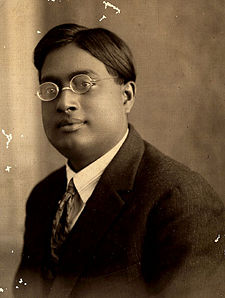

Satyendra Nath Bose

|

Satyendra Nath Bose | |

|---|---|

Satyendra Nath Bose | |

| Born | |

| Died | February 4, 1974 |

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Field | Physics |

| Institutions | Calcutta University University of Dhaka |

| Alma mater | Presidency College |

| Academic advisor | Jagdish Chandra Bose |

| Known for | Bose-Einstein statistics |

| Note that Bose did not have a doctorate, but obtained an MSc in 1915 and therefore did not have a doctoral advisor. However his equivalent mentor was Jagdish Chandra Bose. | |

Satyendra Nath Bose (/sɐθ.jin.ðrɐ nɑθ bos/ Bengali: সত্যেন্দ্র নাথ বসু) (January 1, 1894 – February 4, 1974) was a Bengali Indian physicist, specializing in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose-Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose-Einstein condensate. He is honored as the namesake of the boson.

Although more than one Nobel Prize was awarded for research related to the concepts of the boson, Bose-Einstein statistics and Bose-Einstein condensate — the latest being the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, which was given for advancing the theory of Bose-Einstein condensates, Bose himself was never awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Among his other talents, Bose knew many languages and also could play Esraj (a musical instrument similar to a violin) very well.

In his book, The Scientific Edge, the noted physicist Jayant Narlikar observed:

"S.N. Bose’s work on particle statistics (c. 1922), which clarified the behaviour of photons (the particles of light in an enclosure) and opened the door to new ideas on statistics of Microsystems that obey the rules of quantum theory, was one of the top ten achievements of 20th century Indian science and could be considered in the Nobel Prize class." [1]

Early life and Career

Bose was born in Kolkata (Calcutta), West Bengal, India, the eldest of seven children. His father, Surendranath Bose, worked in the Engineering Department of the East India Railway.

Bose attended Hindu School in Calcutta, and later attended Presidency College, also in Calcutta, earning the highest marks at each institution. He came in contact with brilliant teachers such as Jagadish Chandra Bose (no relation) and Prafulla Chandra Roy who provided inspiration to aim high in life. From 1916 to 1921 he was a lecturer in the physics department of the University of Calcutta. In 1921, he joined the department of Physics of the then recently founded Dacca University (now in Bangladesh and called University of Dhaka), again as a lecturer.

In 1924 Bose wrote a paper deriving Planck's quantum radiation law without any reference to classical physics. After initial setbacks to his efforts to publish, he sent the article directly to Albert Einstein in Germany. Einstein, recognizing the importance of the paper, translated it into German himself and submitted it on Bose's behalf to the prestigious Zeitschrift für Physik. As a result of this recognition, Bose was able to leave India for the first time and spent two years in Europe, during which he worked with Louis de Broglie, Marie Curie, and Einstein.

Bose returned to Dacca in 1926. He became a professor and was made head of the Department of Physics, and continued teaching at Dhaka University until 1945. At that time he returned to Calcutta, and taught at Calcutta University until 1956, when he retired and was made professor emeritus.

The error that wasn't

| Two heads | Two tails | One of each |

There are three outcomes. What is the probability of producing two heads?

While at the University of Dhaka, Bose wrote a short article called Planck's Law and the Hypothesis of Light Quanta, describing the photoelectric effect and based on a lecture he had given on the ultraviolet catastrophe. During this lecture, in which he had intended to show his students that theory predicted outcomes not in accordance with experimental results, Bose made an embarrassing statistical error that gave a prediction that agreed with observations, a contradiction.

| Coin 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Tail | ||

| Coin 2 | Head | HH | HT |

| Tail | TH | TT | |

Since the coins are distinct, there are two outcomes which produce a head and a tail. The probability of two heads is one-fourth.

The error was a simple mistake that would appear obviously wrong to anyone with a basic understanding of statistics, and similar to arguing that flipping two fair coins will produce two heads one-third of the time. However, it produced correct results, and Bose realized it might not be a mistake at all. He for the first time held that the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution would not be true for microscopic particles where fluctuations due to Heisenberg's uncertainty principle will be significant. Thus he stressed in the probability of finding particles in the phase space each having volumes h3 and discarding the distinct position and momentum of the particles.

Physics journals refused to publish Bose's paper. It was their contention that he had presented to them a simple mistake, and Bose's findings were ignored. Discouraged, he wrote to Albert Einstein, who immediately agreed with him. Physicists stopped laughing when Einstein sent Zeitschrift für Physik his own paper to accompany Bose's, which were published in 1924. Bose had earlier translated Einstein's theory of General Relativity from German to English. It is said that Bose had taken Albert Einstein as his Guru (mentor).

Because photons are indistinguishable from each other, one cannot treat any two photons having equal energy as being different from each other. By analogy, if the coins in the above example behaved like photons and other bosons, the probability of producing two heads would indeed be one-third (tail-head = head-tail). Bose's "error" is now called Bose-Einstein statistics.

Einstein adopted the idea and extended it to atoms. This led to the prediction of the existence of phenomena which became known as Bose-Einstein condensate, a dense collection of bosons (which are particles with integer spin, named after Bose), which was proven to exist by experiment in 1995.

Later work

Bose's ideas were afterward well received in the world of physics, and he was granted leave from the University of Dhaka to travel to Europe in 1924. He spent a year in France and worked with Marie Curie, and met several other well-known scientists. He then spent another year abroad, working with Einstein in Berlin. Upon his return to Dhaka, he was made a professor in 1926. He did not have a doctorate, and so ordinarily he would not be qualified for the post, but Einstein recommended him. His work ranged from X-ray crystallography to grand unified theories. He together with Meghnad Saha published an equation of state for real gases.

Apart from physics he did some research in biochemistry and literature (Bengali, English). He made deep studies in chemistry, geology, zoology, anthropology, engineering and other sciences. Being of Bengali origin, he devoted a lot of time to promoting Bengali as a teaching language, transliterating scientific papers into it, and promoting the development of the region.

In 1944, Bose was elected General President of the Indian Science Congress.

In 1958, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Anecdote

Once the great scientist, Niels Bohr, was delivering a lecture. Bose presided. At one stage the lecturer had some difficulty in explaining a point. He had been writing on the blackboard; he stopped and, turning to Bose, said, "Can Professor Bose help me?" All the while Satyendranath had been sitting with his eyes shut. The audience could not help smiling at Professor Bohr's words. But to their great surprise, Bose opened his eyes; in an instant he solved the lecturer's difficulty. Then he sat down and once again closed his eyes! — biography at Calcuttaweb

See also

- Bose-Einstein condensate

- Jagdish Chandra Bose

Notes

- ↑ The Scientific Edge by Jayant V. Narlikar, Penguin Books, 2003, page 127. The work of other twentieth-century Indian scientists who Narlikar considered to be of Nobel Prize class were Srinivasa Ramanujan, Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, and Meghnad Saha.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- S.N. Bose. "Plancks Gesetz und Lichtquantenhypothese," Zeitschrift für Physik 26:178-181 (1924). (The German translation of Bose's paper on Planck's law)

- Abraham Pais. "Subtle is the Lord...": The Science and Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. (pp. 423-434). ISBN 0-19-853907-X.

- "Heat and thermodynamics" Saha and Srivasthava.

External links

- Scienceworld's biography of Satyendra Nath Bose

- Satyendra Nath Bose (biography at Calcuttaweb)

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Satyendra Nath Bose at the MacTutor archive

- The Indian Particle Man (audio biography at BBC Radio 4)

- Bosons - The Birds That Flock and Sing Together (biography of Bose and Bose-Einstein Condensation)

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Bose, Satyendra Nath |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 1,1894 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Calcutta, India |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 4, 1974 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Calcutta, India |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.