Difference between revisions of "Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (imported from wiki) |

m ({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Contracted}} | |

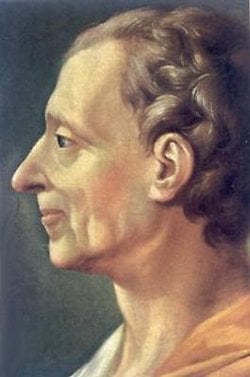

[[Image:Charles Montesquieu.jpg|right|framed|Portrait of Montesquieu in 1728.]] | [[Image:Charles Montesquieu.jpg|right|framed|Portrait of Montesquieu in 1728.]] | ||

{{French literature (small)}} | {{French literature (small)}} | ||

Revision as of 21:52, 27 September 2006

Template:French literature (small)

| Philosophy Portal |

- "Montesquieu" redirects here.

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (January 18, 1689 in Bordeaux – February 10, 1755), more commonly known as Montesquieu, was a French political thinker who lived during the Enlightenment. He is famous for his articulation of the theory of separation of powers, taken for granted in modern discussions of government and implemented in many constitutions all over the world. He was largely responsible for the popularization of the terms "feudalism" and "Byzantine Empire".

Biography

After having studied at the Catholic College of Juilly, he married Jeanne de Latrigue, a Calvinist who brought him a substantial dowry, when he was 26. The next year, he inherited a fortune upon the death of his uncle, as well as the title Baron de Montesquieu and Président à Mortier in the Parliament of Bordeaux. By that time, the United Kingdom had declared itself a constitutional monarchy after the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688, a radical reform by the standards of the time. And the long-reigning Sun King died in France, to be replaced by a series of mostly weak successors. These two events affected Montesquieu, who stressed them in his work. Soon afterwards he achieved literary success with the publication of his Lettres persanes (Persian Letters, 1721), a satire based on the imaginary correspondence of an Oriental visitor to Paris, pointing out the absurdities of contemporary society. After publishing this book, he started on another book, The Considerations on the Causes of the Grandeur and Decadence of the Romans [1734] which is considered a transition from The Persian Letters to his main work, De l'esprit des lois (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748), which was originally published anonymously and was enormously influential. In France, this book met with an unfriendly reception from both the supporters and the opponents of the regime. But, for the rest of Europe (and especially in England), it received the highest praise, albeit not without repercussions from the Catholic Church, which banned his book— along with many of his other works— in 1751 and included it on the Index.

Montesquieu is believed to have been a powerful influence on many of the American Founders, most notably James Madison, and English translations of his books remain in print to this day (Cambridge University Press edition: ISBN 0-521-36974-6).

Besides writing books and debating about politics, Montesquieu traveled for a number of years through Europe including Austria and Hungary, spending a year in Italy and then eighteen months in England before settling back in France. He was troubled by poor eyesight, and was completely blind by the time he died from a high fever in 1755. He was buried in L'église Saint-Sulpice in Paris, France.

Political views

Montesquieu's most radical work divided French society into three classes (or trias politica, a term he coined): the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the commons. Montesquieu saw two types of power existing: the sovereign and the administrative. The administrative powers were the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary. These should be divided up so that each power would have a power over the other. This was radical because it completely eliminated the three Estates structure of the French Monarchy: the clergy, the aristocracy, and third estate, from the estates, and erased any last vestige of a feudalistic structure. Likewise, there were three main forms of government. These were monarchies (governments run by a king or queen or emperor), which relied on the principle of honor; republics (governments run by elected leaders), which relied on the principle of virtue; and despotisms (governments run by dictators), which relied on fear. He believed that the best form of government was a monarchy, and he upheld the British constitution as ideal.

Like many of his generation, Montesquieu held a number of views that might today be judged controversial. While he endorsed the idea that a woman could run a government, he held that she could not be effective as the head of a family. He firmly accepted the role of a hereditary aristocracy and the value of primogeniture. His views have also been abused by modern revisionists; for instance, even though Montesquieu was ahead of his time as an ardent opponent of slavery, he has been quoted out of context in attempts to show he supported it.[citation needed]

One of his more exotic ideas, outlined in The Spirit of the Laws and hinted at in Persian Letters, is the climate theory, which holds that climate should substantially influence the nature of man and his society. He even goes so far as to assert that certain climates are superior to others, the temperate climate of France being the best of possible climates. His view is that people living in hot countries are "too hot-tempered," while those in northern countries are "icy" or "stiff." The climate in middle Europe thus breeds the best people. (This view is possibly influenced by similar statements in Germania by Tacitus, one of Montesquieu's favourite authors.)

It was Montesquieu's philosophy that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another" that prompted the creators of the Constitution to divide the U.S. government into three separate branches.

Further reading

- Pangle, Thomas, Montesquieu’s Philosophy of Liberalism (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1973, paperback reprint 1989), 336 pages.

- Reviews in European History (1974) and The Political Science Reviewer (1976), review essays in English.

- “Montesquieu” in Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800, ed. James Person, Jr. (Gale Publishing, 1988), vol. 7, pp. 350-52. Excerpts from chapter eight.

- Schaub, Diana J. Erotic Liberalism: Women and Revolution in Montesquieu's "Persian Letters". Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995.

List of works

- Les causes de l'écho (The Causes of an Echo)

- Les glandes rénales (The Renal Glands)

- La cause de la pesanteur des corps (The Cause of Gravity of Bodies)

- La damnation éternelle des païens (The Eternal Damnation of the Pagans, 1711)

- Système des Idées (System of Ideas, 1716)

- Lettres persanes (Persian Letters, 1721)

- Le Temple de Gnide (The Temple of Gnide, a novel; 1724)

- Arsace et Isménie ((The True History of) Arsace and Isménie, a novel; 1730)

- Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Considerations on the Causes of the Grandeur and Decadence of the Romans, 1734)

- De l'esprit des lois ((On) The Spirit of the Laws, 1748)

- La défense de «L'Esprit des lois» (In Defence of "The Spirit of the Laws", 1748)

- Pensées suivies de Spicilège (Thoughts after Spicilège)

See also

- Liberalism

- Contributions to liberal theory

- French Government

- Napoleon

External links

- Free full-text works online

- Montesquieu in The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Montesquieu in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Timeline of Montesquieu's Life

| Preceded by: Louis de Sacy |

Seat 2 Académie française 1728–1755 |

Succeeded by: Jean-Baptiste de Vivien de Châteaubrun bg:Шарл дьо Монтескьо ca:Montesquieu cs:Charles Louis Montesquieu da:Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu de:Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu es:Montesquieu eo:Charles Montesquieu fa:شارل دو مونتسکیو fr:Montesquieu gl:Charles de Montesquieu ko:샤를 루이 드 세콩다 몽테스키외 hr:Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu id:Montesquieu it:Montesquieu he:מונטסקייה hu:Montesquieu nl:Charles Montesquieu ja:シャルル・ド・モンテスキュー no:Charles Montesquieu nn:Charles Montesquieu pl:Monteskiusz pt:Charles de Montesquieu ro:Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu ru:Монтескьё, Шарль Луи simple:Montesquieu sk:Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu fi:Montesquieu sv:Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu tr:Montesquieu uk:Монтеск'є yi:מאָנטעסקיע zh:孟德斯鳩 CreditsNew World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here: The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia: Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed. |