Difference between revisions of "Great Chain of Being" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (imported from wiki) |

(rewrote article) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

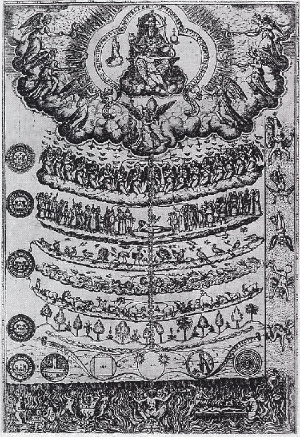

[[Image:Great_Chain_of_Being_2.png|thumb|right|[[1579]] drawing of the great chain of being from [[Didacus Valades]], ''Rhetorica Christiana'']] | [[Image:Great_Chain_of_Being_2.png|thumb|right|[[1579]] drawing of the great chain of being from [[Didacus Valades]], ''Rhetorica Christiana'']] | ||

| − | The | + | The great chain of being' or ''scala naturæ'' is a classical conception of the metaphysical order of the universe, whose chief characteristic is a strict hierarchical system of being. This chain is composed of a number of hierarchal links, from the most basic beings up to the very highest and most perfect Being. Although this notion was viewed in various ways from antiquity and throughout the medieval period, its philosophical formulation can perhaps best be seen beginning with Aristotle, moving through the Neoplatonists, and culminating in the theological vision of the scholastics. Although many modern philosophers abandon the classical view, some alternate versions of the Great Chain of Being can be seen in the metaphysical rationalists of the 17th and 18th century. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Aristotle == | |

| + | Although it was the Neoplatonists who fully developed the notion of a unified hierarchy of Being, its roots can be found in both Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle, in particular, viewed the universe as being eternal and made up of a number of distinct forms of being. On the lowest rung were lifeless “artifacts” such as rocks, whose material composition was held together by physical forces. To break a piece of rock in two caused no substantial change, since the rock had no [[essence]] or [[soul]]. In classical philosophy soul (anima) was attributed not only to human beings, but to all living things. Soul was defined as the inner organic principle which animates the being such that it is alive. Thus, all living beings have essences or [[substantial forms]], which determine the kind of attributes or powers that that particular being possesses. For Aristotle there was a kind of hierarchy of souls, which was classified by the soul’s specific powers. | ||

| − | + | First, any being with life possess the powers to grow and reproduce. This includes all plant life, such as trees, grass, and flowers. Next, there is the sensible soul or animal life. Although animal life itself can be broken up into various classes depending on the specific attributes, Aristotle located a number of powers which the higher animals all possess. These include the powers of the lower forms of life (growth and reproduction) along with higher ones (sense, movement, and memory). Above the sensitive soul is the rational soul, which defines the human being. Along with all the powers of both plant and animal life, the human being possesses the power of reason and all the functions of rationality. | |

| − | + | Again, in Aristotle’s [[cosmology]] the universe was eternal. For this reason he considered the celestial beings (sun, planets, stars, etc.) as also being eternal. These celestial beings were considered not only eternal but godly and so their circular course or movement was divine. Finally, in his Metaphysics Aristotle offers his famous argument for the existence of the Prime Mover, which is the ultimate source and principle of all movement throughout the universe. Although the scholastics will later translate Aristotle’s “First Mover” into a personal God, Aristotle’s understanding of this divine First Mover remains ambiguous. | |

| + | |||

| + | == Neoplatonism== | ||

| + | The Neoplatonists, such as [[Plotinus]] (205-270), took Aristotle’s hierarchy of distinct beings and “spiritualized” it into a quasi-mystical unity inspired by Plato. While the basic hierarchal structure of Aristotle remained the same, the highest “forms” were transformed into purely spiritual or immaterial beings. Plato, in his famous Theory of the Forms, had thought of Ideas as immutable or unchangeable beings in which material beings on earth participated. For example, all individual dogs participated in the one eternal Idea of Dog (or Dogness) which exists in a higher, immaterial realm. Also, in his famous Analogy of the Sun Plato speaks of the Good which is “beyond all being.” The Neoplatonists develop these notions in such a way that the degree of goodness a thing possesses depends upon its degree of being, that is, the extent to which a being participates in the One or Good. The Great Chain of Being, then, is seen as a chain of [[emanation]]. The One is at the top and so all being flows downward from the One. Below the One, then, are the spiritual beings of Ideas, rational human beings, sensible animals, living plants, and finally inanimate things (which merely exist). Human beings hold a particularly interesting place in this perspective since they exist at once in both the immaterial and material realms. The more humans turn downward and absorb themselves in material things, the more they turn away from the good and become evil. In contrast, the more humans turn upward to the intelligible realm and the Good, the more being or goodness they possess. Moreover, in this conception pure evil does not exist. For evil, strictly speaking, is not a being or positive force but rather a privation or lack of being. | ||

| − | + | ==Scholasticism == | |

| + | [[St. Augustine]] borrowed the basic scheme developed by Neoplatonism and theologized it into a Christian understanding. While the lower, material realm remained the same, the higher intelligible sphere and the notion of the Good shifted in important ways. First, the Good or One became the personal and triune God of Christianity. Below God there were the higher, spiritual beings called angels. Finally, the Ideas or Forms of the intelligible realm remained in Augustine, but now they were considered to be Divine Ideas or [[Universals]], which existed in the mind of God. | ||

| − | + | The basic scheme of the Great Chain of Being endured throughout the medieval period, though disputes persisted regarding the exact nature of Universals and to what extent human beings could participate or know the thoughts of God. Moreover, in many of the more sophisticated, scholastic thinkers, the classification of earthly beings was subdivided into more distinct [[species]]. Also, the great 13th century philosopher and theologian [[St. Thomas Aquinas]] (1225?-1274), determined that the angels could not be members of the same species, the way individual humans beings are of the same species. The reason is that for Aquinas matter is what individuates all beings of the same species; angels, however, are immaterial; therefore, in order for angels to be separate and individual they must each be their own species, or “one of a kind”. | |

| + | |||

| + | Also, in the scholastic understanding of the Great Chain of Being, the place of human beings takes on a greater moral significance. Since humans participate in both the earthly and spiritual realms, their movement through life is considered to be a journey toward God. The temptations of the earthly or mortal flesh lead to evil, whereas the contemplation of things divine lead to transcendence of the spirit. Thus, the struggle between flesh and spirit becomes a specifically moral one. The way of the spirit lifts one up toward God, while the desires of the flesh sink one into the privations of evil. | ||

| − | + | In medieval society, one sees how the Great Chain extended into the political sphere as well. For here too there was a distinct separation or hierarchy between human beings. The king reigned supreme at the top, and below him were the aristocratic lords. At the bottom were the serfs. Solidifying the king's position atop of humanity's social order was the doctrine of the [[divine right of kings]]. Likewise, in the family the father was head of the household and below him was his wife, then their children. The children were even often subdivided so that the sons were considered to be one rung above the daughters. | |

| − | + | ==Modern Rationalism== | |

| + | The emergence of modern science and the [[Copernican Revolution]] is often considered to have dismantled The Great Chain of Being as a worldview. Nonetheless, certain rational metaphysicians, such as [[Rene Descartes]] (1596-1650), [[Baruch Spinoza]] (1632-1677) and G. W. von Leibniz (1646-1716), created alternate versions of the Great Chain. The distinguishing feature is that they all tried to devise rational systems which explain God or Being as the ultimate Perfection such that all other forms of being were lesser or imperfect modes or derivatives of the perfect Being. Most of these thinkers offer proofs for the existence of this highest Being and then from this necessary principle deduce all other beings. | ||

| − | The | + | ==Primary Sources== |

| + | * Aristotle. The Basic Works of Aristotle. Translated by Richard McKeon. Random House, 1941. ISBN 0375757996. | ||

| + | * Descartes, Rene. Philosophical Essays, Translated by Laurence Lafleur. Bobbs-Merrill, 1964. ISBN 0872205029. | ||

| + | * Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. Discourse on Metaphysics and Other Essays. Translated by Daniel Garber and Roger Ariew. Hackett, 1991. ISBN 0872201325. | ||

| + | * Plato, Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992. ISBN 0872201368. | ||

| + | * Spinoza, Baruch. Ethics, Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, and Selected Letters. Translated by Samuel Shirley and Seymour Feldman. Hackett, 1992. ISBN 0872201309. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Secondary Sources== |

| − | * | + | *Lovejoy, Arthur Oncken. ''The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea,'' (1936) ISBN 0-674-36153-9 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/DHI/dhi.cgi?id=dv1-45 ''Dictionary of the History of Ideas''] – Chain of Being | * [http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/DHI/dhi.cgi?id=dv1-45 ''Dictionary of the History of Ideas''] – Chain of Being | ||

* [http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/courses/re/chain.htm The Great Chain of Being reflected in the work of Descartes, Spinoza & Leibniz] Peter Suber, [[Earlham College]], [[Indiana]] | * [http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/courses/re/chain.htm The Great Chain of Being reflected in the work of Descartes, Spinoza & Leibniz] Peter Suber, [[Earlham College]], [[Indiana]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|88363907}} | {{credit|88363907}} | ||

Revision as of 19:54, 17 May 2007

The great chain of being' or scala naturæ is a classical conception of the metaphysical order of the universe, whose chief characteristic is a strict hierarchical system of being. This chain is composed of a number of hierarchal links, from the most basic beings up to the very highest and most perfect Being. Although this notion was viewed in various ways from antiquity and throughout the medieval period, its philosophical formulation can perhaps best be seen beginning with Aristotle, moving through the Neoplatonists, and culminating in the theological vision of the scholastics. Although many modern philosophers abandon the classical view, some alternate versions of the Great Chain of Being can be seen in the metaphysical rationalists of the 17th and 18th century.

Aristotle

Although it was the Neoplatonists who fully developed the notion of a unified hierarchy of Being, its roots can be found in both Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle, in particular, viewed the universe as being eternal and made up of a number of distinct forms of being. On the lowest rung were lifeless “artifacts” such as rocks, whose material composition was held together by physical forces. To break a piece of rock in two caused no substantial change, since the rock had no essence or soul. In classical philosophy soul (anima) was attributed not only to human beings, but to all living things. Soul was defined as the inner organic principle which animates the being such that it is alive. Thus, all living beings have essences or substantial forms, which determine the kind of attributes or powers that that particular being possesses. For Aristotle there was a kind of hierarchy of souls, which was classified by the soul’s specific powers.

First, any being with life possess the powers to grow and reproduce. This includes all plant life, such as trees, grass, and flowers. Next, there is the sensible soul or animal life. Although animal life itself can be broken up into various classes depending on the specific attributes, Aristotle located a number of powers which the higher animals all possess. These include the powers of the lower forms of life (growth and reproduction) along with higher ones (sense, movement, and memory). Above the sensitive soul is the rational soul, which defines the human being. Along with all the powers of both plant and animal life, the human being possesses the power of reason and all the functions of rationality.

Again, in Aristotle’s cosmology the universe was eternal. For this reason he considered the celestial beings (sun, planets, stars, etc.) as also being eternal. These celestial beings were considered not only eternal but godly and so their circular course or movement was divine. Finally, in his Metaphysics Aristotle offers his famous argument for the existence of the Prime Mover, which is the ultimate source and principle of all movement throughout the universe. Although the scholastics will later translate Aristotle’s “First Mover” into a personal God, Aristotle’s understanding of this divine First Mover remains ambiguous.

Neoplatonism

The Neoplatonists, such as Plotinus (205-270), took Aristotle’s hierarchy of distinct beings and “spiritualized” it into a quasi-mystical unity inspired by Plato. While the basic hierarchal structure of Aristotle remained the same, the highest “forms” were transformed into purely spiritual or immaterial beings. Plato, in his famous Theory of the Forms, had thought of Ideas as immutable or unchangeable beings in which material beings on earth participated. For example, all individual dogs participated in the one eternal Idea of Dog (or Dogness) which exists in a higher, immaterial realm. Also, in his famous Analogy of the Sun Plato speaks of the Good which is “beyond all being.” The Neoplatonists develop these notions in such a way that the degree of goodness a thing possesses depends upon its degree of being, that is, the extent to which a being participates in the One or Good. The Great Chain of Being, then, is seen as a chain of emanation. The One is at the top and so all being flows downward from the One. Below the One, then, are the spiritual beings of Ideas, rational human beings, sensible animals, living plants, and finally inanimate things (which merely exist). Human beings hold a particularly interesting place in this perspective since they exist at once in both the immaterial and material realms. The more humans turn downward and absorb themselves in material things, the more they turn away from the good and become evil. In contrast, the more humans turn upward to the intelligible realm and the Good, the more being or goodness they possess. Moreover, in this conception pure evil does not exist. For evil, strictly speaking, is not a being or positive force but rather a privation or lack of being.

Scholasticism

St. Augustine borrowed the basic scheme developed by Neoplatonism and theologized it into a Christian understanding. While the lower, material realm remained the same, the higher intelligible sphere and the notion of the Good shifted in important ways. First, the Good or One became the personal and triune God of Christianity. Below God there were the higher, spiritual beings called angels. Finally, the Ideas or Forms of the intelligible realm remained in Augustine, but now they were considered to be Divine Ideas or Universals, which existed in the mind of God.

The basic scheme of the Great Chain of Being endured throughout the medieval period, though disputes persisted regarding the exact nature of Universals and to what extent human beings could participate or know the thoughts of God. Moreover, in many of the more sophisticated, scholastic thinkers, the classification of earthly beings was subdivided into more distinct species. Also, the great 13th century philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas (1225?-1274), determined that the angels could not be members of the same species, the way individual humans beings are of the same species. The reason is that for Aquinas matter is what individuates all beings of the same species; angels, however, are immaterial; therefore, in order for angels to be separate and individual they must each be their own species, or “one of a kind”.

Also, in the scholastic understanding of the Great Chain of Being, the place of human beings takes on a greater moral significance. Since humans participate in both the earthly and spiritual realms, their movement through life is considered to be a journey toward God. The temptations of the earthly or mortal flesh lead to evil, whereas the contemplation of things divine lead to transcendence of the spirit. Thus, the struggle between flesh and spirit becomes a specifically moral one. The way of the spirit lifts one up toward God, while the desires of the flesh sink one into the privations of evil.

In medieval society, one sees how the Great Chain extended into the political sphere as well. For here too there was a distinct separation or hierarchy between human beings. The king reigned supreme at the top, and below him were the aristocratic lords. At the bottom were the serfs. Solidifying the king's position atop of humanity's social order was the doctrine of the divine right of kings. Likewise, in the family the father was head of the household and below him was his wife, then their children. The children were even often subdivided so that the sons were considered to be one rung above the daughters.

Modern Rationalism

The emergence of modern science and the Copernican Revolution is often considered to have dismantled The Great Chain of Being as a worldview. Nonetheless, certain rational metaphysicians, such as Rene Descartes (1596-1650), Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) and G. W. von Leibniz (1646-1716), created alternate versions of the Great Chain. The distinguishing feature is that they all tried to devise rational systems which explain God or Being as the ultimate Perfection such that all other forms of being were lesser or imperfect modes or derivatives of the perfect Being. Most of these thinkers offer proofs for the existence of this highest Being and then from this necessary principle deduce all other beings.

Primary Sources

- Aristotle. The Basic Works of Aristotle. Translated by Richard McKeon. Random House, 1941. ISBN 0375757996.

- Descartes, Rene. Philosophical Essays, Translated by Laurence Lafleur. Bobbs-Merrill, 1964. ISBN 0872205029.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. Discourse on Metaphysics and Other Essays. Translated by Daniel Garber and Roger Ariew. Hackett, 1991. ISBN 0872201325.

- Plato, Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992. ISBN 0872201368.

- Spinoza, Baruch. Ethics, Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, and Selected Letters. Translated by Samuel Shirley and Seymour Feldman. Hackett, 1992. ISBN 0872201309.

Secondary Sources

- Lovejoy, Arthur Oncken. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, (1936) ISBN 0-674-36153-9

External links

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas – Chain of Being

- The Great Chain of Being reflected in the work of Descartes, Spinoza & Leibniz Peter Suber, Earlham College, Indiana

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.