Difference between revisions of "Charles Goodyear" - New World Encyclopedia

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) (→Death) |

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==Marriage and early career== | ==Marriage and early career== | ||

| − | In August of 1824 he was united in marriage with Clarissa Beecher, a woman of of remarkable strength of character and kindness of disposition; and one of great assistance to the impulsive inventor. Two years later the family moved to [[Philadelphia]], and there | + | In August of 1824 he was united in marriage with Clarissa Beecher, a woman of of remarkable strength of character and kindness of disposition; and one of great assistance to the impulsive inventor. Two years later the family moved to [[Philadelphia]], and there Goodyear opened a hardware store. His specialties were the new agricultural implements that his firm had been manufacturing, and after the first distrust of domestically-made goods had worn away — for a majority of agricultural implements were imported from [[England]] at that time — he found himself heading a successful business. |

| − | This continued to increase until it seemed that he was to be a wealthy man. But because Goodyear had extended credit too freely, | + | This continued to increase until it seemed that he was to be a wealthy man. But because Goodyear had extended credit too freely, losses from non-paying customers mounted. At the same time, he refused to declare bankruptcy for fear of relinquishing his rights to patent a number of inventions that he was in the process of perfecting. Under existing law, he was imprisoned time after time for failing to pay his debts. |

== Rubber research== | == Rubber research== | ||

Revision as of 16:58, 10 November 2007

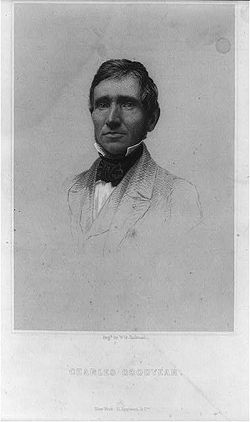

Charles Spencer Goodyear (December 29, 1800 - July 1, 1860) was the first American to vulcanize rubber, a process which he discovered in 1839 and patented on June 15, 1844. Although Goodyear is often credited with its invention, modern evidence has proven that the Mesoamericans used stabilized rubber for balls and other objects as early as 1600 B.C.E.[1]

Goodyear discovered the vulcanization process accidentally after five years of research. Joseph Holt later described Goodyear as having showed "almost superhuman perseverance" in his search for a more stable rubber[2]

Early life

Charles Goodyear was born in New Haven, Connecticut on December 29, 1800. He was the son of Amasa Goodyear and the oldest of six children. His father was quite proud of being a descendant of Stephen Goodyear, one of the founders of the colony of New Haven in 1638.

Amasa Goodyear owned a little farm on the neck of land in New Haven which is now known as Oyster Point, and it was here that Charles spent the earliest years of his life. When Charles was quite young, his father secured an interest in a patent for the manufacture of ivory buttons, and looking for a convenient location for a small mill, settled at Naugatuck, Connecticut, where he made use of the valuable water power that is there. Aside from his manufacturing, the elder Goodyear ran a farm, and between farming and manufacturing kept Charles Goodyear busy.

Goodyear is said to have considered a career in the ministry at an early age<<<Iles, George. 1912. Leading American inventors. New York: Henry Holt and Co. 177.>>>, but in 1816, he left his home and went to Philadelphia to learn the hardware business. He worked industriously until he was twenty-one years old, and then, returning to Connecticut, entered into partnership with his father in Naugatuck under the name Amasa Goodyear & Son. They manufactured a variety of agricultural implements, such as ivory and metal buttons, metal spoons and forks, scythes and clocks, along with a new line of farm tools and machinery designed by the elder Goodyear. <<<Iles 1912, 177>>>.

Marriage and early career

In August of 1824 he was united in marriage with Clarissa Beecher, a woman of of remarkable strength of character and kindness of disposition; and one of great assistance to the impulsive inventor. Two years later the family moved to Philadelphia, and there Goodyear opened a hardware store. His specialties were the new agricultural implements that his firm had been manufacturing, and after the first distrust of domestically-made goods had worn away — for a majority of agricultural implements were imported from England at that time — he found himself heading a successful business.

This continued to increase until it seemed that he was to be a wealthy man. But because Goodyear had extended credit too freely, losses from non-paying customers mounted. At the same time, he refused to declare bankruptcy for fear of relinquishing his rights to patent a number of inventions that he was in the process of perfecting. Under existing law, he was imprisoned time after time for failing to pay his debts.

Rubber research

Early business

Goodyear's first encounters with what was then called gum elastic but what we today call rubber was as a boy, but between the years 1831 and 1832, he began to carefully examine every article that appeared in the newspapers relative to this new material. Rubber's waterproofing qualities made it a good material to fashion such articles as boots and raincoats, but the material hardened in the cold, and softened in summer to an almost putty-like and sticky consistency. The Roxbury Rubber Company, of Boston, had been for some time experimenting with the gum, and believed it had found means for manufacturing goods from it. It had a large plant and was sending its goods all over the country. It was some of Roxbury's goods that first attracted Goodyear's attention. The company produced a line of life preservers, and Goodyear noticed that the valve used to inflate the preservers did not operate well. He created his own design, and reported back to the company with the improved product.

A company manager examined his design and was pleased with the Goodyear's ingenuity. But he confessed to Goodyear that the business was on the verge of ruin. Thousands of dollars worth of goods that they had determined to be of good quality were being returned, the gum having rotted, making them useless. Goodyear at once made up his mind to experiment on this gum and see if he could overcome the problems with these rubber products.

However, when he returned to Philadelphia, a creditor had him arrested and thrown into prison. While there, he tried his first experiments with India rubber. The gum was inexpensive then, and by heating it and working it in his hands, he managed to incorporate in it a certain amount of magnesia which produced a beautiful white compound and appeared to take away the stickiness.

He thought he had discovered the secret, and through the kindness of friends was enabled to improve his invention in New Haven. The first thing that he made was shoes, and he used his own house for a grinding, calendering and vulcanizing, with the help of his wife and children. His compound at this time consisted of India rubber, lampblack, and magnesia, the whole dissolved in turpentine and spread upon the flannel cloth which served as the lining for the shoes. It was not long, however, before he discovered that the gum, even treated this way, became sticky. His creditors, completely discouraged, decided that he would not be allowed to go further in his research.

Goodyear, however, had no mind to stop here in his experiments. Selling his furniture and placing his family in a quiet boarding place, he went to New York and in an attic, helped by a friendly druggist, continued his experiments. His next step was to compound the rubber with magnesia and then boil it in quicklime and water. This appeared to solve the problem. At once it was noticed abroad that he had treated India rubber to lose its stickiness, and he received international acclamation. He seemed on the high road to success, until one day he noticed that a drop of weak acid, falling on the cloth, neutralized the alkali and immediately caused the rubber to become soft again. This proved to him that his process was not a successful one. He therefore continued experimenting, and after preparing his mixtures in his attic in New York, would walk three miles to a mill in Greenwich Village to try various experiments.

In the line of these, he discovered that rubber dipped in nitric acid formed a surface cure, and he made many products with this acid cure which were held in high regard, and he even received a letter of commendation from Andrew Jackson.

Exposure to harsh chemicals, such as nitric acid and lead oxide, adversely affected his health, and once nearly suffocated by gas generated in his laboratory. Goodyear survived, but the resulting fever came close to taking his life.

Goodyear convinced a businessman, William Ballard,<<<ibid. 184.>>> to form a partnership based on his new process. The two established manufacturing facilities to produce clothing, life preservers, rubber shoes and a great variety of rubber goods, first at a factory on Bank Street in Manhattan, and then in Staten Island, where Goodyear also moved his family. Just about this time, when everything looked bright, the financial panic of 1837 swept away the entire fortune of his associate and left Goodyear penniless.

Goodyear's next move was to go to Boston, where he became acquainted with J. Haskins, of the Roxbury Rubber Company. Goodyear found him to be a good friend, who lent him money and stood by him when no one would have anything to do with the visionary inventor. A man named Mr. Chaffee was also exceedingly kind and ever ready to lend a listening ear to his plans, and to also assist him in a pecuniary way. About this time it occurred to Mr. Chaffee that much of the trouble that they had experienced in working India rubber might come from the solvent that was used. He therefore invented a huge machine for doing the mixing by mechanical means. The goods that were made in this way were beautiful to look at, and it appeared, as it had before, that all difficulties were overcome.

Goodyear discovered a new method for making rubber shoes and received a patent which he sold to the Providence Company in Rhode Island. However, a method had not yet been found to process rubber so that it would withstand hot and cold temperatures and acids, and so the rubber goods were constantly growing sticky, decomposing and being returned to the manufacturers.

The vulcanization process

In 1838, Goodyear met Nathaniel Hayward in Woburn, Massachusetts, where Hayward was running a factory. Some time after this Goodyear himself moved to Woburn, all the time continuing his experiments. Heyward had received in a dream a formula for hardening rubber by adding sulfur to gum, and exposing it to the heat of the sun. <<<Iles, 186.>>>Goodyear encouraged Hayward to patent his new discovery, which he did. Goodyear then purchased the patent from him. Using this process enabled Goodyear to produce better quality goods, but he also found that it did not penetrate deeply into the material. He thus became saddled with a large inventory of goods that were of no use to their purchasers.

In the winter of 1838, Goodyear noticed that some of the goods, when accidentally brought into contact with a hot stove, charred in the same way that leather would. He finally realized that some of the material was merely hardened, and not charred. It thus appeared that heating the rubber that had been treated with sulfur would harden it and remove its stickiness. This hardened rubber would not soften at elevated temperatures, nor become inflexible at low temperatures, the way untreated rubber would. He tried to bring this new discovery to the attention of friends and relatives, they could did not realize its significance. <<<ibid. 189, 190.>>> When summer came around, he found that objects fashioned with rubber made by his new process did not become soft.

Now Goodyear was sure that he had the key to the intricate puzzle that he had worked over for so many years. For a number of years he struggled and experimented and worked along in a small way, his family suffering with himself the pangs of extreme poverty. The winter of 1839-1840 was particularly severe, and Goodyear had to depend on friends for financing to support his family and continue his work. At the beginning of 1840 that a French firm made an offer for the use of his earlier process to produce rubber goods. Goodrich declined, saying that the new process that he was perfecting would be far superior to that which the French firm wanted to use.<<<Hubert, Philip Gengembre. 1893. Inventors. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 170.>>> At last he went to New York and showed some of his samples to William Ryder, who, with his brother Emory, at once appreciated the value of the discovery and started in to manufacturing. Even here, Goodyear's bad luck seemed to follow him, for the Ryder Bros. had failed and it was impossible to continue the business.

By 1841, he had, however, started a small factory at Springfield, Massachusetts, and his brother-in-law, William De Forest, who was a wealthy woolen manufacturer, took Ryder's place. The work of making the invention practical was continued. In 1844 the process was sufficiently perfected that Goodyear felt it safe to take out a patent, although Goodyear spent upwards of $50,000 to research costs to achieve this result. The factory at Springfield was run by his brothers, Nelson and Henry. In 1843 Henry started a new factory in Naugatuck, and in 1844 introduced mechanical mixing of the mixture in place of the use of solvents. Goodyear also invented a material composed of a mixture of vulcanized rubber and cotton fiber which could easily be fashioned into durable sheets for the production of rubber goods.

Goodyear eventually declared bankruptcy to settle debts that had accumulated during his leaner years. He is said to have repaid $35,000 to his creditors. <<<Iles 1912, 197.>>>

In 1851, Good year received the great council medal at the London Exhibition for his rubber products.

Unfortunately, Goodyear's finances did not improve substantially in subsequent years. He had trouble enforcing compliance with his American patents, and he eventually lost some of his European patents.

In Great Britain, Thomas Hancock claimed to have reinvented vulcanization and secured patents there, although he admitted in evidence that the first piece of vulcanized rubber he ever saw came from America.

In 1852 a French company (Aigle) was licensed by Mr. Goodyear to make shoes, and a great deal of interest was felt in the new business. In 1855 the French emperor gave to Charles Goodyear the Grand Medal of Honor and decorated him with the Cross of the Legion of Honor in recognition of his services as a public benefactor. Later, the French courts subsequently set aside his French patents on the ground of the importation of vulcanized goods from America by licenses under the United States patents.

In the United States, however, Goodyear patented over 60 inventions and processes during his career, and was continually perfecting the products he produced. <<<Hubert 1893, 175.>>>

Death

Goodyear died July 1, 1860, while traveling to see his dying daughter. After arriving in New York, he was informed that she had already died. He collapsed and was taken to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City, where he died at the age of fifty-nine. He is buried in New Haven at Grove Street Cemetery. He left his family saddled with debts, and an attempt to have his patents extended by for the benefit of his children was unsuccessful.

Among his seven children was Professor William Henry Goodyear, who became curator of the Department of Fine Arts of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. A grandson, Charles Goodyear, was the inventor of several processes involving acetylene. <<<Iles 1912, 178.>>>

Legacy

In 1898, almost four decades after his death, the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company was founded and named after Goodyear by Frank Seiberling.

On February 8, 1976, he was among 6 selected for induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

In his hometown of Woburn, Massachusetts, there is an elementary school named after him.

See also

- Rubber

- Vulcanization

Notes

- ↑ Hosler, D., Burkett, S. L., and Tarkanian, M. J. (1999). "Prehistoric polymers: Rubber processing in ancient Mesoamerica," Science, 284(5422), pp. 1988 - 1991.

- ↑ Slack, Charles (2003). Noble Obsession, 225, Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8856-3.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 787, January 31, 1891 on Project Gutenberg

- The Charles Goodyear Story

External links

- The Charles Goodyear Story

- Raw Deal

- Today in Science History - Goodyear's U.S. Patent No. 240: Improvement in the Process of Divesting Caoutchouc, Gum-Elastic, or India-Rubber of its Adhesive Properties, and also of Bleaching the Same, and Thereby Adapting it to Various Useful Purposes.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.