Difference between revisions of "Intelligence test" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

Individuals with an unusually low IQ score, varying from about 70 ("Educable Mentally Retarded") to as low as 20 (usually caused by a neurological condition), are considered to have developmental difficulties. However, there is no true IQ-based classification for [[Developmental disability|developmental disabilities]]. | Individuals with an unusually low IQ score, varying from about 70 ("Educable Mentally Retarded") to as low as 20 (usually caused by a neurological condition), are considered to have developmental difficulties. However, there is no true IQ-based classification for [[Developmental disability|developmental disabilities]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Positive correlations with IQ== |

| + | While IQ is sometimes treated as an end unto itself, scholarly work on IQ focuses to a large extent on IQ's [[validity (psychometric)|validity]], that is, the degree to which IQ correlates with outcomes such as job performance, social pathologies, or academic achievement. Different IQ tests differ in their validity for various outcomes. Traditionally, correlation for IQ and outcomes is viewed as a means to also predict performance; however, because IQ is a known [[social]] [[artifact]], readers should distinguish between [[prediction]] in the [[hard sciences]] and the [[social sciences]]. | ||

| − | + | ''Validity'' is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure), and ranges between −1.0 (the score is perfectly wrong in predicting outcome) and 1.0 (the score perfectly predicts the outcome). See [[validity (psychometric)]]. | |

| − | Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between ''[[g (factor)|g]]'' and life outcomes are pervasive, | + | Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates to some degree with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between ''[[g (factor)|g]]'' and life outcomes are pervasive, though IQ does not correlate with subjective self-reports of happiness. IQ and ''g'' correlate highly with school performance and job performance, less so with occupational prestige, moderately with income, and to a small degree with law-abiding behaviour. IQ does not explain the inheritance of economic status and wealth. |

| − | + | === Other tests === | |

| + | One study found a correlation of .82 between ''g'' and [[SAT]] scores.[http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1111%2Fj.0956-797.2004.00687.x] Another correlation of .81 between ''g'' and [[GCSE]] scores.[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6W4M-4JDN6DP-1/2/850d67264b9588a28059387bca359ff7] | ||

| − | + | Correlations between IQ scores (general cognitive ability) and achievement test scores are reported to be .81 by Deary and colleagues, with the percentage of variance accounted for by general cognitive ability ranging "from 58.6% in Mathematics and 48% in English to 18.1% in Art and Design"<ref>Ian J. Deary, Steve Strand, Pauline Smith and Cres Fernandes, Intelligence and educational achievement, Intelligence, Volume 35, Issue 1, January-February 2007, Pages 13-21.</ref> | |

| − | + | === School performance === | |

| + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> Wherever it has been studied, children with high scores on tests of intelligence tend to learn more of what is taught in school than their lower-scoring peers. The correlation between IQ scores and grades is about .50. However, this means that they explain only 25% of the variance. Successful school learning depends on many personal characteristics other than intelligence, such as [[memory]], persistence, interest in school, and willingness to study. | ||

| − | + | Correlations between IQ scores and total years of education are about .55, implying that differences in psychometric intelligence account for about 30% of the outcome variance. Many occupations can only be entered through professional schools which base their admissions at least partly on test scores: the MCAT, the GMAT, the GRE, the DAT, the LSAT, etc. Individual scores on admission-related tests such as these are certainly correlated with scores on tests of intelligence. It is partly because intelligence test scores predict years of education that they also predict occupational status, and income to a smaller extent. | |

| − | + | === Job performance === | |

| − | + | According to Schmidt and Hunter, "for hiring employees without previous experience in the job the most valid predictor of future performance is general mental ability."<ref name="Schmidt98">Schmidt, F. L. and Hunter, J. E. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in psychology: practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 262–274.</ref> The validity depends on the type of job and varies across different studies, ranging from 0.2 to 0.6 <ref name="Hunter84">Hunter, J. E. and Hunter, R. F. (1984). Validity and utility of alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 72–98.</ref>. However IQ mostly correlates with cognitive ability only if IQ scores are below average and this rule has many (about 30 %) exceptions for people with average and higher IQ scores <ref name="DiazAsper1">Diaz-Asper CM, Schretlen DJ, Pearlson GD. How well does IQ predict neuropsychological test performance in normal adults? J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004 Jan;10(1):82-90. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=pubmed&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=14751010&ordinalpos=22&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum PubMed link] </ref>. Also, IQ is related to the "academic tasks" (auditory and linguistic measures, memory tasks, academic achievement levels) and much less related to tasks where even precise hand work ("motor functions") are required <ref>Warner MH, Ernst J, Townes BD, Peel J, Preston M Relationships between IQ and neuropsychological measures in neuropsychiatric populations: within-laboratory and cross-cultural replications using WAIS and WAIS-R. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1987 Oct;9(5):545-62. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=pubmed&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=3667899&ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVAbstractPlus PubMed link] </ref> | |

| − | + | A [[meta-analysis]] (Hunter and Hunter, 1984)<ref name="Hunter84" /> which pooled validity results across many studies encompassing thousands of workers (32,124 for cognitive ability), reports that the validity of cognitive ability for entry-level jobs is 0.54, larger than any other measure including job try-out (0.44), experience (0.18), interview (0.14), age (−0.01), education (0.10), and biographical inventory (0.37). This implies that, across a wide range of occupations, intelligence test performance accounts for some 29% of the variance in job performance. | |

| − | + | According to Marley Watkins and colleagues, IQ is a causal influence on future academic achievement, whereas academic achievement does not substantially influence future IQ scores.<ref>Marley W. Watkins, Pui-Wa Lei and Gary L. Canivez, Psychometric intelligence and achievement: A cross-lagged panel analysis, Intelligence, Volume 35, Issue 1, January-February 2007, Pages 59-68.</ref> Treena Eileen Rohde and Lee Anne Thompson write that general cognitive ability but not specific ability scores predict academic achievement, with the exception that processing speed and spatial ability predict performance on the SAT math beyond the effect of general cognitive ability.<ref>Treena Eileen Rohde and Lee Anne Thompson, Predicting academic achievement with cognitive ability, Intelligence, Volume 35, Issue 1, January-February 2007, Pages 83-92.</ref> | |

| + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> states that other individual characteristics such as interpersonal skills, aspects of personality, etc., are probably of equal or greater importance, but at this point we do not have equally reliable instruments to measure them.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Income === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some researchers claim that "in economic terms it appears that the IQ score measures something with decreasing marginal value. It is important to have enough of it, but having lots and lots does not buy you that much."<ref>Detterman and Daniel, 1989.</ref><ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.americanscientist.org/template/AssetDetail/assetid/24538/page/4 | ||

| + | |title=The Role of Intelligence in Modern Society | ||

| + | |pages=4 (Nonlinearities in Intelligence) | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6|accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |datemonth=July|dateyear=1995 | ||

| + | |author=Earl Hunt | ||

| + | |publisher=American Scientist | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other studies show that ability and performance for jobs are linearly related, such that at all IQ levels, an increase in IQ translates into a concomitant increase in performance <ref>Coward, W.M. and Sackett, P.R. (1990). Linearity of ability-performance relationships: A reconfirmation. ''Journal of Applied Psychology,'' 75:297–300.</ref>. Charles Murray, coauthor of ''[[The Bell Curve]]'', found that IQ has a substantial effect on income independently of family background <ref>Murray, Charles (1998). Income Inequality and IQ, AEI Press [http://www.aei.org/docLib/20040302_book443.pdf PDF]</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> states that IQ scores account for about one-fourth of the social status variance and one-sixth of the income variance. Statistical controls for parental SES eliminate about a quarter of this predictive power. Psychometric intelligence appears as only one of a great many factors that influence social outcomes.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | One reason why some studies claim that IQ only accounts for a sixth of the variation in income is because many studies are based on young adults (many of whom have not yet completed their education). On pg 568 of [[The g factor]], [[Arthur Jensen]] claims that although the correlation between IQ and income averages a moderate 0.4 (one sixth or 16% of the variance), the relationship increases with age, and peaks at middle age when people have reached their maximum career potential. In the book, a [[Question of Intelligence]], [[Daniel Seligman]] cites an IQ income correlation of 0.5 (25% of the variance). | ||

| + | |||

| + | A 2002 study<ref>[http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/aea/jep/2002/00000016/00000003/art00001 The Inheritance of Inequality] Bowles, Samuel; Gintis, Herbert. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 16, Number 3, 1 August 2002, pp. 3-30(28)</ref> further examined the impact of non-IQ factors on income and concluded that an offspring's inherited wealth, race, and schooling are more important as factors in determining income than IQ. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Other correlations with IQ === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, IQ and its correlation to health, [[violent crime]], [[gross state product]], and government effectiveness are the subject of a 2006 paper in the publication ''Intelligence''. The paper breaks down IQ averages by U.S. states using the federal government's [[National Assessment of Educational Progress]] math and reading test scores as a source.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.people.vcu.edu/~mamcdani/Publications/McDaniel%20(2006)%20Estimating%20state%20IQ.pdf | ||

| + | |title=Estimating state IQ: Measurement challenges and preliminary correlates | ||

| + | |accessmonthday= |accessyear= | ||

| + | |date=accepted for publication August 2006 | ||

| + | |author= Michael A. McDaniel, Virginia Commonwealth University | ||

| + | |publisher=Intelligence | ||

| + | |format=PDF | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is a correlation of -.19 between IQ scores and number of juvenile offences in a large Danish sample; with social class controlled, the correlation dropped to -. 17. Similarly, the correlations for most "negative outcome" variables are typically smaller than .20, which means that test scores are associated with less than 4% of their total variance. It is important to realize that the causal links between psychometric ability and social outcomes may be indirect. Children who are unsuccessful in - and hence alienated from - school may be more likely to engage in delinquent behaviours for that very reason, compared to other children who enjoy school and are doing well.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | IQ is also associated with [[Health and intelligence#Association with other diseases|certain diseases]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The book ''[[IQ and the Wealth of Nations]]'' claims to show that the [[GDP]]/person of a nation can in large part be explained by the average IQ score of its citizens. This claim has been both disputed and supported in peer-reviewed papers. The data used have also been questioned. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tambs ''et al.'' (1989)<ref>Tambs K, Sundet JM, Magnus P, Berg K. "Genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance between occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ: a study of twins." Behav Genet. 1989 Mar;19(2):209–22. PMID 2719624.</ref> found that occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ are individually heritable; and further found that "genetic variance influencing educational attainment … contributed approximately one-fourth of the genetic variance for occupational status and nearly half the genetic variance for IQ." In a sample of U.S. siblings, Rowe ''et al.'' (1997)<ref>Rowe, D. C., W. J. Vesterdal, and J. L. Rodgers, "The Bell Curve Revisited: How Genes and Shared Environment Mediate IQ-SES Associations," University of Arizona, 1997</ref> report that the inequality in education and income was predominantly due to genes, with shared environmental factors playing a subordinate role. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some argue that IQ scores are used as an excuse for not trying to reduce poverty or otherwise improve living standards for all. Claimed low intelligence has historically been used to justify the [[feudal system]] and unequal treatment of women (but note that many studies find identical average IQs among men and women; see [[sex and intelligence]]). In contrast, others claim that the refusal of "high-IQ elites" to take IQ seriously as a cause of inequality is itself immoral.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.isteve.com/How_to_Help_the_Left_Half_of_the_Bell_Curve.htm | ||

| + | |title=How to Help the Left Half of the Bell Curve | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |datemonth=July|dateyear=2000 | ||

| + | |author=Steve Sailer | ||

| + | |publisher=VDARE.com | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Heritability== | ||

The role of genes and environment (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ is reviewed in Plomin ''et al.'' (2001, 2003). The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called heritability. Heritability scores range from 0 to 1, and can be interpreted as the percentage of variation (e.g. in IQ) that is due to variation in genes. Twin and adoption studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait. Until recently heritability was mostly studied in children. These studies find the heritability of IQ is approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. A heritability of 0.5 implies that IQ is "substantially" heritable. Studies with adults show that they have a higher heritability of IQ than children do and that heritability could be as high as 0.8. The [[American Psychological Association]]'s 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the White population the heritability of IQ is "around .75" (p. 85).[http://www.lrainc.com/swtaboo/taboos/apa_01.html] | The role of genes and environment (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ is reviewed in Plomin ''et al.'' (2001, 2003). The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called heritability. Heritability scores range from 0 to 1, and can be interpreted as the percentage of variation (e.g. in IQ) that is due to variation in genes. Twin and adoption studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait. Until recently heritability was mostly studied in children. These studies find the heritability of IQ is approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. A heritability of 0.5 implies that IQ is "substantially" heritable. Studies with adults show that they have a higher heritability of IQ than children do and that heritability could be as high as 0.8. The [[American Psychological Association]]'s 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the White population the heritability of IQ is "around .75" (p. 85).[http://www.lrainc.com/swtaboo/taboos/apa_01.html] | ||

| Line 101: | Line 156: | ||

Shared family effects also seem to disappear by adulthood. Adoption studies show that, after adolescence, adopted siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monzygotic or identical twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than fraternal or dizygotic twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adopted siblings (~0.0).<ref>Plomin ''et al.'' (2001, 2003)</ref> | Shared family effects also seem to disappear by adulthood. Adoption studies show that, after adolescence, adopted siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monzygotic or identical twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than fraternal or dizygotic twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adopted siblings (~0.0).<ref>Plomin ''et al.'' (2001, 2003)</ref> | ||

| − | ==IQ | + | |

| + | ==Group differences== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among the most controversial issues related to the study of intelligence is the observation that intelligence measures such as IQ scores vary between populations. While there is little scholarly debate about the ''existence'' of some of these differences, the ''reasons'' remain highly controversial both within academia and in the public sphere. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Health and IQ=== | ||

| + | {{main|Health and intelligence}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Persons with a higher [[IQ]] have generally lower adult [[morbidity]] and [[mortality]]. [[Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder]],<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/63/11/1238 | ||

| + | |title= Intelligence and Other Predisposing Factors in Exposure to Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. A Follow-up Study at Age 17 Years | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=11, November 2006 | ||

| + | |author= Naomi Breslau, PhD; Victoria C. Lucia, PhD; German F. Alvarado, MD, MPH | ||

| + | |publisher= Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1238-1245 | ||

| + | }}</ref> severe [[clinical depression|depression]], <ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=1572949&dopt=Citation Effects of major depression on estimates of intelligence] Sackeim HA, Freeman J, McElhiney M, Coleman E, Prudic J, Devanand DP. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992 Mar;14(2):268-88.</ref><ref>[http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01564.x Improvement of cognitive functioning in mood disorder patients with depressive symptomatic recovery during treatment: An exploratory analysis] LAURA MANDELLI, Psy. D, ALESSANDRO SERRETTI, md,1 CRISTINA COLOMBO, md, MARCELLO FLORITA, Psy. D, ALESSIA SANTORO, Psy. D, DAVID ROSSINI, MD, RAFFAELLA ZANARDI, MD AND ENRICO SMERALDI, MD. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences Volume 60 Issue 5 Page 598 - October 2006</ref> | ||

| + | and [[schizophrenia]] are less prevalent in higher IQ bands. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A study of 11,282 individuals in Scotland who took intelligence tests at ages 7, 9 and 11 in the 1950s and 1960s, found an "inverse linear association" between childhood IQ scores and hospital admissions for injuries in adulthood. The association between childhood IQ and the risk of later injury remained even after accounting for factors such as the child's socioeconomic background.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.ajph.org/cgi/content/abstract/AJPH.2005.080168v1 | ||

| + | |title=Associations Between Childhood Intelligence and Hospital Admissions for Unintentional Injuries in Adulthood: The Aberdeen Children of the 1950s Cohort Study | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=January 10 |accessyear=2007 | ||

| + | |date=2006 | ||

| + | |author= Debbie A. Lawlor, University of Bristol, Heather Clark, University of Aberdeen, David A. Leon, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine | ||

| + | |publisher=American Journal of Public Health, December 2006}}</ref> | ||

| + | Research in Scotland has also shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/322/7290/819 | ||

| + | |title=Longitudinal cohort study of childhood IQ and survival up to age 76 | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=2001 | ||

| + | |author=Whalley and Deary | ||

| + | |publisher=British Medical Journal 2001, 322:819-819 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A decrease in IQ has also been shown as an early predictor of late-onset [[Alzheimer's Disease]] and other forms of [[dementia]]. In a 2004 study, Cervilla and colleagues showed that tests of cognitive ability provide useful predictive information up to a decade before the onset of dementia.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.jnnp.com/cgi/content/abstract/75/8/1100 | ||

| + | |title= Premorbid cognitive testing predicts the onset of dementia and Alzheimer's disease better than and independently of APOE genotype | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=2004 | ||

| + | |author=Cervilla et al | ||

| + | |publisher=Psychiatry 2004;75:1100-1106. | ||

| + | }}</ref> However, when diagnosing individuals with a higher level of cognitive ability, in this study those with IQ's of 120 or more,<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://laboratory-manager.advanceweb.com/common/editorial/editorial.aspx?CC=27318 | ||

| + | |title= More Sensitive Test Norms Better Predict Who Might Develop Alzheimer's Disease | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date= | ||

| + | |author= Dorene Rentz, Brigham and Women's Hospital's Department of Neurology and Harvard Medical School | ||

| + | |publisher= Neuropsychology, published by the American Psychological Association | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | patients should not be diagnosed from the standard norm but from an adjusted high-IQ norm that measured changes against the individual's higher ability level. In 2000, Whalley and colleagues published a paper in the journal ''Neurology'', which examined links between childhood mental ability and late-onset dementia. The study showed that mental ability scores were significantly lower in children who eventually developed late-onset dementia when compared with other children tested.<ref>{{Cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/55/10/1455 | ||

| + | |title= Childhood mental ability and dementia | ||

| + | |accessmonthday=August 6 |accessyear=2006 | ||

| + | |date=2000 | ||

| + | |author=Whalley ''et al.'' | ||

| + | |publisher=Neurology 2000;55:1455-1459. | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several factors can lead to significant cognitive impairment, particularly if they occur during pregnancy and childhood when the brain is growing and the [[blood-brain barrier]] is less effective. Such impairment may sometimes be permanent, or may sometimes be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth. Several harmful factors may also combine, possibly causing greater impairment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Developed nations have implemented several health policies regarding nutrients and toxins known to influence cognitive function. These include laws requiring [[food fortification|fortification]] of certain food products and laws establishing safe levels of pollutants (e.g. lead, mercury, and organochlorides). Comprehensive policy recommendations targeting reduction of cognitive impairment in children have been proposed.<ref name="Olness">Olness, K. "[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&list_uids=12692458&dopt=Citation Effects on brain development leading to cognitive impairment: a worldwide epidemic]," ''Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics'' 24, no. 2 (2003): 120–30.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In terms of the effect of one's intelligence on health, high childhood IQ correlates with one's chance of becoming a vegetarian in adulthood ({{cite journal | ||

| + | | last =Gale | ||

| + | | first =CR | ||

| + | | authorlink = | ||

| + | | coauthors = | ||

| + | | title =IQ in childhood and vegetarianism in adulthood: 1970 British cohort study | ||

| + | | journal =British Journal of Medicine | ||

| + | | volume =334 | ||

| + | | issue =7587 | ||

| + | | pages =245 | ||

| + | | date = | ||

| + | | url = | ||

| + | | doi = | ||

| + | | id = | ||

| + | | accessdate = }}), and inversely correlates with the chances of smoking ({{cite journal | ||

| + | | last =Taylor | ||

| + | | first =MD | ||

| + | | authorlink = | ||

| + | | coauthors = | ||

| + | | title =Childhood IQ and social factors on smoking behaviour, lung function and smoking-related outcomes in adulthood: linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies | ||

| + | | journal =British Journal of Health Psychology | ||

| + | | volume =10 | ||

| + | | issue =3 | ||

| + | | pages =399-401 | ||

| + | | date = | ||

| + | | url = | ||

| + | | doi = | ||

| + | | id = | ||

| + | | accessdate = }}), becoming obese, and having serious traumatic accidents in adulthood. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Gender and IQ=== | ||

| + | {{main|Sex and intelligence}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sex and intelligence research investigates differences in the distributions of cognitive skills between men and women. This research employs experimental tests of cognitive ability, which take a variety of forms, including written tests like the [[SAT]]. Research has focused on differences in individual skills as well as overall differences in [[general intelligence factor|general cognitive ability]], which is often called ''g''. [[Intelligence quotient|IQ tests]], specially designed to measure cognitive ability, usually test a variety of skills, and IQ scores are often used as a measure of ''g''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The populations of men and women differ on average in how well they perform on some of these skill tests, but do equally well on other tests. For example, women tend to score higher on certain verbal and memory tests, whereas men tend to score higher on spatial tests, particularly mental spatial rotations. While these results are relatively uncontroversial, the question of whether men and women differ on average in ''g'' is a matter of debate among experts. Most studies unambiguously find that men as a population are more varied than women in ''g'' (i.e. they have a higher [[variance]] and therefore there are more men than women at the extremes of ability). | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, determining whether men and women differ on average has been more difficult. It is easy to design an IQ test in which either males or females score higher on average, by selecting different tests or giving them different weights, so the question boils down to which weights the different tests should have for the ''g factor''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The primary reason for expecting that men will have higher average ''g'' than women is the male advantage in [[brain]] size. Resolving this question requires the use of sophisticated statistical techniques to extract ''g'' from the results of IQ tests. Some studies find an average male advantage in ''g'', but most do not. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When the Stanford-Binet test was revised in the 1940ies, preliminary test yielded a higher average IQ for women; the test was consequently adjusted to give identical averages for men and women<ref>Quinn McNemar, The Revision of the Stanford-Binet Scale, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1942.</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Jackson and Rushton, a scientific consensus existed during the 20th century that there are no sex differences in overall intelligence.<ref name="Jackson and Rushton"/> They attribute this consensus in part to early work by [[Cyril Burt]]<ref>Burt and Moore, 1912 Burt, C. L., and Moore, R. C. (1912). The mental differences between the sexes. Journal of Experimental Pedagogy, 1, 273–284, 355–388.</ref> and [[Lewis Terman]]<ref>Terman, 1916 L.M. Terman, The measurement of intelligence, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA (1916).</ref> who found no sex differences in the first IQ tests. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A 1994 study by H. Stumpf and [[Douglas N. Jackson]] based on medical school application test scores showed that men averaged IQs about 8.4 points higher than women, while women averaged memories about 7.5 IQ points higher than men.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Stumpf, H. and Jackson, D. N. | title=Gender-related differences in cognitive abilities: evidence from a medical school admissions program | journal=Personality and Individual Differences | year=1994 | volume=17 | pages=335–344}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A 1999 study by [[Richard Lynn]] [http://www.rlynn.co.uk/pages/publications.asp], found that the IQ difference between men and women is typically about 3-4 IQ points, while women usually maintain short-term memory advantages over men of about 2 IQ points. In a 2005 study published in the ''British Journal of Psychology'' <ref>[[Paul Irwing]], [[Richard Lynn]], "[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=16248939&query_hl=19&itool=pubmed_docsum Sex differences in means and variability on the progressive matrices in university students: a meta-analysis]," ''[[British Journal of Psychology]]'', 96(4):505-524, 2005 November.</ref> which attracted media attention in the wake of the January 2005 controversy at Harvard (below),<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/4183166.stm BBC reporting Lynn & Irwing study, 2005]</ref><ref>[http://observer.guardian.co.uk/focus/story/0,6903,1635380,00.html Guardian reporting Lynn & Irwing study and Blinkhorn's reply, 2005]</ref> he and [[Paul Irwing]] analyzed existing studies to report that university men have an average IQ between 3.3 and 5.0 points higher than that of university women. In ''Nature'', intelligence-test designer [[Steve Blinkhorn]] argued in reply that Lynn and Irwing's analysis was critically flawed, for example by deliberately excluding a large contrary study that made up almost 45% of the subjects in the meta-analysis<ref>Blinkhorn, S. [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v438/n7064/pdf/438031a.pdf ''Intelligence: a gender bender''], Nature 2005 Nov 3;438(7064):31-2.</ref>; in subsequent correspondence in the same journal, Blinkhorn pointed out that their use of meta-analysis was "methodologically inappropriate, statistically bizarre and unsuited to the estimation of subpopulation parameters." <ref>[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v442/n7098/pdf/nature04967.pdf Brief communications. ''Nature'', vol 442, 6 July 2006.] </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some studies claim that men outperform women on average by 3-4 IQ points<ref>http://www.rlynn.co.uk/pages/publications.asp</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Stumpf, H. and Jackson, D. N. | title=Gender-related differences in cognitive abilities: evidence from a medical school admissions program | journal=Personality and Individual Differences | year=1994 | volume=17 | pages=335–344}}</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Evidence ''against'' differences in overall average IQ scores between men and women has come from several very large and representative studies.<ref name="Hedges and Nowell">{{cite journal | author=Larry V. Hedges; Amy Nowell | title=Sex Differences in Mental Test Scores, Variability, and Numbers of High-Scoring Individuals | journal=Science | year=1995 | volume=269 | pages=41-45}}</ref> However, these studies did find that the scores of men show greater [[variance]] than the scores of women, and that men and women have some differences in average scores on tests of particular abilities, which tend to balance out in overall IQ scores. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Deary ''et al.'' (2003) performed an analysis of an IQ test administered to almost all children in Scotland at age 11 in 1932 (>80,000).<ref name="Deary 2003">{{cite journal | author=IJ Deary, G Thorpe, V Wilson, JM Starr, LJ Whalley | title=Population sex differences in IQ at age 11: the Scottish mental survey 1932 | journal=Intelligence | year=2003 | volume=31 | pages=533–542}}</ref> The average IQ scores by sex were 100.64 for girls and 100.48 for boys. The difference in mean IQ was not significant. However, the standard deviation was 14.1 for girls and 14.9 for boys. This difference was statistically significant. In the sample studied, 49.6% are girls and 50.4% are boys. Because of the difference in variance between the sexes, however, girls are in excess by 2% in the middle IQ range of 90–115. At the extreme IQ ranges, 50–60 and 130–140, boys make up 58.6% and 57.7% of the population (gaps of 17.2% and 15.4%) respectively. That is, boys were overrepresented amongst the lowest and highest IQ groups. It is generally observed that males tend to hit the most positive and negative performance results of many tests. | ||

| + | |||

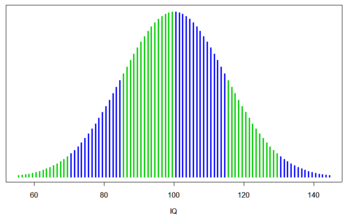

| + | [[Image:Normal distribution pdf.png|thumb|left|300px|Comparing Groups]]The average scores of young men and women in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores. In this sense, the red [[normal distribution|bell curve]] in the diagram represents women, compared to men in green.<ref>Camilla Persson Benbow and Julian C Stanley, 'Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts', ''Science'' 222 (1983): 1029-1031.</ref> There is evidence to suggest that forms of [[autism]] may be essentially extreme expressions of certain typically male characteristics.<ref> | ||

| + | [[Simon Baron-Cohen]], | ||

| + | [http://www.autismresearchcentre.com/docs/papers/1999_BC_extrememalebrain.pdf 'The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism',] | ||

| + | in H Tager-Flusberg (ed.), ''Neurodevelopmental Disorders'', (Boston: The MIT Press, 1999).</ref> <ref>Simon Baron-Cohen. ''Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind''. (Boston: The MIT Press, 1997).</ref> This is represented by the blue in the diagram. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A 2001 report by Richard J. Coley of the ETS found that females often outperformed males on various measures of verbal ability, while males tended to outperform females on measures of mathematical and spatial ability. [http://www.ets.org/research/pic/gender.pdf] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Spatial abilities: large differences favoring males are found in performance on visual-spatial tasks (e.g., mental rotation) and spatio-temporal tasks (e.g., tracking a moving object through space).<ref name="APA">[[Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns]]</ref> The male advantage in visual-spatial tasks is approximately 1 standard deviation. The difference starts at twelve to sixteen years of age<ref>Siann (1977)</ref>. | ||

| + | *Verbal abilities: a range of differences, some large, favoring females are found in performance on verbal tasks. Males also show higher levels of [[dyslexia]] and other reading disabilities. The incidence of [[stuttering]] is also higher among males. | ||

| + | *Memory: Several studies have shown women are better at certain types of memory. <ref>[http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=00018E9D-879D-1D06-8E49809EC588EEDF Sex Differences in the Brain]: Men and women display patterns of behavioral and cognitive differences that reflect varying hormonal influences on brain development- By Doreen Kimura May 13, 2002.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | *General knowledge: A study by Richard Lynn showed that men have more [[general knowledge]] than women.<ref>[http://www.rlynn.co.uk/pages/publications.asp Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen IQ and Global Inequality. (2006).]</ref> | ||

| + | *Education: In the United States, women tend to outnumber men at colleges and universities, except at technical institutions that emphasize math and science such as [[MIT]] and [[Caltech]], where men predominate.<ref name="NBR">[http://www.nber.org/digest/jan07/w12139.html Why Do Women Outnumber Men in College?]</ref><ref>[http://www.uwire.com/content/topnews120502003.html More black women than men in college, journal finds] by Seung Hwa Hong, Daily Trojan (U. Southern California) 12/05/2002</ref> | ||

| + | *Academia: Men outnumber women in tenured faculty positions in math and science. Women outnumber men in tenured faculty positions in humanities fields. | ||

| + | *[[High IQ society|High IQ societies]]: In all "high IQ societies" men outnumber women; e.g., in [[Mensa International|Mensa]] the male-to-female ratio is 2:1. | ||

| + | *Boys tend to have a higher incidence of behavioral problems in schools which may affect academic achievement.<ref name="NBR">..</ref> | ||

| + | |||

===Race and IQ=== | ===Race and IQ=== | ||

| + | {{main|Race and intelligence}} | ||

| + | Much research has been devoted to the extent and potential causes of racial group differences in IQ. | ||

| − | + | Theories about the possibility of a relationship between race and [[intelligence]] have been the subject of speculation and debate since the [[16th century]].<ref>Andor, L. E., ed. ''Aptitudes and Abilities of the Black Man in Sub-Saharan Africa: 1784-1963: An Annotated Bibliography''. Johannesburg: National | |

| + | Institute for Personnel Research, 1966.</ref><ref>"''Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race.''" by Audrey Smedley and Brian D. Smedley[http://www.apa.org/journals/releases/amp60116.pdf]</ref> The contemporary debate focuses on the nature, causes, and importance, or lack of importance, of [[ethnic group|ethnic]] differences in [[intelligence quotient|intelligence test]] scores and other measures of [[cognitive ability]], and whether "race" is a meaningful biological construct with significance other than its correlation to membership of particular ethnic groups. Thus, the question of the relative roles of nature and nurture in | ||

| + | causing individual and group differences in cognitive ability is seen as fundamental to understanding the debate.<ref name="30yrs240">[http://psychology.uwo.ca/faculty/rushtonpdfs/PPPL1.pdf Thirty Years of Research on Race Differences In Cognitive Ability. p. 240]</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | The modern controversy surrounding intelligence and race focuses on the results of IQ studies conducted during the second half of the 20th century in the [[United States]], [[Western Europe]], and other industrialized nations.<ref>[http://www.innovations-report.de/html/berichte/studien/bericht-43536.html Black-White-East Asian IQ differences at least 50% genetic, major law review journal concludes]</ref> |

| − | + | Modern theories and research on race and intelligence are often grounded in two controversial assumptions: | |

| + | * that the social categories of [[race]] and [[ethnicity]] are [[concordance (genetics)|concordant]] with [[genetics|genetic]] categories, such as [[biogeographic ancestry]], and | ||

| + | * that [[intelligence]] is quantitatively measurable by modern tests and is dominated by a unitary "[[general intelligence factor]]" | ||

| + | While the general intelligence factor is an accepted and widespread view of the structure of abilities, some theorists regard it as misleading.<ref>[[Stephen J. Ceci]] (1990). On intelligence more or less: A bioecological treatise on intellectual development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice | ||

| + | Hall</ref>There are a wide range of human abilities, including many that seem to have intellectual components which are outside the domain of standard psychometric tests.<ref>[[American Psychologist]], [http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/research/Correlation/Intelligence.pdf Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns], February 1996</ref> Most of the research is based on [[IQ test]]ing of blacks and whites in the United States, and much of the current debate centers around which environmental factors may influence IQ scores the most, and whether or not there are genetic differences between races that play a significant role in creating the gap, this last question being the most controversial in the debate. | ||

| − | + | Environmental factors, such as [[nutrition]], have been shown to influence IQ in children. Other environmental factors include: education level, richness of the early home environment, the existence of caste-like minorities, socio-economic factors, culture, [[pidgin]] language barriers, quality of education, [[Health and intelligence|health]], [[racism]], lack of positive role-models, exposure to [[violence]], the [[Flynn effect]], [[sociobiological]] differences and [[stereotype threat]]. There is also significant debate about exactly how environmental factors play their role in creating the gap and the interrelationships between these factors. | |

| − | + | The more controversial part of the debate is whether group IQ differences are caused in part by genetic differences. [[Hereditarianism]] hypothesizes that a [[inheritance of intelligence|genetic contribution to intelligence]] includes genes linked to brain anatomy or physiology that vary by race. These kinds of hypotheses have drawn a great deal of media attention and criticism. [[Robert Sternberg]] writes that race intelligence research that focuses on a genetic cause for the gap is attempting to show that one group is inferior to another group.<ref>''There are no public-policy implications: A reply to Rushton and Jensen (2005)'' Robert Sternberg</ref> The conclusion of some researchers: that racial groups in the US vary in average IQ scores in part because of genetic differences between races has led to heated academic debates that have spilled over into the public sphere. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Observations about race and intelligence also have important applications for critics of the media portrayal of race. Stereotypes in media such as books, music, film, and television can reinforce racial stereotypes and may influence the perceived opportunities for success in academics for minority students.<ref>Entman, Robert M. and Andrew Rojecki ''The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America'' 2001</ref><ref>''Darwin's Athletes: how sport has damaged Black America and preserved the myth of race'' By [[John Milton Hoberman]]. ISBN 0395822920</ref> | |

==Criticism and views== | ==Criticism and views== | ||

| Line 146: | Line 341: | ||

=== Test bias === | === Test bias === | ||

| − | + | ||

The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> states that that IQ tests as predictors of social achievement are not biased against people of African descent since they predict future performance, such as school achievement, similarly to the way they predict future performance for European descent.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | The [[American Psychological Association]]'s report ''Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns'' (1995)<ref name="Neisser95" /> states that that IQ tests as predictors of social achievement are not biased against people of African descent since they predict future performance, such as school achievement, similarly to the way they predict future performance for European descent.<ref name="Neisser95" /> | ||

Revision as of 22:24, 5 December 2007

An intelligence quotient or IQ is a score derived from a set of standardized tests of intelligence. Intelligence tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtests scores. Regardless of design, all IQ tests measure the same general intelligence factor also referred to as "g." Component tests are generally designed and chosen because they are found to be predictable of later intellectual development. In some studies, IQ has been shown to correlate with job performance, socioeconomic advancement, and other "social pathologies." Recent work has demonstrated links between IQ and health, longevity, and functional literacy. However, IQ tests have engendered much controversy and it is important to note that they do not measure all meanings of "intelligence." IQ scores are relative. Meaning, that the placement of an IQ score is similar to a placement in a race as they are both dependent upon the performance of the other participants.

History

In 1905, the French psychologist Alfred Binet published the first modern test of intelligence. His principal goal was to identify students who needed special help in coping with the school curriculum. Along with his collaborator Theodore Simon, Binet published revisions of his Binet-Simon intelligence scale in 1908 and 1911, the last appearing just before his untimely death. In 1912, the abbreviation of "intelligence quotient" or IQ, a translation of the German Intelligenz-quotient, was coined by the German psychologist William Stern.

A further refinement of the Binet-Simon scale was published in 1916 by Lewis M. Terman, from Stanford University, who incorporated Stern's proposal that an individual's intelligence level be measured as an intelligence quotient (IQ). Terman's test, which he named the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale formed the basis for one of the modern intelligence tests still commonly used today.

Originally, IQ was calculated as a ratio with the formula

A 10-year-old who scored as high as the average 13-year-old, for example, would have an IQ of 130 (100*13/10).

In 1939 David Wechsler published the first intelligence test explicitly designed for an adult population, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, or WAIS. Since publication of the WAIS, Wechsler extended his scale downward to create the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, or WISC. The third edition of the WAIS (WAIS-III) is the most widely used psychological test in the world, and the fourth edition of the WISC (WISC-IV) is the most widely used intelligence test for children. The Wechsler scales contained separate subscores for verbal and performance IQ, thus being less dependent on overall verbal ability than early versions of the Stanford-Binet scale, and was the first intelligence scale to base scores on a standardized normal distribution rather than an age-based quotient.

Since the publication of the WAIS, almost all intelligence scales have adopted the normal distribution method of scoring. The use of the normal distribution scoring method makes the term "intelligence quotient" an inaccurate description of the intelligence measurement, but "IQ" still enjoys colloquial usage, and is used to describe all of the intelligence scales currently in use.

IQ testing

Structure

IQ tests come in many forms, and some tests use a single type of item or question, while others use several different subtests. Most tests yield both an overall score and individual subtest scores.

A typical IQ test requires the test subject to solve a fair number of problems in a set time under supervision. Most IQ tests include items from various domains, such as short-term memory, verbal knowledge, spatial visualization, and perceptual speed. Some tests have a total time limit, others have a time limit for each group of problems, and there are a few untimed, unsupervised tests, typically geared to measuring high intelligence. The widely used standardized test for determining IQ, the WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III), consists of fourteen subtests, seven verbal (Information, Comprehension, Arithmetic, Similarities, Vocabulary, Digit Span, and Letter-Number Sequencing) and seven performance (Digit Symbol-Coding, Picture Completion, Block Design, Matrix Reasoning, Picture Arrangement, Symbol Search, and Object Assembly).

Scoring

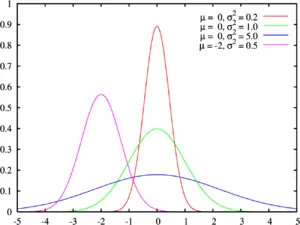

When standardizing an IQ test, a representative sample of the population is tested using each test question. IQ tests are calibrated in such a way as to yield a normal distribution, or "bell curve." Each IQ test, however, is designed and valid only for a certain IQ range. Because so few people score in the extreme ranges, IQ tests usually cannot accurately measure very low and very high IQs.

Various IQ tests measure a standard deviation with a different number of points. Thus, when an IQ score is stated, the standard deviation used should also be stated.

When an individual has scores that do not correlate with each other, there is a good reason to suspect a learning disability or other cause for this lack of correlation. Tests have been chosen for inclusion because they display the ability to use this method to predict later difficulties in learning.

An individual's IQ score may or may not be stable over the course of the individual's lifetime.[1]

IQ and general intelligence factor

Modern IQ tests produce scores for different areas (e.g., language fluency, three-dimensional thinking), with the summary score calculated from subtest scores. The average score, according to the bell curve, is 100. Individual subtest scores tend to correlate with one another, even when seemingly disparate in content.

Mathematical analysis of individuals' scores on the subtests of a single IQ test or the scores from a variety of different IQ tests (e.g., Stanford-Binet, WISC-R, Raven's Progressive Matrices, Cattell Culture Fair III, Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test, Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, and others) find that they can be described mathematically as measuring a single common factor and various factors that are specific to each test. This kind of factor analysis has led to the theory that underlying these disparate cognitive tasks is a single factor, termed the general intelligence factor (or g), that corresponds with the common-sense concept of intelligence.[2] In the normal population, g and IQ are roughly 90% correlated and are often used interchangeably.

Tests differ in their g-loading, which is the degree to which the test score reflects g rather than a specific skill or "group factor" (such as verbal ability, spatial visualization, or mathematical reasoning).

Mental handicaps

Individuals with an unusually low IQ score, varying from about 70 ("Educable Mentally Retarded") to as low as 20 (usually caused by a neurological condition), are considered to have developmental difficulties. However, there is no true IQ-based classification for developmental disabilities.

Positive correlations with IQ

While IQ is sometimes treated as an end unto itself, scholarly work on IQ focuses to a large extent on IQ's validity, that is, the degree to which IQ correlates with outcomes such as job performance, social pathologies, or academic achievement. Different IQ tests differ in their validity for various outcomes. Traditionally, correlation for IQ and outcomes is viewed as a means to also predict performance; however, because IQ is a known social artifact, readers should distinguish between prediction in the hard sciences and the social sciences.

Validity is the correlation between score (in this case cognitive ability, as measured, typically, by a paper-and-pencil test) and outcome (in this case job performance, as measured by a range of factors including supervisor ratings, promotions, training success, and tenure), and ranges between −1.0 (the score is perfectly wrong in predicting outcome) and 1.0 (the score perfectly predicts the outcome). See validity (psychometric).

Research shows that general intelligence plays an important role in many valued life outcomes. In addition to academic success, IQ correlates to some degree with job performance (see below), socioeconomic advancement (e.g., level of education, occupation, and income), and "social pathology" (e.g., adult criminality, poverty, unemployment, dependence on welfare, children outside of marriage). Recent work has demonstrated links between general intelligence and health, longevity, and functional literacy. Correlations between g and life outcomes are pervasive, though IQ does not correlate with subjective self-reports of happiness. IQ and g correlate highly with school performance and job performance, less so with occupational prestige, moderately with income, and to a small degree with law-abiding behaviour. IQ does not explain the inheritance of economic status and wealth.

Other tests

One study found a correlation of .82 between g and SAT scores.[2] Another correlation of .81 between g and GCSE scores.[3]

Correlations between IQ scores (general cognitive ability) and achievement test scores are reported to be .81 by Deary and colleagues, with the percentage of variance accounted for by general cognitive ability ranging "from 58.6% in Mathematics and 48% in English to 18.1% in Art and Design"[3]

School performance

The American Psychological Association's report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995)[1] Wherever it has been studied, children with high scores on tests of intelligence tend to learn more of what is taught in school than their lower-scoring peers. The correlation between IQ scores and grades is about .50. However, this means that they explain only 25% of the variance. Successful school learning depends on many personal characteristics other than intelligence, such as memory, persistence, interest in school, and willingness to study.

Correlations between IQ scores and total years of education are about .55, implying that differences in psychometric intelligence account for about 30% of the outcome variance. Many occupations can only be entered through professional schools which base their admissions at least partly on test scores: the MCAT, the GMAT, the GRE, the DAT, the LSAT, etc. Individual scores on admission-related tests such as these are certainly correlated with scores on tests of intelligence. It is partly because intelligence test scores predict years of education that they also predict occupational status, and income to a smaller extent.

Job performance

According to Schmidt and Hunter, "for hiring employees without previous experience in the job the most valid predictor of future performance is general mental ability."[4] The validity depends on the type of job and varies across different studies, ranging from 0.2 to 0.6 [5]. However IQ mostly correlates with cognitive ability only if IQ scores are below average and this rule has many (about 30 %) exceptions for people with average and higher IQ scores [6]. Also, IQ is related to the "academic tasks" (auditory and linguistic measures, memory tasks, academic achievement levels) and much less related to tasks where even precise hand work ("motor functions") are required [7]

A meta-analysis (Hunter and Hunter, 1984)[5] which pooled validity results across many studies encompassing thousands of workers (32,124 for cognitive ability), reports that the validity of cognitive ability for entry-level jobs is 0.54, larger than any other measure including job try-out (0.44), experience (0.18), interview (0.14), age (−0.01), education (0.10), and biographical inventory (0.37). This implies that, across a wide range of occupations, intelligence test performance accounts for some 29% of the variance in job performance.

According to Marley Watkins and colleagues, IQ is a causal influence on future academic achievement, whereas academic achievement does not substantially influence future IQ scores.[8] Treena Eileen Rohde and Lee Anne Thompson write that general cognitive ability but not specific ability scores predict academic achievement, with the exception that processing speed and spatial ability predict performance on the SAT math beyond the effect of general cognitive ability.[9]

The American Psychological Association's report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995)[1] states that other individual characteristics such as interpersonal skills, aspects of personality, etc., are probably of equal or greater importance, but at this point we do not have equally reliable instruments to measure them.[1]

Income

Some researchers claim that "in economic terms it appears that the IQ score measures something with decreasing marginal value. It is important to have enough of it, but having lots and lots does not buy you that much."[10][11]

Other studies show that ability and performance for jobs are linearly related, such that at all IQ levels, an increase in IQ translates into a concomitant increase in performance [12]. Charles Murray, coauthor of The Bell Curve, found that IQ has a substantial effect on income independently of family background [13].

The American Psychological Association's report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995)[1] states that IQ scores account for about one-fourth of the social status variance and one-sixth of the income variance. Statistical controls for parental SES eliminate about a quarter of this predictive power. Psychometric intelligence appears as only one of a great many factors that influence social outcomes.[1]

One reason why some studies claim that IQ only accounts for a sixth of the variation in income is because many studies are based on young adults (many of whom have not yet completed their education). On pg 568 of The g factor, Arthur Jensen claims that although the correlation between IQ and income averages a moderate 0.4 (one sixth or 16% of the variance), the relationship increases with age, and peaks at middle age when people have reached their maximum career potential. In the book, a Question of Intelligence, Daniel Seligman cites an IQ income correlation of 0.5 (25% of the variance).

A 2002 study[14] further examined the impact of non-IQ factors on income and concluded that an offspring's inherited wealth, race, and schooling are more important as factors in determining income than IQ.

Other correlations with IQ

In addition, IQ and its correlation to health, violent crime, gross state product, and government effectiveness are the subject of a 2006 paper in the publication Intelligence. The paper breaks down IQ averages by U.S. states using the federal government's National Assessment of Educational Progress math and reading test scores as a source.[15]

There is a correlation of -.19 between IQ scores and number of juvenile offences in a large Danish sample; with social class controlled, the correlation dropped to -. 17. Similarly, the correlations for most "negative outcome" variables are typically smaller than .20, which means that test scores are associated with less than 4% of their total variance. It is important to realize that the causal links between psychometric ability and social outcomes may be indirect. Children who are unsuccessful in - and hence alienated from - school may be more likely to engage in delinquent behaviours for that very reason, compared to other children who enjoy school and are doing well.[1]

IQ is also associated with certain diseases.

The book IQ and the Wealth of Nations claims to show that the GDP/person of a nation can in large part be explained by the average IQ score of its citizens. This claim has been both disputed and supported in peer-reviewed papers. The data used have also been questioned.

Tambs et al. (1989)[16] found that occupational status, educational attainment, and IQ are individually heritable; and further found that "genetic variance influencing educational attainment … contributed approximately one-fourth of the genetic variance for occupational status and nearly half the genetic variance for IQ." In a sample of U.S. siblings, Rowe et al. (1997)[17] report that the inequality in education and income was predominantly due to genes, with shared environmental factors playing a subordinate role.

Some argue that IQ scores are used as an excuse for not trying to reduce poverty or otherwise improve living standards for all. Claimed low intelligence has historically been used to justify the feudal system and unequal treatment of women (but note that many studies find identical average IQs among men and women; see sex and intelligence). In contrast, others claim that the refusal of "high-IQ elites" to take IQ seriously as a cause of inequality is itself immoral.[18]

Heritability

The role of genes and environment (nature vs. nurture) in determining IQ is reviewed in Plomin et al. (2001, 2003). The degree to which genetic variation contributes to observed variation in a trait is measured by a statistic called heritability. Heritability scores range from 0 to 1, and can be interpreted as the percentage of variation (e.g. in IQ) that is due to variation in genes. Twin and adoption studies are commonly used to determine the heritability of a trait. Until recently heritability was mostly studied in children. These studies find the heritability of IQ is approximately 0.5; that is, half of the variation in IQ among the children studied was due to variation in their genes. The remaining half was thus due to environmental variation and measurement error. A heritability of 0.5 implies that IQ is "substantially" heritable. Studies with adults show that they have a higher heritability of IQ than children do and that heritability could be as high as 0.8. The American Psychological Association's 1995 task force on "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" concluded that within the White population the heritability of IQ is "around .75" (p. 85).[4]

Environment

Environmental factors play a large role in determining IQ in certain situations. Proper childhood nutrition appears to be critical for cognitive development as malnutrition correlates to lower IQ. Other research indicates environmental factors such as prenatal exposure to toxins, the duration of breastfeeding, and micronutrient deficiency affecting IQ.

Nearly all personality traits show that, contrary to expectations, environmental effects actually cause adoptive siblings raised in the same family to be as different as children who were raised in different families (Harris, 1998; Plomin & Daniels, 1987). IQ is an exception among children. The IQs of adoptive siblings, who share no genetic relation but do share a common family environment, are correlated at .32. Despite attempts to isolate the factors that cause adoptive siblings to be similar, they have not been identified. It is important to note, however, that shared family effects on IQ disappear after adolescence.

Active genotype-environment correlation, also called the "nature of nurture," is observed for IQ. This phenomenon is measured similarly to heritability; but instead of measuring variation in IQ due to genes, variation in environment due to genes is determined. One study found that 40% of variation in measures of home environment are accounted for by genetic variation. This suggests that the way human beings craft their environment is due in part to genetic influences.

A study of French children adopted between the ages of 4 and 6 shows the continuing interplay of nature and nurture. The children came from poor backgrounds with I.Q.’s that averaged 77, putting them near retardation. Nine years later after adoption, they retook the I.Q. tests, and all of them did better. The amount they improved was directly related to the adopting family’s status. "Children adopted by farmers and laborers had average I.Q. scores of 85.5; those placed with middle-class families had average scores of 92. The average I.Q. scores of youngsters placed in well-to-do homes climbed more than 20 points, to 98."[5] This study suggests that IQ is not stable over the course of ones lifetime and that, even in later childhood, a change in individual's environment can have a significant effect on IQ.

Genetics

It is reasonable to expect that genetic influences on traits like IQ should become less important as one gains experiences with age. Surprisingly, the opposite occurs. Heritability measures in infancy are as low as 20%, around 40% in middle childhood, and as high as 80% in adulthood.[19]

Shared family effects also seem to disappear by adulthood. Adoption studies show that, after adolescence, adopted siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monzygotic or identical twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than fraternal or dizygotic twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adopted siblings (~0.0).[20]

Group differences

Among the most controversial issues related to the study of intelligence is the observation that intelligence measures such as IQ scores vary between populations. While there is little scholarly debate about the existence of some of these differences, the reasons remain highly controversial both within academia and in the public sphere.

Health and IQ

Persons with a higher IQ have generally lower adult morbidity and mortality. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,[21] severe depression, [22][23] and schizophrenia are less prevalent in higher IQ bands.

A study of 11,282 individuals in Scotland who took intelligence tests at ages 7, 9 and 11 in the 1950s and 1960s, found an "inverse linear association" between childhood IQ scores and hospital admissions for injuries in adulthood. The association between childhood IQ and the risk of later injury remained even after accounting for factors such as the child's socioeconomic background.[24] Research in Scotland has also shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long.[25]

A decrease in IQ has also been shown as an early predictor of late-onset Alzheimer's Disease and other forms of dementia. In a 2004 study, Cervilla and colleagues showed that tests of cognitive ability provide useful predictive information up to a decade before the onset of dementia.[26] However, when diagnosing individuals with a higher level of cognitive ability, in this study those with IQ's of 120 or more,[27] patients should not be diagnosed from the standard norm but from an adjusted high-IQ norm that measured changes against the individual's higher ability level. In 2000, Whalley and colleagues published a paper in the journal Neurology, which examined links between childhood mental ability and late-onset dementia. The study showed that mental ability scores were significantly lower in children who eventually developed late-onset dementia when compared with other children tested.[28]

Several factors can lead to significant cognitive impairment, particularly if they occur during pregnancy and childhood when the brain is growing and the blood-brain barrier is less effective. Such impairment may sometimes be permanent, or may sometimes be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth. Several harmful factors may also combine, possibly causing greater impairment.

Developed nations have implemented several health policies regarding nutrients and toxins known to influence cognitive function. These include laws requiring fortification of certain food products and laws establishing safe levels of pollutants (e.g. lead, mercury, and organochlorides). Comprehensive policy recommendations targeting reduction of cognitive impairment in children have been proposed.[29]

In terms of the effect of one's intelligence on health, high childhood IQ correlates with one's chance of becoming a vegetarian in adulthood (Gale, CR. IQ in childhood and vegetarianism in adulthood: 1970 British cohort study. British Journal of Medicine 334 (7587): 245.), and inversely correlates with the chances of smoking (Taylor, MD. Childhood IQ and social factors on smoking behaviour, lung function and smoking-related outcomes in adulthood: linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. British Journal of Health Psychology 10 (3): 399-401.), becoming obese, and having serious traumatic accidents in adulthood.

Gender and IQ

Sex and intelligence research investigates differences in the distributions of cognitive skills between men and women. This research employs experimental tests of cognitive ability, which take a variety of forms, including written tests like the SAT. Research has focused on differences in individual skills as well as overall differences in general cognitive ability, which is often called g. IQ tests, specially designed to measure cognitive ability, usually test a variety of skills, and IQ scores are often used as a measure of g.

The populations of men and women differ on average in how well they perform on some of these skill tests, but do equally well on other tests. For example, women tend to score higher on certain verbal and memory tests, whereas men tend to score higher on spatial tests, particularly mental spatial rotations. While these results are relatively uncontroversial, the question of whether men and women differ on average in g is a matter of debate among experts. Most studies unambiguously find that men as a population are more varied than women in g (i.e. they have a higher variance and therefore there are more men than women at the extremes of ability).

However, determining whether men and women differ on average has been more difficult. It is easy to design an IQ test in which either males or females score higher on average, by selecting different tests or giving them different weights, so the question boils down to which weights the different tests should have for the g factor.

The primary reason for expecting that men will have higher average g than women is the male advantage in brain size. Resolving this question requires the use of sophisticated statistical techniques to extract g from the results of IQ tests. Some studies find an average male advantage in g, but most do not.

When the Stanford-Binet test was revised in the 1940ies, preliminary test yielded a higher average IQ for women; the test was consequently adjusted to give identical averages for men and women[30].

According to Jackson and Rushton, a scientific consensus existed during the 20th century that there are no sex differences in overall intelligence.[31] They attribute this consensus in part to early work by Cyril Burt[32] and Lewis Terman[33] who found no sex differences in the first IQ tests.

A 1994 study by H. Stumpf and Douglas N. Jackson based on medical school application test scores showed that men averaged IQs about 8.4 points higher than women, while women averaged memories about 7.5 IQ points higher than men.[34]

A 1999 study by Richard Lynn [6], found that the IQ difference between men and women is typically about 3-4 IQ points, while women usually maintain short-term memory advantages over men of about 2 IQ points. In a 2005 study published in the British Journal of Psychology [35] which attracted media attention in the wake of the January 2005 controversy at Harvard (below),[36][37] he and Paul Irwing analyzed existing studies to report that university men have an average IQ between 3.3 and 5.0 points higher than that of university women. In Nature, intelligence-test designer Steve Blinkhorn argued in reply that Lynn and Irwing's analysis was critically flawed, for example by deliberately excluding a large contrary study that made up almost 45% of the subjects in the meta-analysis[38]; in subsequent correspondence in the same journal, Blinkhorn pointed out that their use of meta-analysis was "methodologically inappropriate, statistically bizarre and unsuited to the estimation of subpopulation parameters." [39]

Some studies claim that men outperform women on average by 3-4 IQ points[40][41].

Evidence against differences in overall average IQ scores between men and women has come from several very large and representative studies.[42] However, these studies did find that the scores of men show greater variance than the scores of women, and that men and women have some differences in average scores on tests of particular abilities, which tend to balance out in overall IQ scores.

Deary et al. (2003) performed an analysis of an IQ test administered to almost all children in Scotland at age 11 in 1932 (>80,000).[43] The average IQ scores by sex were 100.64 for girls and 100.48 for boys. The difference in mean IQ was not significant. However, the standard deviation was 14.1 for girls and 14.9 for boys. This difference was statistically significant. In the sample studied, 49.6% are girls and 50.4% are boys. Because of the difference in variance between the sexes, however, girls are in excess by 2% in the middle IQ range of 90–115. At the extreme IQ ranges, 50–60 and 130–140, boys make up 58.6% and 57.7% of the population (gaps of 17.2% and 15.4%) respectively. That is, boys were overrepresented amongst the lowest and highest IQ groups. It is generally observed that males tend to hit the most positive and negative performance results of many tests.

The average scores of young men and women in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores. In this sense, the red bell curve in the diagram represents women, compared to men in green.[44] There is evidence to suggest that forms of autism may be essentially extreme expressions of certain typically male characteristics.[45] [46] This is represented by the blue in the diagram.

A 2001 report by Richard J. Coley of the ETS found that females often outperformed males on various measures of verbal ability, while males tended to outperform females on measures of mathematical and spatial ability. [7]

- Spatial abilities: large differences favoring males are found in performance on visual-spatial tasks (e.g., mental rotation) and spatio-temporal tasks (e.g., tracking a moving object through space).[47] The male advantage in visual-spatial tasks is approximately 1 standard deviation. The difference starts at twelve to sixteen years of age[48].

- Verbal abilities: a range of differences, some large, favoring females are found in performance on verbal tasks. Males also show higher levels of dyslexia and other reading disabilities. The incidence of stuttering is also higher among males.

- Memory: Several studies have shown women are better at certain types of memory. [49]

- General knowledge: A study by Richard Lynn showed that men have more general knowledge than women.[50]

- Education: In the United States, women tend to outnumber men at colleges and universities, except at technical institutions that emphasize math and science such as MIT and Caltech, where men predominate.[51][52]

- Academia: Men outnumber women in tenured faculty positions in math and science. Women outnumber men in tenured faculty positions in humanities fields.

- High IQ societies: In all "high IQ societies" men outnumber women; e.g., in Mensa the male-to-female ratio is 2:1.

- Boys tend to have a higher incidence of behavioral problems in schools which may affect academic achievement.[51]

Race and IQ

Much research has been devoted to the extent and potential causes of racial group differences in IQ.