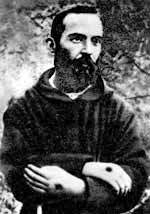

Pio of Pietrelcina

| Saint Pio of Pietrelcina | |

|---|---|

| Confessor | |

| Born | May 25, 1887 in Pietrelcina, Italy |

| Died | September 23, 1968 aged 81 in San Giovanni Rotondo |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | May 2, 1999, Rome, Italy |

| Canonized | June 16, 2002, Rome, Italy |

| Major shrine | San Giovanni Rotondo (where he lived and is now buried) |

| Feast | September 23 |

| Patronage | civil defense volunteers, Catholic adolescents, unofficial patron of stress relief and New Year Blues |

Pio of Pietrelcina (May 25, 1887 – September 23, 1968) was a Capuchin priest from Italy who is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church. He was born Francesco Forgione, and given the name Pio when he joined the Franciscan derived Capuchin Order; he was popularly known as Padre Pio (Father Pio) after his ordination to the priesthood.

Pio is renowned among Roman Catholics as one of the Church's modern stigmatists. His wounds were examined by many people, including physicians, who claimed they were authentic. This friar became famous for other alleged spiritual abilities as well including the gifts of healing, bilocation, levitation, prophecy, miracles, extraordinary abstinence from both sleep and nourishment.

Early life

Francesco Forgione was born to Grazio Mario Forgione (1860–1946) and Maria Giuseppa de Nunzio Forgione (1859–1929) on May 25, 1887 in Pietrelcina, a farming town in the Southern Italian region of Campania.[1] His parents made a living as peasant farmers.[2] He was baptized in the nearby Santa Anna Chapel, which stands upon the walls of a castle. He later served as an altar boy in this same chapel. His siblings were an older brother, Michele, and three younger sisters: Felicita, Pellegrina, and Grazia (who was later to become a Bridgettine nun).[2] His parents had two other children who died in infancy.[1] When he was baptized, he was given the name Francesco, which was the name of one of these two. He claimed that by the time he was five years old he had already taken the decision to dedicate his entire life to God.[1] He is also said to have begun inflicting penances on himself and to have been chided on one occasion by his mother for using a stone as a pillow and sleeping on the stone floor. He worked on the land up to the age of 10, looking after the small flock of sheep the family owned.[3] This delayed his education to some extent.

Pietrelcina was a highly religious town (feast days of saints were celebrated throughout the year), and religion had a profound influence on the Forgione family. The members of the family attended Daily Mass, prayed the Rosary nightly, and abstained from meat three days a week in honor of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Although Francesco's parents and grandparents were illiterate; they memorized the Scriptures and narrated Bible stories to their children. It is claimed by his mother that Francesco was able to see and speak with Jesus, the Virgin Mary and his Guardian Angel, and that as a child, he assumed that all people could do so.[4]

As a youth, he claimed to have experienced heavenly visions and ecstasies.[1] In 1897, after he had completed three years at the public school, Francesco was drawn to the life of a friar after listening to a young Capuchin friar who was, at that time, seeking donations in the countryside. When he expressed his desire to his parents, they made a trip to Morcone, a community 13 miles (21 km) north of Pietrelcina, to find out if their son was eligible to enter the Capuchin Order. The monks there informed them that they were interested in accepting Francesco into their community, but he needed more education qualifications.

Francesco's father went to the United States in search of work to pay for private tutoring for his son Francesco so that he might meet the academic requirements to enter the Capuchin Order.[3][1] It was in this period that Francesco took his Confirmation on September 27, 1899. He underwent private tutoring and passed the stipulated academic requirements. On January 6, 1903, at the age of 15, he entered the novitiate of the Capuchin Friars at Morcone, where on January 22 he took the Franciscan habit and the name of Fra (Brother) Pio in honor of Pope Saint Pius V, the patron saint of Pietrelcina. He took the simple vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.[1]

Priesthood

To commence his six-year study for priesthood and to grow in community life, he traveled to the friary of St. Francis of Assisi by oxcart. Three years later on January 27, 1907 he made his solemn profession. In 1910, Brother Pio was ordained a priest by Archbishop Paolo Schinosi at the Cathedral of Benevento. Four days later, he offered his first Mass at the parish church of Our Lady of the Angels. His health being precarious, he was permitted to remain with his family until early 1916 while still retaining the Capuchin habit.

On September 4, 1916, Padre Pio was ordered to return to his community life. Thus he was moved to an agricultural community, Our Lady of Grace Capuchin Friary, located in the Gargano Mountains in San Giovanni Rotondo. Along with Padre Pio, the community had seven friars. He stayed at San Giovanni Rotondo till his death, except for his military service.

When World War I started, four friars from this community were selected for military service. At that time, Padre Pio was a teacher at the Seminary and a spiritual director. When one more friar was called into service, Padre Pio was put in charge of the community. Then, in the month of August 1917, Padre Pio was also called to military service. Although not in good health, he was assigned to the 4th Platoon of the 100th Company of the Italian Medical Corps. Although hospitalized by mid-October, he was not discharged until March 1918, whereupon he returned to San Giovanni Rotondo and was assigned to work at Santa Maria degli Angeli (Our Lady of the Angels) in Pietrelcina. Later, in response to his growing reputation as a worker of miracles, his superiors assigned him to the friary of San Giovanni Rotondo.[5]

Padre Pio then became a Spiritual Director, guiding many spiritually, considering them his spiritual daughters and sons. He had five rules for spiritual growth, namely weekly confession, daily Communion, spiritual reading, meditation, and examination of conscience.

He compared weekly confession to dusting a room weekly, and recommended the performance of meditation and self-examination twice daily: once in the morning, as preparation to face the day, and once again in the evening, as retrospection. His advice on the practical application of theology he often summed up in his now famous quote, "Pray, Hope and Don’t Worry." He directed Christians to recognize God in all things and to desire above all things to do the will of God.[6]

Poor health

We know from the diary of father Agostino da San Marco in Lamis, the spiritual director of Padre Pio, that the young Francesco Forgione was afflicted with a number of illnesses. At six, he suffered from a grave gastroenteritis, which kept him bedridden for a long time. At ten, he caught typhoid fever. At 17, after completing his novitiate year in the Capuchins, brother Pio was sent to a neighboring province to begin his formative study—but he suddenly fell ill, complaining of loss of appetite, insomnia, exhaustion, fainting spells, and terrible migraines. He vomited frequently and could absorb only milk.

The hagiographers say that it was during this time, together with his physical illness, that inexplicable phenomena began to occur. According to their stories, one could hear strange noises coming from his room at night—sometimes screams or roars. During prayer, brother Pio remained in a stupor, as if he were absent. Such phenomena are frequently described in the hagiographies of saints and mystics of all time.

One of Pio's fellow brothers claims to have seen him in ecstasy, levitating above the ground.[7]

In June 1905, brother Pio's health was so weak that his superiors decided to send him to a mountain convent, in the hope that the change of air would do him some good. His health got worse, however, and doctors advised that he return to his home town. Yet, even there, his health continued to deteriorate.

In addition to his childhood illnesses, throughout his life Padre Pio suffered from "asthmatic bronchitis." He also had a large kidney stone, with frequent abdominal pains. He also suffered from a chronic gastritis, which later turned into an ulcer. He suffered from inflammations of the eye, of the nose, of the ear and of the throat, and eventually formed rhinitis and chronic otitis.

In 1917, he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, certified by a radiological exam. He was then sent home on permanent leave.

In 1925, Padre Pio was operated for an inguinal hernia, and shortly after this a large cyst formed on his neck which had to be surgically removed. Another surgery was required to remove a malignant tumor on his ear. After this operation Padre Pio was subjected to radiological treatment, which was successful, it seems, after only two treatments.[7]

In 1956, he came down with a serious case of "exsudative pleuritis." The diagnosis was certified by professor Cataldo Cassano, who personally extracted the serous liquid from the body of Padre Pio. He remained bedridden for four consecutive months.

In his old age Padre Pio was afflicted by arthritis.

Spiritual suffering and diabolical attacks

Padre Pio believed that the love of God was inseparable from suffering and that suffering all things for the sake of God was the way for the soul to reach God.[3] He felt that his soul was lost in a chaotic maze, plunged into total desolation, as if he were in the deepest pit of hell. During his period of spiritual suffering, his followers believe that Padre Pio was attacked by the Devil, both physically and spiritually.[3] His followers also believe that the devil used diabolical tricks in order to increase Padre Pio's torments. These included apparitions as an "angel of light" and the alteration or destruction of letters to and from his spiritual directors. Padre Augustine confirmed this when he said: "The Devil appeared as young girls that danced naked, as a crucifix, as a young friend of the monks, as the Spiritual Father or as the Provincial Father; as Pope Pius X, a Guardian Angel, as St. Francis and as Our Lady."[8]

In a letter to Padre Agostino dated February 13, 1913, Padre Pio writes: "Now, twenty-two days have passed, since Jesus allowed the devils to vent their anger on me. My Father, my whole body is bruised from the beatings that I have received to the present time by our enemies. Several times, they have even torn off my shirt so that they could strike my exposed flesh."[8]

Fr. Gabriele Amorth, senior exorcist of Vatican City stated in an interview that Padre Pio was able to distinguish between real apparitions of Jesus, Mary and the Saints and the illusions created by the Devil by carefully analysing the state of his mind and the feelings produced in him during the apparitions. In one of Padre Pio's Letters, he states that he remained patient in the midst of his trials because of his firm belief that Jesus, Mary, his Guardian Angel, St. Joseph, and St. Francis were always with him and helped him always.[8]

Transverberation and visible stigmata

Based on Padre Pio's correspondence, even early in his priesthood he experienced less obvious indications of the visible stigmata for which he would later become famous. In a 1911 letter, Padre Pio wrote to his spiritual advisor, Padre Benedetto from San Marco in Lamis, describing something he had been experiencing for a year:

Then last night something happened which I can neither explain nor understand. In the middle of the palms of my hands a red mark appeared, about the size of a penny, accompanied by acute pain in the middle of the red marks. The pain was more pronounced in the middle of the left hand, so much so that I can still feel it. Also under my feet I can feel some pain.[9]

His close friend Padre Agostino wrote to him in 1915, asking specific questions such as when he first experienced visions, whether he had been granted the stigmata, and whether he felt the pains of the Passion of Christ, namely the crowning of thorns and the scourging. Padre Pio replied that he had been favored with visions since his novitiate period (1903 to 1904). He wrote that although he had been granted the stigmata, he had been so terrified by the phenomenon he begged the Lord to withdraw them. He did not wish the pain to be removed, only the visible wounds, since, at the time he considered them to be an indescribable and almost unbearable humiliation. The visible wounds disappeared at that point, but reappeared in September 1918. He reported, however, that the pain remained and was more acute on specific days and under certain circumstances. He also said that he was indeed experiencing the pain of the crown of thorns and the scourging. He was not able to clearly indicate the frequency of this experience, but said that he had been suffering from them at least once weekly for some years.[10]

These experiences are alleged to have caused his health to fail, for which reason he was permitted to stay at home. To maintain his religious life of a friar while away from the community, he said Mass daily and taught at school.

During World War I, Pope Benedict XV who had termed the World War as "the suicide of Europe" appealed to all Christians urging them to pray for an end to the war. On July 27, 1918, Padre Pio offered himself as a victim for the end of the war. Days passed and between August 5 and August 7, Padre Pio had a vision in which Christ appeared and pierced his side.[2] As a result of this experience, Padre Pio had a physical wound in his side. This occurrence is considered as a "transverberation" or piercing of the heart indicating the union of love with God.

With his transverberation began another seven-week long period of spiritual unrest for Padre Pio. One of his Capuchin brothers said this of his state during that period: "During this time his entire appearance looked altered as if he had died. He was constantly weeping and sighing, saying that God had forsaken him."[2]

In a letter from Padre Pio to Padre Benedetto, dated August 21, 1918 Padre Pio writes of his experiences during the transverberation:

While I was hearing the boys’ confessions on the evening of the 5th [August] I was suddenly terrorized by the sight of a celestial person who presented himself to my mind’s eye. He had in his hand a sort of weapon like a very long sharp-pointed steel blade which seemed to emit fire. At the very instant that I saw all this, I saw that person hurl the weapon into my soul with all his might. I cried out with difficulty and felt I was dying. I asked the boy to leave because I felt ill and no longer had the strength to continue. This agony lasted uninterruptedly until the morning of the 7th. I cannot tell you how much I suffered during this period of anguish. Even my entrails were torn and ruptured by the weapon, and nothing was spared. From that day on I have been mortally wounded. I feel in the depths of my soul a wound that is always open and which causes me continual agony.[11]

On September 20, 1918, accounts state that the pains of the transverberation had ceased and Padre Pio was in "profound peace".[2] On that day, as Padre Pio was engaged in prayer in the choir loft in the Church of Our Lady of Grace, the same Being who had appeared to him and given him the transverberation—and who is believed to be the Wounded Christ—appeared again and Padre Pio had another experience of religious ecstasy. When the ecstasy ended, Padre Pio had received the Visible Stigmata, the five wounds of Christ. This time, however, the stigmata was permanent and would stay on him for the next fifty years of his earthly life.[2]

In a letter from St. Padre Pio to Padre Benedetto, his superior and spiritual advisor, dated October 22, 1918, Padre Pio describes his experience of receiving the Stigmata as follows:

On the morning of the 20th of last month, in the choir, after I had celebrated Mass I yielded to a drowsiness similar to a sweet sleep. [...] I saw before me a mysterious person similar to the one I had seen on the evening of 5 August. The only difference was that his hands and feet and side were dripping blood. This sight terrified me and what I felt at that moment is indescribable. I thought I should have died if the Lord had not intervened and strengthened my heart which was about to burst out of my chest. The vision disappeared and I became aware that my hands, feet and side were dripping blood. Imagine the agony I experienced and continue to experience almost every day. The heart wound bleeds continually, especially from Thursday evening until Saturday. Dear Father, I am dying of pain because of the wounds and the resulting embarrassment I feel deep in my soul. I am afraid I shall bleed to death if the Lord does not hear my heartfelt supplication to relieve me of this condition. Will Jesus, who is so good, grant me this grace? Will he at least free me from the embarrassment caused by these outward signs? I will raise my voice and will not stop imploring him until in his mercy he takes away, not the wound or the pain, which is impossible since I wish to be inebriated with pain, but these outward signs which cause me such embarrassment and unbearable humiliation.[11]

Though Padre Pio would have preferred to suffer in secret, by early 1919, news about the stigmatic friar began to spread in the secular world. Padre Pio’s wounds were examined by many people, including physicians.[2] People who had started rebuilding their lives after World War I began to see in Padre Pio a symbol of hope. Those close to him attest that he began to manifest several spiritual gifts including the gifts of healing, bilocation, levitation, prophecy, miracles, extraordinary abstinence from both sleep and nourishment (One account states that Padre Agostino recorded one instance in which Padre Pio was able to subsist for at least 20 days at Verafeno on only the Eucharist without any other nourishment), the ability to read hearts, the gift of tongues, the gift of conversions, and the fragrance from his wounds.[3]

Controversies

Accusations made against Padre Pio

As Padre Pio's fame grew, his ministry began to take the center-stage at the friary. Many pilgrims flocked to see him and he spent around 19 hours each day celebrating Mass, listening to confessions and corresponding, often sleeping not even two hours per day. His fame had the negative side effect that accusations against him made their way to the Holy Office in Rome (since 1983, known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith), causing many restrictions to be placed on him. His accusers included high-ranking archbishops, bishops, theologians and physicians.[12]

Nature of the charges

They brought several accusations against him, including insanity, immoral attitude towards women—claims that he had intercourse with women in the confessional; misuse of funds, and deception—claims that the stigmata were induced with acid in order to gain fame, and that the reported odor of sanctity around him being the result of self-administered eau-de-cologne.[13]

The founder of Rome's Catholic university hospital concluded Padre Pio was "an ignorant and self-mutilating psychopath who exploited people's credulity."[13] In short, he was accused of infractions against all three of his monastic vows: poverty, chastity and obedience.[12]

In 1923, he was forbidden to teach teenage boys in the school attached to the monastery because he was considered "a noxious Socrates, capable of perverting the fragile lives and souls of boys."[14]

Home to Relieve Suffering

In 1940, Padre Pio began plans to open a hospital in San Giovanni Rotondo, to be named the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza or "Home to Relieve Suffering"; the hospital opened in 1956.[15] Barbara Ward, a British humanitarian and journalist on assignment in Italy, played a major role in obtaining for this project a grant of $325,000 from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). In order that Padre Pio might directly supervise this project, Pope Pius XII, in 1957 granted him dispensation from his vow of poverty.[16] Padre Pio's detractors used this project as another weapon to attack him, charging him with misappropriation of funds.[16]

Investigations

Padre Pio was subject to numerous investigations.[15][16] Fearing local riots, a plan to transfer Padre Pio to another friary was dropped and a second plan was aborted when a riot almost happened.[12] In the period from 1924 to 1931, the Holy See made various statements denying that the happenings in the life of Padre Pio were due to any divine cause.[15] At one point, he was prevented from publicly performing his priestly duties, such as hearing confessions and saying Mass.[15]

Papal views 1930s to 1960s

By 1933, the tide began to turn, with Pope Pius XI ordering the Holy See to reverse its ban on Padre Pio’s public celebration of Mass. The Pope said, "I have not been badly disposed toward Padre Pio, but I have been badly informed." In 1934, he was again allowed to hear confessions. He was also given honorary permission to preach despite never having taken the exam for the preaching license. Pope Pius XII, who assumed the papacy in 1939, encouraged devotees to visit Padre Pio. According to a recent book, Pope John XXIII (1958-1963) apparently did not espouse the outlook of his predecessors, and wrote in 1960 of Padre Pio’s “immense deception.”[9] However, it was John XXIII's successor, Pope Paul VI, who, in the mid 1960s, firmly dismissed all accusations against Padre Pio.[12][16]

Death

The deterioration of Padre Pio's health started during the 1960s in spite of which he continued his spiritual works. Due to Padre Pio's advanced age and deteriorating health, Pope Paul VI granted Padre Pio special permission to continue saying the Traditional Latin Mass following the institution of certain liturgical changes following the Second Vatican Council.[14]

On September 21, 1968, the day after the 50th anniversary of his receiving the Stigmata, Padre Pio experienced great tiredness.[17] The next day, on September 22, 1968 Padre Pio was supposed to offer a Solemn Mass, but feeling weak and fearing that he might be too ill to complete the Mass, he asked his superior if he might say a Low Mass instead, just as he had done daily for years. Due to the large number of pilgrims present for the Mass, Padre Pio's superior decided the Solemn Mass must proceed, and so Padre Pio, in the spirit of obedience to his superior, went on to celebrate the Solemn Mass. While celebrating the Solemn Mass, Padre Pio appeared extremely weak and in a fragile state. His voice was weak when he said the Mass, and after the Mass had concluded, he was so weakened that he almost collapsed as he was descending the altar steps and needed help from a great many of his Capuchin confreres. This would be Padre Pio's last celebration of the Mass.

Early in the morning of September 23, 1968, Padre Pio made his last confession and renewed his Franciscan vows. As was customary, he had his Rosary in his hands, though he did not have the strength to say the Hail Marys aloud.[17] At around 2:30am, he said, "I see two mothers" (taken to mean his mother and Mary).[17] At 2:30 am, he breathed his last in his cell in San Giovanni Rotondo with his last breath whispering, "Maria!"[1]

His body was buried on September 26 in a crypt in the Church of Our Lady of Grace. His funeral was attended by over 100,000 people. He was often heard to say, "After my death I will do more. My real mission will begin after my death".[17] The accounts of those who stayed with Padre Pio till the end state that the stigmata had completely disappeared without even leaving a scar. Only a red mark "as if drawn by a red pencil" remained on his side which then disappeared.[17]

Alleged supernatural phenomena

His Mass would often last hours, as the mystic received visions and experienced sufferings. Note the coverings worn on his hands to cover his stigmata. Padre Pio acquired fame as a worker, and was purported to have the gift of reading souls. He is alleged to have been able to bilocate according to eyewitness accounts.[18]

In 1947, Father Karol Józef Wojtyła, a young Polish priest who would later go on to become Pope John Paul II, visited Padre Pio who heard his confession. Although not mentioned in George Weigel's biography Witness to Hope, which contains an account of the same visit, Austrian Cardinal Alfons Stickler reported that Wojtyła confided to him that during this meeting Padre Pio told him he would one day ascend to "the highest post in the Church."[19] Cardinal Stickler further went on to say that Wojtyła believed that the prophecy was fulfilled when he became a Cardinal, not Pope, as has been reported in works of piety.[20]

Bishop Wojtyła wrote to Padre Pio in 1962 to ask him to pray for Dr. Wanda Poltawska, a friend in Poland who was thought to be suffering from cancer. Later, Dr. Poltawska's cancer was found to have regressed; medical professionals were unable to offer an explanation for the phenomenon.[21]

Due to the unusual abilities that Padre Pio allegedly possessed, the Holy See twice instituted investigations of the stories surrounding him. However, the Church has since formally approved his veneration with his canonization by Pope John Paul II in 2002.

In the 1999 book, Padre Pio: The Wonder Worker, a segment by Irish priest Malachy Gerard Carroll describes the story of Gemma de Giorgi, a Sicilian girl whose alleged blindness some believe was corrected during a visit to the Capuchin priest.[22] Gemma, who was brought to San Giovanni Rotondo in 1947 by her grandmother, was born without pupils. During her trip to see Padre Pio, the little girl reportedly began to see objects including a steamboat and the sea. Gemma's grandmother did not believe the child had been healed.[22] After Gemma forgot to ask Padre Pio for Grace during her Confession, her grandmother reportedly implored the priest to ask God to restore her sight. Padre Pio, according to Carroll, told her, "The child must not weep and neither must you for the child sees and you know she sees."[22] The section goes on to say that oculists were unable to determine how she gained vision.[22]

Padre Pio is also alleged to have waged physical combat with Satan, similar to incidents described concerning St. John Vianney, from which he is said to have sustained extensive bruising. He is also said to have possessed the ability to communicate with guardian angels, often granting favors and healings prior to any written or verbal request.

Stigmata

On September 20, 1918, while hearing confessions, Padre Pio is said to have had his first occurrence of stigmata—bodily marks, pain, and bleeding in locations corresponding to the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ. This phenomenon allegedly continued for 50 years, until the end of his life. The blood flowing from the stigmata is said to have smelled of perfume or flowers, a phenomenon mentioned in stories of the lives of several saints and often referred to as the odour of sanctity.

His stigmata, regarded by some as evidence of holiness, was studied by physicians whose independence from the Church is not known.[15][16] The observations were reportedly unexplainable and the wounds never infected.[15][16] It was reputed, however, that his condition caused him great embarrassment, and most photographs show him with red mittens or black coverings on his hands and feet where the bleedings occurred.[16]

At Padre Pio's death in 1968, his body appeared unwounded, with no sign of scarring. There was even a report that doctors who examined his body found it empty of all blood.[23] Photos taken of his bare feet and hands during his funeral procession created some scandal with allegations of stigmata fraud, although believers saw the disappearance of the marks as yet another miracle.

Accusations of fraud

Historian Sergio Luzzatto and others, both religious and non-religious, have accused Padre Pio of faking his stigmata. Luzzatto's theory, namely that Padre Pio used carbolic acid to self-inflict the wounds, is based on a document found in the Vatican's archive—the testimony of a pharmacist at the San Giovanni Rotondo, Maria De Vito, from whom he ordered 4 grams of the acid.[24] According to De Vito, Padre Pio asked her to keep the order secret, saying it was to sterilize needles. The document was examined but dismissed by the Catholic Church during Padre Pio's beatification process.[24]

One commentator expressed the belief that the Church likely dismissed the claims based on alleged evidence that the acid was in fact used for sterilization: "The boys had needed injections to fight the Spanish Flu which was raging at that time. Due to a shortage of doctors, Padres Paolino and Pio administered the shots, using carbolic acid as a sterilizing agent.”[24]

Sainthood

In 1982, the Holy See authorized the archbishop of Manfredonia to open an investigation to discover whether Padre Pio should be considered a saint. The investigation went on for seven years, and in 1990 Padre Pio was declared a Servant of God, the first step in the progression to canonization.

Beginning in 1990, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints debated how heroically Padre Pio had lived his life, and in 1997 Pope John Paul II declared him venerable. A discussion of the effects of his life on others followed, including the cure of an Italian woman, Consiglia de Martino, which had been associated with Padre Pio's intercession. In 1999, on the advice of the Congregation, John Paul II declared Padre Pio blessed.

After further consideration of Padre Pio's virtues and ability to do good even after his death, including discussion of another healing attributed to his intercession, the Pope declared Padre Pio a saint on June 16, 2002.[20] Three-hundred-thousand people were estimated to have attended the canonization ceremony.[20]

Later recognition

On July 1, 2004, Pope John Paul II dedicated the Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church in San Giovanni Rotondo to the memory of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina.[25] A statue of Saint Pio in Messina, Sicily attracted attention in 2002 when it allegedly wept tears of blood.[26] Padre Pio has become one of the world's most popular saints. There are more than 3,000 "Padre Pio Prayer Groups" worldwide, with 3 million members. There are parishes dedicated to Padre Pio in Vineland, New Jersey and Sydney, Australia.

Exhumation

On March 3, 2008 the body of Saint Pio was exhumed from his crypt, 40 years after his death, so that his remains could be prepared for display. A church statement described the body as being in "fair condition." Archbishop Domenico D'Ambrosio, papal legate to the shrine in San Giovanni Rotondo, stated "the top part of the skull is partly skeletal but the chin is perfect and the rest of the body is well preserved."[27] He further confirmed that formalin was injected into Padre Pio's body prior to burial to preserve it. He went on to say that St. Pio's hands "looked like they had just undergone a manicure." The stigmata were not visible.

It was hoped that morticians would be able to restore the face so that it will be recognizable. However, due to its deterioration, his face was covered with a life-like silicone mask. José Cardinal Saraiva Martins, prefect for the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, celebrated Mass for 15,000 devotees on April 24 at the Shrine of Holy Mary of Grace, San Giovanni Rotondo, before the body went on display in a crystal, marble, and silver sepulcher in the crypt of the monastery. 800,000 pilgrims worldwide, mostly from Italy, made reservations to view the body up to December 2008.[28]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Bernard C. Ruffin, Padre Pio: The True Story (Our Sunday Visitor, 1991, ISBN 9780879736736).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Ryan Gerhold, "The Second St. Francis" The Angelus (February 20, 2007): 12-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Joseph Pelletier, Padre Pio, Mary and the Rosary Garabandal. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ A Short Biography Padre Pio Devotions. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Padre Pio and the Veterans Saint Pio Foundation. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Diane Allen, Pray, Hope, and Don't Worry: True Stories of Padre Pio (Lightning Source Inc, 2013, ISBN 978-0983710516).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Renzo Allegri, I miracoli di Padre Pio (Mondadori, 1996, ISBN 8804413220).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 The Devil Saint Pio of Pietrelcina. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ian Fisher, Italian Saint Stirs Up a Mix of Faith and Commerce The New York Times (April 25, 2008). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Francesco Castelli, Padre Pio Under Investigation: The Secret Vatican Files (Ignatius Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1586174057).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 First-Class Relic of Padre Pio Atlas Obscura. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 John L. Allen, For all who feel put upon by the Vatican: A new patron saint of Holy Rehabilitation National Catholic Reporter (December 28, 2001). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Paul Vallely, Vatican makes a saint of the man it silenced New Zealand Herald (June 17, 2002). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Michael Bronski, The politics of sainthood The Boston Phoenix (July 18, 2002). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 The Stigmatist TIME (Deceember 19, 1949). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 A Padre's Patience TIME (April 24, 1964). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 John Schug, A Padre Pio Profile (St Bedes Pubns, 1987, ISBN 978-0932506566).

- ↑ Joan Carroll-Cruz, Mysteries, Marvels and Miracles (Tan Books, 1997, ISBN 978-0895555410).

- ↑ Jonathan Kwitny, Man of the Century: The Life and Times of Pope John Paul II (Henry Holt and Co., 1997, ISBN 978-0805026887).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Paula Zahn, Padre Pio Granted Sainthood CNN (June 17, 2002). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Frank M. Rega, Padre Pio and America (TAN Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0895558206).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Francis Mary Kalvelage (ed.), Padre Pio: The Wonder Worker (Ignatius Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0898707700).

- ↑ Padre Pio's Cell Padre Pio Foundation. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Malcolm Moore, Italy's Padre Pio 'faked his stigmata with acid' The Telegraph (October 23, 2007). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ John Hooper, Monumental church dedicated to controversial saint Padre Pio The Guardian (July 2, 2004). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Italian statue weeps blood BBC News (March 6, 2002). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Italy exhumes revered monk's body BBC News (March 3, 2008). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ↑ Malcolm Moore, Pilgrims flock to see body of Padre Pio The Telegraph (April 24, 2008). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allegri, Renzo. I miracoli di Padre Pio. Mondadori, 1996. ISBN 8804413220

- Allen, Diane. Pray, Hope, and Don't Worry: True Stories of Padre Pio. Lightning Source Inc, 2013. ISBN 978-0983710516

- Cantalamessa, Raniero. Words of Light: Inspiration From the Letters of Padre Pio. Paraclete Press, 2008. ISBN 9781557255693

- Carroll-Cruz, Joan. Mysteries, Marvels and Miracles. Tan Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0895555410

- Castelli, Francesco. Padre Pio Under Investigation: The Secret Vatican Files. Ignatius Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1586174057

- Kalvelage Francis Mary (ed.). Padre Pio: The Wonder Worker. Ignatius Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0898707700

- Kwitny, Jonathan. Man of the Century: The Life and Times of Pope John Paul II. Henry Holt and Co., 1997. ISBN 978-0805026887

- Pasquale, Gianluigi (ed.), DiFabio, Elvira G. (trans.) Secrets of a Soul: Padre Pio's Letters to His Spiritual Director. Pauline Books & Media, 2003. ISBN 9780819859471

- Rega, Frank M. Padre Pio and America. TAN Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0895558206

- Ruffin, Bernard C. Padre Pio: The True Story. Our Sunday Visitor, 1991. ISBN 9780879736736

- Schug, John. A Padre Pio Profile. St Bedes Pubns, 1987. ISBN 978-0932506566

External links

All links retrieved October 2, 2023.

- Saint Padre Pio Vatican biography

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina Franciscan Media

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina Catholic Web Services

- St. Padre Pio Catholic Online

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.