Pasupata

Pashupata Shaivism was one of the main Shaivite schools. The Pashupatas (Sanskrit: PÄÅupatas) are the oldest named Shaivite group, originating sometime between the second century B.C.E. and the second century C.E. There are accounts of the Pasupata system in the Sarvadarsanasamgraha of Madhavacarya (c. 1296â 1386) and in Advaitanandaâs Brahmavidyabharana, and Pasupata is criticized by Samkara (c. 788â820) in his commentary on the Vedanta Sutras.[1] They are also referred to in the Mahabharata. The Pasupata doctrine gave rise to two extreme schools, the Kalamukha and the Kapalika, known as Atimargika (schools away from the path), as well as a moderate sect, the Saivas (also called the Siddhanta school), which developed into modern Shaivism.

The ascetic practices adopted by the Pasupatas included smearing their bodies thrice-daily with ashes, meditation, and chanting the symbolic syllable âom.â Their monotheistic belief system enumerated five categories: Karan (cause), Karya (effect), Yoga (discipline), Vidhi (rules), and Dukhanta (end of misery). They taught that the Lord, or pati, is the eternal ruler who creates, maintains, and destroys the whole universe, and that all existence is dependent on him. Even after attaining the ultimate elevation of the spirit, individual souls retained their uniqueness.

History

Pasupata was perhaps the earliest Hindu sect that worshiped Shiva as the supreme deity, and was perhaps the oldest named Shaivite group.[2] Various sub-sects flourished in northern and northwestern India (Gujarat and Rajasthan), until at least the twelfth century, and spread to Java and Cambodia. The Pashupata movement was influential in South India in the period between the seventh and fourteenth century, when it disappeared.

The dates of the emergence of Pasupata are uncertain, and various estimates place them between the second century B.C.E. and the second century C.E. Axel Michaels dates their existence from the first century C.E.[3] Gavin Flood dates them probably from around the second century C.E.[2] There is an account of the Pasupata system in the Sarvadarsanasamgraha of Madhavacarya (1296â1386), who refers Nakulish-pashupata,Shaiva, Pratyabhijna, and Raseshvara as the four schools of Shaivism; and in Advaitanandaâs Brahmavidyabharana. Pasupata is criticized by Samkara (c. 788â820) in his commentary on the Vedanta Sutras. They are referred to in the Mahabharata.[2]

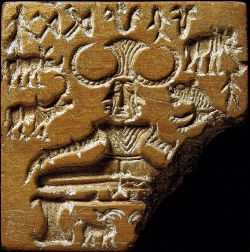

The sect takes its name from Pashupati (Sanskrit: PaÅupati, an epithet of the Hindu deity Shiva meaning Lord of Cattle,[4] which was later extended to convey the meaning âLord of Souls.â Rudra, the personification of the destructive powers of nature in the Rig Veda ( i. 114,8) became the lord of cattle, pasunam patih, in the Satarudriya, and Shiva in the Brahamanas. The Pasupata system continued in the tradition of Rudra-Shiva.

Pasupata teachings were believed to have originated with Shiva himself, reincarnated as the teacher Lakulin. According to legends found in later writings, such as the Vayu-Purana and the Linga-Purana, Shiva revealed that during the age of Lord Vishnu's appearance as Vasudeva-Krishna, he would enter a dead body and incarnate himself as Lakulin (Nakulin or Lakulisa, lakula meaning âclubâ). Inscriptions from the tenth and thirteenth centuries refer to a teacher named Lakulin, who was believed by his followers to be an incarnation of Shiva.

The ascetic practices adopted by the Pasupatas included smearing their bodies thrice-daily with ashes, meditation, and chanting the symbolic syllable âom.â The Pasupata doctrine gave rise to the development of two extreme schools, the Kalamukha and the Kapalika, as well as a moderate sect, the Saivas (also called the Siddhanta school). The Pasupatas and the extreme sects became known as Atimargika (schools away from the path), distinct from the more moderate Saiva, the origin of modern Saivism.

Belief system

The monotheistic system of Pasupata, described in the epic Mahabharata, consisted of five main categories:

- Karan (Cause), the Lord or pati, the eternal ruler, who creates, maintains, and destroys the whole existence.

- Karya (Effect), all that is dependent on the cause, including knowledge (vidya), organs (kala), and individual souls (pasu). All knowledge and existence, the five elements and the five organs of action, and the three internal organs of intelligence, egoism and mind, are dependent on the Lord

- Yoga ( Discipline), the mental process by which the soul gains God.

- Vidhi (Rules), the physical practice of which generates righteousness

- Dukhanta (End of misery), the final deliverance or destruction of misery, and attainment of an elevation of the spirit, with full powers of knowledge and action. Even in this ultimate condition, the individual soul has its uniqueness, and can assume a variety of shapes and do anything instantly.

Prasastapada, the early commentator on the Vaisesika Sutras and Uddyotakara, the author of gloss on the Nyaya Bhasa, were followers of this system.

Kapalika and Kalamukha

Kapalika and Kalamukha were two extreme schools which developed from Pasupata doctrine. Kalamukha, Sanskrit for "Black-faced," probably referred to a black mark of renunciation worn on the forehead. The Kalamukha sect issued from Pashupata Saivism at its height (c. 600-1000). No Kalamukha religious texts exist today; this sect is known only indirectly. Inscriptions at the Kedareshvara Temple (1162) in Karnataka, which belonged to the Kalamukha sect, are an important source of information.

The Kalamukha, practitioners of Buddhist Tantra, were said to be well organized in temple construction and worship, as well as eccentric and unsocial, eating from human skulls, smearing their bodies with ashes from the cremation ground, carrying clubs, and wearing matted hair.[5]

The Kalamukhas were closely related to the Kapalikas. In Hindu culture, "Kapalika" means "bearer of the skull-bowl," in reference to Lord Bhairava's vow to take the kapala vow. As penance for cutting off one of the heads of Brahma, Lord Bhairava became an outcast and a beggar. In this guise, Bhairava frequents waste places and cremation grounds, wearing nothing but a garland of skulls and ash from the pyre, and unable to remove the skull of Brahma fastened to his hand. The skull hence becomes his begging-bowl, and the Kapalikas (as well as the Aghoris of Varanasi) supposedly used skulls as begging bowls and as drinking and eating vessels in imitation of Shiva. Although information on the Kapalikas is primarily found in classical Sanskrit sources, where Kapalika ascetics are often depicted as depraved villains in drama, it appears that this group worshiped Lord Shiva in his extreme form, Bhairava, the ferocious. They are also often accused of having practiced ritual human sacrifices. Ujjain is alleged to have been a prominent center of this sect.

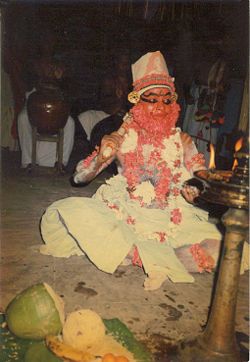

In modern Tamilnadu, certain Shaivite cults associated with the goddesses Ankalaparamecuvari, Irulappasami, and Sudalai Madan, are known to practice or have practiced, ritual cannibalism, and to center their secretive rituals around an object known as a kapparai (Tamil "skull-bowl," derived from the Sanskrit kapala), a votive device garlanded with flowers and sometimes adorned with faces, which is understood to represent the begging-bowl of Shiva.

Notes

- â S. Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1948).

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gavin D. Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- â Axel Michaels and Barbara Harshav, Hinduism Past and Present (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

- â Rama Karana ÅarmÄ, ÅivasahasranÄmÄá¹£á¹akam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Åiva (Delhi: Nag Publishers, 1996).

- â David N. Lorenzen, Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects (Berkeley: University of California Press, 197, ISBN 0520018427).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Flood, Gavin D. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 2003. ISBN 1405123060

- Flood, Gavin D. An Introduction to Hinduism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521433045

- Lorenzen, David N. Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972. ISBN 0520018427

- Michaels, Axel, and Barbara Harshav. Hinduism Past and Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 0691089523

- Radhakrishnan, S. Indian philosophy. Vol. I. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1948.

- ÅarmÄ, RÄma Karaá¹a. ÅivasahasranÄmÄá¹£á¹akam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Åiva. Delhi: Nag Publishers, 1996. ISBN 8170813506

- Sharma, Chandrahar. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2003. ISBN 8120803647

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.