Difference between revisions of "Romantic love" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | + | [[Image:Francesco Hayez 053.jpg|thumb|200px|Romeo and Juliet]] | |

| − | "'''Romantic love'''" | + | "'''Romantic love'''" refers to the connection between "[[love]]" and the general idea of "romance," according to more traditional usages of the terms. Historically the term "romance" did not necessarily imply love relationships, but rather was seen as an artistic expression of one's innermost desires; sometimes ''including'' love, sometimes not. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The romantic love of [[knights]] and [[damsels]], called [[courtly love]], emerged in the early [[medieval]] ages (eleventh century [[France]]), derived from [[Plato|Platonic]], [[Aristotelian]] love, and the writings of the [[Roman]] poet, [[Ovid]] (and his ''ars amatoria''). Such romantic love was often portrayed as not to be [[consummated]], but as transcendentally motivated by a deep respect for the lady and earnestly pursued in chivalric deeds rather than through sexual relations.<ref>[http://www.iep.utm.edu/l/love.htm The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love] ''www.iep.utm.edu'' Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Today, romance is still sometimes viewed as an expressionistic or artful form, but within the context of "romantic" relationships it usually implies an active expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person intimately with no promise for lasting commitment or marriage. It is often an exaggerated or decorated expression of love.<ref> [http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=68503&dict=CALD Romance] ''dictionary.cambridge.org'', Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> "Romance" in this sense can therefore be defined as attachment, fascination, or enthusiasm for someone of the opposite sex. | ||

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| + | The English word "romance" developed from a vernacular dialect within the [[French]] language, meaning "verse narrative," referring to the style of speech and writing, and artistic talents within [[elite]] classes. The word derives from the Latin "Romanicus," meaning "of the Roman style," of "from Rome." European medieval vernacular tales were usually about chivalric adventure, not combining with the theme of love until late into the seventeenth century. The word "romance" also has developed with various meanings in other languages, such as the early nineteenth century Spanish and Italian definitions of "adventure" and "passion," sometimes combining the idea of a "love affair" or "idealistic quality." | ||

| − | + | The more current and Western traditional terminology meaning a particularly ardent type of love, often transcending moral limits, is believed to have originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily in the French culture. This idea is what has spurred the connection between the words "romantic" and "lover," thusly creating the English phrase "romantic love" (i.e "loving like the Romans do"). However, the precise origins of such a connection are unknown. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As a literary style, the romantic genre has existed since before 1812. Here, the term "romantic" means "characteristic of an ideal love affair." [[Romanticism]], the artistic and intellectual movement that originated in late eighteenth-century Western Europe. In music, the romantic movement was characterized by the free expression of imagination and emotion, displays of instrumental virtuosity, and experimentation with orchestral form. | |

| − | + | ==History and definition== | |

| + | ''[[Courtly love]]'', a term first popularized by [[Gaston Paris]] in 1883 and closely related to the concept of romantic love, was a medieval European notion of the ennobling love which found its genesis in the ducal and princely courts of present-day southern [[France]] at the end of the eleventh century, and which had a civilizing effect on [[knight]]ly behavior. In essence, the concept of courtly love sought to reconcile erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent".<ref>Francis X. Newman, ed. 1968. The Meaning of Courtly Love, vii.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Courtly love saw high born women as an ennobling spiritual and moral force, a view that was in opposition to ecclesiastical sexual attitudes. Rather than being critical the mutual desire between men and women as sinful, the [[poet]]s and [[bard]]s praised it as the highest good. The Church, on the other hand, saw the purpose of marriage (finally declared a sacrament of the Church at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215) as procreation—with any sexual relations beyond that purpose seen as contrary to [[Christian]] values. Thus, romantic love, at the root of courtly love, resembles the modern concept of ''true love'', in which such piety has become much less of an issue, at least in post-[[Reformation]] [[Christianity]]. | |

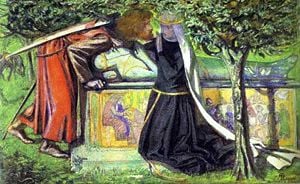

| − | + | [[Image:Dante Gabriel Rossetti- Arthur's Tomb - The Last Meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere.JPG|thumb|300px|The Last Meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere at Arthur's tomb.]] | |

| − | + | ''Romantic love'' distinguishes moments and situations within [[interpersonal relationship]]s. Initially, the concept emphasized [[emotions]] (especially those of [[affection]], [[intimacy]], [[compassion]], [[appreciation]], and general "liking") rather than sexual pleasure. But, romantic love, in the [[abstract]] sense of the term, is traditionally referred to as involving a mix of emotional and sexual desire for another [[person]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Modern romantic love is akin to [[Aristotle]]'s description of the love two people find in the harmony of each other's virtues—"one soul and two bodies," as he poetically put it. Such love is deemed to be of a high status, ethically, aesthetically, and even metaphysically, compared to mere sexual intimacy. Within an existing relationship romantic love can be defined as a temporary freeing or optimizing of [[intimacy]], either in a particularly luxurious manner (or the opposite as in the "natural"), or perhaps in greater spirituality, irony, or peril to the relationship. | |

| − | + | Romantic love is often contrasted to marriages of political or economic conveniences, especially arranged marriages in which a woman feels trapped in a relationship with an unattractive or abusive husband. The cultural traditions of [[marriage]] and [[betrothal]] are often in [[conflict]] with the spontaneity and absolute quality of romance. However it is possible that romance and love can exist between the partners within those customs. | |

| − | + | The ''tragic'' contradictions between romance and society are forcibly portrayed in such examples as the Arthurian story of [[Lancelot]] and [[Guinevere]], Tolstoy's ''[[Anna Karenina]]'', Flaubert's ''[[Madame Bovary]]'', and [[Shakespeare]]'s ''Romeo and Juliet.'' The protagonists in these stories were driven to tragedy by forces seemingly outside of their control, within the context of a romantic love which cannot be fulfilled. Alternatively, these lovers may be seen as going beyond the bounds of the original ideal of romantic love—in which the lovers were meant to express only a spiritual but not sexual love unless they could be married—but fulfilling the modern concept of romantic love which transcends moral boundaries and seeks fulfillment even at the risk of one's life. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Pessimistic views== | ==Pessimistic views== | ||

| + | Romantic love is sometimes directly compared with [[Platonic love]] alone, which precludes sexual relations. In certain modern usages it also takes on a fully [[asexual]] sense, rather than the classical sense in which sexual drives are (often) sublimated for the sake of or instead of marriage. [[Unrequited love]] can be romantic, but it too, occurs due to the [[sublimation]] or withholding of reciprocal affection, emotion or sex with no concept or possibility of commitment or marriage. | ||

| − | + | [[Schopenhauer]] saw romantic love as no more than a device of nature for reproducing the species. "Once our work is done," he wrote, "the love we had for our mate leaves us and there is nothing we can do about it."<ref>Schopenhauer, 1973, p. 241.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Kierkegaard]], a great proponent of marriage and romantic love who never himself married, went a bit further. In a speech about marriage given in his monumental treatise, ''Either/Or'', one of the pseudonymous authors attempts to show that because marriage is fundamentally lacking in passion, the nature of marriage, unlike romance, is in fact and [[ironically]] explainable by a man who has experience of neither marriage nor love. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 59: | Line 41: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *[[Alberoni, Francesco]] | + | * [[Alberoni, Francesco]]. ''Falling in Love.'' Random House Inc (T); 1st American ed edition, 1983. ISBN 978-0394530079 |

| − | *Kierkegaard, Søren. | + | * Kierkegaard, Søren. ''Stages on Life's Way: Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 11''. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition, 1988. ISBN 978-0691020495 |

| − | *Levi-Strauss, Claude. ''Structural Anthropolgy.'' Basic Books; New Ed edition | + | * Levi-Strauss, Claude. ''Structural Anthropolgy.'' Basic Books; New Ed edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0465095162 |

| − | *Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics). | + | * McWilliams, Peter. ''Love 101: To Love Oneself Is the Beginning of a Lifelong Romance''. Prelude Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931580727 |

| − | *Rougemont, Denis de. | + | * Nietzsche, Friedrich. ''Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics)''. Dover Publications; Dover Ed edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0486445663 |

| − | *Schopenhauer, Arthur. '' Essays and Aphorisms''. Penguin Classics | + | * Rougemont, Denis de. ''Love in the Western World.'' Schocken, 1990. ISBN 978-0805209501 |

| + | * Schopenhauer, Arthur. '' Essays and Aphorisms''. Penguin Classics, 1973. ISBN 978-0140442274 | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | *[http://www. | + | All links retrieved December 15, 2022. |

| + | |||

| + | *[http://www.livescience.com/health/050531_love_sex.html Love More Powerful than Sex, Study Claims] by Robert Roy Britt, LiveScience Senior Writer (posted: May 31, 2005) ''www.livescience.com'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/l/love.htm The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love] ''www.iep.utm.edu'' | ||

| + | |||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|153789001}} | {{Credit|153789001}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:58, 16 December 2022

"Romantic love" refers to the connection between "love" and the general idea of "romance," according to more traditional usages of the terms. Historically the term "romance" did not necessarily imply love relationships, but rather was seen as an artistic expression of one's innermost desires; sometimes including love, sometimes not.

The romantic love of knights and damsels, called courtly love, emerged in the early medieval ages (eleventh century France), derived from Platonic, Aristotelian love, and the writings of the Roman poet, Ovid (and his ars amatoria). Such romantic love was often portrayed as not to be consummated, but as transcendentally motivated by a deep respect for the lady and earnestly pursued in chivalric deeds rather than through sexual relations.[1]

Today, romance is still sometimes viewed as an expressionistic or artful form, but within the context of "romantic" relationships it usually implies an active expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person intimately with no promise for lasting commitment or marriage. It is often an exaggerated or decorated expression of love.[2] "Romance" in this sense can therefore be defined as attachment, fascination, or enthusiasm for someone of the opposite sex.

Etymology

The English word "romance" developed from a vernacular dialect within the French language, meaning "verse narrative," referring to the style of speech and writing, and artistic talents within elite classes. The word derives from the Latin "Romanicus," meaning "of the Roman style," of "from Rome." European medieval vernacular tales were usually about chivalric adventure, not combining with the theme of love until late into the seventeenth century. The word "romance" also has developed with various meanings in other languages, such as the early nineteenth century Spanish and Italian definitions of "adventure" and "passion," sometimes combining the idea of a "love affair" or "idealistic quality."

The more current and Western traditional terminology meaning a particularly ardent type of love, often transcending moral limits, is believed to have originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily in the French culture. This idea is what has spurred the connection between the words "romantic" and "lover," thusly creating the English phrase "romantic love" (i.e "loving like the Romans do"). However, the precise origins of such a connection are unknown.

As a literary style, the romantic genre has existed since before 1812. Here, the term "romantic" means "characteristic of an ideal love affair." Romanticism, the artistic and intellectual movement that originated in late eighteenth-century Western Europe. In music, the romantic movement was characterized by the free expression of imagination and emotion, displays of instrumental virtuosity, and experimentation with orchestral form.

History and definition

Courtly love, a term first popularized by Gaston Paris in 1883 and closely related to the concept of romantic love, was a medieval European notion of the ennobling love which found its genesis in the ducal and princely courts of present-day southern France at the end of the eleventh century, and which had a civilizing effect on knightly behavior. In essence, the concept of courtly love sought to reconcile erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent".[3]

Courtly love saw high born women as an ennobling spiritual and moral force, a view that was in opposition to ecclesiastical sexual attitudes. Rather than being critical the mutual desire between men and women as sinful, the poets and bards praised it as the highest good. The Church, on the other hand, saw the purpose of marriage (finally declared a sacrament of the Church at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215) as procreation—with any sexual relations beyond that purpose seen as contrary to Christian values. Thus, romantic love, at the root of courtly love, resembles the modern concept of true love, in which such piety has become much less of an issue, at least in post-Reformation Christianity.

Romantic love distinguishes moments and situations within interpersonal relationships. Initially, the concept emphasized emotions (especially those of affection, intimacy, compassion, appreciation, and general "liking") rather than sexual pleasure. But, romantic love, in the abstract sense of the term, is traditionally referred to as involving a mix of emotional and sexual desire for another person.

Modern romantic love is akin to Aristotle's description of the love two people find in the harmony of each other's virtues—"one soul and two bodies," as he poetically put it. Such love is deemed to be of a high status, ethically, aesthetically, and even metaphysically, compared to mere sexual intimacy. Within an existing relationship romantic love can be defined as a temporary freeing or optimizing of intimacy, either in a particularly luxurious manner (or the opposite as in the "natural"), or perhaps in greater spirituality, irony, or peril to the relationship.

Romantic love is often contrasted to marriages of political or economic conveniences, especially arranged marriages in which a woman feels trapped in a relationship with an unattractive or abusive husband. The cultural traditions of marriage and betrothal are often in conflict with the spontaneity and absolute quality of romance. However it is possible that romance and love can exist between the partners within those customs.

The tragic contradictions between romance and society are forcibly portrayed in such examples as the Arthurian story of Lancelot and Guinevere, Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Flaubert's Madame Bovary, and Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. The protagonists in these stories were driven to tragedy by forces seemingly outside of their control, within the context of a romantic love which cannot be fulfilled. Alternatively, these lovers may be seen as going beyond the bounds of the original ideal of romantic love—in which the lovers were meant to express only a spiritual but not sexual love unless they could be married—but fulfilling the modern concept of romantic love which transcends moral boundaries and seeks fulfillment even at the risk of one's life.

Pessimistic views

Romantic love is sometimes directly compared with Platonic love alone, which precludes sexual relations. In certain modern usages it also takes on a fully asexual sense, rather than the classical sense in which sexual drives are (often) sublimated for the sake of or instead of marriage. Unrequited love can be romantic, but it too, occurs due to the sublimation or withholding of reciprocal affection, emotion or sex with no concept or possibility of commitment or marriage.

Schopenhauer saw romantic love as no more than a device of nature for reproducing the species. "Once our work is done," he wrote, "the love we had for our mate leaves us and there is nothing we can do about it."[4]

Kierkegaard, a great proponent of marriage and romantic love who never himself married, went a bit further. In a speech about marriage given in his monumental treatise, Either/Or, one of the pseudonymous authors attempts to show that because marriage is fundamentally lacking in passion, the nature of marriage, unlike romance, is in fact and ironically explainable by a man who has experience of neither marriage nor love.

Notes

- ↑ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love www.iep.utm.edu Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Romance dictionary.cambridge.org, Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Francis X. Newman, ed. 1968. The Meaning of Courtly Love, vii.

- ↑ Schopenhauer, 1973, p. 241.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alberoni, Francesco. Falling in Love. Random House Inc (T); 1st American ed edition, 1983. ISBN 978-0394530079

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Stages on Life's Way: Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 11. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition, 1988. ISBN 978-0691020495

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropolgy. Basic Books; New Ed edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0465095162

- McWilliams, Peter. Love 101: To Love Oneself Is the Beginning of a Lifelong Romance. Prelude Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931580727

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics). Dover Publications; Dover Ed edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0486445663

- Rougemont, Denis de. Love in the Western World. Schocken, 1990. ISBN 978-0805209501

- Schopenhauer, Arthur. Essays and Aphorisms. Penguin Classics, 1973. ISBN 978-0140442274

External Links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Love More Powerful than Sex, Study Claims by Robert Roy Britt, LiveScience Senior Writer (posted: May 31, 2005) www.livescience.com

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love www.iep.utm.edu

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.