Hutchinson, Anne

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) (import and credit) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (87 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} | ||

| + | {{epname|Hutchinson, Anne}} | ||

| + | |||

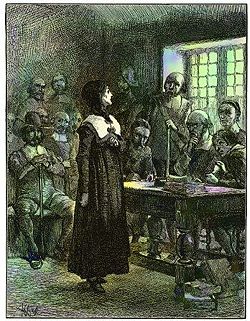

[[Image:Anne Hutchinson on Trial.jpg|thumb|right|250px|"Anne Hutchinson on Trial" by [[Edwin Austin Abbey]]]] | [[Image:Anne Hutchinson on Trial.jpg|thumb|right|250px|"Anne Hutchinson on Trial" by [[Edwin Austin Abbey]]]] | ||

| − | '''Anne Hutchinson''' (July, 1591 | + | '''Anne Marbury Hutchinson''' (July 17, 1591 - August 20, 1643) was a leading religious dissenter and nonconforming critic of the [[Puritan]] leadership of [[Massachusetts Bay]] colony. The daughter of a preacher who had been jailed several times in [[United Kingdom|England]] for subversive teaching, Hutchinson gathered a group of followers, first to discuss recent sermons but later challenging the religious authority of the colony's Puritan leadership. Claiming that salvation was exclusively the work of inner grace, Hutchinson disparaged the visible acts of moral conduct central to Puritan life as unnecessary to salvation. She was charged with the heresy of [[antinomianism]] and eventually banished from the colony with a group of her supporters. |

| − | + | They first settled the island of Aquidneck, which is now part of [[Rhode Island]]. Following her husband's death in 1642, Hutchinson and her six youngest children settled in what is now the Pelham Bay section of the [[Bronx]], in [[New York City]]. Like many settlers in the area, her family was caught in the middle of bloody reprisals which characterized the conflict between the [[Netherlands|Dutch]] and Indian tribes over the territory. She and five of those children were killed there in an attack by members of a Native [[Algonquian]] tribe in August 1643. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | Anne Hutchinson is often seen as an early American feminist who challenged a religious, male-dominated hierarchy based on an inner prompting. Her emphasis on grace over "works," while not inconsistent with Puritan theology, was interpreted as radical and divisive, partly because of her sharp criticisms of the colony's leadership and partly because women had subservient roles in the church and secular government in Puritan New England. | ||

| − | + | ==Early years and emigration to America== | |

| + | Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury on July 17, 1591, in Alford, Lincolnshire, [[England]]. She was the eldest daughter of Francis Marbury (1555-1611), a clergyman educated at Cambridge and Puritan reformer, and Bridget Dryden (1563-1645). In 1605, she moved with her family from Alford to [[London]]. | ||

| − | + | Anne's father observed a lack of competency among many of the ministers within the Church of England and concluded that they had not attained their positions through proper training, but for political reasons. Openly deploring this, he was eventually arrested for subversive activity, and spent a year in jail. This did not deter him, as he continued to speak out and continued to be arrested. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Anne, likely as a consequence, developed an interest in [[religion]] and [[theology]] at a very young age. It seemed she inherited her father's ideals and assertiveness, and wasn't afraid of questioning the principles of faith and the authority of the Church, as she would demonstrate in her later years.<ref>''Anne Hutchinson Website,'' [http://www.annehutchinson.com/anne_hutchinson_biography_001.htm Anne Hutchinson.] Retrieved January 18, 2008. </ref> | |

| − | Anne | ||

| − | At | + | At the age of 21, Anne married William Hutchinson, a prosperous cloth merchant, and the couple returned to Alford. The Hutchinson family considered themselves to be part of the [[Puritan]] movement, and in particular, they followed the teachings of the Reverend [[John Cotton]], their religious mentor. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Puritans in England grew increasingly restive following the so-called [[Elizabethan Settlement]], which sought to accommodate differences between Anglican and other Protestant, specifically Puritan faiths. Puritans objected to many of the rituals and Roman Catholic associations of the Church of England, and like other non-[[Anglican]] sects, were being forced to pay taxes to the Crown in England. Following the 1620 voyage of English Separatists known as the [[Pilgrims]] to establish a colony in [[Plymouth]], [[Massachusetts]], Puritans began a mass migration to New England, beginning in 1630, to create a polity based on Puritan beliefs. [[John Cotton]] was relocated to the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts Bay in 1634; the Hutchinsons soon followed with their fifteen children, setting sail on the ''Griffin''. They lost a total of four children in early childhood, one of whom was born in America. | |

| − | + | ==Controversy and trial== | |

| + | A trusted midwife, housewife, and mother, Hutchinson started a weekly women's group that met in her home and discussed the previous Sunday's sermons. In time, Hutchinson began to share her divergent theological opinions, stressing personal intuition over ritual beliefs and practices. Charismatic, articulate, and learned in theology, Hutchinson claimed that holiness came from inner experience of the Holy Spirit. Hutchinson drew friends and neighbors and at some point began more controversial critiques on teachings from the pulpit of the established religious hierarchy, specifically the Reverend John Wilson. As word of her teachings spread, she gained new followers, among them men like [[Henry Vane the Younger|Sir Henry Vane]], who would become the governor of the colony in 1636. Contemporary reports suggest that upwards of eighty people attended her home Bible study sessions. Officially sanctioned sermons may or may not have had more regular attendance. Peters, Vane, and John Cotton may have attempted, according to some historical accounts, to have Reverend Wilson replaced with Anne's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright. | ||

| − | + | In 1637, Vane lost the governorship to [[John Winthrop]], who did not share Vane's opinion of Hutchinson and instead considered her a threat. Hutchinson publicly justified her comments on pulpit teachings and contemporary religious mores as being authorized by "an inner spiritual truth." Governor Winthrop and the established religious hierarchy considered her comments to be heretical, and unfounded criticism of the clergy from an unauthorized source. | |

| − | + | In November 1637, Hutchinson was put on trial before the Massachusetts Bay General Court, presided over by Winthrop, on charges of heresy and "traducing the ministers." Winthrop described her described her as "an American [[Jezebel]], who had gone a-whoring from God" and claimed the meetings were "a thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God, nor fitting for your sex."<ref>''Anne Hutchinson Website,'' [http://www.annehutchinson.com/anne_hutchinson_biography_001.htm Anne Hutchinson.] Retrieved January 18, 2007. </ref> | |

| − | During her trial, which she walked to while being five months pregnant, Hutchinson | + | During her trial, which she walked to while being five months pregnant, Hutchinson answered the accusations with learning and composure, but provocatively chose to assert her personal closeness with God. She claimed that God gave her direct personal revelations, a statement unusual enough at the time to make even John Cotton, her longtime supporter, question her soundness. |

| − | |||

| − | Hutchinson | + | Hutchinson remained combative during the trial. "Therefore, take heed," she warned her interrogators. "For I know that for this that you goe about to doe unto me. God will ruin you and your posterity, and this whole State." Winthrop claimed that "the revelation she brings forth is delusion," and the court accordingly voted to banish her from the colony "as being a woman not fit for our society."<ref>Paul P. Reuben, [http://www.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap1/hutchinson.html#bio Perspectives in American Literature: Anne Hutchinson.] Retrieved December 24, 2008.</ref> |

| − | + | Hutchinson was help under house arrest until a church trial in March 1638. Her former mentor John Cotton now cautioned her sons and sons-in-law against "hindering" the work of God by speaking on her behalf, telling the women of the congregation to be careful, "for you see she is but a woman and many unsound and dangerous Principles are held by her" and attacking her meetings as a "promiscuous and filthie coming together of men and women without Distinction of Relation of Marriage." Then Reverend Wilson delivered her excommunication. "I doe cast you out and in the name of Christ I doe deliver you up to Satan, that you may learne no more to blaspheme, to seduce, and to lye." | |

| − | + | "The Lord judgeth not as man judgeth," she retorted. "Better to be cast out of the church than to deny Christ."<ref>Ibid.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | == Exile and final days == |

| + | Hutchinson with her husband, 13 children, and 60 followers settled on the island of Aquidneck (Peaceable Island), now part of Rhode Island on land purchased from the Narragansett chief Miantonomah. In March 1638 the group of banished dissenters founded the town of Pocasset, renamed Portsmouth in 1639. Gathered on March 7, 1638, the group founded Rhode Island's first civil government, agreeing to the following Compact: <blockquote>We whose names are underwritten do here solemnly in the presence of Jehovah incorporate ourselves into a Bodie Politick and as he shall help, will submit our person, lives and estates unto our Lord Jesus Christ, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords and all those perfect and most absolute laws of his given us in his holy word of truth, to be guided and judged thereby.<ref>Sam Behling, [http://www.rootsweb.com/~nwa/ah.html Anne Marbury Hutchinson,] ''Rootsweb.'' Retrieved January 18, 2007.</ref> </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | After her husband's death in 1642, Hutchinson took her children, except for five of the eldest, to the Dutch colony of New York. A few months later, fifteen Dutchmen were killed in a battle between Mahicans and the Mohawks. In August 1643, the Hutchinson house was raided as an act of reprisal, and Anne and her five youngest children were slaughtered. Only one young daughter who was present, Susanna, who was taken captive, survived and was ransomed back after four years. Her elder children, Edward, Richard, Samuel, Faith, and Bridget, were not present during the slaying, most of whom left numerous descendants. | |

| + | ==Hutchinson's religious beliefs== | ||

| + | <blockquote>As I understand it, laws, commands, rules and edicts are for those who have not the light which makes plain the pathway. He who has God's grace in his heart cannot go astray.<ref>Sam Behling, [http://www.rootsweb.com/~nwa/ah.html Anne Marbury Hutchinson,] ''Rootsweb.'' Retrieved January 18, 2007. </ref> </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hutchinson believed that the Puritan colony had begun to practice a "Covenant of Works" rather than of grace. Puritan theology already taught a Covenant of Grace, so Hutchinson's objections centered on the concept of sanctification. Although Puritan clergy or laymen could not claim to know who among them were among the elect, it was widely thought that an individual’s life of moral rectitude could provide evidence of salvation. This emphasis on the visible act of leading a righteous life led Hutchinson to accuse the church of preaching a Covenant of Works. Such an allegation would have been incendiary to Puritans, who believed that a Covenant of Works amounted to an impossible burden which could only lead to damnation.<ref>Brooke Schieb, [http://smu.edu/ecenter/discourse/Schieb.htm Revising Anne: A Critical Look at Histories of Hutchinson and the Antinomians.] Retrieved December 26, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Hutchinson also argued that many of the clergy were not among the elect, and entitled to no spiritual authority. She questioned assumptions about the proper role of women in Puritan society and also dismissed the idea of [[Original Sin]], saying that one couldn't look into the eyes of a child and see sin therein. Eventually, she began to attack the clergy openly. | |

| − | + | Challenging the religious and political institutionalism of Puritan society, Hutchinson was charged with the heresy of [[antinomianism]], a belief that those who are saved by grace are not under the authority of moral law. In Hutchinson's case, her rejection of rituals and right conduct as signatures of the elect had political ramifications in the Puritan religious hierarchy. | |

| − | + | A reexamination of Hutchinson's 1637 "Immediate Revelation" confession, particularly its biblical allusions, provides a deeper understanding of her position and the reactions of the Massachusetts General Court. Rather than a literal revelation in the form of unmediated divine communication, the confession suggests that Hutchinson experienced her revelations through a form of Biblical divination. The Biblical references in her confession, which contain a [[prophecy]] of catastrophe and redemption, confirm the court's belief that she had transgressed the authority of the colony's ministers. These references also reveal an irreconcilable conflict over theological issues of revelation, miracles, and scripture.<ref>Michael G.Ditmore, "A Prophetess in Her Own Country: an Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson's 'Immediate Revelation,'" ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 2000 57(2): 349-392.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Modern interpretations == | |

| + | Upheld equally as a symbol of [[religious freedom]], liberal thinking and [[feminism]], Anne Hutchinson has been a contentious figure in American history, in turn lionized, mythologized, and demonized. Some historians have argued that Hutchinson suffered more because of her growing influence than her radical teachings. Other have suggested that she fell victim to contemporary mores surrounding the role of women in Puritan society. Hutchinson, according to numerous reports, spoke her mind freely within the context of a male hierarchy unaccustomed to outspoken women. In addition, she welcomed men into her home, an unusual act in a Puritan society. It may also be noteworthy that Hutchinson shared the profession—midwifery—that would become a pivotal attribute of the women accused in the [[Salem witch trials]] of 1692, forty years after her death. | ||

| − | + | Another suggestion is that Hutchinson doomed herself by engaging in political maneuvering surrounding the leadership of her church, and therefore of the local colonial government. She found herself on the losing side of a political battle that continued long after the election was won. | |

| − | + | ==Influence and legacy== | |

| + | Some literary critics trace the character of Hester Prynne in [[Nathaniel Hawthorne]]'s ''The Scarlet Letter'' to Hutchinson and her prosecution in the [[Massachusetts Bay Colony]]. Prynne, like Hutchinson, challenged the religious orthodoxy of Puritan New England and was punished as much for violating the mores of the society as for her intransigence before the political and religious authorities. It has been noted that, in the novel, the rose bush supposedly came up from the foot of Anne Hutchinson outside of the prison. | ||

| − | + | In southern [[New York]] State, the [[Hutchinson River]], one of the very few rivers named after a woman, and the [[Hutchinson River Parkway]] are her most prominent namesakes. Elementary schools, such as in the town of Portsmouth, [[Rhode Island]], and in the Westchester County, New York towns of Pelham, and Eastchester are other examples. | |

| − | + | A statue of Hutchinson stands in front of the State House in Boston, [[Massachusetts]]. It was erected in 1922. The inscription on the statue reads: | |

| + | "In memory of Anne Marbury Hutchinson Baptized at Alford Lincolnshire England 20-July 1595 Killed by the Indians At East Chester New York 1643 Courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration." | ||

| − | + | The site of Anne's house and the scene of her murder is in what is now Pelham Bay Park, within the limits of [[New York City]], less than a dozen miles from the City Hall. Not far from it, beside the road, is a large glacial boulder, popularly called Split Rock. In 1911, a bronze tablet to the memory of Mrs. Hutchinson was placed on Split Rock by the ''Society of Colonial Dames of the State of New York,'' who recognized that the resting place of this most noted woman of her time was well worthy of such a memorial. The tablet bears the following inscription: | |

| + | <blockquote>ANNE HUTCHINSON—Banished From the Massachusetts Bay Colony In 1638 Because of Her Devotion to Religious Liberty | ||

| + | :This Courageous Woman | ||

| + | :Sought Freedom From Persecution | ||

| + | :In New Netherland | ||

| + | :Near This Rock in 1643 She and Her Household | ||

| + | :Were Massacred by Indians | ||

| + | :This Table is placed here by the | ||

| + | :Colonial Dames of the State of New York | ||

| + | :Anno Domini MCMXI | ||

| + | :Virtutes Majorum Fillae Conservant</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1987, Massachusetts Governor [[Michael Dukakis]] pardoned Anne Hutchinson, in order to revoke the order of banishment by Governor Endicott, 350 years earlier. | ||

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | + | == References == | |

| − | + | * Battis, Emery. ''Saints and Sectaries; Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.'' Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1962. | |

| − | + | * Ditmore, Michael G. "A Prophetess in Her Own Country: an Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson's 'Immediate Revelation.'" ''William and Mary Quarterly.'' 2000 57(2): 349-392. | |

| − | + | * Gura, Philip F. ''A Glimpse of Sion's Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England, 1620-1660.'' Middleton, CT: Wesleyan U. Press, 1984. ISBN 0819550957. | |

| − | + | * Lang, Amy Schrager. ''Prophetic Woman: Anne Hutchinson and the Problem of Dissent in the Literature of New England.'' Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0520055985. | |

| + | * LaPlante, Eve. ''American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, The Woman Who Defied the Puritans.'' San Francisco: Harper Press, 2004. ISBN 0060562331. | ||

| + | * Morgan, Edmund S. “The Case Against Anne Hutchinson.” ''New England Quarterly'' 10 (1937): 635-649. | ||

| + | * Richardson, Douglas. ''Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families.'' Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004. ISBN 0806317507. | ||

| + | * Williams, Selma R. ''Divine Rebel: The Life of Anne Marbury Hutchinson.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981. | ||

| + | * Winship, Michael P. ''The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson: Puritans Divided.'' Lawrence, KS: Univ. of Kansas Press, 2005. ISBN 070061379X. | ||

| + | * Winship, Michael P. ''Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636-1641.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002. ISBN 1400814839. | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved July 27, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Michael P. Winship, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14280 ‘Hutchinson , Anne (bap. 1591, d. 1643)’], ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. | |

| − | + | * Rogers, Jay, [http://www.forerunner.com/forerunner/X0193_Anne_Hutchinson.html America's Christian Leaders: Anne Hutchinson] ''The Forerunner'' | |

| − | * Michael P. Winship, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14280 ‘Hutchinson , Anne (bap. 1591, d. 1643)’], ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Biography]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Religion]] |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{credits|96057926}} |

Latest revision as of 06:54, 28 July 2023

Anne Marbury Hutchinson (July 17, 1591 - August 20, 1643) was a leading religious dissenter and nonconforming critic of the Puritan leadership of Massachusetts Bay colony. The daughter of a preacher who had been jailed several times in England for subversive teaching, Hutchinson gathered a group of followers, first to discuss recent sermons but later challenging the religious authority of the colony's Puritan leadership. Claiming that salvation was exclusively the work of inner grace, Hutchinson disparaged the visible acts of moral conduct central to Puritan life as unnecessary to salvation. She was charged with the heresy of antinomianism and eventually banished from the colony with a group of her supporters.

They first settled the island of Aquidneck, which is now part of Rhode Island. Following her husband's death in 1642, Hutchinson and her six youngest children settled in what is now the Pelham Bay section of the Bronx, in New York City. Like many settlers in the area, her family was caught in the middle of bloody reprisals which characterized the conflict between the Dutch and Indian tribes over the territory. She and five of those children were killed there in an attack by members of a Native Algonquian tribe in August 1643.

Anne Hutchinson is often seen as an early American feminist who challenged a religious, male-dominated hierarchy based on an inner prompting. Her emphasis on grace over "works," while not inconsistent with Puritan theology, was interpreted as radical and divisive, partly because of her sharp criticisms of the colony's leadership and partly because women had subservient roles in the church and secular government in Puritan New England.

Early years and emigration to America

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury on July 17, 1591, in Alford, Lincolnshire, England. She was the eldest daughter of Francis Marbury (1555-1611), a clergyman educated at Cambridge and Puritan reformer, and Bridget Dryden (1563-1645). In 1605, she moved with her family from Alford to London.

Anne's father observed a lack of competency among many of the ministers within the Church of England and concluded that they had not attained their positions through proper training, but for political reasons. Openly deploring this, he was eventually arrested for subversive activity, and spent a year in jail. This did not deter him, as he continued to speak out and continued to be arrested.

Anne, likely as a consequence, developed an interest in religion and theology at a very young age. It seemed she inherited her father's ideals and assertiveness, and wasn't afraid of questioning the principles of faith and the authority of the Church, as she would demonstrate in her later years.[1]

At the age of 21, Anne married William Hutchinson, a prosperous cloth merchant, and the couple returned to Alford. The Hutchinson family considered themselves to be part of the Puritan movement, and in particular, they followed the teachings of the Reverend John Cotton, their religious mentor.

Puritans in England grew increasingly restive following the so-called Elizabethan Settlement, which sought to accommodate differences between Anglican and other Protestant, specifically Puritan faiths. Puritans objected to many of the rituals and Roman Catholic associations of the Church of England, and like other non-Anglican sects, were being forced to pay taxes to the Crown in England. Following the 1620 voyage of English Separatists known as the Pilgrims to establish a colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts, Puritans began a mass migration to New England, beginning in 1630, to create a polity based on Puritan beliefs. John Cotton was relocated to the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts Bay in 1634; the Hutchinsons soon followed with their fifteen children, setting sail on the Griffin. They lost a total of four children in early childhood, one of whom was born in America.

Controversy and trial

A trusted midwife, housewife, and mother, Hutchinson started a weekly women's group that met in her home and discussed the previous Sunday's sermons. In time, Hutchinson began to share her divergent theological opinions, stressing personal intuition over ritual beliefs and practices. Charismatic, articulate, and learned in theology, Hutchinson claimed that holiness came from inner experience of the Holy Spirit. Hutchinson drew friends and neighbors and at some point began more controversial critiques on teachings from the pulpit of the established religious hierarchy, specifically the Reverend John Wilson. As word of her teachings spread, she gained new followers, among them men like Sir Henry Vane, who would become the governor of the colony in 1636. Contemporary reports suggest that upwards of eighty people attended her home Bible study sessions. Officially sanctioned sermons may or may not have had more regular attendance. Peters, Vane, and John Cotton may have attempted, according to some historical accounts, to have Reverend Wilson replaced with Anne's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright.

In 1637, Vane lost the governorship to John Winthrop, who did not share Vane's opinion of Hutchinson and instead considered her a threat. Hutchinson publicly justified her comments on pulpit teachings and contemporary religious mores as being authorized by "an inner spiritual truth." Governor Winthrop and the established religious hierarchy considered her comments to be heretical, and unfounded criticism of the clergy from an unauthorized source.

In November 1637, Hutchinson was put on trial before the Massachusetts Bay General Court, presided over by Winthrop, on charges of heresy and "traducing the ministers." Winthrop described her described her as "an American Jezebel, who had gone a-whoring from God" and claimed the meetings were "a thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God, nor fitting for your sex."[2]

During her trial, which she walked to while being five months pregnant, Hutchinson answered the accusations with learning and composure, but provocatively chose to assert her personal closeness with God. She claimed that God gave her direct personal revelations, a statement unusual enough at the time to make even John Cotton, her longtime supporter, question her soundness.

Hutchinson remained combative during the trial. "Therefore, take heed," she warned her interrogators. "For I know that for this that you goe about to doe unto me. God will ruin you and your posterity, and this whole State." Winthrop claimed that "the revelation she brings forth is delusion," and the court accordingly voted to banish her from the colony "as being a woman not fit for our society."[3]

Hutchinson was help under house arrest until a church trial in March 1638. Her former mentor John Cotton now cautioned her sons and sons-in-law against "hindering" the work of God by speaking on her behalf, telling the women of the congregation to be careful, "for you see she is but a woman and many unsound and dangerous Principles are held by her" and attacking her meetings as a "promiscuous and filthie coming together of men and women without Distinction of Relation of Marriage." Then Reverend Wilson delivered her excommunication. "I doe cast you out and in the name of Christ I doe deliver you up to Satan, that you may learne no more to blaspheme, to seduce, and to lye."

"The Lord judgeth not as man judgeth," she retorted. "Better to be cast out of the church than to deny Christ."[4]

Exile and final days

Hutchinson with her husband, 13 children, and 60 followers settled on the island of Aquidneck (Peaceable Island), now part of Rhode Island on land purchased from the Narragansett chief Miantonomah. In March 1638 the group of banished dissenters founded the town of Pocasset, renamed Portsmouth in 1639. Gathered on March 7, 1638, the group founded Rhode Island's first civil government, agreeing to the following Compact:

We whose names are underwritten do here solemnly in the presence of Jehovah incorporate ourselves into a Bodie Politick and as he shall help, will submit our person, lives and estates unto our Lord Jesus Christ, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords and all those perfect and most absolute laws of his given us in his holy word of truth, to be guided and judged thereby.[5]

After her husband's death in 1642, Hutchinson took her children, except for five of the eldest, to the Dutch colony of New York. A few months later, fifteen Dutchmen were killed in a battle between Mahicans and the Mohawks. In August 1643, the Hutchinson house was raided as an act of reprisal, and Anne and her five youngest children were slaughtered. Only one young daughter who was present, Susanna, who was taken captive, survived and was ransomed back after four years. Her elder children, Edward, Richard, Samuel, Faith, and Bridget, were not present during the slaying, most of whom left numerous descendants.

Hutchinson's religious beliefs

As I understand it, laws, commands, rules and edicts are for those who have not the light which makes plain the pathway. He who has God's grace in his heart cannot go astray.[6]

Hutchinson believed that the Puritan colony had begun to practice a "Covenant of Works" rather than of grace. Puritan theology already taught a Covenant of Grace, so Hutchinson's objections centered on the concept of sanctification. Although Puritan clergy or laymen could not claim to know who among them were among the elect, it was widely thought that an individual’s life of moral rectitude could provide evidence of salvation. This emphasis on the visible act of leading a righteous life led Hutchinson to accuse the church of preaching a Covenant of Works. Such an allegation would have been incendiary to Puritans, who believed that a Covenant of Works amounted to an impossible burden which could only lead to damnation.[7]

Hutchinson also argued that many of the clergy were not among the elect, and entitled to no spiritual authority. She questioned assumptions about the proper role of women in Puritan society and also dismissed the idea of Original Sin, saying that one couldn't look into the eyes of a child and see sin therein. Eventually, she began to attack the clergy openly.

Challenging the religious and political institutionalism of Puritan society, Hutchinson was charged with the heresy of antinomianism, a belief that those who are saved by grace are not under the authority of moral law. In Hutchinson's case, her rejection of rituals and right conduct as signatures of the elect had political ramifications in the Puritan religious hierarchy.

A reexamination of Hutchinson's 1637 "Immediate Revelation" confession, particularly its biblical allusions, provides a deeper understanding of her position and the reactions of the Massachusetts General Court. Rather than a literal revelation in the form of unmediated divine communication, the confession suggests that Hutchinson experienced her revelations through a form of Biblical divination. The Biblical references in her confession, which contain a prophecy of catastrophe and redemption, confirm the court's belief that she had transgressed the authority of the colony's ministers. These references also reveal an irreconcilable conflict over theological issues of revelation, miracles, and scripture.[8]

Modern interpretations

Upheld equally as a symbol of religious freedom, liberal thinking and feminism, Anne Hutchinson has been a contentious figure in American history, in turn lionized, mythologized, and demonized. Some historians have argued that Hutchinson suffered more because of her growing influence than her radical teachings. Other have suggested that she fell victim to contemporary mores surrounding the role of women in Puritan society. Hutchinson, according to numerous reports, spoke her mind freely within the context of a male hierarchy unaccustomed to outspoken women. In addition, she welcomed men into her home, an unusual act in a Puritan society. It may also be noteworthy that Hutchinson shared the profession—midwifery—that would become a pivotal attribute of the women accused in the Salem witch trials of 1692, forty years after her death.

Another suggestion is that Hutchinson doomed herself by engaging in political maneuvering surrounding the leadership of her church, and therefore of the local colonial government. She found herself on the losing side of a political battle that continued long after the election was won.

Influence and legacy

Some literary critics trace the character of Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter to Hutchinson and her prosecution in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Prynne, like Hutchinson, challenged the religious orthodoxy of Puritan New England and was punished as much for violating the mores of the society as for her intransigence before the political and religious authorities. It has been noted that, in the novel, the rose bush supposedly came up from the foot of Anne Hutchinson outside of the prison.

In southern New York State, the Hutchinson River, one of the very few rivers named after a woman, and the Hutchinson River Parkway are her most prominent namesakes. Elementary schools, such as in the town of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and in the Westchester County, New York towns of Pelham, and Eastchester are other examples.

A statue of Hutchinson stands in front of the State House in Boston, Massachusetts. It was erected in 1922. The inscription on the statue reads: "In memory of Anne Marbury Hutchinson Baptized at Alford Lincolnshire England 20-July 1595 Killed by the Indians At East Chester New York 1643 Courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration."

The site of Anne's house and the scene of her murder is in what is now Pelham Bay Park, within the limits of New York City, less than a dozen miles from the City Hall. Not far from it, beside the road, is a large glacial boulder, popularly called Split Rock. In 1911, a bronze tablet to the memory of Mrs. Hutchinson was placed on Split Rock by the Society of Colonial Dames of the State of New York, who recognized that the resting place of this most noted woman of her time was well worthy of such a memorial. The tablet bears the following inscription:

ANNE HUTCHINSON—Banished From the Massachusetts Bay Colony In 1638 Because of Her Devotion to Religious Liberty

- This Courageous Woman

- Sought Freedom From Persecution

- In New Netherland

- Near This Rock in 1643 She and Her Household

- Were Massacred by Indians

- This Table is placed here by the

- Colonial Dames of the State of New York

- Anno Domini MCMXI

- Virtutes Majorum Fillae Conservant

In 1987, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis pardoned Anne Hutchinson, in order to revoke the order of banishment by Governor Endicott, 350 years earlier.

Notes

- ↑ Anne Hutchinson Website, Anne Hutchinson. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Anne Hutchinson Website, Anne Hutchinson. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Paul P. Reuben, Perspectives in American Literature: Anne Hutchinson. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Sam Behling, Anne Marbury Hutchinson, Rootsweb. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Sam Behling, Anne Marbury Hutchinson, Rootsweb. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Brooke Schieb, Revising Anne: A Critical Look at Histories of Hutchinson and the Antinomians. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ Michael G.Ditmore, "A Prophetess in Her Own Country: an Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson's 'Immediate Revelation,'" William and Mary Quarterly 2000 57(2): 349-392.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Battis, Emery. Saints and Sectaries; Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1962.

- Ditmore, Michael G. "A Prophetess in Her Own Country: an Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson's 'Immediate Revelation.'" William and Mary Quarterly. 2000 57(2): 349-392.

- Gura, Philip F. A Glimpse of Sion's Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England, 1620-1660. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan U. Press, 1984. ISBN 0819550957.

- Lang, Amy Schrager. Prophetic Woman: Anne Hutchinson and the Problem of Dissent in the Literature of New England. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0520055985.

- LaPlante, Eve. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, The Woman Who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Press, 2004. ISBN 0060562331.

- Morgan, Edmund S. “The Case Against Anne Hutchinson.” New England Quarterly 10 (1937): 635-649.

- Richardson, Douglas. Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004. ISBN 0806317507.

- Williams, Selma R. Divine Rebel: The Life of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981.

- Winship, Michael P. The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson: Puritans Divided. Lawrence, KS: Univ. of Kansas Press, 2005. ISBN 070061379X.

- Winship, Michael P. Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636-1641. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002. ISBN 1400814839.

External links

All links retrieved July 27, 2023.

- Michael P. Winship, ‘Hutchinson , Anne (bap. 1591, d. 1643)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Rogers, Jay, America's Christian Leaders: Anne Hutchinson The Forerunner

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.