Veliky Novgorod

| Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 604 |

| Region** | European Russia |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Novgorod, the third largest city in Russia, has deep historical roots to Russian culture as a whole.[1] Novgorod is famed as a center for Russian folk culture, because it does not experience the same influx of Western ideas and peoples found in Moscow or St. Petersburg. The preeminence of Veliky Novgorod in Russian culture is represented by the root of the name, where "Novgorod" is said to be the Russian word for "new city", and "Veliky" means "the Great".

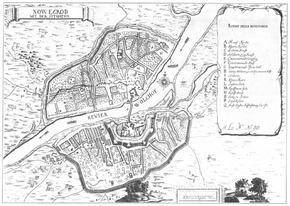

Geography

Ancient Novgorod rose to a political force partially due to its ideal location with easy access to both the Oka and the Volga rivers. It is located in the North-West region of Russia, an area commonly referred to as Russia's heartland. The title of the area reflects the high agricultural productivity of the region, as well as the overall economic importance of the area to Russia as a whole.

In modern times, when rivers are no longer the main means of conveyance, Novgorod can be reached by the Russian Route M10. It is situated between the major metropolises Moscow and St. Petersburg, and is rising to become a population center in its own right. Recent estimates put the population at 216, 856, which while lower than the measurements in Soviet Times, still represents a large city by Russian standards.

Economy

Education is an incredibly important part of the Novgorod culture, as it was one of the first cities in Russian history to build a schoolhouse large enough to hold three hundred students at once. The high levels of education in Novgorod directly spawned many of the key industries for the city, particularly the book making and printing industries. Novgorod also expressed its intellectual history through art, becoming a major center for icon painting and applied decorative arts.

Currently, much of the Novgorod economy is funded through foreign investment sources. Novgorod is widely considered to be one of the most economically open Russian cities, a fact corroborated by tax breaks offered to foreign investors by the local government. Foreign investors tend to focus on heavy industry, particularly the radio-electronic, furniture, chemical fields. The high levels of investment have had some effect on the local population, raising the living standard above many other urban centers in Russia. In particular, Novgorod has a smaller homeless population than Moscow or St. Petersburg.

History

Novgorod was among the first cities to be formed in ancient Russia. Due to its proximity to the rivers, a small civilization sprouted up that connected the Greek markets to the Russian and Baltic markets. Archaeological evidence regarding the trade dates the city back to the tenth century C.E. , when Christianity first made its way into Russia. [2] Along with the ideas of Christianity, religious evangelists brought trade items to be traded in urban centers to fund their travels. While some records mention Novgorod as an urban center prior to the tenth century C.E. it must be assumed that earlier accounts exaggerate the importance of the settlement, due to the lack of archaeological evidence to support a large city at an earlier time.

After the tenth century C.E., Novgorod emerged as a strong political and religious center. Its secure position was primarily due to Novogorod's strong military onslaught against Constantinople. As a result of the military campaign, Novgorod maintained equal trading rights with Byzantine and began a cultural interchange. East Slavic tribes from Byzantine began pouring into the ancient Slavic state, influencing the art and culture of Novgorod.

The growing economic and political authority of Novgorod soon drew the attention of Oleg of Novgorod, a political leader who led a campaign to capture Novgorod. Because of the power of Novgorod, it became the second most powerful city in the newly formed Kievan Rus. The city was ruled by a series of political organizations, called posadnicks, which governed when the ruler had no son to inherit the throne. When not being ruled by posadnicks, Novgorod had the good fortune to experience a series of benevolent rulers who governed with the best interest of the city's inhabitants in mind. The most notable among the benevolent leaders of Novgorod was Yaroslav I the Wise, who implemented the first written code of laws in the city.

Under a series of benevolent rulers, the inhabitants of Novgorod were steadily granted increased independence and political autonomy. As a result of their increased role in the political process, it soon became apparent to the inhabitants of Novgorod that a singular ruling authority was not necessary for Novgorod to function. As a result of this revelation, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince in 1136. In order to fill the political void, Novgorod established the Novgorod Republic, which invited and dismissed a series of princes in order to rule Novgorod. While the veche, or electing authority, maintained supreme nominal power, some powerful leaders were able to assert a strong agenda over the objections of the people.[3]

Novgorod, with its unique political structure,soon became a thriving center for arts and culture. During the Medieval Ages Novgorod gained its reputation for literacy and education, a reputation that stayed with the city for most of its legacy. Written records at this time are in the form of birch bark documents, many of which were written in the archbishop's scriptorium. Possibly due to the intellectual and cultural strength of Novgorod, Novgorod did not fall during the Mongol invasion of ancient Russia. During this invasion, many surrounding cities fell to the Mongol invaders, but the cultural beacon of Novgorod resisted the invasion.

Despite being able to resist the Mongol invaders, Novgorod began to falter politically in the early 15th century C.E. Many scholars trace Novgorod's crumbling political power to an inability to provide the basic needs for its inhabitants. The citizens of Novgorod were particularly threatened by a lack of grain, which drove many citizens close to starvation. In order to rectify the lack of bread Novgorod made a political agreement with Moscow and Tver to provide much needed grain. These cities used the agreement to exercise political control over Novgorod, and the city's independence began to weaken in proportionate to its dependence on Moscow and Tver for grain. Novgorod was eventually annexed by Moscow in 1478.

The difficulties for Novgorod continued in the Time of Trouble, when the city fell to Swedish troops. According to some accounts, the city voluntarily submitted to Swedish rule. Novgorod continued under Swedish authority for six years, after which time it was returned to Russia and allowed to rebuilt a level of political authority. After the transfer of Novgorod to Russia, Novgorod began an ambitious program of building and many of its most famous structures were constructed during this time period. Notable examples of this period of architecture include the Cathedral of the Sign and Vyazhischi Monastery. Novgorod became the administrative center of the Novgorod Governorate in 1727, demonstrating its reclaimed importance to Russia. Novgorod continued to be important to Russia until World War II, when German troops occupied the city and destroyed many of the historical and cultural landmarks.

Sights and Landmarks

The cultural and religious legacy of Novgorod is most apparent in the many churches that dot the countryside. The most apparent religious structure in the city is the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod, which was built between 1045 and 1050. [4] The Cathedral is one of the most finely preserved examples of 11th century Russian architecture. It is particularly noted for its Russian style architecture, sharply different from the French inspired architecture favored by previous Russian royal families. One of the most prominent features of the cathedral is its distinctive bronze gates, which were originally thought to have been made in Magdeburg during the 12th century C.E., but have now found to been purchased late into the 15th century. [5]

A distinctively different architectural style is apparent in the Saviour Cathedral of Kutyn Monastery, which is patterned after the cathedrals in Moscow. This church, along with other churches built during the fifteenth century, is patterned after Muscovite architectural trends.

Sister cities

Strasbourg, France

Strasbourg, France Rochester, New York, USA

Rochester, New York, USA Bielefeld, Germany

Bielefeld, Germany Watford, UK

Watford, UK Zibo, China

Zibo, China Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine Moss, Norway

Moss, Norway

Notes

- ↑ The Archaeology of Novgorod, by Valentin L. Yanin, in Ancient Cities, Special Issue, (Scientific American), pp 120–127, c 1994. Covers, History, Kremlin of Novgorod, Novgorod Museum of History, preservation dynamics of the soils, and the production of Birch bark documents.

- ↑ V. L. (Valentin Lavrent’evich) Ianin and M. Kh. (Mark Khaimovich) Aleshkovskii, “Proskhozhdenie Novgoroda: (k postanovke problemy),” Istoriia SSSR 2 (1971): 32-61.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, “The Iaroslavichi and the Novgorodian Veche 1230-1270: A Case Study on Princely Relations with the Veche,” Russian History/ Histoire Russe 31, No. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 2004): 39-59.

- ↑ Tatiana Tsarevskaia, St. Sophia's Cathedral in Novgorod (Moscow: Severnyi Palomnik, 2005), 3.

- ↑ Irena Daniec Jadwiga, The Message of Faith and Symbol in European Medieval Bronze Church Doors (Danbury, CT: Rutledge Books, 1999), Chapter III "An Enigma: The Medieval Bronze Church Door of Płock in the Cathedral of Novgorod," 67-97; Mikhail Tsapenko, ed., Early Russian Architecture (Moscow: Progress Publisher, 1969), 34-38

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Costantino, Maria. 2001. The Illustrated Flag Handbook. New York: Gramercy Books. ISBN 0-517-21810-0

- Lewis, Brenda Ralph. 2002. Great Civilizations. Bath: Paragon Publishing. ISBN 0-75256-141-3

- DK Publishing, Great Britain (Eyewitness Guide). New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 0756615429

External links

- Novgorod the Great site Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- Veliky Novgorod for tourists Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- The Faceted Palace of the Kremlin in Novgorod the Great site Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- Novgorod - monuments of ancient architectureRetrieved December 17, 2007.

- Guide to Novgorod Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- Introduction to Novgorod Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- What is Novgorod? Retrieved December 17, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.