Covenant

The concept of covenant is one that is deemed to be contractual in nature and has implications of legal trappings associated with the particular culture in which it is situated. There is an under current of Godly concern for humanity elicited in the idea of Covenant. It is underscored with the need for humans to develop and maintain faith in a God who pledges his word in covenants take these two aspects, concern and faith, as their core constituents.

Etymology

The term “covenant” is used in the Bible more than three hundred times and is well represented in both the Old and New Testaments. The Hebrew term usually translated as covenant is berith (berît) which is associated with concepts such as “agreement” and “arrangement”, however its etymological origins are more closely associated with partaking of a meal (symbolically or actually) as well as with the concept of ‘cutting’, as in 'to cut’ a covenant. The Greek application of this term derives from diath‘k‘ (*4"2Z60) which is often paraphrased as ‘last will’ or even as ‘testament’.

Concepts of Covenant in Antiquity

While covenant often implies a Biblical connotation, there were certainly many forms of covenants and legal agreements within the cultures of extra-biblical groups and non-Hebrew races. The nations surrounding the Hebrews of the Old Testament routinely entered into suzerainty covenants between rulers and their subjects. This type of covenant has an implicit condition that one party is not equal in standing compared to the other. One party commands the formation of the covenant and the other party obeys its conditions. However, covenants between nations and tribes were common as well as between individuals and families. This type of agreement implies a certain equal standing between the parties and can be termed ‘parity covenants’. In such cases conditions were either negotiated or offered and accepted.

The common perception of the term covenant implies a contract or binding agreement, with at least two parties, revolving around a promise or a set of promises that each party holds out in relation to the other. Additionally, covenantal terms have other limits or conditions attached: there may be property rights or access; a time limit (a perpetual covenant for instance); a curse or penalty for breaking the covenant; a responsibility or duty imposed; renewal options; intermarriage requirements; or any other conditions suitable to the covenanting parties.

Quite often there was a binding of the covenant that required a ritual meal, especially the use of salt or even the use of blood in some form to seal the covenant. In extreme instances the parties might actually taste each other’s blood (becoming brothers in blood), but more commonly sacrificial animals were cut into halves and the testamentary participants stood between them while they ratified their agreement. These covenants were often concluded in the presence of witnesses. Symbols were often created to mark a covenant and to commemorate it at later dates.

With respect to Biblical covenants, many of the features pre-existing in covenantal concepts are found to be incorporated within them. However, since one of the covenanting parties in the Biblical covenants is a supernatural being, biblical covenants take on an implicitly greater significance than that of a covenant between mere mortal humans. When God is partner, or signatory, the conditions and terms take on a grander scale and even tend to perpetuity and all of humanity in their scope. The significance of Biblical covenants has given rise to its own branch of theology: Covenantal Theology. Much research and debate surround this issue and covenants underpin many theological implications for most denominations as well as three of the great religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Number of Biblical Covenants

With respect to Biblical covenants, there are disagreements among theologians as to the exact number of covenants there are. As mentioned above, some covenants are between individuals and these might be best viewed as ‘minor’ covenants with those between God and humans as ‘major’ covenants. The list of major covenants is also subject to debate and numbers from five to eight or more. It is said that some covenants have been renewed and reestablished for various reasons. Another view is that the covenants of the Old Testament point to the figure of Jesus Christ in the New Testament and therefore there are only two covenants with that of the New Testament being the only one of lasting significance and implication for modern times.

The biblical covenants deemed to be of greatest significance follow in order of their invocation.

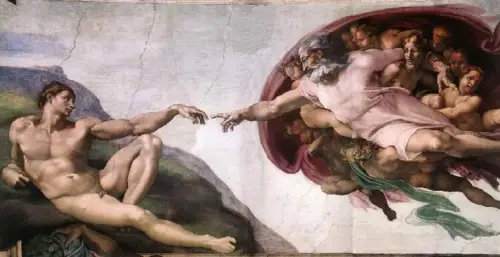

1) The Edenic Covenant, Genesis 1:26-30:

The first covenant is found in the Book of Genesis and is invoked by God upon his human creations. This covenant is found at the end of the first creation account, and it is a clear indication of the concern God has for what he creates. Humankind is special for it was created “in his image” and God bears responsibility for what he has created. Humans are explicitly given dominion over the creation and implicitly are held responsible for its well-being because “God looked at everything he had made, and had found it very good” (Gen, 1:31). To insure the ability of humans to undertake and accomplish such a responsibility, God then instituted the seventh day as a day of rest and regeneration.

God's concern for humankind stems from God’s desire for a relationship. Being made in God’s image implies there is some similarity through which communication can be made. The ongoing God-human relationship will be sustained by a growing faith in God and his promises by future generations. While this covenant seems to lack parity between the parties, God’s desire to create and commune with his creatures softens the ruler/subject distinction found in the earlier non-biblical covenants. God is generous and powerful and can sustain those he has appointed to have dominion over the lessor objects of his creation.

2) The Noachian Covenant, Genesis 9:8-17:

These verses now contain the translated word ‘covenant’ five times. This is a significant covenant in a number of ways. As in the usual covenant typology, blood has been invoked in this covenant. In fact the blood comes from the slaying of all of humankind because the God-human relationship had been broken through human disobedience which entered the world shortly after the invocation of the Edenic Covenant. Once again, the fundamental ingredient of faith is paramount in this covenant along with God’s concern for humankind’s existence. If humankind cannot be sustained in circumstances of disobedience and evil, it must be sustained when faith is present, especially when obedience comes from such faith. This man, Noah, and his family, have maintained obedience to God’s will for humankind and in faithful obedience Noah followed God’s commands to the letter. He built the life-sustaining ark and he gathered the animals as instructed. Those who mocked Noah and were barred from the covenant perished while humanity itself survived through the faith of these individuals. Once the blood sacrifice was provided, God entered into a perpetual covenant with Noah and those who followed him. God promised “that never again shall all bodily creatures be destroyed by the waters of a flood; there shall not be another flood to devastate the earth” (v. 11). Another covenantal constituent, the symbol, is evident here for God “set [his] bow in the clouds to serve as a sign of the covenant between [him] and the earth” (v. 14) The covenant is not only perpetual, but it extends to all of creation, thus a supernatural element is joined with a supranatural component in the metaphysical covenant of God, creation, and humanity. The symbol of the rainbow joins God and humans in a reminder of the price for disobedience and the faith that ensures forgiveness. There is an additional component of this covenantal story that plays into the words of Irenaeus. The ark, as the first saviour of all of humankind is a foreshadowing of the coming of Jesus Christ as the final saviour in the last times.

3) The Abrahamic Covenant, Genesis 12:2-3, 15, 17:1-14, 22:15-18:

Continuing in the Book of Genesis are a number of covenants made by God to Abraham and, by extension, to all of humanity. The first involves God’s introduction of himself to Abram, who did not know God prior to this incident. Abram was a prosperous herdsman without progeny and he despaired of having offspring because of his and his wife’s great age. But God had plans to use Abram as a means of populating the earth with those with whom he would continue the God-human relationship. But the plan hinged on the acceptance of Abram to leave his familiar territory and strike out into the unknown at the request of God. In return, the faith shown by Abram would be rewarded with great blessings: Abram will be made into a great nation, his very name will be great and a blessing, and this blessing will extend to all the communities of the earth. Once again, there is a covenant mediated by God to a faithful individual, but extended beyond his time and place to all of humankind who choose to continue the relationship.

The next Abrahamic Covenant is recorded in Chapter 15. This covenant is a reaffirmation of the promise of progeny and it is ‘cut’ in the manner of the ancient covenants. Here we see the sacrificial animals are cut into two parts and the Lord’s presence passes between them in the form of “a smoking brazier and a flaming torch” (v. 17). The completion of this covenant is almost thwarted by the presence of birds of prey (representing the evil one) who swoop down on the carcasses, but were prevented from doing so by Abram. Clearly Abram’s faith assisted him in warding off the effects of evil. This covenant confirms the numerous descendants promised earlier and it also forewarns the Egyptian captivity and eventual release documented in the Book of Exodus. The future territories to be awarded to God’s chosen people, Abram’s descendants, are detailed in this covenant. Thus, the descendants will identify with their promised land. This theme will surface in later covenants.

The third Abrahamic Covenant is also known as “The Covenant of Circumcision.” It is detailed in Chapter 17 and takes place when Abram is ninety-nine years old. God encourages the God-human relationship by asking Abram to “walk in my presence and be blameless” (v. 1). Once again, the theme of relation and righteousness before God becomes a covenantal component. God has observed Abram’s faith and right conduct and builds upon his earlier promises of progeny by extending the promise to include “a host of nations” (v. 5) that will issue from Abram. This covenant is also associated with land and a symbol. The land is the entire land of Canaan and the symbol is the act of circumcision. Here we see that conditions are being imposed by God on the party and future parties of the covenant. God will be their God. That is, they must have no other gods in their lives. To prevent such a thing from happening through intermarriage, Abram and his male descendants will show they have only one God by being circumcised. Any potential heathen marriages will be stymied by this sign in the flesh of the Israelites for all generations. There is an ongoing element of ‘cut’ and blood in this covenant that remains consistent with the properties found in earlier covenants. Significant with this covenant is the name change of Abram to Abraham. He is immediately obedient and ratifies the covenant by circumcising his whole male household.

The fourth Abrahamic Covenant is found in Chapter 22 and involves faith and obedience. It is also another ratification of the earlier promises of descendants and nations. Prior to this covenant, Abraham has a son, Isaac, from his wife, Sarah, and the earlier covenantal promises seem to be on the way to fulfillment. However, as a test of his faith, Abraham is commanded to sacrifice his only son. Not only is this disheartening from the paternal point of view, but it severely strains his faith in the promise of progeny that will become as numerous as the stars in the heavens.

But Abraham is obedient and makes the arrangements, traveling to a place suitable for the sacrifice and preparing his son for the ritual. As he is about to complete the act, his hand is stayed by a voice from the Lord’s messenger. However, Abraham is supplied with a ram and the sacrifice is completed. The elements of this covenant also demonstrate faith, obedience, and God’s interest in an ongoing relationship. Once again the earlier promises of future nations are restated and Abraham is blessed by God. The act of Isaac, the only son, obediently carrying the wood of the holocaust on his back is a foreshadowing of Jesus Christ carrying the means of his execution on the way to Calvary. God will maintain the God-human relationship down the centuries even at the expense of sacrificing his only son.

4) The Mosaic (Sinaitic) Covenant, Exodus 19: 5-6: This famous covenant is actually an extension of the Abrahamic covenants and is addressed to those people whom God, acting through Moses, delivered out of bondage in the land of Egypt. Its location is the Israelite camp at the foot of Mount Sinai and Moses received it on behalf of the people. In restating the Abrahamic covenant, God tells Moses to tell the people “if you hearken to my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my special possession, dearer to me than all other people, though all the earth is mine. You shall be to me a kingdom of priests, a holy nation” (v. 5-6). At verse 8 is given the response of the people, “Everything the Lord has said, we will do.” Thus there is an understanding here of a special, of a covenantal relationship between the Israelites of the captivity and God. There is a further understanding of the sovereignty of God over all the earth and over all people, with a special concern for those who had suffered persecution because they were Israelites in a foreign land. The Book of Exodus makes a number of references to the suffering in the captivity and to God’s awareness of and response to their pleas. The core of this covenant are the later conditions as laid out in the Ten Commandments (see Ch 20: 1-17). God, as supreme authority in the lives of the Israelites, sets out a code of conduct and right attitudes that will guide the relations of these people within the community and with God. This covenant, after reception of further legal and sacrificial prescriptions, was ratified in blood by Moses: Then having sent certain young men of the Israelites to offer holocausts and sacrifice young bulls as peace offerings to the Lord, Moses took half the blood and put it in large bowls; the other half he splashed on the altar. Taking the book of the covenant he read it aloud to the people, who answered, “All that the Lord has said, we will heed and do.” Then he took the blood and sprinkled it on the people [blood brothers], saying, “This is the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you in accordance with all the words of his” (Ex. 24: 5-8).

5) The Palestinian Covenants, (The Covenant of the Repentant) Deuteronomy 30: 1-10 & (The New Covenant) Jeremiah 31:31-34:

These two covenants have some similarity in that they reaffirm the possession of the land of Palestine by the Israelites. The first is instituted after the giving of the final words of Moses to the people he led out of captivity. Their story is repeated and their legal obligations, along with penalties for violation, are enumerated by Moses. They have received the Law, but they will not always keep it, even though they are about to take possession of their promised land. Moses is prophesying their future periods of disobedience and their dispersals from the land that these will entail. They will be conquered and taken captive again for their occasions of disobedience. But there is an underlying theme of God’s forgiveness and desire to restore the God-human relationship with them. God’s pity will be activated when, in their hearts, they remember what was said and repent, relying once again on God’s guidance in their lives. No matter how far they are scattered they will return to possess this land once again. Continuing the theme of blood and ‘cut’, in convenantal terminology, “The Lord your God, will circumcise your hearts and the hearts of your descendants, that you may love the Lord, your God, with all your heart and all your soul, and so may live” (v. 6). These words are reminiscent of the giving of the Ten Commandments of the previous covenant and they point to the establishment of an unending kingdom that is enumerated in the Davidic Covenant. Following this promise is the promise of bounty to be given from the fruits of their labors and the promise of offspring of the people and their animals as well as abundant crops. The land and the people will bear fruit as a sign of God’s pleasure when they are obedient. The second covenant follows a period of dispersal when the people are returning once again to occupy the land of their inheritance. It again refers to the imagery of the heart. However, this New Covenant unites both the houses of Judah and Israel under a new formula. The former covenant was one of the Law. The Law could not always be fulfilled and required a penalty which was mediated through the priesthood. This new covenant’s laws will be interior, there will be a conversion of attitude that results in loving the Lord instead of fearing him. They will want to follow his guidelines out of recognition for his generosity and concern and not in fear of his retribution for failure. In fact, their transgression of the Law will no longer even be remembered. Additionally, knowledge of God will be extended to all nations. This covenant has implications for the future coming of Jesus Christ as both the “New Covenant” and as the exemplar of the priestly office.

6) The Davidic Covenant, 2 Samuel 7:9-16:

Here is a personal covenant that God generously makes to David, the second king of the Israelites. By extension its promises are extended to David’s subjects, God’s chosen people. This covenant has great implications for the various prophecies that point to Jesus as the future messiah. It is stimulated by David’s appreciation of God’s beneficence toward him and he notes the ark of God has only a tent while he is enthroned in palatial splendor. God begins this covenant by reminding David that God has been with him and he promises to make David’s name great. The covenant is then extended to the Israelites with a promise that they will dwell in their new lands without interference from their neighbors. David will no longer have to defend the people from attacks. The covenant then establishes the perpetual throne and lineage of David’s kingdom through his heirs. Again, this becomes prophetic for the future coming of Jesus. God also foretells the greatness of Solomon who will build the temple and perpetuate David’s name. The relationship between this family and God is established and will endure even through their future failings with God’s laws. Thus, the Kingdom of David will endure forever. This covenant reinforces the idea that covenants are not simply legal contracts, they are a state of being between the people and God.

7) The Covenant of Christ (The New Covenant), 2 Corinthians 3:7-18, Galations 4:24-31, Hebrews 9, Matthew 26:27-28:

There is a strong argument found in various texts in the New Testament to indicate that the Old Testament covenants point to Jesus and are fulfilled in him. These arguments also diverge into disagreements about the role of the Israelites and others who have not known Christ or those who do not acknowledge his role as savior of humanity. Other arguments center on the role of the church in the fulfillment of the covenants or whether the Old Testament covenants have been fulfilled at all. There are distinctions between conditional and unconditional covenants with speculation about their current validity since biblical history shows the nation of Israel was unable to consistently abide by them. Finally, there are questions about whether there will be future fulfillment of any covenants deemed unfulfilled. This final covenant also raises questions about how the covenants are to be viewed. Matthew 26: 27-28 finds Jesus instituting the sacrament of the Eucharist the night before his arrest, trial, and death. He clearly proclaims the completion of his earthly mission when, taking the cup of wine, he tells his disciples, “Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the [new] covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins.” Once again we see the covenantal linkage with the spilling of blood. We also see here that this will be the final blood that will be necessary to be spilled to establish and maintain the God-human relationship. And we see that there will no longer be any need for a Levitical priesthood to intercede in the sacrificial atonement for sin. This is the establishment of a final covenant not based on law, but on forgiveness and remission of sin. This sacrifice of Jesus on the cross will transform him into the exemplar of the priesthood and the final mediator between God and humans. The question of covenantal status is addressed in many of the books of the New Testament. 2 Corinthians 3: 7-18 contrasts the Old and New Covenants. The veiled face of Moses is a passing condition but it is taken away by Christ. A veil remains over the hearts of those who hear the Book of Moses but it is removed when they turn toward the person of Jesus. In Jesus there is the (Holy) Spirit and this is a Spirit of freedom which transforms the faithful into the “same image [of Christ] from glory to glory” (v. 18). Here is the view that the Old Covenants have passed away in their importance and, more important, in their approach to God. The Old Covenants were legalistic and underpinned by adherence to the Law, but the New Covenant is a covenant of faith based on love as espoused by Jesus Christ and fulfill the earlier “New Covenant” written in Jeremiah 31:31. This theme of greater freedom under the New Covenant is brought out in Galations 4:24-31. This is a comparison between those under the law, represented by Ishmael the son of the slave Hagar, and Abraham’s son Isaac, born of Sarah who was a free woman. This allegory ends at verse 31 which says, “Therefore, brothers, we are children not of the slave woman but of the freeborn woman,” thus maintaining the Old Covenants were restricting while the New Covenant is freeing. Finally, the entire Book of Hebrews is filled with explanations of the priesthood of Jesus and his work of salvation. It also contains covenantal references which bear on the question of the supremacy of the covenants and their fulfilment. Chapter 9 is especially helpful for it notes the layout of the tabernacle which the Mosaic Covenant required for the atonement of violations of the Law. The priests were regularly required to enter it to perform the requisite sacrifices. But the high priest had to go inside the inner tabernacle annually to atone for his own sins and those of the people. In other words the priests needed to be reconciled with God in order to perform their duties. However, Christ, as the ultimate high priest, has performed for all time the redemption for sin through the shedding of his own blood. His blood has done more than the blood of all the sacrifices prior to his coming. “But now once for all he has appeared at the end of the ages to take away sin by his sacrifice” (v. 26). These, and other scriptural references, arguably point to Jesus Christ as the final covenant of the God-human relationship.

References:

- Cairns, A. Dictionary of Theological Terms. Ambassador Emerald International. Belfast, Northern Ireland. Expanded Edition, 2002.

- Hastings, J. ed. Hastings’ Dictionary of the Bible. Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. U.S.A., 2005.

- Myers, A.C. ed. The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, MI.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company,1987.

- The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI.: Zondervan. 1975.

- Kittel G. ed. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI.: Eerdmans Printing Company,1964.

- New American Bible. St. Joseph Edition. New York, NY.: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1991.