Yggdrasill

- For other uses, see Yggdrasill (disambiguation).

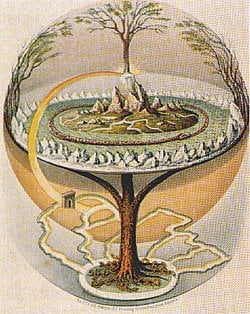

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil (Old Norse Yggdrasill, IPA: ˈygˌdrasilː; the extra -l is a nominative case marker) is the "World Tree", a gigantic ash tree, thought to connect all the nine worlds of Norse cosmology. Sometimes it is called Mímameiðr or Lérað. According mythology, Ásgard, Álfheim and Vanaheim rest on the branches of Yggdrasil. The trunk is the world-axis piercing through the center of Miðgarðr (often called Midgard), around which Jötunheim is situated, and below which lies Niðavellir, also called Svartálfheim. The three roots stretch down to Hel, Niflheim, and Muspelheim, although only the first world hosts a spring for Yggdrasil.

Yggdrasill in a Norse Context

As a central element of the Norse cosmology, Yggdrasill belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1]

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods (Asgard and Vanaheim, homes of the Aesir and Vanir, respectively), the realm of mortals (Midgard) and the frigid underworld (Niflheim), home of the frost giants. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots.

Etymology and alternative names

The most commonly accepted etymology of the name is ygg "terrible" + drasil "steed". Yggr is taken to be an epithet of Odin, giving a meaning of "Odin's steed", taken to refer to the nine nights Odin is said to have spent hanging from the tree in order to find the runes. The gallows are sometimes described in Old Norse poetry as the "horse of the hanged." Another interpretation of the name is "terrible horse", in which case the association with Odin may be secondary. A third interpretation, with etymological difficulties, is "yew-column", associating the tree with the Eihwaz rune ᛇ

Fjölsvinnsmál, a poem in the Poetic Edda, refers to the World Tree as Mimameid (ON: Mímameiðr, "Mímir's tree" ). Most probably, the tree is also identical to Lærad (ON: Læraðr) a tree whose leaves and twigs reach down to the roof of Valhalla and provide food for the goat Heiðrún and the stag Eikþyrnir that both live on the roof.

Characteristics

(Svipdagsmol 242) 30. "Mimameith [Mimir's Tree] its name, | and no man knows What root beneath it runs; And few can guess | what shall fell the tree, For fire nor iron shall fell it."

Mythic Accounts

Voluspa (describing the extent of her knowledge)

- Nine worlds I knew, | the nine in the tree

- With mighty roots | beneath the mold.[2]

Connection with the Norns (Voluspa (19), p. 8) An ash I know, | Yggdrasil its name, With water white | is the great tree wet; Thence come the dews | that fall in the dales, Green by Urth's well | does it ever grow.

(Grimnismol 96-99) 31. Three roots there are | that three ways run 'Neath the ash-tree Yggdrasil; 'Neath the first lives Hel, | 'neath the second the frost-giants, 'Neath the last are the lands of men.

32. Ratatosk is the squirrel | who there shall run On the ash-tree Yggdrasil; From above the words | of the eagle he bears, And tells them to Nithhogg beneath.

35. Yggdrasil's ash | great evil suffers, Far more than men do know; The hart bites its top, | its trunk is rotting, And Nithhogg gnaws beneath.

Three roots supported the trunk, with one passing through Niflheim, one through Jotunheim and one through Hel. Beneath the Asgard root lay the sacred Well of Urd (Urðabrunnr), and there dwelt the three Nornir, over whom even the gods had no power, and who, every day, watered the tree from the primeval fountain, so that its boughs remained green. Beneath the Jotunheim root lay the spring or well of Mímir (Mímisbrunnr); and beneath the Hel root the well Hvergelmir ("the Roaring Cauldron").

In the top of the tree was perched a giant rooster, or more often an eagle named Vidofnir, and sitting upon its forehead was a hawk named Vedrfolnir (Old Norse: Veðrfolnír). The Niflheim roots of Yggdrasil were gnawed at by a dragon, Níðhöggr. Ratatosk, a squirrel, scurried up and down the tree between Níðhöggr and the eagle, forwarding insults between them. There were also four stags feeding on the leaves of Yggdrasil: Duneyrr, Durathror, Dvalin, and Dainn.

The name Yggdrasil, interpreted as "Odin's steed," is taken to refer to Odin's self-sacrifice described in the Hávamál (although the tree is not explicitly identified as Yggdrasil):

- I hung on that windy tree for nine nights wounded by my own spear.

- I hung to that tree, and no one knows where it is rooted.

- None gave me food. None gave me drink. Into the abyss I stared

- until I spied the runes. I seized them up, and, howling, fell.

Ragnarök

Yggdrasil is also central in the myth of Ragnarök, the end of the world. The only two humans to survive Ragnarök (there are some survivors among the gods), Lif and Lifthrasir, are able to escape by sheltering in the branches of Yggdrasil, where they feed on the dew and are protected by the tree.

(VAFTHRUTHNISMOL 80-81) Othin spake: 44. "Much have I fared, | much have I found, Much have I got of the gods: What shall live of mankind | when at last there comes The mighty winter to men?"

Vafthruthnir spake: 45. "In Hoddmimir's wood | shall hide themselves Lif and Lifthrasir then; The morning dews | for meat shall they have, Such food shall men then find."

(Voluspa, p. 12 and ff.) 27. I know of the horn | of Heimdall, hidden Under the high-reaching | holy tree; (Heimdall's horn will be hidden (buried under Yggdrasil) until the end times)

(Voluspa, p. 20) 47. Yggdrasil shakes, | and shiver on high The ancient limbs, | and the giant is loose; To the head of Mim | does Othin give heed, But the kinsman of Surt | shall slay him soon.

Yggdrasill in Norse Religion

Germanic sacrifices

The Germanic custom of hanging sacrificial victims from trees was probably in reference to this myth (see also Human sacrifice, Tyr). In 1950, the preserved corpse of the so-called "Tollund Man" was found in a peat bog in Jutland. The excellent level of preservation made it possible to deduce that he had been ritually hanged and respectfully consigned to the bog, not more than a hundred yards from where a ritually hanged woman had been found some decades previously.

Germanic veneration of trees

Yggdrasil apparently had smaller counterparts as the Sacred tree at Uppsala, the enormous evergreen of unknown species that stood at the Temple at Uppsala and Irminsul, which was an oak venerated by the pagan Saxons and which was said to connect heaven and earth. The Old Norse form of Irmin was Jörmun and interestingly, just like Ygg, it was one of Odin's names. It appears, then, that Irminsul may have been representing a world tree corresponding to Yggdrasil among the pagan Saxons.

Germanic cultural fondness for tree symbolism appears to have been widespread, with other patron trees such as Thor's Oak appearing in surviving accounts (8th century) and Ahmad ibn Fadlan's account of his encounter with the Scandinavian Rus tribe in the early 10th century, describing them as tattooed from "fingernails to neck" with dark blue "tree patterns."

Potential origins

It has been proposed as an explanation for the World Tree myth that the Cirrus clouds – to a ground standing observer appearing to be virtually stationary on the sky – was imagined to be the branches of a gigantic tree, turned seemingly pale the same way that far away mountains do. Accordingly, rain was held to be the dew dropping from the World Tree. Two old German synonyms for clouds, Wetterbaum and Regenbaum (meaning Weather Tree and Rain Tree), are said to attest to this hypothesis.

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ Voluspa (2). Page 3.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Grammaticus, Saxo. The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

- "Völuspá" in The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.