Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears refers to the forced relocation in 1838, of the Cherokee Native American tribe to Indian Territory in what would be the state of Oklahoma, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 4,000 of the 15,000 Cherokees affected.[1] This was caused by the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Cherokee Trail of Tears resulted from the enforcement of the Treaty of New Echota, an agreement signed under the provisions of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which exchanged Native American land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River, but which was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people. Nevertheless, the treaty was enforced by President Andrew Jackson, who sent federal troops to round up about 17,000 Cherokees in camps before being sent to the West. Most of the deaths occurred from disease in these camps. After the initial roundup, the U.S. military played a limited role in the journey itself, with the Cherokee Nation taking over supervision of most of the emigration.

In the Cherokee language, the event is called nvnadaulatsvyi ("The Trail Where We Cried"). The Cherokees were not the only Native Americans forced to emigrate as a result of the Indian Removal efforts of the United States, and so the phrase "Trail of Tears" is sometimes used to refer to similar events endured by other Native peoples, especially among the "Five Civilized Tribes." The phrase originated as a description of the earlier removal of the Choctaw nation, the first to march a "Trail of Tears."

Georgia and the Cherokee Nation

The rapidly expanding United States population of the early nineteenth century encroached upon the American Indian tribal lands of various states. While state governments did not want independent Native enclaves within state boundaries, Native tribes did not want to relocate or give up their distinct identities.

With the Compact of 1802, the state of Georgia relinquished to the national government its western land claims (which became the states of Alabama and Mississippi). In return, the federal government promised to precipitate the relocation of the American Indian tribes of Georgia, thus securing for Georgia complete control of all land within its borders.

Gold rush and court cases

Tensions between Georgia and the Cherokee Nation were exacerbated by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia in 1829, and the subsequent Georgia Gold Rush, the first gold rush in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure mounted on the Georgian government to fulfill the promises of the Compact of 1802.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee tribal lands in 1830, the matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Marshall court ruled that the Cherokees were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national governmentânot state governmentsâhad authority in Native American affairs.

President Andrew Jackson has often been quoted as defying the Supreme Court with the words: "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" Jackson probably never said this, although he was fully committed to the policy of Indian removal. He had no desire to use the power of the federal government to protect the Cherokees from Georgia, since he was already entangled with states' rights issues in what became known as the Nullification Crisis. With the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the United States Congress had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty.[2]

Removal treaty and resistance

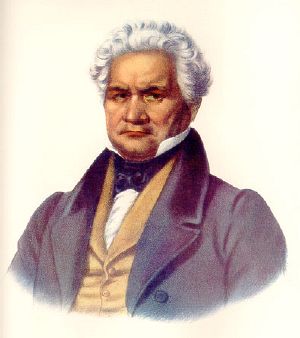

With the landslide reelection of Andrew Jackson in 1832, some of the most strident Cherokee opponents of removal began to rethink their positions. Led by Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and nephews Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie, they became known as the "Ridge Party," or the "Treaty Party." The Ridge Party believed that it was in the best interest of the Cherokees to get favorable terms from the U.S. government, before white squatters, state governments, and violence made matters worse. John Ridge began unauthorized talks with the Jackson administration in the late 1820s. Meanwhile, in anticipation of the Cherokee removal, the state of Georgia began holding lotteries in order to divide up the Cherokee tribal lands among its citizenry.

However, elected principal Chief John Ross and the majority of the Cherokee people remained adamantly opposed to removal. Political maneuvering began: Chief Ross canceled the tribal elections in 1832, the Council impeached the Ridges, and a member of the Ridge Party was murdered. The Ridges responded by eventually forming their own council, representing only a fraction of the Cherokee people. This split the Cherokee Nation into two factions: The Western Cherokees, led by Major Ridge; and the Eastern faction, who continued to recognize Chief John Ross as head of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1835, Jackson appointed Reverend John F. Schermerhorn as a treaty commissioner. The U.S. government proposed to pay the Cherokee Nation 4.5 million dollars (among other considerations) to remove themselves. These terms were rejected in October 1835, by the Cherokee Nation council. Chief Ross, attempting to bridge the gap between his administration and the Ridge Party, traveled to Washington with John Ridge to open new negotiations, but they were turned away and told to deal with Schermerhorn.

Meanwhile, Schermerhorn organized a meeting with the pro-removal council members at New Echota, Georgia. Only five hundred Cherokees (out of thousands) responded to the summons, and on December 30, 1835, twenty-one proponents of Cherokee removal, among them Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot, signed or left "X" marks on the Treaty of New Echota. John Ridge and Stand Watie signed the treaty when it was brought to Washington. Chief Ross, as expected, refused. The signatories were violating a Cherokee Nation law drafted by John Ridge (passed in 1829), which had made it a crime to sign away Cherokee lands, the punishment for which was death.

Not a single official of the Cherokee Council signed the document. This treaty relinquished all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River. Despite the protests of the Cherokee National Council and principal Chief Ross that the document was a fraud, Congress ratified the treaty on May 23, 1836, by just one vote. A number of Cherokees (including the Ridge party) left for the West at this time, joining those who had already emigrated. By the end of 1836, more than 6,000 Cherokees had moved to the West. More than 16,000 remained in the South, however; the terms of the treaty gave them two years to leave.

Worcester v. Georgia

While frequently frowned upon in the North, the Removal Act was popular in the South, where population growth and the discovery of gold on Cherokee land had increased pressure on tribal lands. The state of Georgia became involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokees, culminating in the 1832 U.S. Supreme Court decision Worcester v. Georgia. The landmark decision determined that Cherokee Native Americans were entitled to federal protection from any state government's infringement on the tribe's sovereignty. Chief Justice John Marshall held that "the Cherokee nationâŚis a distinct communityâŚin which the laws of Georgia can have no force."[3]

Forced removal

The protests against the Treaty of New Echota continued. In the spring of 1838, Chief Ross presented a petition with more than 15,000 Cherokee signatures, asking Congress to invalidate the treaty. Many white Americans were similarly outraged by the dubious legality of the treaty and called on the government not to force the Cherokees to move. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for instance, authored a 1838 letter to Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, urging him not to inflict "so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation."[4]

Nevertheless, as the May 23, 1838, deadline for voluntary removal approached, President Van Buren assigned General Winfield Scott to head the forcible removal operation. He arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838, in command of about 7,000 soldiers. They began rounding up Cherokees in Georgia on May 26, 1838; ten days later, operations began in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama. About 17,000 Cherokeesâalong with approximately 2,000 black slaves owned by wealthy Cherokeesâwere removed at gunpoint from their homes over three weeks and gathered together in camps, often with only the clothes on their backs. They were then transferred to departure points at Ross's Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee) and Gunter's Landing (Guntersville, Alabama) on the Tennessee River, and at Fort Cass (Charleston, Tennessee) near the Cherokee Agency on the Hiwassee River (Calhoun, Tennessee). From there, they were sent to the Indian Territory, mostly traveling on foot or by some combination of horse, wagon, and boat, a distance of around 1,200 miles (1,900 km) along one of the three routes.[5]

The camps were plagued by dysentery and other illnesses, which led to many deaths. After three groups had been sent on the trail, a group of Cherokees petitioned General Scott to delay until the weather cooled, in order to make the journey less hazardous. This was granted; meanwhile Chief Ross, finally accepting defeat, managed to have the remainder of the removal turned over to the supervision of the Cherokee Council. Although there were some objections within the U.S. government because of the additional cost, General Scott awarded a contract for removing the remaining 11,000 Cherokees to Chief Ross. The Cherokee-administered marches began on August 28, 1838, and consisted of thirteen groups with an average of 1,000 people in each. Although this arrangement was an improvement for all concerned, disease still took many lives.

The number of people who died as a result of the Trail of Tears has been variously estimated. American doctor and missionary Elizur Butler, who made the journey with one party, estimated 2,000 deaths in the camps and 2,000 on the trail; his total of 4,000 deaths remains the most cited figure. A scholarly demographic study in 1973, estimated 2,000 total deaths; another, in 1984, concluded that a total of 8,000 people died.[6]

During the journey, it is said that the people would sing "Amazing Grace" to improve morale. The traditional Christian hymn had previously been translated into Cherokee by the missionary Samuel Worcester with Cherokee assistance. The song has since become a sort of anthem for the Cherokee people.[7]

Aftermath

The Cherokees who were removed initially settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The political turmoil resulting from the Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears led to the assassinations of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot; of the leaders of the Treaty Party, only Stand Watie eluded his assassins. The population of the Cherokee Nation eventually rebounded, and today the Cherokees are the largest American Indian group in the United States.

There were some exceptions to removal. Perhaps 1,000 Cherokees evaded the U.S. soldiers and lived off the land in Georgia and other states. Those Cherokees who lived on private, individually owned lands (rather than communally owned tribal land) were not subject to removal. In North Carolina, about 400 Cherokees lived on land in the Great Smoky Mountains owned by a white man named William Holland Thomas (who had been adopted by Cherokees as a boy), and were thus not subject to removal. These North Carolina Cherokees became the Eastern Band Cherokee.

The Trail of Tears is generally considered to be one of the most regrettable episodes in American history. To commemorate the event, the U.S. Congress designated the Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail in 1987. It stretches for 2,200 miles (3,540 km) across nine states.

In 2004, Senator Sam Brownback (Republican of Kansas) introduced a joint resolution (Senate Joint Resolution 37) to "offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States" for past "ill-conceived policies by the United States Government regarding Indian Tribes." The United States Senate has yet to take action on the measure.

Notes

- â PBS Online, The Trail of Tears. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- â Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars (New York: Viking, 2001). ISBN 9780670910250

- â William M. Osborn, The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During the American-Indian War From Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee (New York: Random House, 2000). ISBN 9780375503740

- â Ralph Waldo Emerson, Letter to President Martin van Buren. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- â Osborn, 177.

- â John Ehle, Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation (New York: Doubleday, 1988). ISBN 9780385239530

- â Steve Turner, Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song (New York: Harper Collins, 2003).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, William L., ed. Cherokee Removal: Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991. ISBN 082031482X

- Carter, Samuel. Cherokee Sunset: A Nation Betrayed. NY: Doubleday, 1976. ISBN 0-385-06735-6

- Duvall, Deborah L. Tahlequah: The Cherokee Nation. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-7385-0782-2

- Ehle, John. Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. New York: Doubleday, 1988. ISBN 0-385-23953-X

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Letter to President Martin van Buren. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, [1932] 1972. ISBN 0-8061-1172-0

- Osborn, William M. The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During the American-Indian War From Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee'. New York: Random House, 2000.

- PBS Online. The Trail of Tears. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995. ISBN 0803287348

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars. New York: Viking, 2001. ISBN 0-670-91025-2

- Swiderski, Richard M. The Metamorphosis of English: Versions of Other Languages. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1996. ISBN 0897894685

- Turner, Steve. Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song. New York: Harper Collins, 2003. ISBN 0-06-000218-2

- Wallace, Anthony F.C. The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993. ISBN 0-8090-1552-8

External links

All links retrieved May 1, 2023.

- Winfield Scott's Address to the Cherokee Nation, May 10, 1838

- Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail

- Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride a yearly event which claims to be "the largest annual motorcycle ride in America," raises funds for college scholarships for Native American students

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.