Difference between revisions of "Sinan" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (70 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Copyedited}} | |

| − | + | [[Image:SehzadeMosqueExterior.jpg|thumb|300px|Etxerior of the Şehzade Mosque, begun in 1543]] | |

| − | His most famous work is the [[Suleiman Mosque]] in [[Istanbul]], although | + | '''Koca Mi‘mār Sinān Āġā''' ([[Ottoman Turkish language|Ottoman Turkish]]: خوجه معمار سنان آغا) <span dir="ltr">(April 15, 1489 - April 09, 1588)</span>, better known simply as '''Sinan''' was the chief [[architecture|architect]] and civil engineer for sultans [[Suleiman I]], [[Selim II]] and [[Murad III]]. During a period of 50 years, he was responsible for the construction or supervision of every major building in the [[Ottoman Empire]]. More than 300 structures are credited to him, exclusive of his more modest projects. |

| + | |||

| + | Born into a [[Christian]] family, he [[Religious conversion|converted]] to [[Islam]] after being drafted into government military service, where he traveled widely both as a commander of [[soldier]]s and a [[military]] [[engineer]]. By 1539, he had risen to the position of chief [[architect]] of [[Istanbul]] and the entire Ottoman Empire. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His most famous work is the [[Suleiman Mosque]] in [[Istanbul]], although he considered his masterpiece to be the [[Selimiye Mosque]] in nearby [[Edirne]]. He supervised an extensive governmental department and trained many assistants who also distinguished themselves, including [[Sedefhar Mehmet Ağa]], architect of the [[Sultan Ahmed Mosque]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Sinan is considered the greatest architect of the [[Ottoman architecture#Classical period|classical period]], and is often compared to [[Michelangelo]], his contemporary in the West. | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | Sinan | + | [[Image:Suleyman I of the Ottoman Empire.jpg|thumb|left|[[Suleiman I]] was sultan of the [[Ottoman Empire]] from 1520 until his death in 1566]] |

| + | [[Image:Khourrem.jpg|thumb|140px|Suleiman's wife Roxelana was one of Sinan's main patrons]] | ||

| + | Born a Christian in [[Anatolia]] in a small town called Ağırnas near the city of [[Kayseri]], Sinan's father's name is variously recorded as Abdülmenan, Abdullah, and Hristo (Hristos). In 1512, Sinan was conscripted into military service and went to [[Istanbul]] to join the [[Janissary]] corps, where he converted to [[Islam]]. He initially learned [[carpentry]] and [[mathematics]] and showed such talent that he soon became the assistant of leading architects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During this time, he was also trained as a [[cadet]], finally being admitted to the brotherhood of [[Janissaries]] after six years. After participating in several battles, he was promoted to captain of the Royal Guard and then given command of the Infantry Cadet Corps. He was later stationed in [[Austria]], where he commanded the 62nd Orta of the Rifle Corps. During this time, while using his knowledge of [[architecture]] to learn the weak points of enemy fortifications, he was also able to study European architecture and construction techniques. | ||

| − | + | In 1535 he participated in the [[Baghdad]] campaign as a commanding officer of the Royal Guard. During the campaign in the East, he assisted in the building of defenses and bridges, such as a bridge across the [[Danube]]. During the [[Persia]]n campaign he built ships to enable the army and the artillery to cross [[Lake Van]]. In 1537 he went on expedition to the Greek island of [[Corfu]], the Italian region of [[Apulia]], and finally to [[Moldavia]], giving him added exposure to the European architecture of the period. He also converted churches into [[mosque]]s. When the Ottoman army captured [[Cairo]], Sinan was promoted to chief architect of the city. | |

| − | + | In 1539, [[Çelebi Lütfi Pasha]], under whom Sinan had previously served, became [[Grand Vizier]] and appointed Sinan as chief architect of the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, where his duties included to supervise construction and the maintain the flow of supplies throughout the entire [[Ottoman Empire]]. He was also responsible for the design and construction of public works, such as [[road]]s, [[waterworks]] and [[bridge]]s. Over the coming years, Sinan transformed his office into that of Architect of the Empire, an elaborate government department with greater powers even than his supervising minister. He became the head of an entire corps of court architects, training a team of assistants, deputies, and pupils. | |

==Work== | ==Work== | ||

| − | His training as an army engineer gave Sinan an empirical approach to architecture rather than a theoretical one | + | His training as an army [[engineer]] gave Sinan an empirical approach to [[architecture]] rather than a theoretical one, making use of the knowledge garnered from his exposure to the great architectural achievements of [[Europe]] and the [[Middle East]], as well as his own innate talents. He eventually transformed established architectural practices in the [[Ottoman Empire]], amplifying and transforming the traditions by adding innovations and trying to approach the perfection of his art. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Early period=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Mimar Sinan - Mosquée Şehzade Mehmet, Istanbul (02).jpg|thumb|right|225px|Şehzade Mosque]] | |

| − | + | Sinan initially continued the traditional pattern of Ottoman architecture, gradually exploring new possibilities. His first attempt to build an important monument was the [[Hüsrev Pasha Mosque]] and its double [[Madrasah|medresse]] in [[Aleppo]], [[Syria]]. It was built in the winter of 1536-1537 between two army campaigns for his commander-in-chief. Its hasty construction is demonstrated in the coarseness of execution and crude decoration. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | His first major commission as the royal architect in Istanbul was the construction of a modest Haseki Hürrem complex for [[Roxelana]] (Hürem Sultan), the wife of Sultan [[Süleyman the Magnificent]]. Here, Sinan had to follow the plans drawn by his predecessors. He retained the traditional arrangement of the available space without any innovations. Nevertheless the structure was already better built and more elegant than the Aleppo mosque. | |

| − | |||

| − | His first major commission as the royal architect was the construction of a modest Haseki Hürrem complex for [[Roxelana]] (Hürem Sultan), the wife of | ||

| − | In 1541, he started the construction of the mausoleum | + | In 1541, he started the construction of the [[mausoleum]] ''(türbe)'' of the Grand Admiral [[Hayreddin Barbarossa]], which stands on the shore of [[Beşiktaş]] on the European side of Istanbul, at the site where the admiral's fleet used to assemble. Oddly enough, the admiral was not buried there, and the mausoleum has been severely neglected. |

| − | [[Mihrimah Sultana]], the only daughter of | + | [[Mihrimah Sultana]], the only daughter of Suleiman who became the wife of the Grand Vizier [[Rüstem Pasha]], gave Sinan the commission to build a mosque with a ''[[Madrassa|medrese]]'' (college), an ''[[imaret]]'' (soup kitchen), and a ''sibyan [[mekteb]]'' ([[Qur'an]] school) in [[Üsküdar]]. This [[Iskele Mosque]] (or Jetty Mosque) shows several hallmarks of Sinan's mature style: a spacious, high-vaulted basement, slender [[minaret]]s, and a single-domed [[canopy]] flanked by three semi-domes ending in three semicircular recesses, and a broad double [[portico]]. The construction was finished in 1548. |

| − | + | In 1543, when Suleiman's son and heir to the throne Ṣehzade Mehmet died at the age of 22, the sultan ordered Sinan to build a new major mosque with an adjoining complex in his memory. This [[Şehzade Mosque]], larger and more ambitious than his previous ones, is considered Sinan's first masterpiece. Sinan added four equal half-domes to the large central [[dome]], supporting this superstructure with four massive but elegant free-standing, octagonal fluted piers, and four additional piers incorporated in each lateral wall. In the corners, above roof level, four turrets serve as stabilizing anchors. This concept of this construction is markedly different from the plans of traditional Ottoman architecture. | |

| − | === | + | === Second stage === |

| − | + | [[Image:Bath of Roxelane Istanbul 2007.jpg|thumb|left|Bath house at the Haseki Hürrem complex built for Suleiman's wife [[Roxelana]]]] | |

| + | [[Image:Istanbul - Süleymaniye camii - Foto G. Dall'Orto 26-5-2006 - 15.jpg|thumb|250px|The [[Süleymaniye Mosque]]]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Suleymaniye domes.jpg|thumb|250px|Interior of the [[Süleymaniye Mosque]]]] | ||

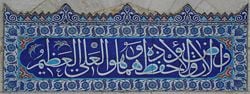

| + | [[Image:Süleymaniye Camii İstanbul IKalligraphie.jpg|thumb|250px|Ceramic Tiles featuring [[Calligraphy]] in the Süleymaniye Mosque]] | ||

| + | By 1550 [[Suleiman the Magnificent]] was at the height of his powers. He gave the order to Sinan to build a great mosque, the [[Süleymaniye]], surrounded by a complex consisting of four colleges, a soup kitchen, [[hospital]], asylum, [[bath]], [[caravanserai]], and a [[hospice]] for travelers. Sinan, now heading a department with a great number of assistants, finished this formidable task in seven years. Through this monumental achievement, Sinan emerged from the anonymity of his predecessors. In this work, Sinan is thought to have been influenced by the ideas of the [[Renaissance]] architect [[Leone Battista Alberti]] and other Western architects, who sought to construct the ideal church, reflecting the perfection of [[geometry]] in architecture. Sinan adapted his ideal to Islamic tradition, glorifying [[Allah]] by emphasizing simplicity more than elaboration. He tried to achieve the largest possible volume under a single central [[dome]], believing that this structure, based on the circle, is the perfect [[Geometry|geometrical]] figure, representing the [[perfection]] of [[God]]. | ||

| − | While he was | + | While he was occupied with the construction of the Süleymaniye, Sinan planned and supervised many other constructions. In 1550 he built a large [[inn]] in the Galata district of Istanbul. He completed mosque and a funeral monument for Grand Vizier [[Ibrahim Pasha]] at [[Silivrikapı]] (in Istanbul) in 1551. Between 1553 and 1555, he built a mosque at [[Beşiktaş]] for Grand Admiral Sinan Pasha which was a smaller version of the [[Üç Ṣerefeli Mosque]] at [[Edirne]], copying the old form while attempting innovative solutions to weaknesses in its construction. In 1554 Sinan used this form to create a mosque for the next [[grand vizier]], [[Kara Ahmed Pasha]], in Istanbul, his first [[hexagon]]al mosque. By using this form, he could reduce the side domes to half-domes and set them in the corners at an angle of 45 degrees. He used the same principle later in mosques such as the [[Sokollu Mehmed Pasha]] Mosque at [[Kadırga]] and the Atık Valide Mosque at [[Űskűdar]]. |

| − | Sinan built | + | In 1556 Sinan built the [[Haseki Hürrem Hamam]], replacing the ancient [[Baths of Zeuxippus]] still standing close to the [[Hagia Sophia]]. This would become one of the most beautiful ''hamams'' he ever constructed. In 1559 he built the Cafer Ağa academy below the forecourt of the Hagia Sophia. In the same year he began the construction of a small mosque for [[İskender Pasha]] at [[Kanlıka]], beside the [[Bosporus]], one of the many such minor commissions which his office received over the years. |

| − | + | [[Image:Istanbul - Mesquita de Mihrimah.JPG|thumb|250px|The [[Mihrimah Sulatana Mosque]]]] | |

| − | + | In 1561, Sinan began the construction of the [[Rüstem Pasha Mosque]], situated just below the [[Süleymaniye]]. This time the central form was octagonal, modeled on the monastery church of [[Saints Sergius and Bacchus]], with four small semi-domes set in the corners. In the same year, he built a funeral monument for [[Rüstem Pasha]] in the garden of the [[Şehzade Mosque]], decorated with the finest tiles from the city of [[Iznik]]. | |

| − | + | For Rüstem Pasha's widow, he built the [[Mihrimah Sulatana Mosque]] at Edirne Gate, on the highest of the seven hills of Istanbul. He constructed this mosque on a vaulted platform, accentuating its hilltop site.<ref>There is some speculation concerning the dates of this mosque. It is now generally accepted to be between 1562 and 1565.</ref> Wanting to achieve a sense of grandeur, he used one of his most imaginative designs, involving new support systems and lateral spaces to increase the area available for [[windows]]. It features a central dome 37 meters high and 20 meters wide on a square base with two lateral galleries, each with three [[cupola]]s. At each corner of the square stands a gigantic pier connected with immense arches, each with 15 large square windows and four circular ones, flooding the interior with light. This revolutionary building was as close to the style of [[Gothic architecture]] style as Ottoman structure would allow. | |

| − | + | Between 1560 and 1566 Sinan designed and at least partly supervised the building of a mosque in Istanbul for [[Zal Mahmut Pasha]] on a hillside beyond Ayvansaray. On the outside, the mosque rises high, with its east wall pierced by four tiers of windows. Inside, there are three broad galleries making the interior look compact. The heaviness of this structure makes the dome look unexpectedly lofty. | |

| − | + | === Final stage === | |

| + | [[Image:Edirne 7333 Nevit.JPG|thumb|400px|The [[Selimiye Mosque]], built by Sinan in 1575, is considered his masterpiece.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Selimiye Mosque, Dome.jpg|thumb|250px|Interior of the dome of the Selimiye Mosque]] | ||

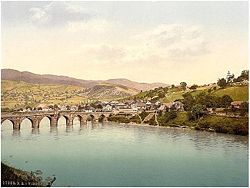

| + | [[Image:Mehmed Pasa Sokolovic Bridge Visegrad 1900.JPG|thumb|250px||The [[Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge]] across the [[Drina River]] in the east of [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]]]] | ||

| − | + | In this late stage of his life, Sinan sought to create magnificent buildings of unified form and sublimely elegant interiors. To achieve this, he eliminated all the unnecessary subsidiary spaces beyond the supporting piers of the central dome. This can be seen in the [[Sokollu Mehmet Paşa]] Mosque in Istanbul (1571-1572) and in the [[Selimiye Mosque]] in Edirne. In other buildings of his final period, Sinan experimented with spatial and mural treatments that were new in classical Ottoman architecture. | |

| − | + | Sin considered the [[Selimiye Mosque]] to be his masterpiece. Breaking free of the handicaps of traditional Ottoman architecture, this mosque marks the apex of classical Ottoman architecture. One of his motivations in this work was to create a dome even larger than that of the [[Hagia Sophia]]. Here, he finally realized his aim of creating the optimum, completely unified, domed interior, using an octagonal central dome 31.28 m wide and 42 m high, supported by eight elephantine piers of [[marble]] and [[granite]]. These supports lack any [[capital]]s, leading to the optical effect that the arches grow integrally out of the piers. He increased the three-dimensional effect by placing the lateral galleries far away. Windows flood the interior with light. Buttressing semi-domes are set in the four corners of the square under the dome. The weight and the internal tensions are thus hidden, producing an airy and elegant effect rarely seen under a central dome. Four [[minaret]]s—each 83 m high, the tallest in the Muslim world—are placed at the corners of the prayer hall, accentuating the vertical posture of this mosque that already dominates the city. Sinan was more than 80 years old when the building was finished. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Other notable projects in his later period include the [[Taqiyya al-Sulaimaniyya]] [[caravanserai|khan]] and mosque in [[Damascus]], still considered one of the city's most notable monuments, as well as the [[Banya Bashi Mosque]] in [[Sofia]], [[Bulgaria]], currently the only functioning mosque in the city. He also built [[Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge]] in [[Višegrad]] across the [[Drina River]] in the east of [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] which is now on the [[UNESCO World Heritage Site]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Sinan died in 1588 and is buried in a tomb of his own design, in the cemetery just outside the walls of the [[Suleiman Mosque|Süleymaniye Mosque]] to the north, across a street named Mimar Sinan Caddesi in his honor. He was buried near the tombs of his greatest patrons, [[Sultan Suleiman]] and his Ruthenian wife [[Haseki Hürrem]] known as [[Roxelana]] in the West. | |

| − | He | ||

| − | == | + | == Legacy== |

| − | + | [[Image:MimarSinan-Detail.jpg|thumb|Sinan is likely the figure shown at left at the tomb of Sultan Süleyman I]] | |

| + | Sinan's genius lies in the organization of space and the resolution of the tensions created by his revolutionary designs. He was an innovator in the use of decoration and motifs, merging them into the architectural forms as a whole. In his mosques, he accentuated the central space under the dome by flooding it with light from the many windows and incorporated the main building into complex, making the mosques more than simply monuments to God's glory but also serving the needs of the community as academies, community centers, hospitals, inns, and charitable institutions. | ||

| − | + | Several of his students distinguished themselves, especially [[Sedefhar Mehmet Ağa]], architect of the [[Sultan Ahmed Mosque]]. However, when Sinan died, the classical Ottoman architecture had reached its climax. Indeed, if he had one weakness, it is that his students retreated to earlier models. | |

| − | + | In modern times his name is was given to a [[Sinan (crater)|a crater on the planet Mercury]] and a Turkish state university, the [[Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts]] in Istanbul. During his tenure of 50 years of the post of imperial architect, Sinan is said to have designed, constructed, or supervised 476 buildings, 196 of which still survive. This include: | |

| − | During his tenure | + | |

| − | + | *94 large mosques ''(camii),'' | |

| − | *94 large mosques | ||

*57 colleges, | *57 colleges, | ||

| − | *52 smaller mosques | + | *52 smaller mosques ''(mescit),'' |

| − | *48 bath-houses | + | *48 bath-houses ''([[hamam]]),'' |

| − | *35 palaces | + | *35 palaces ''(saray),'' |

| − | *22 mausoleums | + | *22 mausoleums ''(türbe),'' |

*20 [[caravanserai]] (''kervansaray''; ''han''), | *20 [[caravanserai]] (''kervansaray''; ''han''), | ||

| − | *17 public kitchens | + | *17 public kitchens ''(imaret),'' |

*8 bridges, | *8 bridges, | ||

*8 store houses or granaries | *8 store houses or granaries | ||

| − | *7 Koranic schools | + | *7 Koranic schools ''([[Madrassa|medrese]]),'' |

*6 [[aqueduct]]s, | *6 [[aqueduct]]s, | ||

| − | *3 hospitals | + | *3 hospitals ''(darüşşifa)'' |

Some of his works: | Some of his works: | ||

| − | |||

* [[Azapkapi Sokullu]] Mosque in [[Istanbul]] | * [[Azapkapi Sokullu]] Mosque in [[Istanbul]] | ||

* [[Caferağa Medresseh]] | * [[Caferağa Medresseh]] | ||

| Line 102: | Line 113: | ||

* [[Yavuz Sultan Selim Madras]] | * [[Yavuz Sultan Selim Madras]] | ||

* [[Mimar Sinan Bridge]] in [[Büyükçekmece]] | * [[Mimar Sinan Bridge]] in [[Büyükçekmece]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Freely, John, and Augusto Romano Burelli. ''Sinan: Architect of Süleyman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Golden Age.'' London: Thames and Hudson, 1992. ISBN 9780500341209 | |

| − | * | + | * Goodwin, Godfrey. ''Sinan: Ottoman Architecture and Its Values Today.'' London: Saqi books, 1993. ISBN 9780863561726 |

| − | + | * Necipoğlu, Gülru, Arben N. Arapi, and Reha Gunay. ''The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780691123264 | |

| − | + | * Rogers, J. M. ''Sinan: Makers of Islamic civilization.'' London: I.B. Tauris in association with the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, 2006. ISBN 9781845110963 | |

| − | + | * Sinan, and Howard Crane; with Esra Akin, Gulru Necipoglu, eds. ''Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-Century Texts.'' Leiden: Brill, 2006. ISBN 9789004141681 | |

| − | * | ||

| − | * Gülru | ||

| − | * J.M. | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 29, 2023. | |

| − | * [http://www.pbase.com/dosseman/edirne_turkey | + | |

| − | + | * [http://www.pbase.com/dosseman/edirne_turkey The city of Edirne, with many pictures of the Selimiye Mosque] | |

| − | + | * [http://mimoza.marmara.edu.tr/~avni/H62SANAT/mimarsinan.hayati.htm 'Master Builder of the 16th Century Ottoman Mosque'] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | * [http://mimoza.marmara.edu.tr/~avni/H62SANAT/mimarsinan.hayati.htm Master Builder of the 16th Century Ottoman Mosque] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|259653937}} | {{credit|259653937}} | ||

| Line 145: | Line 135: | ||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| + | [[category:art]] | ||

| + | [[category:Engineers and Inventors]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history of the Middle East]] | ||

| + | [[category:Architecture]] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:27, 29 January 2023

Koca Mi‘mār Sinān Āġā (Ottoman Turkish: خوجه معمار سنان آغا) (April 15, 1489 - April 09, 1588), better known simply as Sinan was the chief architect and civil engineer for sultans Suleiman I, Selim II and Murad III. During a period of 50 years, he was responsible for the construction or supervision of every major building in the Ottoman Empire. More than 300 structures are credited to him, exclusive of his more modest projects.

Born into a Christian family, he converted to Islam after being drafted into government military service, where he traveled widely both as a commander of soldiers and a military engineer. By 1539, he had risen to the position of chief architect of Istanbul and the entire Ottoman Empire.

His most famous work is the Suleiman Mosque in Istanbul, although he considered his masterpiece to be the Selimiye Mosque in nearby Edirne. He supervised an extensive governmental department and trained many assistants who also distinguished themselves, including Sedefhar Mehmet Ağa, architect of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque.

Sinan is considered the greatest architect of the classical period, and is often compared to Michelangelo, his contemporary in the West.

Background

Born a Christian in Anatolia in a small town called Ağırnas near the city of Kayseri, Sinan's father's name is variously recorded as Abdülmenan, Abdullah, and Hristo (Hristos). In 1512, Sinan was conscripted into military service and went to Istanbul to join the Janissary corps, where he converted to Islam. He initially learned carpentry and mathematics and showed such talent that he soon became the assistant of leading architects.

During this time, he was also trained as a cadet, finally being admitted to the brotherhood of Janissaries after six years. After participating in several battles, he was promoted to captain of the Royal Guard and then given command of the Infantry Cadet Corps. He was later stationed in Austria, where he commanded the 62nd Orta of the Rifle Corps. During this time, while using his knowledge of architecture to learn the weak points of enemy fortifications, he was also able to study European architecture and construction techniques.

In 1535 he participated in the Baghdad campaign as a commanding officer of the Royal Guard. During the campaign in the East, he assisted in the building of defenses and bridges, such as a bridge across the Danube. During the Persian campaign he built ships to enable the army and the artillery to cross Lake Van. In 1537 he went on expedition to the Greek island of Corfu, the Italian region of Apulia, and finally to Moldavia, giving him added exposure to the European architecture of the period. He also converted churches into mosques. When the Ottoman army captured Cairo, Sinan was promoted to chief architect of the city.

In 1539, Çelebi Lütfi Pasha, under whom Sinan had previously served, became Grand Vizier and appointed Sinan as chief architect of the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, where his duties included to supervise construction and the maintain the flow of supplies throughout the entire Ottoman Empire. He was also responsible for the design and construction of public works, such as roads, waterworks and bridges. Over the coming years, Sinan transformed his office into that of Architect of the Empire, an elaborate government department with greater powers even than his supervising minister. He became the head of an entire corps of court architects, training a team of assistants, deputies, and pupils.

Work

His training as an army engineer gave Sinan an empirical approach to architecture rather than a theoretical one, making use of the knowledge garnered from his exposure to the great architectural achievements of Europe and the Middle East, as well as his own innate talents. He eventually transformed established architectural practices in the Ottoman Empire, amplifying and transforming the traditions by adding innovations and trying to approach the perfection of his art.

Early period

Sinan initially continued the traditional pattern of Ottoman architecture, gradually exploring new possibilities. His first attempt to build an important monument was the Hüsrev Pasha Mosque and its double medresse in Aleppo, Syria. It was built in the winter of 1536-1537 between two army campaigns for his commander-in-chief. Its hasty construction is demonstrated in the coarseness of execution and crude decoration.

His first major commission as the royal architect in Istanbul was the construction of a modest Haseki Hürrem complex for Roxelana (Hürem Sultan), the wife of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Here, Sinan had to follow the plans drawn by his predecessors. He retained the traditional arrangement of the available space without any innovations. Nevertheless the structure was already better built and more elegant than the Aleppo mosque.

In 1541, he started the construction of the mausoleum (türbe) of the Grand Admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa, which stands on the shore of Beşiktaş on the European side of Istanbul, at the site where the admiral's fleet used to assemble. Oddly enough, the admiral was not buried there, and the mausoleum has been severely neglected.

Mihrimah Sultana, the only daughter of Suleiman who became the wife of the Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, gave Sinan the commission to build a mosque with a medrese (college), an imaret (soup kitchen), and a sibyan mekteb (Qur'an school) in Üsküdar. This Iskele Mosque (or Jetty Mosque) shows several hallmarks of Sinan's mature style: a spacious, high-vaulted basement, slender minarets, and a single-domed canopy flanked by three semi-domes ending in three semicircular recesses, and a broad double portico. The construction was finished in 1548.

In 1543, when Suleiman's son and heir to the throne Ṣehzade Mehmet died at the age of 22, the sultan ordered Sinan to build a new major mosque with an adjoining complex in his memory. This Şehzade Mosque, larger and more ambitious than his previous ones, is considered Sinan's first masterpiece. Sinan added four equal half-domes to the large central dome, supporting this superstructure with four massive but elegant free-standing, octagonal fluted piers, and four additional piers incorporated in each lateral wall. In the corners, above roof level, four turrets serve as stabilizing anchors. This concept of this construction is markedly different from the plans of traditional Ottoman architecture.

Second stage

By 1550 Suleiman the Magnificent was at the height of his powers. He gave the order to Sinan to build a great mosque, the Süleymaniye, surrounded by a complex consisting of four colleges, a soup kitchen, hospital, asylum, bath, caravanserai, and a hospice for travelers. Sinan, now heading a department with a great number of assistants, finished this formidable task in seven years. Through this monumental achievement, Sinan emerged from the anonymity of his predecessors. In this work, Sinan is thought to have been influenced by the ideas of the Renaissance architect Leone Battista Alberti and other Western architects, who sought to construct the ideal church, reflecting the perfection of geometry in architecture. Sinan adapted his ideal to Islamic tradition, glorifying Allah by emphasizing simplicity more than elaboration. He tried to achieve the largest possible volume under a single central dome, believing that this structure, based on the circle, is the perfect geometrical figure, representing the perfection of God.

While he was occupied with the construction of the Süleymaniye, Sinan planned and supervised many other constructions. In 1550 he built a large inn in the Galata district of Istanbul. He completed mosque and a funeral monument for Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha at Silivrikapı (in Istanbul) in 1551. Between 1553 and 1555, he built a mosque at Beşiktaş for Grand Admiral Sinan Pasha which was a smaller version of the Üç Ṣerefeli Mosque at Edirne, copying the old form while attempting innovative solutions to weaknesses in its construction. In 1554 Sinan used this form to create a mosque for the next grand vizier, Kara Ahmed Pasha, in Istanbul, his first hexagonal mosque. By using this form, he could reduce the side domes to half-domes and set them in the corners at an angle of 45 degrees. He used the same principle later in mosques such as the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque at Kadırga and the Atık Valide Mosque at Űskűdar.

In 1556 Sinan built the Haseki Hürrem Hamam, replacing the ancient Baths of Zeuxippus still standing close to the Hagia Sophia. This would become one of the most beautiful hamams he ever constructed. In 1559 he built the Cafer Ağa academy below the forecourt of the Hagia Sophia. In the same year he began the construction of a small mosque for İskender Pasha at Kanlıka, beside the Bosporus, one of the many such minor commissions which his office received over the years.

In 1561, Sinan began the construction of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, situated just below the Süleymaniye. This time the central form was octagonal, modeled on the monastery church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, with four small semi-domes set in the corners. In the same year, he built a funeral monument for Rüstem Pasha in the garden of the Şehzade Mosque, decorated with the finest tiles from the city of Iznik.

For Rüstem Pasha's widow, he built the Mihrimah Sulatana Mosque at Edirne Gate, on the highest of the seven hills of Istanbul. He constructed this mosque on a vaulted platform, accentuating its hilltop site.[1] Wanting to achieve a sense of grandeur, he used one of his most imaginative designs, involving new support systems and lateral spaces to increase the area available for windows. It features a central dome 37 meters high and 20 meters wide on a square base with two lateral galleries, each with three cupolas. At each corner of the square stands a gigantic pier connected with immense arches, each with 15 large square windows and four circular ones, flooding the interior with light. This revolutionary building was as close to the style of Gothic architecture style as Ottoman structure would allow.

Between 1560 and 1566 Sinan designed and at least partly supervised the building of a mosque in Istanbul for Zal Mahmut Pasha on a hillside beyond Ayvansaray. On the outside, the mosque rises high, with its east wall pierced by four tiers of windows. Inside, there are three broad galleries making the interior look compact. The heaviness of this structure makes the dome look unexpectedly lofty.

Final stage

In this late stage of his life, Sinan sought to create magnificent buildings of unified form and sublimely elegant interiors. To achieve this, he eliminated all the unnecessary subsidiary spaces beyond the supporting piers of the central dome. This can be seen in the Sokollu Mehmet Paşa Mosque in Istanbul (1571-1572) and in the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne. In other buildings of his final period, Sinan experimented with spatial and mural treatments that were new in classical Ottoman architecture.

Sin considered the Selimiye Mosque to be his masterpiece. Breaking free of the handicaps of traditional Ottoman architecture, this mosque marks the apex of classical Ottoman architecture. One of his motivations in this work was to create a dome even larger than that of the Hagia Sophia. Here, he finally realized his aim of creating the optimum, completely unified, domed interior, using an octagonal central dome 31.28 m wide and 42 m high, supported by eight elephantine piers of marble and granite. These supports lack any capitals, leading to the optical effect that the arches grow integrally out of the piers. He increased the three-dimensional effect by placing the lateral galleries far away. Windows flood the interior with light. Buttressing semi-domes are set in the four corners of the square under the dome. The weight and the internal tensions are thus hidden, producing an airy and elegant effect rarely seen under a central dome. Four minarets—each 83 m high, the tallest in the Muslim world—are placed at the corners of the prayer hall, accentuating the vertical posture of this mosque that already dominates the city. Sinan was more than 80 years old when the building was finished.

Other notable projects in his later period include the Taqiyya al-Sulaimaniyya khan and mosque in Damascus, still considered one of the city's most notable monuments, as well as the Banya Bashi Mosque in Sofia, Bulgaria, currently the only functioning mosque in the city. He also built Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad across the Drina River in the east of Bosnia and Herzegovina which is now on the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sinan died in 1588 and is buried in a tomb of his own design, in the cemetery just outside the walls of the Süleymaniye Mosque to the north, across a street named Mimar Sinan Caddesi in his honor. He was buried near the tombs of his greatest patrons, Sultan Suleiman and his Ruthenian wife Haseki Hürrem known as Roxelana in the West.

Legacy

Sinan's genius lies in the organization of space and the resolution of the tensions created by his revolutionary designs. He was an innovator in the use of decoration and motifs, merging them into the architectural forms as a whole. In his mosques, he accentuated the central space under the dome by flooding it with light from the many windows and incorporated the main building into complex, making the mosques more than simply monuments to God's glory but also serving the needs of the community as academies, community centers, hospitals, inns, and charitable institutions.

Several of his students distinguished themselves, especially Sedefhar Mehmet Ağa, architect of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque. However, when Sinan died, the classical Ottoman architecture had reached its climax. Indeed, if he had one weakness, it is that his students retreated to earlier models.

In modern times his name is was given to a a crater on the planet Mercury and a Turkish state university, the Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts in Istanbul. During his tenure of 50 years of the post of imperial architect, Sinan is said to have designed, constructed, or supervised 476 buildings, 196 of which still survive. This include:

- 94 large mosques (camii),

- 57 colleges,

- 52 smaller mosques (mescit),

- 48 bath-houses (hamam),

- 35 palaces (saray),

- 22 mausoleums (türbe),

- 20 caravanserai (kervansaray; han),

- 17 public kitchens (imaret),

- 8 bridges,

- 8 store houses or granaries

- 7 Koranic schools (medrese),

- 6 aqueducts,

- 3 hospitals (darüşşifa)

Some of his works:

- Azapkapi Sokullu Mosque in Istanbul

- Caferağa Medresseh

- Selimiye Mosque in Edirne

- Süleymaniye Complex

- Kilic Ali Pasha Complex

- Molla Celebi Complex

- Haseki Baths

- Piyale Pasha Mosque

- Sehzade Mosque

- Mihrimah Sultan Complex in Edirnekapi

- Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad

- Nisanci Mehmed Pasha Mosque

- Rüstem Pasha Mosque

- Zal Mahmud pasha Mosque

- Kadirga Sokullu Mosque

- Koursoum Mosque or Osman Shah Mosque in Trikala

- Al-Takiya Al-Suleimaniya in Damascus

- Yavuz Sultan Selim Madras

- Mimar Sinan Bridge in Büyükçekmece

Notes

- ↑ There is some speculation concerning the dates of this mosque. It is now generally accepted to be between 1562 and 1565.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Freely, John, and Augusto Romano Burelli. Sinan: Architect of Süleyman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Golden Age. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992. ISBN 9780500341209

- Goodwin, Godfrey. Sinan: Ottoman Architecture and Its Values Today. London: Saqi books, 1993. ISBN 9780863561726

- Necipoğlu, Gülru, Arben N. Arapi, and Reha Gunay. The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780691123264

- Rogers, J. M. Sinan: Makers of Islamic civilization. London: I.B. Tauris in association with the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, 2006. ISBN 9781845110963

- Sinan, and Howard Crane; with Esra Akin, Gulru Necipoglu, eds. Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-Century Texts. Leiden: Brill, 2006. ISBN 9789004141681

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- The city of Edirne, with many pictures of the Selimiye Mosque

- 'Master Builder of the 16th Century Ottoman Mosque'

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.