Difference between revisions of "Caedmon" - New World Encyclopedia

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{status}} | |

| − | '''Cædmon''' is the earliest English [[English poetry|poet]] whose name is known. An [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] | + | '''Cædmon''' is the earliest English [[English poetry|poet]] whose name is known. An [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] herdsman attached to the [[monastery]] of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda (657–681), he was originally ignorant of "the art of song"; but, according to legend, he learned to compose one night in the course of a dream. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational religious poet. |

Cædmon is one of twelve [[Anglo-Saxon Poetry|Anglo-Saxon poets]] identified in medieval sources, and one of only three for whom both roughly contemporary biographical information and examples of literary output have survived.<ref>The twelve named Anglo-Saxon poets are Æduwen, Aldhelm, [[King Alfred|Alfred]], Anlaf, Baldulf, [[Bede]], Cædmon, Cnut, [[Cynewulf]], Dunstan, Hereward, and Wulfstan. The three for whom biographical information and documented texts survive are [[Alfred]], [[Bede]], and Cædmon. Cædmon is the only Anglo-Saxon poet known primarily for his ability to compose vernacular verse. (No study appears to exist of the "named" Anglo-Saxon poets—the list here has been compiled from [[#frank1993|Frank 1993]], [[#opland1980|Opland 1980]], [[#sisam1953|Sisam 1953]] and [[#robinson1990|Robinson 1990]]).</ref> His story is related in the ''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum'' ("Ecclesiastical History of the English People") by [[Bede|St. Bede]] who wrote, "There was in the Monastery of this Abbess a certain brother particularly remarkable for the Grace of God, who was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of [[Bible|scripture]], he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in [[English language|English]], which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven." | Cædmon is one of twelve [[Anglo-Saxon Poetry|Anglo-Saxon poets]] identified in medieval sources, and one of only three for whom both roughly contemporary biographical information and examples of literary output have survived.<ref>The twelve named Anglo-Saxon poets are Æduwen, Aldhelm, [[King Alfred|Alfred]], Anlaf, Baldulf, [[Bede]], Cædmon, Cnut, [[Cynewulf]], Dunstan, Hereward, and Wulfstan. The three for whom biographical information and documented texts survive are [[Alfred]], [[Bede]], and Cædmon. Cædmon is the only Anglo-Saxon poet known primarily for his ability to compose vernacular verse. (No study appears to exist of the "named" Anglo-Saxon poets—the list here has been compiled from [[#frank1993|Frank 1993]], [[#opland1980|Opland 1980]], [[#sisam1953|Sisam 1953]] and [[#robinson1990|Robinson 1990]]).</ref> His story is related in the ''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum'' ("Ecclesiastical History of the English People") by [[Bede|St. Bede]] who wrote, "There was in the Monastery of this Abbess a certain brother particularly remarkable for the Grace of God, who was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of [[Bible|scripture]], he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in [[English language|English]], which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven." | ||

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | Cædmon's only known surviving work is ''Cædmon's Hymn'', the nine-line alliterative praise poem in | + | Cædmon's only known surviving work is ''Cædmon's Hymn'', the nine-line alliterative praise poem in honor of God that he supposedly learned to sing in his initial dream. The poem is one of the earliest attested examples of the Old English language, and is also one earliest recorded examples of sustained [[poetry]] in a Germanic language. Although almost nothing of Caedmon's work has survived to the present day, his influence, as attested by both contemporary and medieval sources, appears to have been extraordinary. Although it is debatable whether Caedmon was the first true English poet, he is certainly the earliest English poet to be preserved in history. Although knowledge of the literature of Caedmon's time has all but vanished, along with almost all knowledge of English literature prior to 1066, he is indubitably a major influence on Old English literature. Much like [[Sappho]], another poet of the ancient world whose works are almost entirely lost, Caedmon exists for us now almost more as a legend than as an actual writer; yet even so, his importance to English literary history cannot be denied. |

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

===Bede's account=== | ===Bede's account=== | ||

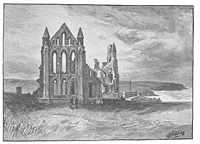

| − | The sole source of original information about Cædmon's life and work is [[Bede]]'s '' | + | The sole source of original information about Cædmon's life and work is [[Bede]]'s ''Historia ecclesiastica''.<ref>Book IV, Chapter 24. The most recent edition is [[#colgraveandmynors1969|Colgrave and Mynors 1969]].</ref> According to Bede, Cædmon was a lay brother who worked as a herdsman at the monastery Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey).{{GBthumb|132|127|SU123422}} Whitby (shown at right) is a town on the [[North Sea]], on the northeast coast of North Yorkshire. One evening, while the monks were feasting, singing, and playing a harp, Cædmon left early to sleep with the animals because he knew no songs. While asleep, he had a dream in which "someone" ''(quidem)'' approached him and asked him to sing ''principium creaturarum'', "the beginning of created things." After first refusing to sing, Cædmon subsequently produced a short eulogistic poem praising God as the creator of heaven and earth. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Whitby Abbey - Project Gutenberg eText 16785.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Ruins of Streonæshalch (Whitby Abbey) in North Yorkshire, England — founded in 657 by [[St. Hilda]], the abbey fell to a [[viking]] attack in 867 and was abandoned. It was re-built in 1078 and flourished until 1540 when it was destroyed by [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]].]] | |

| − | Upon awakening the next morning, Cædmon remembered everything he had sung and added additional lines to his poem. He told his foreman about his dream and gift and was taken immediately to see the | + | Upon awakening the next morning, Cædmon remembered everything he had sung and added additional lines to his poem. He told his foreman about his dream and gift and was taken immediately to see the abbess. The abbess and her counsellors asked Cædmon about his vision and, satisfied that it was a gift from God, gave him a new commission, this time for a poem based on “a passage of sacred history or doctrine,” by way of a test. When Cædmon returned the next morning with the requested poem, he was ordered to take monastic vows. The abbess ordered her scholars to teach Cædmon sacred history and doctrine, which after a night of thought, Bede records, Cædmon would turn into the most beautiful verse. According to Bede, Cædmon was responsible for a large oeuvre of splendid vernacular poetic texts on a variety of Christian topics. |

| − | After a long and zealously pious life, Cædmon died like a saint | + | After a long and zealously pious life, Cædmon died like a saint; receiving a premonition of death, he asked to be moved to the abbey’s hospice for the terminally ill where he gathered his friends around him and expired just before nocturns. |

===Dates=== | ===Dates=== | ||

| − | Bede gives no specific dates in his story. | + | Bede gives no specific dates in his story. Cædmon is said to have taken holy orders at an advanced age and it is implied that he lived at Streonæshalch at least during part of Hilda’s abbacy (657–680). Book IV Chapter 25 of the ''Historia ecclesiastica'' appears to suggest that Cædmon’s death occurred sometime roughly around 679.<ref>See [[#ireland1986|Ireland 1986]], pp. 228; [[#dumville1981|Dumville 1981]], p. 148.</ref> The next datable event in the ''Historia ecclesiastica'' is King Ecgfrith’s raid on [[Ireland]] in 684 (Book IV, Chapter 26). Taken together, this evidence suggests an active period beginning between 657 and 680 and ending between 679 and 684. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====The Heliand==== | ====The Heliand==== | ||

| − | A second, possibly pre- | + | A second, possibly pre-twelfth-century allusion to the Cædmon story is found in two Latin texts associated with the Old Saxon ''Heliand'' poem originating from present-day Germany. These texts, the ''Praefatio'' (Preface) and ''Versus de Poeta'' (Lines about the poet), explain the origins of an Old Saxon biblical translation (for which the ''Heliand'' is the only known candidate)<ref>[[#andersson1974|Andersson 1974]], p. 278.</ref> in language strongly reminiscent of, and indeed at times identical to, Bede’s account of Cædmon’s career.<ref>Convenient accounts of the relevant portions of the ''Praefatio'' and ''Versus'' can be found in [[#smith1978|Smith 1978]], pp. 13–14, and [[#plummer1896|Plummer 1896]] II pp. 255–258.</ref> According to the prose ''Praefatio'', the Old Saxon poem was composed by a renowned vernacular poet at the command of the emperor Louis the Pious; the text adds that this poet had known nothing of vernacular composition until he was ordered to translate the precepts of sacred law into vernacular song in a dream. The ''Versus de Poeta'' contain an expanded account of the dream itself, adding that the poet had been a herdsman before his inspiration and that the inspiration itself had come through the medium of a heavenly voice when he fell asleep after pasturing his cattle. While our knowledge of these texts is based entirely on a sixteenth-century edition by Flacius Illyricus,<ref>[[#catalogustestiumueritatis1562|Catalogus testium ueritatis 1562]].</ref> both are usually assumed on semantic and grammatical grounds to be of medieval composition.<ref>See [[#andersson1974|Andersson 1974]] for a review of the evidence for and against the authenticity of the prefaces.</ref> This apparent debt to the Cædmon story agrees with semantic evidence attested to by Green demonstrating the influence of Anglo Saxon biblical poetry and terminology on early continental Germanic literatures.<ref>See [[#green1965|Green 1965]], particularly pp. 286–294.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Work== | ==Work== | ||

===General corpus=== | ===General corpus=== | ||

| − | Bede’s account indicates that Cædmon was responsible for the composition of a large | + | Bede’s account indicates that Cædmon was responsible for the composition of a large oeuvre of vernacular religious poetry. In contrast to the contemporary poets Aldhelm and Dunstan,<ref>On whose careers as vernacular poets in comparison to that of Cædmon, see [[#opland1980|Opland 1980]], pp. 120–127 and 178–180.</ref> Cædmon’s poetry is said to have been exclusively religious. Bede reports that Cædmon “could never compose any foolish or trivial poem, but only those which were concerned with devotion” and his list of Cædmon’s output includes work on religious subjects only: accounts of creation, translations from the Old and New Testaments, and songs about the “terrors of future judgment, horrors of hell, … joys of the heavenly kingdom, … and divine mercies and judgments.” Of this corpus, only the opening lines of his first poem survive. While vernacular poems matching Bede’s description of several of Cædmon’s later works are found in the Junius manuscript, the older traditional attribution of these texts to Cædmon or Cædmon’s influence cannot stand. The poems show significant stylistic differences both internally and with Cædmon’s original ''Hymn'',<ref>See [[#wrenn1946|Wrenn 1946]]</ref> and, while some of the poems contained therein could have been written by Caedmon, the match is not exact enough to preclude independent composition. |

===''Cædmon's Hymn''=== | ===''Cædmon's Hymn''=== | ||

[[Image:Caedmon's Hymn Moore mine01.gif|450 px|thumb|right|One of two candidates for the earliest surviving copy of ''Cædmon's Hymn'' is found in "The Moore Bede" (ca. 737) which is held by the [[Cambridge University Library]] (Kk. 5. 16, often referred to as '''M'''). The other candidate is St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, lat. Q. v. I. 18 (P)]] | [[Image:Caedmon's Hymn Moore mine01.gif|450 px|thumb|right|One of two candidates for the earliest surviving copy of ''Cædmon's Hymn'' is found in "The Moore Bede" (ca. 737) which is held by the [[Cambridge University Library]] (Kk. 5. 16, often referred to as '''M'''). The other candidate is St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, lat. Q. v. I. 18 (P)]] | ||

| − | The only known survivor from Cædmon’s oeuvre is his ''Hymn'' ([http://www.wwnorton.com/nael/noa/realmedia/CademonsHymn.rm audio version]<ref> | + | The only known survivor from Cædmon’s oeuvre is his ''Hymn'' ([http://www.wwnorton.com/nael/noa/realmedia/CademonsHymn.rm audio version]<ref>The Norton Online Archive of English Literature, ''Caedmon's Hymn'' recorded by Prof. Robert D. Fulk (Indiana University) [http://www.wwnorton.com/nael/noa/realmedia/CademonsHymn.rm Online] Retrieved April 26, 2006.</ref>). The poem is known from twenty-one manuscript copies, making it the best-attested Old English poem after Bede’s ''Death Song'' and the best attested in the poetic corpus in manuscripts copied or owned in the British Isles during the Anglo-Saxon period. The ''Hymn'' also has by far the most complicated known textual history of any surviving Anglo-Saxon poem. It is one of the earliest attested examples of written Old English and one of the earliest recorded examples of sustained poetry in a Germanic language.<ref>[[#stanley1995|Stanley 1995]], p. 139.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The following text has been transcribed from '''M''' (mid- | + | ====Text of the Poem==== |

| + | The oldest known version of the poem is the Northumbrian ''aelda'' recension. The following text has been transcribed from the '''M''' manuscript (mid-eighth century; Northumbria). The text has been normalized to show modern punctuation and line- and word-division: | ||

<div class="notice spoilerbox"><table width=85% border="0"><tr><td align=center><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | <div class="notice spoilerbox"><table width=85% border="0"><tr><td align=center><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | ||

| Line 69: | Line 49: | ||

:''Now <nowiki>[we]</nowiki> must honour the guardian of heaven,'' | :''Now <nowiki>[we]</nowiki> must honour the guardian of heaven,'' | ||

:''the might of the architect, and his purpose,'' | :''the might of the architect, and his purpose,'' | ||

| − | :''the work of the father of glory'' | + | :''the work of the father of glory'' |

| − | :'' | + | :''—as he, the eternal lord, established the beginning of wonders.'' |

:''He, the holy creator,'' | :''He, the holy creator,'' | ||

| − | :''first created heaven as a roof for the children of men. | + | :''first created heaven as a roof for the children of men.'' |

| − | |||

:''the lord almighty, afterwards appointed the middle earth,'' | :''the lord almighty, afterwards appointed the middle earth,'' | ||

| − | :''the lands, for men.'' | + | :''the lands, for men.'' |

{{col-end}} | {{col-end}} | ||

</div></td></tr></table></div> | </div></td></tr></table></div> | ||

| Line 87: | Line 66: | ||

<div class="references-small"> | <div class="references-small"> | ||

*<span id="andersson1974">Andersson, Th. M. 1974. "The Cædmon fiction in the ''Heliand'' Preface" ''Publications of the Modern Language Association'' 89:278–84.</span> | *<span id="andersson1974">Andersson, Th. M. 1974. "The Cædmon fiction in the ''Heliand'' Preface" ''Publications of the Modern Language Association'' 89:278–84.</span> | ||

| − | *<span id="ball1985">Ball, C.J.E. 1985. "Homonymy and polysemy in Old English: A problem for lexicographers." In | + | *<span id="ball1985">Ball, C. J. E. 1985. "Homonymy and polysemy in Old English: A problem for lexicographers." In ''Problems of Old English lexicography: studies in memory of Angus Cameron'', ed. A. Bammesberger. Eichstätter Beiträge, 15. 39–46. Regensburg: Pustet.</span> ISBN 3791709925 |

| − | *<span id="bessinger1974">Bessinger, J. B. Jr. 1974. "Homage to Cædmon and others: A Beowulfian praise song." In | + | *<span id="bessinger1974">Bessinger, J. B. Jr. 1974. "Homage to Cædmon and others: A Beowulfian praise song." In ''Old English Studies in Honour of John C. Pope'', eds. Robert B. Burlin, Edward B. Irving, Jr. and Marie Borroff. 91–106. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.</span> ISBN 0802021328 |

| − | *<span id="colgraveandmynors1969">Colgrave, B. and R.A.B. Mynors | + | *<span id="colgraveandmynors1969">Colgrave, B. and R. A. B. Mynors (eds.). 1969. ''Bede's Ecclesiastical history of the English people''. Oxford: OUP.</span> ASIN B000H7E7BY |

*<span id="day1975">Day, V. 1975. "The influence of the catechetical ''narratio'' on Old English and some other medieval literature" ''Anglo-Saxon England'' 3: 51–61.</span> | *<span id="day1975">Day, V. 1975. "The influence of the catechetical ''narratio'' on Old English and some other medieval literature" ''Anglo-Saxon England'' 3: 51–61.</span> | ||

*<span id="dobbie1937">Dobbie, E. v. K. 1937. "The manuscripts of ''Cædmon's Hymn'' and ''Bede's Death Song'' with a critical text of the ''Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae''. Columbia University Studies in English and Comparative Literature 128. New York: Columbia.</span> | *<span id="dobbie1937">Dobbie, E. v. K. 1937. "The manuscripts of ''Cædmon's Hymn'' and ''Bede's Death Song'' with a critical text of the ''Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae''. Columbia University Studies in English and Comparative Literature 128. New York: Columbia.</span> | ||

| − | *<span id="dumville1981">Dumville, D. 1981. "'Beowulf' and the Celtic world: The uses of evidence" | + | *<span id="dumville1981">Dumville, D. 1981. "'Beowulf' and the Celtic world: The uses of evidence." ''Traditio'' 37: 109–160.</span> |

| − | *<span id="frank1993">Frank, R. 1993. "The search for the Anglo-Saxon oral poet" | + | *<span id="frank1993">Frank, R. 1993. "The search for the Anglo-Saxon oral poet" (T. Northcote Toller memorial lecture; March 9, 1992). 'Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library'' 75: 11-36.</span> |

| − | *<span id="fritz1969">Fritz, D. W. 1969. "Cædmon: A traditional Christian poet" | + | *<span id="fritz1969">Fritz, D. W. 1969. "Cædmon: A traditional Christian poet." ''Mediaevalia'' 31: 334–337.</span> |

| − | *<span id="fry1975">Fry, D. K. 1975. "Caedmon as formulaic poet" | + | *<span id="fry1975">Fry, D. K. 1975. "Caedmon as formulaic poet." In ''Oral literature: Seven essays''. Ed. J.J. Duggan. 41–61. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.</span> ISBN 0701121149 |

| − | *<span id="fry1979">Fry, D. K. 1979. "Old English formulaic statistics" | + | *<span id="fry1979">Fry, D. K. 1979. "Old English formulaic statistics." ''In Geardagum'' 3: 1–6.</span> ISBN 0936072059 |

| − | *<span id="gollancz1927"> | + | *<span id="gollancz1927">Gollancz, I. (ed.). 1927. ''The Cædmon manuscript of Anglo-Saxon biblical poetry: Junius XI in the Bodleian Library''. Oxford: British Academy.</span> |

| − | *<span id="1965">Green, D. H. 1965''The Carolingian lord: Semantic studies on four Old High German words: ''Balder'', ''Frô'', ''Truhtin'', ''Hêrro''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. </span> | + | *<span id="1965">Green, D. H. 1965. ''The Carolingian lord: Semantic studies on four Old High German words: ''Balder'', ''Frô'', ''Truhtin'', ''Hêrro''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. </span> |

| − | *<span id="hieatt1985">Hieatt, C. B. 1985. "Cædmon in context: Transforming the formula" | + | *<span id="hieatt1985">Hieatt, C. B. 1985. "Cædmon in context: Transforming the formula." ''Journal of English and Germanic Philology'' 84: 485–497.</span> |

| − | *<span id="howlett1974">Howlett, D. R. 1974. "The theology of Caedmon's Hymn" | + | *<span id="howlett1974">Howlett, D. R. 1974. "The theology of Caedmon's Hymn." ''Leeds Studies in English'' 7: 1–12.</span> |

| − | *<span id="humphreysandross1975">Humphreys, K. W. and A. S. C. Ross. 1975. "Further manuscripts of Bede's 'Historia ecclesiastica', of the 'Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae', and further Anglo-Saxon texts of 'Cædmon's Hymn' and 'Bede's Death Song'" | + | *<span id="humphreysandross1975">Humphreys, K. W. and A. S. C. Ross. 1975. "Further manuscripts of Bede's 'Historia ecclesiastica', of the 'Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae', and further Anglo-Saxon texts of 'Cædmon's Hymn' and 'Bede's Death Song'." ''Notes and Queries'' 220: 50–55.</span> |

| − | *<span id="ireland1986">Ireland, C. A. 1986. "The Celtic background to the story of Caedmon and his Hymn" | + | *<span id="ireland1986">Ireland, C. A. 1986. "The Celtic background to the story of Caedmon and his Hymn." Unpublished Ph.D. diss. UCLA.</span> |

*<span id="jackson1953">Jackson, K. 1953. ''Language and history in early Britain''. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.</span> | *<span id="jackson1953">Jackson, K. 1953. ''Language and history in early Britain''. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.</span> | ||

| − | *<span id="klaeber1912">Klaeber, F. 1912. "Die Christlichen Elemente im Beowulf" | + | *<span id="klaeber1912">Klaeber, F. 1912. "Die Christlichen Elemente im Beowulf." ''Anglia'' 35: 111–136.</span> |

| − | *<span id="lester1974">Lester, G. A. 1974. "The Cædmon story and its analogues" | + | *<span id="lester1974">Lester, G. A. 1974. "The Cædmon story and its analogues." ''Neophilologus'' 58: 225–237.</span> |

| − | *<span id="miletich1983">Miletich, J. S. 1983. "Old English 'formulaic' studies and Cædmon's Hymn in a comparative context" | + | *<span id="miletich1983">Miletich, J. S. 1983. "Old English 'formulaic' studies and Cædmon's Hymn in a comparative context." In ''Festschrift für Nikola R. Pribic'', eds. Josip Matesic and Erwin Wendel. Selecta Slav., 9. 183–194. Neuried: Hiernoymous.</span> |

*<span id="mitchell1985">Mitchell, B. 1985. "Cædmon's Hymn line 1: What is the subject of scylun or its variants?" ''Leeds Studies in English'' 16: 190–197.</span> | *<span id="mitchell1985">Mitchell, B. 1985. "Cædmon's Hymn line 1: What is the subject of scylun or its variants?" ''Leeds Studies in English'' 16: 190–197.</span> | ||

| − | *<span id="morland1992">Morland, L. 1992. "Cædmon and the Germanic tradition" | + | *<span id="morland1992">Morland, L. 1992. "Cædmon and the Germanic tradition." In ''De Gustibus: Essays for Alain Renoir'', eds. John Miles Foley, J. Chris Womack, and Whitney A. Womack. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 1482. 324–358. New York: Garland. </span> |

| − | *<span id="odonnell1996">O'Donnell, D. P. 1996. "A Northumbrian version of 'Cædmon's Hymn' (Northumbrian ''eordu'' recension) in Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale MS 8245-57, ff. 62r2-v1: Identification, edition, and filiation." In | + | *<span id="odonnell1996">O'Donnell, D. P. 1996. "A Northumbrian version of 'Cædmon's Hymn' (Northumbrian ''eordu'' recension) in Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale MS 8245-57, ff. 62r2-v1: Identification, edition, and filiation." In ''Beda Venerabilis: Historian, monk, and Northumbrian'', eds. L. A. J. R. Houwen and A.A. MacDonald Mediaevalia Groningana 19. 139–165. Groningen: Forsten.</span> |

*<span id="odonnell2005">O'Donnell, D. P. 2005. ''Cædmon’s Hymn, A multimedia study, edition, and witness archive''. SEENET A. 7. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.</span> | *<span id="odonnell2005">O'Donnell, D. P. 2005. ''Cædmon’s Hymn, A multimedia study, edition, and witness archive''. SEENET A. 7. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.</span> | ||

| − | *<span id="ohare1992">O'Hare, C. 1992. "The story of Cædmon: Bede's account of the first English poet" | + | *<span id="ohare1992">O'Hare, C. 1992. "The story of Cædmon: Bede's account of the first English poet." ''American Benedictine Review'' 43: 345–57.</span> |

*<span id="okeeffe1990">O'Keeffe, K. O’B. 1990. ''Visible song: Transitional literacy in Old English verse''. Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.</span> | *<span id="okeeffe1990">O'Keeffe, K. O’B. 1990. ''Visible song: Transitional literacy in Old English verse''. Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.</span> | ||

*<span id="opland1980">Opland, J. 1980. ''Anglo-Saxon oral poetry: A study of the traditions''. New Haven: Yale University Press. </span> | *<span id="opland1980">Opland, J. 1980. ''Anglo-Saxon oral poetry: A study of the traditions''. New Haven: Yale University Press. </span> | ||

| − | *<span id="orton1998">Orton, P. 1998. "The transmission of the West-Saxon versions of ''Cædmon's Hymn'': A reappraisal" | + | *<span id="orton1998">Orton, P. 1998. "The transmission of the West-Saxon versions of ''Cædmon's Hymn'': A reappraisal." ''Studia Neophilologica'' 70: 153–164.</span> |

| − | *<span id="palgrave1832"> | + | *<span id="palgrave1832">Palgrave, F. 1832. "Observations on the history of Cædmon." ''Archaeologia'' 24: 341-342.</span> |

| − | *<span id="plummer1896"> | + | *<span id="plummer1896">Plummer, C. (ed.). 1896. ''Venerabilis Baedae: Historiam ecclesiasticam gentis anglorum, historiam abbatum, epistolam ad Ecgberctum una cum historia abbatum''. Oxford.</span> |

| − | *<span id="pound1929">Pound, L. 1929. "Cædmon's dream song" | + | *<span id="pound1929">Pound, L. 1929. "Cædmon's dream song." In ''Studies in English philology: A miscellany in honor of Frederick Klaeber'', eds. Kemp Malone and Martin B. Ruud. 232–239. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.</span> |

| − | *<span id="robinson1990">Robinson, F.C | + | *<span id="robinson1990">Robinson, F.C. 1990. "Old English poetry: the question of authorship." ''ANQ'' n.s. 3: 59-64.</span> |

*<span id="schwab1972">Schwab, U. 1972. ''Cædmon''. Testi e Studi: Pubblicazioni dell'Istituto di Lingue e Letterature Germanische, Università di Messina. Messina: Peloritana Editrice.</span> | *<span id="schwab1972">Schwab, U. 1972. ''Cædmon''. Testi e Studi: Pubblicazioni dell'Istituto di Lingue e Letterature Germanische, Università di Messina. Messina: Peloritana Editrice.</span> | ||

*<span id="sisam1953">Sisam, K. 1953. ''Studies in the history of Old English literature''. Oxford: Clarendon Press</span>. | *<span id="sisam1953">Sisam, K. 1953. ''Studies in the history of Old English literature''. Oxford: Clarendon Press</span>. | ||

| − | *<span id="smith1978">Smith, A.H. | + | *<span id="smith1978">Smith, A.H. (ed.). 1978. ''Three Northumbrian poems: Cædmon's Hymn, Bede's Death Song and the Leiden Riddle''. With a bibliography compiled by M.J. Swanton. Revised Edition. Exeter Medieval English Texts and Studies. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.</span> |

| − | *<span id="whitelock1963">Whitelock, D. 1963. "'The Old English Bede" | + | *<span id="whitelock1963">Whitelock, D. 1963. "'The Old English Bede." Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1962. ''Proceedings of the British Academy'' 48: 57–93.</span> |

| − | *<span id="wrenn1946"> | + | *<span id="wrenn1946">Wrenn, C. L. "The poetry of Cædmon." Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1945. ''Proceedings of the British Academy'' 32: 277–295.</span> |

</div> | </div> | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 25, 2023. | ||

| + | |||

*[http://www.heorot.dk/bede-caedmon.html Bede's Story of Caedmon] | *[http://www.heorot.dk/bede-caedmon.html Bede's Story of Caedmon] | ||

*[http://www.bedesworld.co.uk/ Bede's World] | *[http://www.bedesworld.co.uk/ Bede's World] | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.wilfrid.com/saints/hilda.htm St. Hilda and Caedmon Page at St. Wilfrid's] | *[http://www.wilfrid.com/saints/hilda.htm St. Hilda and Caedmon Page at St. Wilfrid's] | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[category:biography]] |

| + | [[category:Writers and poets]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{credit|78588223}} | {{credit|78588223}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:15, 25 November 2023

Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. An Anglo-Saxon herdsman attached to the monastery of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda (657–681), he was originally ignorant of "the art of song"; but, according to legend, he learned to compose one night in the course of a dream. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational religious poet.

Cædmon is one of twelve Anglo-Saxon poets identified in medieval sources, and one of only three for whom both roughly contemporary biographical information and examples of literary output have survived.[1] His story is related in the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum ("Ecclesiastical History of the English People") by St. Bede who wrote, "There was in the Monastery of this Abbess a certain brother particularly remarkable for the Grace of God, who was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in English, which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven."

Cædmon's only known surviving work is Cædmon's Hymn, the nine-line alliterative praise poem in honor of God that he supposedly learned to sing in his initial dream. The poem is one of the earliest attested examples of the Old English language, and is also one earliest recorded examples of sustained poetry in a Germanic language. Although almost nothing of Caedmon's work has survived to the present day, his influence, as attested by both contemporary and medieval sources, appears to have been extraordinary. Although it is debatable whether Caedmon was the first true English poet, he is certainly the earliest English poet to be preserved in history. Although knowledge of the literature of Caedmon's time has all but vanished, along with almost all knowledge of English literature prior to 1066, he is indubitably a major influence on Old English literature. Much like Sappho, another poet of the ancient world whose works are almost entirely lost, Caedmon exists for us now almost more as a legend than as an actual writer; yet even so, his importance to English literary history cannot be denied.

Life

Bede's account

The sole source of original information about Cædmon's life and work is Bede's Historia ecclesiastica.[2] According to Bede, Cædmon was a lay brother who worked as a herdsman at the monastery Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey).

Map sources for Caedmon at grid reference SU123422

|

Whitby (shown at right) is a town on the North Sea, on the northeast coast of North Yorkshire. One evening, while the monks were feasting, singing, and playing a harp, Cædmon left early to sleep with the animals because he knew no songs. While asleep, he had a dream in which "someone" (quidem) approached him and asked him to sing principium creaturarum, "the beginning of created things." After first refusing to sing, Cædmon subsequently produced a short eulogistic poem praising God as the creator of heaven and earth.

Upon awakening the next morning, Cædmon remembered everything he had sung and added additional lines to his poem. He told his foreman about his dream and gift and was taken immediately to see the abbess. The abbess and her counsellors asked Cædmon about his vision and, satisfied that it was a gift from God, gave him a new commission, this time for a poem based on “a passage of sacred history or doctrine,” by way of a test. When Cædmon returned the next morning with the requested poem, he was ordered to take monastic vows. The abbess ordered her scholars to teach Cædmon sacred history and doctrine, which after a night of thought, Bede records, Cædmon would turn into the most beautiful verse. According to Bede, Cædmon was responsible for a large oeuvre of splendid vernacular poetic texts on a variety of Christian topics.

After a long and zealously pious life, Cædmon died like a saint; receiving a premonition of death, he asked to be moved to the abbey’s hospice for the terminally ill where he gathered his friends around him and expired just before nocturns.

Dates

Bede gives no specific dates in his story. Cædmon is said to have taken holy orders at an advanced age and it is implied that he lived at Streonæshalch at least during part of Hilda’s abbacy (657–680). Book IV Chapter 25 of the Historia ecclesiastica appears to suggest that Cædmon’s death occurred sometime roughly around 679.[3] The next datable event in the Historia ecclesiastica is King Ecgfrith’s raid on Ireland in 684 (Book IV, Chapter 26). Taken together, this evidence suggests an active period beginning between 657 and 680 and ending between 679 and 684.

The Heliand

A second, possibly pre-twelfth-century allusion to the Cædmon story is found in two Latin texts associated with the Old Saxon Heliand poem originating from present-day Germany. These texts, the Praefatio (Preface) and Versus de Poeta (Lines about the poet), explain the origins of an Old Saxon biblical translation (for which the Heliand is the only known candidate)[4] in language strongly reminiscent of, and indeed at times identical to, Bede’s account of Cædmon’s career.[5] According to the prose Praefatio, the Old Saxon poem was composed by a renowned vernacular poet at the command of the emperor Louis the Pious; the text adds that this poet had known nothing of vernacular composition until he was ordered to translate the precepts of sacred law into vernacular song in a dream. The Versus de Poeta contain an expanded account of the dream itself, adding that the poet had been a herdsman before his inspiration and that the inspiration itself had come through the medium of a heavenly voice when he fell asleep after pasturing his cattle. While our knowledge of these texts is based entirely on a sixteenth-century edition by Flacius Illyricus,[6] both are usually assumed on semantic and grammatical grounds to be of medieval composition.[7] This apparent debt to the Cædmon story agrees with semantic evidence attested to by Green demonstrating the influence of Anglo Saxon biblical poetry and terminology on early continental Germanic literatures.[8]

Work

General corpus

Bede’s account indicates that Cædmon was responsible for the composition of a large oeuvre of vernacular religious poetry. In contrast to the contemporary poets Aldhelm and Dunstan,[9] Cædmon’s poetry is said to have been exclusively religious. Bede reports that Cædmon “could never compose any foolish or trivial poem, but only those which were concerned with devotion” and his list of Cædmon’s output includes work on religious subjects only: accounts of creation, translations from the Old and New Testaments, and songs about the “terrors of future judgment, horrors of hell, … joys of the heavenly kingdom, … and divine mercies and judgments.” Of this corpus, only the opening lines of his first poem survive. While vernacular poems matching Bede’s description of several of Cædmon’s later works are found in the Junius manuscript, the older traditional attribution of these texts to Cædmon or Cædmon’s influence cannot stand. The poems show significant stylistic differences both internally and with Cædmon’s original Hymn,[10] and, while some of the poems contained therein could have been written by Caedmon, the match is not exact enough to preclude independent composition.

Cædmon's Hymn

The only known survivor from Cædmon’s oeuvre is his Hymn (audio version[11]). The poem is known from twenty-one manuscript copies, making it the best-attested Old English poem after Bede’s Death Song and the best attested in the poetic corpus in manuscripts copied or owned in the British Isles during the Anglo-Saxon period. The Hymn also has by far the most complicated known textual history of any surviving Anglo-Saxon poem. It is one of the earliest attested examples of written Old English and one of the earliest recorded examples of sustained poetry in a Germanic language.[12]

Text of the Poem

The oldest known version of the poem is the Northumbrian aelda recension. The following text has been transcribed from the M manuscript (mid-eighth century; Northumbria). The text has been normalized to show modern punctuation and line- and word-division:

|

Notes

- ↑ The twelve named Anglo-Saxon poets are Æduwen, Aldhelm, Alfred, Anlaf, Baldulf, Bede, Cædmon, Cnut, Cynewulf, Dunstan, Hereward, and Wulfstan. The three for whom biographical information and documented texts survive are Alfred, Bede, and Cædmon. Cædmon is the only Anglo-Saxon poet known primarily for his ability to compose vernacular verse. (No study appears to exist of the "named" Anglo-Saxon poets—the list here has been compiled from Frank 1993, Opland 1980, Sisam 1953 and Robinson 1990).

- ↑ Book IV, Chapter 24. The most recent edition is Colgrave and Mynors 1969.

- ↑ See Ireland 1986, pp. 228; Dumville 1981, p. 148.

- ↑ Andersson 1974, p. 278.

- ↑ Convenient accounts of the relevant portions of the Praefatio and Versus can be found in Smith 1978, pp. 13–14, and Plummer 1896 II pp. 255–258.

- ↑ Catalogus testium ueritatis 1562.

- ↑ See Andersson 1974 for a review of the evidence for and against the authenticity of the prefaces.

- ↑ See Green 1965, particularly pp. 286–294.

- ↑ On whose careers as vernacular poets in comparison to that of Cædmon, see Opland 1980, pp. 120–127 and 178–180.

- ↑ See Wrenn 1946

- ↑ The Norton Online Archive of English Literature, Caedmon's Hymn recorded by Prof. Robert D. Fulk (Indiana University) Online Retrieved April 26, 2006.

- ↑ Stanley 1995, p. 139.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andersson, Th. M. 1974. "The Cædmon fiction in the Heliand Preface" Publications of the Modern Language Association 89:278–84.

- Ball, C. J. E. 1985. "Homonymy and polysemy in Old English: A problem for lexicographers." In Problems of Old English lexicography: studies in memory of Angus Cameron, ed. A. Bammesberger. Eichstätter Beiträge, 15. 39–46. Regensburg: Pustet. ISBN 3791709925

- Bessinger, J. B. Jr. 1974. "Homage to Cædmon and others: A Beowulfian praise song." In Old English Studies in Honour of John C. Pope, eds. Robert B. Burlin, Edward B. Irving, Jr. and Marie Borroff. 91–106. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802021328

- Colgrave, B. and R. A. B. Mynors (eds.). 1969. Bede's Ecclesiastical history of the English people. Oxford: OUP. ASIN B000H7E7BY

- Day, V. 1975. "The influence of the catechetical narratio on Old English and some other medieval literature" Anglo-Saxon England 3: 51–61.

- Dobbie, E. v. K. 1937. "The manuscripts of Cædmon's Hymn and Bede's Death Song with a critical text of the Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae. Columbia University Studies in English and Comparative Literature 128. New York: Columbia.

- Dumville, D. 1981. "'Beowulf' and the Celtic world: The uses of evidence." Traditio 37: 109–160.

- Frank, R. 1993. "The search for the Anglo-Saxon oral poet" (T. Northcote Toller memorial lecture; March 9, 1992). 'Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library 75: 11-36.

- Fritz, D. W. 1969. "Cædmon: A traditional Christian poet." Mediaevalia 31: 334–337.

- Fry, D. K. 1975. "Caedmon as formulaic poet." In Oral literature: Seven essays. Ed. J.J. Duggan. 41–61. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. ISBN 0701121149

- Fry, D. K. 1979. "Old English formulaic statistics." In Geardagum 3: 1–6. ISBN 0936072059

- Gollancz, I. (ed.). 1927. The Cædmon manuscript of Anglo-Saxon biblical poetry: Junius XI in the Bodleian Library. Oxford: British Academy.

- Green, D. H. 1965. The Carolingian lord: Semantic studies on four Old High German words: Balder, Frô, Truhtin, Hêrro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hieatt, C. B. 1985. "Cædmon in context: Transforming the formula." Journal of English and Germanic Philology 84: 485–497.

- Howlett, D. R. 1974. "The theology of Caedmon's Hymn." Leeds Studies in English 7: 1–12.

- Humphreys, K. W. and A. S. C. Ross. 1975. "Further manuscripts of Bede's 'Historia ecclesiastica', of the 'Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae', and further Anglo-Saxon texts of 'Cædmon's Hymn' and 'Bede's Death Song'." Notes and Queries 220: 50–55.

- Ireland, C. A. 1986. "The Celtic background to the story of Caedmon and his Hymn." Unpublished Ph.D. diss. UCLA.

- Jackson, K. 1953. Language and history in early Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Klaeber, F. 1912. "Die Christlichen Elemente im Beowulf." Anglia 35: 111–136.

- Lester, G. A. 1974. "The Cædmon story and its analogues." Neophilologus 58: 225–237.

- Miletich, J. S. 1983. "Old English 'formulaic' studies and Cædmon's Hymn in a comparative context." In Festschrift für Nikola R. Pribic, eds. Josip Matesic and Erwin Wendel. Selecta Slav., 9. 183–194. Neuried: Hiernoymous.

- Mitchell, B. 1985. "Cædmon's Hymn line 1: What is the subject of scylun or its variants?" Leeds Studies in English 16: 190–197.

- Morland, L. 1992. "Cædmon and the Germanic tradition." In De Gustibus: Essays for Alain Renoir, eds. John Miles Foley, J. Chris Womack, and Whitney A. Womack. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 1482. 324–358. New York: Garland.

- O'Donnell, D. P. 1996. "A Northumbrian version of 'Cædmon's Hymn' (Northumbrian eordu recension) in Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale MS 8245-57, ff. 62r2-v1: Identification, edition, and filiation." In Beda Venerabilis: Historian, monk, and Northumbrian, eds. L. A. J. R. Houwen and A.A. MacDonald Mediaevalia Groningana 19. 139–165. Groningen: Forsten.

- O'Donnell, D. P. 2005. Cædmon’s Hymn, A multimedia study, edition, and witness archive. SEENET A. 7. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.

- O'Hare, C. 1992. "The story of Cædmon: Bede's account of the first English poet." American Benedictine Review 43: 345–57.

- O'Keeffe, K. O’B. 1990. Visible song: Transitional literacy in Old English verse. Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Opland, J. 1980. Anglo-Saxon oral poetry: A study of the traditions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Orton, P. 1998. "The transmission of the West-Saxon versions of Cædmon's Hymn: A reappraisal." Studia Neophilologica 70: 153–164.

- Palgrave, F. 1832. "Observations on the history of Cædmon." Archaeologia 24: 341-342.

- Plummer, C. (ed.). 1896. Venerabilis Baedae: Historiam ecclesiasticam gentis anglorum, historiam abbatum, epistolam ad Ecgberctum una cum historia abbatum. Oxford.

- Pound, L. 1929. "Cædmon's dream song." In Studies in English philology: A miscellany in honor of Frederick Klaeber, eds. Kemp Malone and Martin B. Ruud. 232–239. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Robinson, F.C. 1990. "Old English poetry: the question of authorship." ANQ n.s. 3: 59-64.

- Schwab, U. 1972. Cædmon. Testi e Studi: Pubblicazioni dell'Istituto di Lingue e Letterature Germanische, Università di Messina. Messina: Peloritana Editrice.

- Sisam, K. 1953. Studies in the history of Old English literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith, A.H. (ed.). 1978. Three Northumbrian poems: Cædmon's Hymn, Bede's Death Song and the Leiden Riddle. With a bibliography compiled by M.J. Swanton. Revised Edition. Exeter Medieval English Texts and Studies. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

- Whitelock, D. 1963. "'The Old English Bede." Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1962. Proceedings of the British Academy 48: 57–93.

- Wrenn, C. L. "The poetry of Cædmon." Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1945. Proceedings of the British Academy 32: 277–295.

External links

All links retrieved November 25, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.