efforts donated to the group were a waste; and the new freedom with its corresponding responsibilities, especially for people who lived in a community. Those reasons may prevent a member from leaving even if the member realizes that some things in the NRM are wrong. According to Kranenborg, in some religious groups, members have all their social contacts within the group, which makes disaffection and disaffiliation very traumatic.<ref>Kranenborg, Reender Dr. (Dutch language) ''Sekten... gevaarlijk of niet?/Cults... dangerous or not?'' published in the magazine ''Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland/Religious movements in the Netherlands'' nr. 31 ''Sekten II'' by the [[Vrije Universiteit|Free university Amsterdam]] (1996) ISSN 0169-7374 ISBN 90-5383-426-5</ref>

| |

| − | | |