Backgammon

Backgammon is a two-player board game played with counters and dice on a tables board. It is the most widespread Western member of the large family of tables games, whose ancestors date back nearly 5,000 years. The earliest record of backgammon itself dates to seventeenth-century England, being descended from the sixteenth-century game of Irish.

Backgammon is a two-player game of contrary movement in which each player has fifteen pieces known traditionally as men (short for 'tablemen'). The backgammon table pieces move along twenty-four 'points' according to the roll of two dice. The objective of the game is to move the fifteen pieces around the board and be first to bear off, i.e., remove them from the board. The achievement of this while the opponent is still a long way behind results in a triple win known as a backgammon, hence the name of the game.

Backgammon involves a combination of strategy and luck from rolling dice. With each roll of the dice, players must choose from numerous options for moving their pieces and anticipate possible counter-moves by the opponent. While the dice may determine the outcome of a single game, the better player will accumulate a winning record over a series of many games.

History

Backgammon is a recent member of the large family of tables games that date back to ancient times. Its equipment is similar or identical to earlier tables games that have been depicted for centuries in art, leading to the mistaken belief that backgammon itself is much older.

The earliest specific reference to backgammon is from the seventeenth century, and by the nineteenth century backgammon had spread in Europe, where it rapidly superseded other tables games like Trictrac in popularity.

Precursors

Precursors of backgammon can be traced back nearly 5,000 years to archaeological discoveries of the Jiroft culture, located in present-day Iran. The world's oldest game set having been discovered in the region with equipment comprising a dumbbell-shaped board, counters, and dice. The game dates roughly to the period from 1500 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E. and is known to have been played in the region that includes Babylon, Mesopotamia, and Persia, as well as Egypt.

Although its precise rules are unknown, it has been termed the Game of 20 Squares.[2] The board comprises two distinct sections; a quadrant of 3 × 4 squares, and a row or 'arm' of 8 squares projecting from the central row of the quadrant. It has five rosettes. The rules are not precisely known but it appears likely that players entered all their 5 pieces onto the arm and aimed to bear them off from the sides of the quadrant, perhaps having contested the arm by hitting opposing pieces off.[3] Egyptian gaming boxes often have a board for this game on the opposite side to that for the better-known game of senet.

Similar to the Game of 20 Squares, the Royal Game of Ur from 2600 B.C.E. may also be an ancestor or intermediate of modern-day table games like backgammon. It is the oldest game for which rules have been handed down. It used tetrahedral dice. Various other board games spanning the tenth to seventh centuries B.C.E. have been found throughout modern day Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and western Iran.[2][4]

The Persian tables game of "nard" or "nardšir" emerged somewhere between the third and sixth century C.E., one text (Kār-nāmag ī Ardaxšēr ī Pāpakān) linking it with Ardashir I (r. 224–241), founder of the Sasanian dynasty, whereas another (Wičārišn ī čatrang ud nihišn ī nēw-ardaxšēr) attributes it to Bozorgmehr Bokhtagan, the Vizier of Khosrow (r. 531–579), who is credited with the invention of the game. The Shahnameh (written around the year 1000) also attributes the invention to Bozorgmehr.[5] Parlett refers to Nard as "proto-Backgammon."[3]

The earliest identifiable tables game, Tabula, meaning "table" or "board," is described in an epigram of Byzantine Emperor Zeno (476–491 C.E.).[6] The board had the typical tables layout, with 24 points, 12 on each side; and there were 15 counters per player; the overall aim was to be first to bear one's pieces off. However, unlike modern Western backgammon, there were three cubical dice not two, no bar nor doubling die, and all counters started off the board.[6] Modern backgammon follows the same rules as tabula for hitting a blot and for bearing off; and the rules for re-entering pieces in backgammon are the same as those for initially entering pieces in tabula.[7] The name Tavli (τάβλι) is still used in Greece for various tables games.

The Tavli of Emperor Zeno's time is believed to be a direct descendant of the earlier Roman ludus duodecim scriptorum ('Game of twelve lines') with the board's middle row of points removed, and only the two outer rows remaining.[8] Ludus duodecim scriptorum used a board with three rows of 12 points each, with the 15 pieces being moved in opposing directions by the two players across three rows according to the roll of the three cubical dice.[6] Little specific text about the gameplay of Ludus duodecim scriptorum has survived. The earliest known mention of the game is in Ovid's Ars Amatoria ('The Art of Love'), written between 1 B.C.E. and 8 C.E. In Roman times, this game was also known as alea.[2]

Tables games first appeared in France during the eleventh century and became a favorite pastime of gamblers. In 1254, Louis IX issued a decree prohibiting his court officials and subjects from playing.[9] They were played in Germany in the twelfth century, and had reached Iceland by the thirteenth century. In Spain, the Alfonso X manuscript Libro de los Juegos (Spanish: "Book of games"), completed in 1283, describes rules for dice and table games in addition to its discussion of chess.[10] By the seventeenth century, games at tables had spread to Sweden. A wooden board and counters were recovered from the wreck of the Vasa among the belongings of the ship's officers. Tables games appear widely in paintings of this period, mainly those of Dutch and German painters, such as van Ostade, Jan Steen, Hieronymus Bosch, and Bruegel. Among surviving artworks are Cardsharps by Caravaggio.

Early backgammon

Backgammon's immediate predecessor was the sixteenth century tables game of Irish.[11] Irish was the Anglo-Scottish equivalent of the French Toutes Tables and Spanish Todas Tablas, the latter name first being used in the 1283 El Libro de los Juegos, a translation of Arabic manuscripts by the Toledo School of Translators. Irish had been popular at the Scottish court of James IV and considered to be "the more serious and solid game" when the variant which became known as Backgammon began to emerge in the first half of the seventeenth century. In medieval Italy, Barail was played on a backgammon board, with the important difference that both players moved their pieces counter-clockwise and starting from the same side of the board.[9]

The earliest mention of backgammon, under the name Baggammon, was by James Howell in a letter dated 1635.[12] In English, the word "backgammon" is most likely derived from "back" and Middle English gamen meaning "game" or "play." In 1666, it is reported that the "old name for backgammon used by Shakespeare and others" was Tables.[13] However, it is clear from Willughby that "tables" was a generic name and that the phrase "playing at tables" was used in a similar way to "playing at cards."[11] The first known rules of "Back Gammon" were produced by Francis Willoughby around 1672;[11] they were quickly followed by Charles Cotton in 1674.[14]

In the sixteenth century, Elizabethan laws and church regulations had prohibited "playing at tables" in England, but by the eighteenth century, Backgammon had superseded Irish and become popular among the English clergy.[9] Edmond Hoyle published A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-Gammon in 1753; this described rules and strategy for the game and was bound together with a similar text on whist.[15]

The early form of backgammon was very similar to its predecessor, Irish. The aim, board, number of pieces or "men", direction of play and starting layout were the same as in the modern game. Charles Cotton (1674) gives an alternative starting layout as well as the familiar one. However, there was no doubling die, there was no bar on the board or the bar was not used (men simply being moved off the table when hit) and the scoring was different. The game was won double if either the winning throw was a doublet or the opponent still had men outside the home board. It was won triple if a player bore all men off before any of the opponent's men reached the home board; this was a back-gammon. Some terminology, such as "point", "hitting a blot", "home", "doublet", "bear off" and "men" are recognizably the same as in the modern game; others, such as "binding a man" (adding a second man to a point) "binding up the tables" (taking all one's first 6 points), "fore game", "latter game", "nipping a man" (hitting a blot and playing it on forwards) "playing at length" (using both dice to move one man) are no longer in vogue.[14][11]

Modern backgammon

By no later than 1850, the rules of play had changed to those used today. Tables boards were now made with a "bar" in the center and men that were hit went onto the bar. Winning double or by "two hits" was achieved by bearing all one's men off before the other has borne any; this was now called a gammon. If the winner bore off all men while the loser still had men in his adversary's table, it was a back-gammon and worth "three hits", or triple.[16]

The most recent major development in backgammon was the addition of the doubling cube. This was first introduced in the 1920s in New York City among members of gaming clubs in the Lower East Side. The cube required players not only to select the best move in a given position, but also to estimate the probability of winning from that position, transforming backgammon into the expected value-driven game played in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[17]

The popularity of backgammon surged in the mid-1960s, in part due to the charisma of Prince Alexis Obolensky who became known as "The Father of Modern Backgammon."[18] "Obe," as he was called by friends, co-founded the International Backgammon Association, which published a set of official rules. He also established the World Backgammon Club of Manhattan, devised a backgammon tournament system in 1963, then organized the first major international backgammon tournament in March 1964, which attracted royalty, celebrities and the press.[19] The game became a huge fad and was played on college campuses, in discothèques and at country clubs.[18] Stockbrokers and bankers began playing at conservative men's clubs:

A disk and dice game that has been played in Middle Eastern streets for thousands of years, in English homes for hundreds of years, and on Bronx stoops for dozens of years has suddenly gripped the bankers and brokers of old-line men's clubs all over town.[20]

People young and old all across the country dusted off their boards and pieces. Backgammon clubs were formed and tournaments were held. A series of international tournaments resulted in the official World Championships in Backgammon played annually.[21]

In the second half of the twentieth century, new terms were introduced in America, such as "beaver" and "checkers" for the "men" (although American backgammon experts Jacoby and Crawford continued to use both the older terms as well as the new ones).[22] The United States Backgammon Federation (USBGF) was organized in 2009 to repopularize the game in the United States. Board and committee members include many of the top players, tournament directors and writers in the worldwide backgammon community.

The UK Backgammon Federation is the national authority in the UK, running a backgammon championship, the Backgammon Galaxy UK Open Tournament, as well as club championships, online leagues, and knockout tournaments. Like the USBGF they are active members of the World Backgammon Federation (WBF).

Eastern Mediterranean

Backgammon is considered the national game in many countries of the Eastern Mediterranean: "While other games—chess, bridge, even poker—have made inroads from time to time, backgammon has been for centuries the pastime of the Middle East."[23] The popularity of the game across the region is primarily an oral tradition and appears to have been strengthened during the era of the Ottoman Empire, which controlled the whole Eastern Mediterranean in the early modern period. Afif Bahnassi, Syria's director of antiquities, stated in 1988: "For some reason, backgammon became the rage of the Ottoman Empire. It really spread across the Arab world with the Turks, and it stayed behind when they left."[23] The game is a common feature of coffeehouses throughout the region. Since at least the early nineteenth century, Damascus became well known as the preeminent location for Damascene-style wooden marquetry backgammon sets that have become famous throughout the region.[23]

A unique feature of backgammon throughout the region is players' use of mixed Persian and Turkish numbers to announce dice rolls, rather than Arabic or other local languages. Related to this phenomenon, the game is frequently referred to as Shesh Besh, which is a rhyming combination shesh, meaning six in Persian (as well as many historical and current Iranian languages), and besh, meaning five in Turkish. Shesh besh is commonly used to refer to when a player scores a 5 and 6 at the same time on dice.[24]

Rules

Since 2018, backgammon has been overseen internationally by the World Backgammon Federation who set the rules of play for international tournaments.

Backgammon playing pieces may be termed "men" (short for "tablemen"), checkers, draughts, stones, counters, pawns, discs, pips, chips, or nips.[25] Checkers is a relatively modern American English term derived from another board game, draughts, which in US English is called checkers.

The objective is for players to bear off all their disc pieces from the board before their opponent can do the same. As the playing time for each individual game is short, it is often played in matches where victory is awarded to the first player to reach a certain number of points.

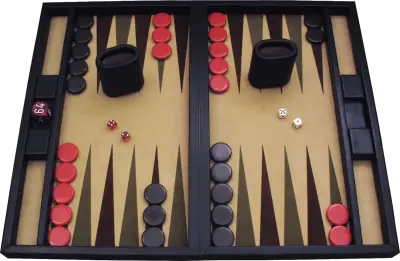

Board

The dimensions of a board when opened, for a tournament game, should be between 37 and 50 millimeters in diameter.[26]

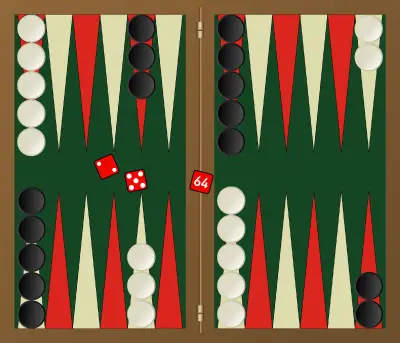

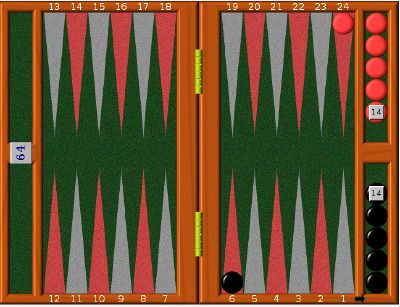

Setup

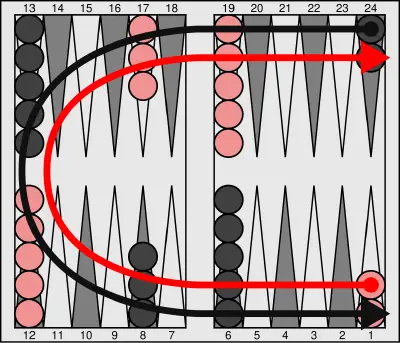

Each side of the board has a track of 12 long triangles, called points. The points form a continuous track in the shape of a horseshoe, and are numbered from 1 to 24. In the most commonly used setup, each player begins with fifteen pieces; two are placed on their 24-point, three on their 8-point, and five each on their 13-point and their 6-point. The two players move their pieces in opposing directions, from the 24-point towards the 1-point.[27]

Points 1 through 6 are called the home board or inner board, and points 7 through 12 are called the outer board. The 7-point is referred to as the bar point, and the 13-point as the midpoint. The 5-point for each player is sometimes called the "golden point."[28]

Movement

To start the game, each player rolls one die, and the player with the higher number moves first using the numbers shown on both dice. If the players roll the same number, they must roll again until they roll different numbers.[29] Both dice must land completely flat on the right-hand side of the gameboard. The players then take alternate turns, rolling two dice at the beginning of each turn.[28]

After rolling the dice, players must, if possible, move their pieces according to the number shown on each die. For example, if the player rolls a 6 and a 3 (denoted as "6-3"), the player must move one checker six points forward, and another or the same checker three points forward. The same checker may be moved twice, as long as the two moves can be made separately and legally: six and then three, or three and then six. If a player rolls two of the same number, called doubles, that player must play each die twice. For example, a roll of 5-5 allows the player to make four moves of five spaces each. On any roll, a player must move according to the numbers on both dice if it is at all possible to do so. If one or both numbers do not allow a legal move, the player forfeits that portion of the roll and the turn ends. If moves can be made according to either one die or the other, but not both, the higher number must be used. If one die is unable to be moved, but such a move is made possible by the moving of the other die, that move is compulsory.

In the course of a move, a checker may land on any point that is unoccupied or is occupied by one or more of the player's own checkers. It may also land on a point occupied by exactly one opposing checker, or "blot." In this case, the blot has been "hit" and is placed in the middle of the board on the bar that divides the two sides of the playing surface. A checker may never land on a point occupied by two or more opposing checkers; thus, no point is ever occupied by checkers from both players simultaneously.[27][28] There is no limit to the number of checkers that can occupy a point or the bar at any given time.

Checkers placed on the bar must re-enter the game through the opponent's home board before any other move can be made. A roll of 1 allows the checker to enter on the 24-point (opponent's 1), a roll of 2 on the 23-point (opponent's 2), and so forth, up to a roll of 6 allowing entry on the 19-point (opponent's 6). Checkers may not enter on a point occupied by two or more opposing checkers. Checkers can enter on unoccupied points, or on points occupied by a single opposing checker; in the latter case, the single checker is hit and placed on the bar. A player may not move any other checkers until all checkers belonging to that player on the bar have re-entered the board.[28] If a player has checkers on the bar, but rolls a combination that does not allow any of those checkers to re-enter, the player does not move. If the opponent's home board is completely "closed," with all six points are each occupied by two or more checkers, there is no roll that will allow a player to enter a checker from the bar, and that player stops rolling and playing until at least one point becomes open (occupied by one or zero checkers) due to the opponent's moves.

A turn ends only when the player has removed his or her dice from the board. Prior to this moment, a move can be undone and replayed an unlimited number of times.

Bearing off

When all of a player's checkers are in that player's home board, that player may start removing them; this is called "bearing off." A roll of 1 may be used to bear off a checker from the 1-point, a 2 from the 2-point, and so on. If all of a player's checkers are on points lower than the number showing on a particular die, the player must use that die to bear off one checker from the highest occupied point.[28] For example, if a player rolls a 6 and a 5, but has no checkers on the 6-point and two on the 5-point, then the 6 and the 5 must be used to bear off the two checkers from the 5-point. When bearing off, a player may also move a lower die roll before the higher even if that means the full value of the higher die is not fully utilized. For example, if a player has exactly one checker remaining on the 6-point, and rolls a 6 and a 1, the player may move the 6-point checker one place to the 5-point with the lower die roll of 1, and then bear that checker off the 5-point using the die roll of 6; this is sometimes useful tactically. As before, if there is a way to use all moves showing on the dice by moving checkers within the home board or by bearing them off, the player must do so. If a player's checker is hit while in the process of bearing off, that player may not bear off any others until it has been re-entered into the game and moved into the player's home board, according to the normal movement rules.

The first player to bear off all fifteen of their own checkers wins the game. When keeping score in backgammon, the points awarded depend on the scale of the victory. A player who bears off all fifteen pieces when the opponent has borne off at least one, wins a single game worth 1 point. If all fifteen have been borne off before the opponent gets at least one checker off, this is a gammon or double game worth 2 points. A backgammon or triple game is worth 3 points and occurs when the losing player has borne off no pieces and has one or more on the bar and/or in the winner's home table (inner board).[28]

Doubling cube

To speed up match play and to provide an added dimension for strategy, a doubling cube is usually used. The doubling cube is not a die to be rolled, but rather a marker, with the numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 inscribed on its sides to denote the current stake. At the start of each game, the doubling cube is placed on the midpoint of the bar with the number 64 showing; the cube is then said to be "centered, on 1." When the cube is still centered, either player may start their turn by proposing that the game be played for twice the current stakes. Their opponent must either accept ("take") the doubled stakes or resign ("drop") the game immediately.

Whenever a player accepts doubled stakes, the cube is placed on their side of the board with the corresponding power of two facing upward, to indicate that the right to redouble, which is to offer to continue doubling the stakes, belongs exclusively to that player.>[28] If the opponent drops the doubled stakes, they lose the game at the current value of the doubling cube. For instance, if the cube showed the number 2 and a player wanted to redouble the stakes to put it at 4, the opponent choosing to drop the redouble would lose two, or twice the original stake.

There is no limit on the number of redoubles. Although 64 is the highest number depicted on the doubling cube, the stakes may rise to 128, 256, and so on. In money games, a player is often permitted to "beaver" when offered the cube, doubling the value of the game again, while retaining possession of the cube.[30]

A variant of the doubling cube "beaver" is the "raccoon." Players who doubled their opponent, seeing the opponent beaver the cube, may in turn then double the stakes once again ("raccoon") as part of that cube phase before any dice are rolled. The opponent retains the doubling cube. An example of a "raccoon" is the following: White doubles Black to 2 points, Black accepts then beavers the cube to 4 points; White, confident of a win, raccoons the cube to 8 points, while Black retains the cube. Such a move adds greatly to the risk of having to face the doubling cube coming back at 8 times its original value when first doubling the opponent (offered at 2 points, counter offered at 16 points) should the luck of the dice change.

Some players may opt to invoke the "Murphy rule" or the "automatic double rule." If both opponents roll the same opening number, the doubling cube is incremented on each occasion yet remains in the middle of the board, available to either player. The Murphy rule may be invoked with a maximum number of automatic doubles allowed and that limit is agreed to prior to a game or match commencing. When a player decides to double the opponent, the value is then a double of whatever face value is shown (for example, if two automatic doubles have occurred putting the cube up to 4, the first in-game double will be for 8 points). The Murphy rule is not an official rule in backgammon and is rarely, if ever, seen in use at officially sanctioned tournaments.

The "Jacoby rule," named after Oswald Jacoby, allows gammons and backgammons to count for their respective double and triple values only if the cube has already been offered and accepted. This encourages a player with a large lead to double, possibly ending the game, rather than to play it to conclusion hoping for a gammon or backgammon. The Jacoby rule is widely used in money play but is not used in match play.[31]

The "Crawford rule," named after John R. Crawford, is designed to make match play more equitable for the player in the lead. If a player is one point away from winning a match, that player's opponent will always want to double as early as possible in order to catch up. Whether the game is worth one point or two, the trailing player must win to continue the match. To balance the situation, the Crawford rule requires that when a player first reaches a score one point short of winning, neither player may use the doubling cube for the following game, called the "Crawford game." After the Crawford game, normal use of the doubling cube resumes. The Crawford rule is routinely used in tournament match play.[31] It is possible for a Crawford game to never occur in a match.

If the Crawford rule is in effect, then another option is the "Holland rule," named after Tim Holland, which stipulates that after the Crawford game, a player cannot double until after at least two rolls have been played by each side. It was common in tournament play in the 1980s, but is now rarely used.[32]

Strategy and tactics

Backgammon is played in two principal variations, money and match play:

- Money play means that every point counts evenly and every game stands alone, whether money is actually being wagered or not; sometimes it is called unlimited play.

- Match play means that the players play until one side scores (or exceeds) a certain number of points. The format has a significant effect on strategy. In a match, the objective is not to win the maximum possible number of points, but rather to simply reach the score needed to win the match, so optimal play may depend on the match score. In money play, the theoretically correct checker play and cube action would never vary based on the score.

Backgammon has an established opening theory, although it is less detailed than that of chess. The tree of positions expands rapidly because of the number of possible dice rolls and the moves available on each turn. Recent computer analysis has offered more insight on opening plays, but the midgame is reached quickly. After the opening, backgammon players frequently rely on some established general strategies, combining and switching among them to adapt to the changing conditions of a game.

There are several strategies or "game plans" to achieve a win:

- The running game is a strategy minimizing or breaking contact while ahead in the race.[33]

- The holding game is holding a point on the opponent's side of the board, called an anchor. As the game progresses, the player may gain an advantage by hitting an opponent's blot from the anchor or by rolling large doubles that allow the checkers to escape into a running game.[33]

- The priming game involves building a wall of checkers, called a prime, covering a number of consecutive points. This obstructs opposing checkers that are behind the prime. A checker trapped behind a six-point prime cannot escape until the prime is broken.[33]

- The attacking game, sometimes called a blitz, is a strategy of covering the home board as quickly as possible while hitting one's opponent and keeping them on the bar. Because the opponent has difficulty re-entering from the bar or escaping, a player can quickly gain a race advantage and win the game, often with a gammon.[27]

A backgame is a strategy that involves holding two or more anchors in an opponent's home board while being substantially behind in the race.[34] The anchors obstruct the opponent's checkers and create opportunities to hit them as they move home. The backgame is generally used only to salvage a game wherein a player is already significantly behind. Using a backgame as an initial strategy is usually unsuccessful.[27][33]

Duplication refers to the placement of checkers such that one's opponent needs the same dice rolls to achieve different goals. For example, players may position all of their blots in such a way that the opponent must roll a 2 in order to hit any of them, reducing the probability of being hit more than once.[27][33]

Diversification refers to a complementary tactic of placing one's own checkers in such a way that more numbers are useful.[33]

The pipcount is number of pips needed to move a player's checkers around and off the board. Many positions require a measurement of a player's standing in the race, for example, in making a doubling cube decision, or in determining whether to run home and begin bearing off. The difference between the two players' pip counts is a measure of the leader's racing advantage. For cube decisions, a number of formulas have been developed over the years,[35] including the Thorpe count,[36] the Ward count, the Keith count,[37] and iSight.[38] These calculations enable a player to determine whether to offer or take a double based on the pipcount in non-contact positions.

Cube handling

Two theoretical models provide a basis for cube handling, in other words, when to offer a double and when to accept an offered double. Both ignore the effects of gammons and backgammons.

- The dead cube model ignores the advantage the taker gets from having sole access to the cube. It estimates that the takepoint (the minimum game winning chances to accept a cube) is 25 percent and the doubling window opens at 50 percent.

- The live cube model assumes a maximum value for sole cube access (the taker may use the cube most efficiently by either raising the stakes or doubling out the opponent). It estimates that the takepoint is 20 percent and the doubling window opens at 80 percent.

In practice, the takepoints and doubling points are somewhere in between, since while cube ownership cannot be ignored, assuming maximal efficiency for a re-cube is also not a valid assumption.[39] Ignoring gammons and backgammons, the takepoint in money play is about 22 percent.[40] All of the above ignores gammons and backgammons for either side, so in practice the calculation of takepoints is more complicated.[41]

Equity

A player's equity in a money or unlimited game is the average expected value that will be won or lost as a result of that game. For instance, if a player is certain to win but has no chance of a gammon or backgammon their equity is 1 and their opponent's equity is −1. If it is certain that the player will win a backgammon, their equity is 3 and their opponent's equity is −3.

For example, in the illustration, the player's winning chances are 75 percent, which corresponds to an equity of +0.5.[42]

- Suppose there are only two checkers left on the board and the player on-roll has a checker on their six point and the opponent has a checker on their one point. The player on-roll will bear off with 27/36 rolls or 75 percent of the time. If the game was played from that position 100 times the on-roll player would win ~75 games and their opponent would win ~25 for a net win of ~50 points per 100 games. The on-roll player's equity would be .5 and their opponent's would be −.5.

- If the doubling cube was accessible they could offer the cube and increase their equity to 1: either their opponent passes the cube and the game is over, or their opponent takes the cube and loses 100 points per 100 games (instead of the 50 with the cube centered). This illustrates that the raw takepoint for money play is 25 percent.

Competitive play

Club and tournament play

Played ad hoc in cafés and bars, clubs throughout Europe host backgammon with informal gatherings to play throughout the day or in the evening as well as by way of social interaction. A few clubs offer specialized backgammon services, maintaining their own facilities or offering computer analysis of troublesome plays.

A backgammon chouette permits three or more players to participate in a single game, often for money. One player competes against a team of all the other participants, and positions rotate after each game. Chouette play often permits the use of multiple doubling cubes.[27]

Backgammon clubs may also organize tournaments. Large club tournaments sometimes draw competitors from other regions, with final matches viewed by hundreds of spectators. The top players at regional tournaments often compete in major national and international championships.

International competition

The first world championship competition in backgammon was held in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1967. Tim Holland was declared the winner that year and at the tournament the following year. For unknown reasons, there was no championship in 1970, but in 1971, Tim Holland again won the title. The competition remained in Las Vegas until 1975, when it moved to Paradise Island in the Bahamas. The years 1976, 1977 and 1978 saw "dual" World Championships, one in the Bahamas attended by the Americans, and the European Open Championships in Monte Carlo with mostly European players. In 1979, Lewis Deyong, who had promoted the Bahamas World Championship for the prior three years, suggested that the two events be combined.[43]

By the twenty-first century, the largest international tournaments had established the basis of a tour for top professional players. Major tournaments are held yearly worldwide. "Party Gammon" held the world's first ever million dollar backgammon tournament in the Bahamas in January 2007 with a prize pool of one million dollars.[44] In 2008, the World Series of Backgammon ran the world's largest international events in London, the UK Masters, the biggest tournament ever held in the UK with 128 international class players; the Nordic Open, which instantly became the largest in the world with around 500 players in all flights and 153 in the championship, and Cannes, which hosted the Riviera Cup, the traditional follow-up tournament to the World Championships. Cannes also hosted the WSOB championship, the WSOB finale, which saw 16 players play three-point shootout matches for €160,000.

The World Backgammon Association (WBA) has been holding the biggest backgammon tour on the circuit since 2007, the "European Backgammon Tour" (EBGT).[45]

Computer backgammon

Backgammon entered the computer era in the 1990s when software was developed to play and analyze games, and for people to play one another over the internet.

Backgammon has been studied considerably by computer scientists. Neural networks and other approaches have offered significant advances to software for gameplay and analysis. With 15 white and 15 black counters and 24 possible positions, backgammon has 18 quintillion possible legal positions.[46]

The first strong computer opponent was BKG 9.8. It was written by Hans Berliner in the late 1970s on a DEC PDP-10 as an experiment in evaluating board game positions. Early versions of BKG played badly even against poor players, but Berliner noticed that its critical mistakes were always at transitional phases in the game. He applied principles of fuzzy logic to improve its play between phases, and by July 1979, BKG 9.8 was strong enough to play against the reigning world champion Luigi Villa. It won the match 7–1, becoming the first computer program to defeat a world champion in any board game. Berliner stated that the victory was largely a matter of luck, as the computer received more favorable dice rolls.[47]

In the late 1980s, backgammon programmers found more success with an approach based on artificial neural networks. Neural network research has resulted in several proprietary programs. These programs not only play the game, but offer tools for analyzing games and detailed comparisons of individual moves. The strength of these programs lies in their neural networks' weights tables, which are the result of months of training. Without them, these programs play no better than a human novice.

- Johnson's Expert Backgammon, introduced in 1990, was the first commercially available software package to analyze positions and provide stats for wins, losses, gammons, and backgammons. It was based on conventional programming techniques and only achieved a level of play of weak intermediate.[48]

- TD-Gammon, written by Gerry Tesauro at IBM, used neural net techniques that allowed it to learn based on experience. A full package with rollouts was never released to the public.[48]

- JellyFish, written by Fredriik Dahl and released in 1994, was the first commercially available software based on neural networks, and like TD-Gammon its play approached or surpassed that of the best human players.[48]

- Snowie, written by André Nicoulin and Olivier Egger and released in 1998, was a neural-net program that had similar playing strength to its neural net predecessors, but had a more advanced user interface; in particular it could analyze an entire match instead of just one move at a time.[48]

- gnubg, written by many programmers as part of the gnu free software project, was released in 2001. It has a similar strength to JellyFish, but is free software. It is still supported and is available for Windows, MAC OS, and most varieties of Linux. Since it is open source, the source code is publicly available.[49]

- eXtreme Gammon, written by Xavier Dufaure de Citres and released in 2009, is available for Windows and mobile platforms. According to the Financial Times, the program is the best backgammon player in the world, and the near-exclusive study tool for all serious backgammon players.[50]

Real-time online play began with the First Internet Backgammon Server in July 1992,[51] but there are now a range of options.[52]

Another neural network software developed by Nikolaos Papachristou is Palamedes that was developed in the early 2000s. It can also play variations like Hypergammon, Portes, Plakoto, Fevga, Narde and has multiple engines for each one.

Related games

There are many relatives of backgammon within the tables family with different aims, modes of play, and strategies. Some are played primarily throughout one geographic region, and others add new tactical elements to the game. These other tables games commonly have a different starting position, restrict certain moves, or assign special value to certain dice rolls, but in some geographic games even the rules and direction of movement of the counters change, rendering them fundamentally different.

Acey-deucey is a relative of backgammon in which players start with no counters on the board, and must enter them onto the board at the beginning of the game. The roll of 1-2 is given special consideration, allowing the player, after moving the 1 and the 2, to select any desired doubles move. A player also receives an extra turn after a roll of 1-2 or of doubles.[22]

Nard is a traditional tables game from Persia which may be an ancestor of backgammon. It has a different opening layout in which all 15 pieces start on the 24th point. During play pieces may not be hit and there are no gammons or backgammons.

Ban-sugoroku is a Japanese game that is a close relative of backgammon. It utilizes the same starting position but has slightly different rules.

Gul bara, also called "Crazy Narde" or "Rosespring Backgammon," is an ancient genre of board games that includes Backgammon, Trictrac, and Nard. The game is popular in Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, Greece, Turkey, and North Macedonia. The play will iterate among Backgammon, Gul Bara, and Tapa until one of the players reaches a score of seven or five.

Coan ki is an ancient Chinese tables game.

Plakoto, Fevga, and Portes are three varieties of tables games played in Greece. Together, the three are referred to as Tavli and are usually played one after the other; game being three, five, or seven points.

Tavla, also called Takhteh or Takhte, is a Turkish variation.

Notes

- ↑ game-board The British Museum. Retrieved March 17, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Irving Finkel (ed.), Ancient Board Games in Perspective (British Museum Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0714111537).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 David Parlett, Oxford History of Board Games (Echo Point Books & Media, 2018, ISBN 978-1635617955).

- ↑ Tristan Donovan, It's All a Game: The history of board games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017, ISBN 978-1250082725).

- ↑ Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Dick Davis (trans.), Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings (Penguin Books, 2016, ISBN 978-0143108320).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Roland G. Austin, Zeno's Game of τάβλη The Journal of Hellenic Studies 54(2) (1934): 202–205. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ↑ Robert Charles Bell, Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (Dover Publications, 1979, ISBN 978-0486238555).

- ↑ Roland G. Austin, Roman Board Games. II Greece & Rome 4(11) (1935): 76–82. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 H.J.R. Murray, A History of Board-Games Other than Chess (Hassell Street Press, 2021 (original 1952), ISBN 978-1015003057)

- ↑ The Book of Games by Alfonso the Wise Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 David Cram, Jeffrey L. Forgeng, and Dorothy Johnson, Francis Willughby's Book of Games: A Seventeenth-Century Treatise on Sports, Games and Pastimes (Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-1859284605).

- ↑ Willard Fiske, Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature: With historical notes on other table-games (Alpha Edition, 2020 (original 1905), ISBN 978-9354045776).

- ↑ Henry B. Wheatley (ed.), The Diary of Samuel Pepys Vol. 9 (Aeterna, 2024 (original 1666), ISBN 1444470280).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Charles Cotton, The Compleat Gamester (Cornmarket Reprints, 1972 (original 1674), ISBN 978-0719114861.

- ↑ Edmond Hoyle, A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-gammon (Gale Ecco, 2018 (original 1753), ISBN 978-1379319771).

- ↑ Henry George Bohn, The Hand-Book of Games (Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1850), ISBN 978-0260208521).

- ↑ Bill Robertie, 501 Essential Backgammon Problems (Cardoza, 2004, ISBN 978-1580421386).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Michael Strato, Grand Duke Dmitri was Likely Inventor of Doubling in Backgammon Gammon Life, November 16, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ Joe Pasternack, The Father Of Modern Backgammon Gammon Village Magazine, September 20, 2001. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ Bernard Weinraub, Urge to Play Backgammon Sweeping Men's Clubs New York Times, January 13, 1966. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ Dale Kerr, World Championships of Backgammon Backgammon Galore!, September 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Oswald Jacoby and John Crawford, The Backgammon Book (The Viking Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0670144099).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Charles P. Wallace, Love of Backgammon: To Arabs, It's the 1 Game That Counts Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1988. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Marijean Boueri, Jill Boutros, and Joanne Sayad, Lebanon A to Z: A Middle Eastern Mosaic (Publishingworks, 2006, ISBN 0974480347).

- ↑ Chris Bray, Backgammon For Dummies (John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 978-0470770856).

- ↑ Tournament Rules: The board World Backgammon Federation (WBGF). Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Bill Robertie, Backgammon for Winners (Cardoza, 2002, ISBN 978-1580420433).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 Alfred H. Morehead, Geoffrey Mott-Smith, and Philip D. Morehead, Hoyle's Rules of Games (Plume, 2001, ISBN 978-0452283138).

- ↑ Rules of Backgammon Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ Bill Robertie, Early Beavers Gammon Village, August 1, 2001. Retrieved March 19, 2005.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Bill Robertie, Backgammon for Serious Players (Cardoza, 2022, ISBN 978-1580423953).

- ↑ Holland Rule Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 Paul Magriel and Renee Magriel Roberts, Backgammon (Clock & Rose Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1593860271).

- ↑ Back Game Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Pip Counting Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Simon Woodhead, Cube Handling in Races Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Tom Keith, Keith Count Cube Handling In Noncontact Positions. Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Axel Reichert, Improved Cube Handling in Races: Insights with Isight Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Rick Janowski, Take-Points in Money Games Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Phil Simborg, Backgammon Cube Strategy Made Simple Gammon Life, June 25, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Phil Simborg, When to Double Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Paul Lamford, Starting Out in Backgammon (Everyman Chess, 2001, ISBN 978-1857442823).

- ↑ Backgammon World Champs World Backgammon Association (WBA). Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ PartyGammon.com Million - World's First Million Dollar Backgammon Tournament! ReadyBetGo!, January 23, 2007. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ European Backgammon Tour Worldwide Backgammon Federation. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ↑ Sean Williams, Developing Positional Awareness The UK Backgammon Federation (UKBGF), January 3, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ↑ Hans J. Berliner, Backgammon Computer Program Beats World Champion Backgammon Galore!. Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 Jeremy Paul Bagai, Classic Backgammon Revisited (Foreworks, 2001, ISBN 978-0943292373).

- ↑ Albert Silver, All About GNU Backgammon Galore! Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ↑ Oliver Roeder, Backgammon's AI super-brain is for sale Financial Times, July 28, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ↑ Brief history of FIBS FIBS. Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ↑ Online Backgammon Sites The UK Backgammon Federation (UKBGF). Retrieved March 21, 2025.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bagai, Jeremy Paul. Classic Backgammon Revisited. Foreworks, 2001. ISBN 978-0943292373

- Bell, Robert Charles. Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Dover Publications, 1979. ISBN 978-0486238555

- Bohn, Henry George. The Hand-Book of Games. Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1850). ISBN 978-0260208521

- Boueri, Marijean, Jill Boutros, and Joanne Sayad. Lebanon A to Z: A Middle Eastern Mosaic. Publishingworks, 2006. ISBN 0974480347

- Bray, Chris. Backgammon For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. ISBN 978-0470770856

- Cotton, Charles. The Compleat Gamester. Cornmarket Reprints, 1972 (original 1674). ISBN 978-0719114861

- Cram, David, Jeffrey L. Forgeng, and Dorothy Johnson. Francis Willughby's Book of Games: A Seventeenth-Century Treatise on Sports, Games and Pastimes. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-1859284605

- Donovan, Tristan. It's All a Game: The history of board games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. Thomas Dunne Books, 2017. ISBN 978-1250082725

- Ferdowsi, Abolqasem, Dick Davis (trans.). Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings.(enguin Books, 2016. ISBN 978-0143108320

- Finkel, Irving. Ancient Board Games in Perspective. British Museum Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0714111537

- Fiske, Willard. Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature: With historical notes on other table-games. Alpha Edition, 2020 (original 1905). ISBN 978-9354045776

- Hoyle, Edmond. A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-gammon. Gale Ecco, 2018 (original 1753). ISBN 978-1379319771

- Jacoby, Oswald, and John Crawford. The Backgammon Book. The Viking Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0670144099

- Lamford, Paul. Starting Out in Backgammon. Everyman Chess, 2001. ISBN 978-1857442823

- Magriel, Paul, and Renee Magriel Roberts. Backgammon. Clock & Rose Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1593860271

- Morehead, Alfred H., Geoffrey Mott-Smith, and Philip D. Morehead. Hoyle's Rules of Games. Plume, 2001. ISBN 978-0452283138

- Murray, H.J.R. A History of Board-Games Other than Chess. Hassell Street Press, 2021 (original 1952). ISBN 978-1015003057

- Parlett, David. Oxford History of Board Games. Echo Point Books & Media, 2018. ISBN 978-1635617955

- Robertie, Bill. Backgammon for Winners. Cardoza, 2002. ISBN 978-1580420433

- Robertie, Bill. 501 Essential Backgammon Problems. Cardoza, 2004. ISBN 978-1580421386

- Robertie, Bill. Backgammon for Serious Players. Cardoza, 2022., ISBN 978-1580423953

- Wheatley Henry B. (ed.). The Diary of Samuel Pepys Vol. 9. Aeterna, 2024 (original 1666). ISBN 1444470280

External links

All links retrieved March 21, 2025.

- Backgammon Basics: How To Play US Backgammon Federation (USBGF)

- The Rules of Backgammon Masters of Traditional Games

- Top 10 historical board games The British Museum

- The History of Backgammon From The Backgammon Book by Oswald Jacoby and John R. Crawford, 1970.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.