Difference between revisions of "Court" - New World Encyclopedia

Cheryl Lau (talk | contribs) |

Cheryl Lau (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

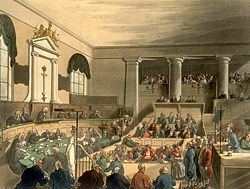

[[Image:Old Bailey Microcosm edited.jpg|250px|thumb|A trial at the [[Old Bailey]] in [[London]] as drawn by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin for Ackermann's Microcosm of London (1808-11).]] | [[Image:Old Bailey Microcosm edited.jpg|250px|thumb|A trial at the [[Old Bailey]] in [[London]] as drawn by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin for Ackermann's Microcosm of London (1808-11).]] | ||

| − | A '''court''' is a public forum used by a power base to [[adjudication|adjudicate]] disputes and dispense [[private law|civil]], | + | A '''court''' is a public forum used by a power base to [[adjudication|adjudicate]] disputes and dispense [[private law|civil]], labor, administrative and [[criminal justice|criminal]] [[justice]] under its [[law]]s. In [[common law]] and [[civil law (legal system)|civil law]] [[state (law)|states]], courts are the central means for [[dispute resolution]], and it is generally understood that all persons have an ability to bring their claims before a court. Similarly, those accused of a crime have the right to present their defense before a court. As a forum where justice is judicially administered, a court replaces the earlier justice which was meted out by the head of a family clan or sovereign wherein peace had its foundation in the family or royal authority. |

Court facilities range from a simple farmhouse for a village court in a rural community to huge buildings housing dozens of courtrooms in large cities. | Court facilities range from a simple farmhouse for a village court in a rural community to huge buildings housing dozens of courtrooms in large cities. | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

In a common law system, appellate courts may be arranged in a hierarchy and their function is to review the decisions of trial courts (and of lower appellate courts) and, generally, they only address questions of law, i.e. whether the lower courts interpreted and applied the law correctly, or procedure. These hearings do not usually involve considering factual matters unless new [[evidence (law)|evidence]] has come to light. Such factual evidence as is admitted will only be considered for the purposes of deciding whether the case should be remitted to a first instance court for a retrial unless, in criminal proceedings, it is so clear that there has been a [[miscarriage of justice]] that the [[conviction (law)|conviction]] can be [[quash]]ed. | In a common law system, appellate courts may be arranged in a hierarchy and their function is to review the decisions of trial courts (and of lower appellate courts) and, generally, they only address questions of law, i.e. whether the lower courts interpreted and applied the law correctly, or procedure. These hearings do not usually involve considering factual matters unless new [[evidence (law)|evidence]] has come to light. Such factual evidence as is admitted will only be considered for the purposes of deciding whether the case should be remitted to a first instance court for a retrial unless, in criminal proceedings, it is so clear that there has been a [[miscarriage of justice]] that the [[conviction (law)|conviction]] can be [[quash]]ed. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Supreme courts== |

| + | In some countries, provinces and states, the '''supreme court''' functions as a '''court of last resort''' whose rulings cannot be challenged. However, in some [[jurisdiction]]s other phrases are used to describe the highest courts. There are also some jurisdictions where the supreme court is not the highest court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although some countries and subordinate states follow the [[Law of the United States|American]] model of having a supreme court that interprets that jurisdiction's [[constitution]], others follow the [[Austria]]n model of a separate [[constitutional court]] (first developed in the [[History of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)#Politics of the new state|Czechoslovak constitution]] and [[Austrian Constitution]] of [[1920]]). The constitutionality of a law is implicit and cannot be challenged. Furthermore, in e.g. [[Finland]], [[Sweden]], [[Czech republic]] and [[Law of Poland|Poland]], there is a separate [[Supreme Administrative Court]] whose decisions are final and whose jurisdiction does not overlap with the Supreme Court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many higher courts create through their decisions [[case law]] applicable within their respective jurisdictions or interpret [[civil code|codal]] provisions in [[civil law (legal system)|civil law]] countries to maintain a uniform interpretation: | ||

| + | *Most [[common law]] nations have the doctrine of ''[[stare decisis]]'' in which the previous [[ruling]]s ([[decision]]s) of a court constitute binding [[precedent]] upon the same court or courts of lower status within their jurisdiction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Constitutional court== | ||

| + | [[Image:Konstsud.jpg|thumb|275px|Constitutional court of Russia (architect [[Marian Peretiatkovich]], 1912).]] | ||

| + | A '''constitutional court''' is a [[high court]] that deals primarily with [[constitutional law]]. Its main authority is to rule on whether or not laws that are challenged are in fact [[unconstitutional]], i.e. whether or not they conflict with constitutionally established rights and freedoms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the other hand, there are countries who do not have separate constitutional courts, but instead delegate constitutional judicial authority to their [[supreme court]]. Nonetheless, such courts are sometimes also called "constitutional courts"; for example, some have called the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] "the world's oldest constitutional court" because it was the first court in the world to invalidate a law as unconstitutional (''[[Marbury v. Madison]]''), even though it is not a separate constitutional court. [[Austria]] established the world's first separate constitutional court in 1920 (though it was suspended, along with the constitution that created it, from 1934 to 1945); before that, only the U.S. and [[Australia]] had adopted the concept of [[judicial review]] through their supreme courts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Prerequisite for court adjudication== | ||

In the United States, a court must have [[personal jurisdiction]] over a defendant to hear a case brought by a [[plaintiff]] against that [[defendant]]. There are three kinds of personal jurisdiction: [[In personam|''in personam'' jurisdiction]], [[Jurisdiction in rem|''in rem'' jurisdiction]], and [[Quasi in rem|''quasi in rem'' jurisdiction]]. A detailed discussion of personal jurisdiction is beyond the scope of this article; however, personal jurisdiction (in the United States) generally refers to the legal sufficiency of the connection between the defendant and the forum (the [[U.S. state]]) in which the court is located. ''See e.g. [[Pennoyer v. Neff]]'', ''see also [[Minimum contacts]] and [[International Shoe v. Washington]]''. | In the United States, a court must have [[personal jurisdiction]] over a defendant to hear a case brought by a [[plaintiff]] against that [[defendant]]. There are three kinds of personal jurisdiction: [[In personam|''in personam'' jurisdiction]], [[Jurisdiction in rem|''in rem'' jurisdiction]], and [[Quasi in rem|''quasi in rem'' jurisdiction]]. A detailed discussion of personal jurisdiction is beyond the scope of this article; however, personal jurisdiction (in the United States) generally refers to the legal sufficiency of the connection between the defendant and the forum (the [[U.S. state]]) in which the court is located. ''See e.g. [[Pennoyer v. Neff]]'', ''see also [[Minimum contacts]] and [[International Shoe v. Washington]]''. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 37: | ||

courts operate: [[civil procedure]] for private disputes (for example); and [[criminal procedure]] for violation of the [[criminal law]]. | courts operate: [[civil procedure]] for private disputes (for example); and [[criminal procedure]] for violation of the [[criminal law]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Court penalties== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''Sanctions''' is the plural of '''sanction'''. Depending on context, a sanction can be either a punishment or a permission. The word is a [[contronym]]. | '''Sanctions''' is the plural of '''sanction'''. Depending on context, a sanction can be either a punishment or a permission. The word is a [[contronym]]. | ||

In a legal context, [[sanctions (law)|sanctions]] are penalties imposed by the courts. | In a legal context, [[sanctions (law)|sanctions]] are penalties imposed by the courts. | ||

| − | |||

| + | ===Sanctions involving countries=== | ||

* [[International sanctions]], punitive measures adopted by a country or group of countries against another nation for political reasons | * [[International sanctions]], punitive measures adopted by a country or group of countries against another nation for political reasons | ||

** [[Diplomatic sanctions]], the reduction or removal of diplomatic ties, such as embassies | ** [[Diplomatic sanctions]], the reduction or removal of diplomatic ties, such as embassies | ||

| Line 54: | Line 64: | ||

To date, the Court has opened investigations into four situations: Northern [[Uganda]], the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]], the [[Central African Republic]] and [[Darfur]].<ref name=cases/> The Court has issued eight arrest warrants<ref name=economist>{{cite web |url= http://www.economist.com/world/international/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9441341|title= How the mighty are falling|accessdate= 2007-07-17|date= 2007-07-05|publisher= ''The Economist''}}</ref> and one suspect, [[Thomas Lubanga]], is in custody, awaiting trial.<ref name=2006report/> | To date, the Court has opened investigations into four situations: Northern [[Uganda]], the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]], the [[Central African Republic]] and [[Darfur]].<ref name=cases/> The Court has issued eight arrest warrants<ref name=economist>{{cite web |url= http://www.economist.com/world/international/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9441341|title= How the mighty are falling|accessdate= 2007-07-17|date= 2007-07-05|publisher= ''The Economist''}}</ref> and one suspect, [[Thomas Lubanga]], is in custody, awaiting trial.<ref name=2006report/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Juvenile court== |

| − | + | '''Juvenile courts''' or '''young offender courts''' are courts specifically created and given authority to [[Trial (law)|try]] and pass judgments for [[crime]]s committed by persons who have not attained the [[age of majority]]. In most modern [[legal system]]s, crimes committed by children and minors are treated differently and differentially (unless severe, like murder or gang-related offenses) regarding the same crimes committed by [[adult]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | One of the purposes Juvenile court was founded on was to give young, impressionable youth a second chance supposedly offering counseling and other programs for rehabilitation, as plain punishment was deemed less beneficial. |

| − | + | Generally, only those between the ages of seven and thirteen years old are accountable in a juvenile court.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://criminal.findlaw.com/crimes/juvenile-justice/when-minor-commits-crime.html|title=When a Minor Commits A Crime|publisher=Find Law |accessdate=2007-05-31}}</ref> Someone below age seven is considered too young and those above age fourteen are considered old enough to be held accountable in either juvenile or adult courts. However, not all juveniles who commit a crime may end up in juvenile court. A police officer has three choices: | |

| − | + | # Detain and warn the minor against further violations, and then let the minor go free | |

| − | + | # Detain and warn the minor against further violations, but hold the minor until a parent or guardian comes for the minor | |

| − | + | # Place the minor in custody and refer the case to a juvenile court. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Ecclesiastical court== |

| − | + | An '''ecclesiastical court''' (also called "Court Christian" or "Court Spiritual") is any of certain [[court]]s having [[jurisdiction]] mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the [[Middle Ages]] in many areas of [[Europe]] these courts had much wider powers than before the development of [[nation state]]s. They were experts in interpreting [[Canon law]], a basis of which was the [[Corpus Juris Civilis]] of [[Justinian I|Justinian]] which is considered the source of the [[Civil law (legal system)|civil law]] legal tradition. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 22:57, 25 September 2007

A court is a public forum used by a power base to adjudicate disputes and dispense civil, labor, administrative and criminal justice under its laws. In common law and civil law states, courts are the central means for dispute resolution, and it is generally understood that all persons have an ability to bring their claims before a court. Similarly, those accused of a crime have the right to present their defense before a court. As a forum where justice is judicially administered, a court replaces the earlier justice which was meted out by the head of a family clan or sovereign wherein peace had its foundation in the family or royal authority.

Court facilities range from a simple farmhouse for a village court in a rural community to huge buildings housing dozens of courtrooms in large cities.

Trial and appellate courts

Each state establishes a court system for the territory under its control. This system allocates work to courts or authorized individuals by granting both civil and criminal jurisdiction (in the United States, this is termed subject-matter jurisdiction). The grant of power to each category of court or individual may stem from a provision of a written constitution or from an enabling statute. In English law, jurisdiction may be inherent, deriving from the common law origin of the particular court. For this purpose, courts may be classified as trial courts (sometimes termed "courts of first instance") and appellate courts. Some trial courts may function with a judge and a jury: juries make findings of fact under the direction of the judge who makes findings of law and, in combination, this represents the judgment of the court. In other trial courts, decisions of both fact and law are made by the judge or judges. Juries are less common in court systems outside the Anglo-American common law tradition.

In a common law system, appellate courts may be arranged in a hierarchy and their function is to review the decisions of trial courts (and of lower appellate courts) and, generally, they only address questions of law, i.e. whether the lower courts interpreted and applied the law correctly, or procedure. These hearings do not usually involve considering factual matters unless new evidence has come to light. Such factual evidence as is admitted will only be considered for the purposes of deciding whether the case should be remitted to a first instance court for a retrial unless, in criminal proceedings, it is so clear that there has been a miscarriage of justice that the conviction can be quashed.

Supreme courts

In some countries, provinces and states, the supreme court functions as a court of last resort whose rulings cannot be challenged. However, in some jurisdictions other phrases are used to describe the highest courts. There are also some jurisdictions where the supreme court is not the highest court.

Although some countries and subordinate states follow the American model of having a supreme court that interprets that jurisdiction's constitution, others follow the Austrian model of a separate constitutional court (first developed in the Czechoslovak constitution and Austrian Constitution of 1920). The constitutionality of a law is implicit and cannot be challenged. Furthermore, in e.g. Finland, Sweden, Czech republic and Poland, there is a separate Supreme Administrative Court whose decisions are final and whose jurisdiction does not overlap with the Supreme Court.

Many higher courts create through their decisions case law applicable within their respective jurisdictions or interpret codal provisions in civil law countries to maintain a uniform interpretation:

- Most common law nations have the doctrine of stare decisis in which the previous rulings (decisions) of a court constitute binding precedent upon the same court or courts of lower status within their jurisdiction.

Constitutional court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether or not laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether or not they conflict with constitutionally established rights and freedoms.

On the other hand, there are countries who do not have separate constitutional courts, but instead delegate constitutional judicial authority to their supreme court. Nonetheless, such courts are sometimes also called "constitutional courts"; for example, some have called the Supreme Court of the United States "the world's oldest constitutional court" because it was the first court in the world to invalidate a law as unconstitutional (Marbury v. Madison), even though it is not a separate constitutional court. Austria established the world's first separate constitutional court in 1920 (though it was suspended, along with the constitution that created it, from 1934 to 1945); before that, only the U.S. and Australia had adopted the concept of judicial review through their supreme courts.

Prerequisite for court adjudication

In the United States, a court must have personal jurisdiction over a defendant to hear a case brought by a plaintiff against that defendant. There are three kinds of personal jurisdiction: in personam jurisdiction, in rem jurisdiction, and quasi in rem jurisdiction. A detailed discussion of personal jurisdiction is beyond the scope of this article; however, personal jurisdiction (in the United States) generally refers to the legal sufficiency of the connection between the defendant and the forum (the U.S. state) in which the court is located. See e.g. Pennoyer v. Neff, see also Minimum contacts and International Shoe v. Washington.

Civil law courts and common law courts

The two major models for courts are the civil law courts and the common law courts. Civil law courts are based upon the judicial system in France, while the common law courts are based on the judicial system in Great Britain. In most civil law jurisdictions, courts function under an inquisitorial system. In the common law system, most courts follow the adversarial system. Procedural law governs the rules by which courts operate: civil procedure for private disputes (for example); and criminal procedure for violation of the criminal law.

Court penalties

Sanctions is the plural of sanction. Depending on context, a sanction can be either a punishment or a permission. The word is a contronym. In a legal context, sanctions are penalties imposed by the courts.

Sanctions involving countries

- International sanctions, punitive measures adopted by a country or group of countries against another nation for political reasons

- Diplomatic sanctions, the reduction or removal of diplomatic ties, such as embassies

- Economic sanctions, typically a ban on trade, possibly limited to certain sectors such as armaments, or with certain exceptions (such as food and medicine)

- Military sanctions, military intervention

- Trade sanctions, economic sanctions applied for non-political reasons, typically as part of a trade dispute, or for purely economic reasons, and typically involving tariffs or similar measures, rather than bans.

International judicial institution

International judicial institutions can be divided into courts, arbitral tribunals and quasi-judicial institutions. Courts are permanent bodies, with near the same composition for each case. Arbitral tribunals, by contrast, are constituted anew for each case. Both courts and arbitral tribunals can make binding decisions. Quasi-judicial institutions, by contrast, make rulings on cases, but these rulings are not in themselves legally binding; the main example is the individual complaints mechanisms available under the various UN human rights treaties.

Institutions can also be divided into global and regional institutions.

The listing below incorporates both currently existing institutions, defunct institutions that no longer exist, institutions which never came into existence due to non-ratification of their constitutive instruments, and institutions which do not yet exist, but for which constitutive instruments have been signed. It does not include mere proposed institutions for which no instrument was ever signed.

International criminal court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) was established in 2002 as a permanent tribunal to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression, although it cannot currently exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression.[1] The court came into being on July 1 2002 — the date its founding treaty, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, entered into force[2] — and it can only prosecute crimes committed on or after that date.[3]

As of August 2007, 104 states are members of the Court; Japan will become the 105th state party on 1 October 2007.[4] A further 41 countries have signed but not ratified the Rome Statute.[5] However, a number of states, including China, India and the United States, are critical of the Court and have not joined.

The Court can generally exercise jurisdiction only in cases where the accused is a national of a state party, the alleged crime took place on the territory of a state party, or a situation is referred to the Court by the United Nations Security Council.[6] The Court is designed to complement existing national judicial systems: it can exercise its jurisdiction only when national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute such crimes.[7][8] Primary responsibility to punish crimes is therefore left to individual states.

To date, the Court has opened investigations into four situations: Northern Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic and Darfur.[9] The Court has issued eight arrest warrants[10] and one suspect, Thomas Lubanga, is in custody, awaiting trial.[11]

Juvenile court

Juvenile courts or young offender courts are courts specifically created and given authority to try and pass judgments for crimes committed by persons who have not attained the age of majority. In most modern legal systems, crimes committed by children and minors are treated differently and differentially (unless severe, like murder or gang-related offenses) regarding the same crimes committed by adults.

One of the purposes Juvenile court was founded on was to give young, impressionable youth a second chance supposedly offering counseling and other programs for rehabilitation, as plain punishment was deemed less beneficial. Generally, only those between the ages of seven and thirteen years old are accountable in a juvenile court.[12] Someone below age seven is considered too young and those above age fourteen are considered old enough to be held accountable in either juvenile or adult courts. However, not all juveniles who commit a crime may end up in juvenile court. A police officer has three choices:

- Detain and warn the minor against further violations, and then let the minor go free

- Detain and warn the minor against further violations, but hold the minor until a parent or guardian comes for the minor

- Place the minor in custody and refer the case to a juvenile court.

Ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court (also called "Court Christian" or "Court Spiritual") is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages in many areas of Europe these courts had much wider powers than before the development of nation states. They were experts in interpreting Canon law, a basis of which was the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian which is considered the source of the civil law legal tradition.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abraham, Henry Julian, The judicial process: an introductory analysis of the courts of the United States, England and France, NY: Oxford University Press, 1975. OCLC 1165844

- Smith, Christopher E., Coufts and trials: a reference handbook, Santa Barbara, CA: ABE-CLIO, 2003. ISBN 1-576-07933-3

- Warner, Ralph F., Everybody's guide to small claims court, Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Co., 1980. ISBN 0-201-08304-3

External links

- US federal courts Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- Directory of State Court websites Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- Court TV (coverage of major US trials) Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- Directory of local courts in the US Retrieved September 3, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarticle5 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedai2002 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarticle11 - ↑ International Criminal Court. Accession of Japan to the Rome Statute. Accessed 2007-07-19.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameduntreaty - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarticles12&13 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarticle17 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarticle20 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedcases - ↑ How the mighty are falling. The Economist (2007-07-05). Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named2006report - ↑ When a Minor Commits A Crime. Find Law. Retrieved 2007-05-31.