|

|

| (25 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{Started}}{{Contracted}} | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}} |

| | | | |

| − | {{Love table}}

| + | [[Image:Francesco Hayez 053.jpg|thumb|200px|Romeo and Juliet]] |

| − | "'''Romantic love'''" is a general term referring to the connection between "[[love]]" and the general idea of "romance," according to more traditional usages of the terms. Historically the term "romance" did not necessarily imply love relationships, but rather was seen as an artistic expression of one's innermost desires; sometimes ''including'' love, sometimes not. Romance is still sometimes viewed as an expressionistic, or artful form, but within the context of "romantic love" relationships it usually implies an expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person. It is (often) an exaggerated or decorated (more exciting than they really are) expression of love<ref> [http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=68503&dict=CALD Romance], Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, [http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/romance], dictionary.com</ref><ref>Love 101 : To Love Oneself Is the Beginning of a Lifelong Romance (The Life 101 Series) | + | "'''Romantic love'''" refers to the connection between "[[love]]" and the general idea of "romance," according to more traditional usages of the terms. Historically the term "romance" did not necessarily imply love relationships, but rather was seen as an artistic expression of one's innermost desires; sometimes ''including'' love, sometimes not. |

| − | by Peter McWilliams</ref>. "Romance" in this sense can therefore be defined as attachment, fascination, or enthusiasm for something or someone. Romantic love usually includes the characteristics of not being easily controlled, while not being overtly (initially at least) predicated on a desire for the physical act of sex.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==History and Etymology==

| + | The romantic love of [[knights]] and [[damsels]], called [[courtly love]], emerged in the early [[medieval]] ages (eleventh century [[France]]), derived from [[Plato|Platonic]], [[Aristotelian]] love, and the writings of the [[Roman]] poet, [[Ovid]] (and his ''ars amatoria''). Such romantic love was often portrayed as not to be [[consummated]], but as transcendentally motivated by a deep respect for the lady and earnestly pursued in chivalric deeds rather than through sexual relations.<ref>[http://www.iep.utm.edu/l/love.htm The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love] ''www.iep.utm.edu'' Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> |

| − | Historians believe that the actual English word "romance" developed from a vernacular dialect within the French language, meaning "verse narritve," referring to the style of speech and writing, and artistic talents within [[elite]] classes. The word was orginally an adverb of sorts, which was of the Latin origin "Romanicus," meaning "of the Roman style," "like the Romans" (see [[Roman]].) The connecting notion is that European medieval vernacular tales were usually about chivalric adventure, not combining the idea of love until late into the seventeenth century. The word "romance," or the equivilent thereof also has developed with other meanings in other languages, such as the early nineteenth century Spanish and Italian definitions of "adventurous" and "passionate," sometimes combining the idea of "love affair" or "idealistic quality."

| + | {{toc}} |

| | + | Today, romance is still sometimes viewed as an expressionistic or artful form, but within the context of "romantic" relationships it usually implies an active expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person intimately with no promise for lasting commitment or marriage. It is often an exaggerated or decorated expression of love.<ref> [http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=68503&dict=CALD Romance] ''dictionary.cambridge.org'', Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> "Romance" in this sense can therefore be defined as attachment, fascination, or enthusiasm for someone of the opposite sex. |

| | | | |

| − | The more current and Western traditional terminology meaning "court as lover" or the general idea of "romantic love" is believed to have originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily from that of the French culture. This idea is what has spurred the connection between the words "romantic" and "lover," thusly coining the English phrase "romantic love" (i.e "loving like the Roman's do".) But the precise origins of such a connection are unknown. | + | ==Etymology== |

| | + | The English word "romance" developed from a vernacular dialect within the [[French]] language, meaning "verse narrative," referring to the style of speech and writing, and artistic talents within [[elite]] classes. The word derives from the Latin "Romanicus," meaning "of the Roman style," of "from Rome." European medieval vernacular tales were usually about chivalric adventure, not combining with the theme of love until late into the seventeenth century. The word "romance" also has developed with various meanings in other languages, such as the early nineteenth century Spanish and Italian definitions of "adventure" and "passion," sometimes combining the idea of a "love affair" or "idealistic quality." |

| | | | |

| − | As a literary style, opposed to classical, the romantic style has existed since before 1812. Meaning "characteristic of an ideal love affair" (such as usually formed the subject of literary romances) is from 1666. The noun meaning "an adherent of romantic virtues in literature" is from 1827. Romanticism first recorded 1803 as "a romantic idea;" generalized sense of "a tendency toward romantic ideas" is first recorded in 1840.<ref> [http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=romantic&searchmode=none Online Etymology Dictionary]</ref>

| + | The more current and Western traditional terminology meaning a particularly ardent type of love, often transcending moral limits, is believed to have originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily in the French culture. This idea is what has spurred the connection between the words "romantic" and "lover," thusly creating the English phrase "romantic love" (i.e "loving like the Romans do"). However, the precise origins of such a connection are unknown. |

| | | | |

| − | == General definition of romantic love ==

| + | As a literary style, the romantic genre has existed since before 1812. Here, the term "romantic" means "characteristic of an ideal love affair." [[Romanticism]], the artistic and intellectual movement that originated in late eighteenth-century Western Europe. In music, the romantic movement was characterized by the free expression of imagination and emotion, displays of instrumental virtuosity, and experimentation with orchestral form. |

| − | === Within a relationship ===

| |

| − | '''Romantic love''' is a [[Relativism|relative]] term, that distinguishes moments and situations within [[interpersonal relationship]]s. There is often, initially, more emphasis on the [[emotions]] (especially those of [[love]], [[intimacy]],

| |

| − | [[compassion]], [[appreciation]], and general "liking") rather than physical pleasure. But, romantic love, in the [[abstract]] sense of the term, is traditionally referred to as involving a mix of emotional and sexual desire for another as a [[person]].

| |

| | | | |

| − | === In conflict with convention === | + | ==History and definition== |

| − | If one thinks of romantic love not as simply erotic freedom and expression, but as a breaking of that expression from a prescribed custom, romantic love is modern. There may have been a tension in primitive societies between marriage and the erotic, but this was mostly expressed in taboos regarding the menstrual cycle and birth. <ref>Power and Sexual Fear in Primitive Societies Margrit Eichler Journal of Marriage and the Family, Vol. 37, No. 4, Special Section: Macrosociology of the Family (Nov., 1975), pp. 917-926)</ref>

| + | ''[[Courtly love]]'', a term first popularized by [[Gaston Paris]] in 1883 and closely related to the concept of romantic love, was a medieval European notion of the ennobling love which found its genesis in the ducal and princely courts of present-day southern [[France]] at the end of the eleventh century, and which had a civilizing effect on [[knight]]ly behavior. In essence, the concept of courtly love sought to reconcile erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent".<ref>Francis X. Newman, ed. 1968. The Meaning of Courtly Love, vii.</ref> |

| − |

| |

| − | Before the 18th century, as now, there were many marriages that were not arranged, and arose out of more or less spontaneous relationships. But also after the 18th century, illicit relationships took on a more independent role. Subsequent [[sexual revolution]] has lessened the conflicts arising out of liberalism, but not eliminated them.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Anthropologists such as [[Claude Levi-Strauss]] show that there were complex forms of courtship in ancient as well as contemporary primitive societies. But there may not be evidence that members of such societies formed love relationships distinct from their established customs in a way that would parallel modern romance.<ref>Levi-Strauss pioneered the scientific study of the betrothal of cross cousins in such societies, as a way of solving such technical problems as the [[avunculate]] and the [[incest taboo]] (''Introducing Levi-Strauss'', p. 22-35.</ref>

| + | Courtly love saw high born women as an ennobling spiritual and moral force, a view that was in opposition to ecclesiastical sexual attitudes. Rather than being critical the mutual desire between men and women as sinful, the [[poet]]s and [[bard]]s praised it as the highest good. The Church, on the other hand, saw the purpose of marriage (finally declared a sacrament of the Church at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215) as procreation—with any sexual relations beyond that purpose seen as contrary to [[Christian]] values. Thus, romantic love, at the root of courtly love, resembles the modern concept of ''true love'', in which such piety has become much less of an issue, at least in post-[[Reformation]] [[Christianity]]. |

| | | | |

| − | Romantic love is then a relative term within any sexual relationship, but not relative when considered in contrast with custom. Within an existing relationship romantic love can be defined as a temporary freeing or optimizing of [[intimacy]], either in a particularly luxurious manner (or the opposite as in the "natural"), or perhaps in greater spirituality, irony, or peril to the relationship.

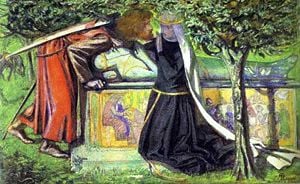

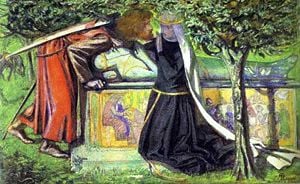

| + | [[Image:Dante Gabriel Rossetti- Arthur's Tomb - The Last Meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere.JPG|thumb|300px|The Last Meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere at Arthur's tomb.]] |

| | | | |

| − | The cultural traditions of [[Marriage]] and [[betrothal]] are the most basic customs in [[conflict]] with romance, however it is possible that romance and love can exist between the partners within those customs. [[Shakespeare]] and [[Kierkegaard]] describe similar viewpoints, to the effect that marriage and romance are not harmoniously ''in tune'' with each other. In ''[[Measure for Measure]]'', for example, "...there has not been, nor is there at this point, any display of affection between Isabella and the Duke, if by affection we mean something concerned with sexual attraction. The two at the end of the play love each other as they love virtue."<ref>The Marriage of Duke Vincentio and Isabella

| + | ''Romantic love'' distinguishes moments and situations within [[interpersonal relationship]]s. Initially, the concept emphasized [[emotions]] (especially those of [[affection]], [[intimacy]], [[compassion]], [[appreciation]], and general "liking") rather than sexual pleasure. But, romantic love, in the [[abstract]] sense of the term, is traditionally referred to as involving a mix of emotional and sexual desire for another [[person]]. |

| − | Norman Nathan Shakespeare Quarterly > Vol. 7, No. 1 (Winter, 1956), pp. 43-45</ref> Isabella, like all women, needs love, and she may reject marriage with the Duke because he seeks to beget an heir with her for her virtues, and she is not happy with the limited kind of love that implies. Shakespeare is arguing that marriage because of its purity can not simply incorporate romance.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Romance can also be tragic in its conflict with society. [[Tolstoy]] also focuses on the romantic limitations of marriage, and Anna Karenina prefers death to being married to her fiancée. Furthermore, in the speech about marriage that is given in Kierkegaard's ''[[Either/Or]]'', Kierkegaard attempts to show that it is because marriage is lacking in passion fundamentally, that the nature of marriage, unlike romance, is explainable by a man who has experience of neither marriage nor love.

| + | Modern romantic love is akin to [[Aristotle]]'s description of the love two people find in the harmony of each other's virtues—"one soul and two bodies," as he poetically put it. Such love is deemed to be of a high status, ethically, aesthetically, and even metaphysically, compared to mere sexual intimacy. Within an existing relationship romantic love can be defined as a temporary freeing or optimizing of [[intimacy]], either in a particularly luxurious manner (or the opposite as in the "natural"), or perhaps in greater spirituality, irony, or peril to the relationship. |

| | | | |

| − | In the following excerpt, from Shakespeare's [[Romeo and Juliet]], Romeo, in saying "all combined, save what thou must combine By holy marriage" implies that it is not marriage with Juliet that he seeks but simply to be joined with her romantically. That "I pray That thou consent to marry us" implies that the marriage means the removal of the social obstacle between the two opposing families, not that marriage is sought by Romeo with Juliet for any other particular reason, as adding to their love or giving it any more meaning.

| + | Romantic love is often contrasted to marriages of political or economic conveniences, especially arranged marriages in which a woman feels trapped in a relationship with an unattractive or abusive husband. The cultural traditions of [[marriage]] and [[betrothal]] are often in [[conflict]] with the spontaneity and absolute quality of romance. However it is possible that romance and love can exist between the partners within those customs. |

| | | | |

| − | <blockquote>

| + | The ''tragic'' contradictions between romance and society are forcibly portrayed in such examples as the Arthurian story of [[Lancelot]] and [[Guinevere]], Tolstoy's ''[[Anna Karenina]]'', Flaubert's ''[[Madame Bovary]]'', and [[Shakespeare]]'s ''Romeo and Juliet.'' The protagonists in these stories were driven to tragedy by forces seemingly outside of their control, within the context of a romantic love which cannot be fulfilled. Alternatively, these lovers may be seen as going beyond the bounds of the original ideal of romantic love—in which the lovers were meant to express only a spiritual but not sexual love unless they could be married—but fulfilling the modern concept of romantic love which transcends moral boundaries and seeks fulfillment even at the risk of one's life. |

| − | "Then plainly know my heart's dear love is set

| |

| − | On the fair daughter of rich Capulet:

| |

| − | As mine on hers, so hers is set on mine;

| |

| − | And all combined, save what thou must combine

| |

| − | By holy marriage: when and where and how

| |

| − | We met, we woo'd and made exchange of vow,

| |

| − | I'll tell thee as we pass; but this I pray,

| |

| − | That thou consent to marry us to-day."

| |

| − | —Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene II—by William Shakespear</blockquote>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Romantic love, however, may also be classified according to two categories, "popular romance" and "divine"(or "spiritual") romance. '''Popular romance''' may include but is not limited to the following types: idealistic, normal intense (such as the emotional aspect of "[[falling in love]]"), predictable as well as unpredictable, consuming (meaning consuming of time, energy and emotional withdrawals and bids), intense but out of control (such as the aspect of "falling out of love") material and commercial (such as societal gain mentioned in a later section of this article), physical and sexual, and finally grand and demonstrative. '''Divine (or spiritual) romance''' may include, but is not limited to these following types: realistic, as well as plausible unrealistic, optimistic as well as pessemistic (depending upon the particular beliefs held by each person within the relationship.), abiding (e.g. the theory that each person had a predetermined stance as an agent of choice; such as "choosing a husband" or "choosing a soulmate."), non-abiding (e.g. the theory that we do not choose our actions, and therefore our romantic love involvement has been drawn from sources outside of ourselves), predictable as well as unpredictable, self control (such as obedience and sacrifice within the context of the relationship) or lack therof (such as disobedience within the context of the relationship), emotional and personal, soulful (in the theory that the mind, soul, and body, are one connected entity), intimate, and infinite (such as the idea that love itself or the love of a god or God's "unconditional" love is or could be everlasting, if particular beliefs were, in fact, true.) <ref> Romance In Marriage: Perspectives, Pitfalls, and Principles, by Jason S. Carroll http://ce.byu.edu/cw/cwfamily/archives/2003/Carroll.Jason.pdf </ref> | + | ==Pessimistic views== |

| | + | Romantic love is sometimes directly compared with [[Platonic love]] alone, which precludes sexual relations. In certain modern usages it also takes on a fully [[asexual]] sense, rather than the classical sense in which sexual drives are (often) sublimated for the sake of or instead of marriage. [[Unrequited love]] can be romantic, but it too, occurs due to the [[sublimation]] or withholding of reciprocal affection, emotion or sex with no concept or possibility of commitment or marriage. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Gender differences and romance==

| + | [[Schopenhauer]] saw romantic love as no more than a device of nature for reproducing the species. "Once our work is done," he wrote, "the love we had for our mate leaves us and there is nothing we can do about it."<ref>Schopenhauer, 1973, p. 241.</ref> |

| − | [[John Gray (U.S._author)|John Gray]] is noted primarily for his claims that [[gender differences]] are the primary causes for many of the conflicts, problems, or issues between people of opposite sex in romantic relationships. However, in most of his material he neglects to mention instances that are similar between parties of same sex not involved romantically. John Gray does not seem to argue for differences in training, education, personal beliefs systems, personal experiences and attributive personality traits as being a collective unit of causes toward disruptions, disputes, and conflicts in any type of relationship, rather he focuses his theories primarily on the more traditional approach of gender based [[stereotypes]]. One factor, however, that is an observable trait dealing with gender differences is that of physical appearance. In fact, in terms of physical appearance, the concerns about [[attractiveness]] vary so widely between the sexes that it is difficult to examine the specific terms and variables common to both genders. But if we were to observe human behaviour only, there are certain trait characteristics that can be viewed as identical and/or similar between opposite sexes, whether involved romantically or not. The geniality and humanness characteristic of a society, however, appear to always cross gender boundaries at some level. In ''[[Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus]]'' Gray argued for reciprocity, by focusing on gender differences. In this way he popularized the view that men and women have special emotional needs belonging to their sex, and that an understanding of these might contribute to the conditions for relationships, and so also to romance.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==The psychology of romantic love==

| + | [[Kierkegaard]], a great proponent of marriage and romantic love who never himself married, went a bit further. In a speech about marriage given in his monumental treatise, ''Either/Or'', one of the pseudonymous authors attempts to show that because marriage is fundamentally lacking in passion, the nature of marriage, unlike romance, is in fact and [[ironically]] explainable by a man who has experience of neither marriage nor love. |

| − | Greek philosophers and authors had many theories of love, some of which are presented in Plato's ''Symposium'' where six Athenian friends including Socrates drink wine and each give a speech praising the god [[Eros]]. When his turn comes, [[Aristophanes]] says in his [[myth]]ical speech that sexual partners seek each other because they are descended from beings with spherical torsos, two sets of human limbs, genitalia on each side, and two faces back to back. Their three forms included the three permutations of pairs of gender (i.e. one masculine and masculine, another feminine and feminine, and the third masculine and feminine) and they were split by the gods to thwart the creatures' assault on heaven, recapitulated, according to the comic playwright, in other myths such as the [[Aloadae]].<ref>''Symposium 189d ff.</ref> This story is relevant to modern romance partly because of the image of reciprocity it shows between the sexes. In the final speech before [[Alcibiades]] arrives, [[Socrates]] gives his encomium of love and desire as a lack of being, namely, the being or form of [[beauty]]. [[Deleuze]] linked this idea of love as a lack mainly to [[Freud]], and Deleuze often criticized it.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Attraction, often based simply on common interests, can also appear mysterious and irrational, but [[psychotherapy|therapists]] and support groups of many kinds attempt to analyze the process. Though there are many theories of romantic love such as that of [[Robert Sternberg]] in which it is merely a mean combining liking and sexual desire, the major theories involve far more insight. For most of the 20th century, Freud's theory of the family drama dominated theories of romance and sexual relationships. This has given rise to a few counter-theories. Theorists like Deleuze counter Freud and [[Lacan]] by attempting to return to a more naturalistic philosophy.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[René Girard]], for example, argues that romantic attraction—not marriage per se—is a product of rivalry, particularly in a triangular form, a view mostly popularized in Girard's theory of mimetic desire, controversial because of its alleged [[sexism]]. The view has to some extent supplanted its predecessor, Freudian Oedipal theory. It may find even some spurious support in the supposed attraction of women to "bad" men, i.e., implying the deflection of male aggression back toward a man and his rival, rather than their beloved. As a technique of attraction, often combined with irony, it is sometimes advised that one feign toughness and disinterest, but it can be a trivial or crude idea to promulgate to men, and it is not given with much understanding of mimetic desire in mind.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Girard, in any case, downplays romance's ''individuality'' in favor of [[jealousy]] and the [[love triangle]], arguing that romantic attraction arises primarily in the ''observed'' attraction between two others. A natural objection is that this is [[circular reasoning]], but Girard means that a small measure of attraction reaches a critical point in so far as it is caught up in mimesis. Shakespeare's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', ''As You Like It'', and ''The Winter's Tale'' are the best known examples.<ref>In works such as ''A Theatre of Envy'' and ''Things Hidden Since the Foundation of The World'', Girard presents this mostly original theory, though finding a major precedent in Shakespeare, on the structure of rivalry, claiming that it, rather than Freud's theory of the primal horde, is the origin of religion and ethics, and all aspects of sexual relations.</ref> Mimetic desire is often challenged by [[feminists]], such as [[Toril Moi]],<ref>The Missing Mother: The Oedipal Rivalries of René Girard. Toril Moi, Diacritics Vol. 12, No. 2, Cherchez la Femme Feminist Critique/Feminine Text (Summer, 1982), pp. 21-31</ref> who argue that it does not account for the woman as inherently desired.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Though the centrality of rivalry is not itself a cynical view, it does emphasize the mechanical in love relations. In that sense, it does resonate with capitalism and a cynicism native to post-modernity. Romance, in this context, for example, leans more on fashion and irony, though these were important for it in less emancipated times. [[Sexual revolution]]s have brought change to these areas. Wit or irony therefore ecompass an instability of romance that is not entirely new but has a more central social role, fine-tuned to certain modern peculiarities and subversion originating in various social revolutions, culminating mostly in the 1960's.<ref>A contemporary irony toward romance is perhaps the expression "throwing game" or simply game. In Marxism the romantic might be considered an example of alienation.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The process of courtship also contributed to [[Schopenhauer]]'s pessimism, despite his own romantic success,<ref>''Essays and Aphorisms''</ref> and he argued that to be rid of the challenge of courtship would drive people to suicide with boredom. Individuals seek partners who share certain interests and tastes, while at the same time looking for a "complement" or completing of themselves in a partner, in the cliché that "opposites attract."

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Romance and value==

| |

| − | Even though there often appears to be traces of romance and love being intertwined in various cultures and socities throughout history, [[Gary Zukav]], best selling author of Seat of the Soul and Soul Stories, views romantic love as being an illusion, stating that the concept of romantic love can never be truly fulfilling. He states that "Romance is your desire to make yourself complete through another person rather than through your own inner work.," thusly isolating the idea of romance from the concept of "true love." His argument is that "real love" is more beneficial than romantic involvement alone. <ref>Soul Stories, Gary Zukav—Note: This quotation and or source may be partially or completely inaccurate.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Romantic love may, then, be a [[human sexual behavior|sexual]] [[love]]<ref>"Sexual" is a loaded term, and "spiritual" is vague. By saying romance is always a form of sexual love, it is meant that while it tries to transcend these things, it never escapes their inclusion entirely and it proceeds, either in some sense ''away'' from these things in terms of origin, or ''toward'' them as in some sense subordinate to sex as a goal, though drawn to mental and spiritual qualities.</ref> that attempts to transcend, in some cases entirely, mere needs driven by physical appearances, [[lust|sexual desire]], or material and social gain. This transcending, ultimately, implies not just that personality is more essential, which could be considered a [[truism]], and a view that might appear without much regard to virtue, ranging from the noble to the most shallow character. Rather, romance tends to strive to see, or suppose it can see, personality as attractive in a fundamentally higher ''sense.'' In some religions, all forms of love (and art) may be regarded as indirectly seeking God—and therefore adding to a relationship with God—whereas at the same time, such lesser objects of love are sometimes regarded as distinct from God and an obstacle in the path of spirituality.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Not only theologians, but many philosophers debate this, especially in continental philosophy in [[existentialism]], and in analytic philosophy, in views such as [[emotivism]].<ref>After the emotivist turn in philosophy, in other words, there was a pressure to reduce moral judgment to some kind of aesthetic judgment. Romantic love moves beyond bodily things on a certain assumption. In other words, any palpable aspect of the person can be cynically chalked up to appearance. What is assumed is not merely that personality is ''of value'' in a more profound sense than the body. (This is a truism easy to defend given the obvious fact of the mind as the most complicated aspect of the person and where he or she is encountered in the most distinctive and compelling way). Rather, the critical assumption is that the personality is ''attractive'' in a fundamentally ''different'' sense from the body as well. This, then is the question of spirituality in romance, taking into account many religious, philosophical and historical views. For example, in realizing that romantic love can never be inherently spiritual, one supposedly passes to a higher spiritual plane, beyond the worldly, which Buddhism may answer with the notion of [[anatman]].</ref> Things lesser than personality, however, as well as the practical aspects of personality, always play a role in romance's arousal and justification.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Romance then, raises questions of [[emotivism]] (or in a more pejorative sense, [[nihilism]]) such as whether spiritual attraction, of the world, might not actually rise above or distinguish itself from that of the body or aesthetic sensibility. While [[Buddha]] taught a philosophy of [[compassion]] and love, still in his philosophy of [[anatman]] or non-self spiritual appearances are of a piece with the world and essentially empty. The contradiction between compassion and anatman seems to be a part of Buddhism. In that case a seemingly negative insight can result in very different overall views, for example if one compares Buddha and Shakespeare with Nietzsche. [[Kierkegaard]] also addressed these ideas in works such as ''Either/Or'' and ''Stages on Life's Way.''<ref>"In the first place, I find it comical that all men are in love and want to be in love, and yet one never can get any illumination upon the question what the lovable, i.e., the proper object of love, really is." (''Stages'' p. 48). Nietzsche, while he might answer negatively to the Platonic theory of love as having a transcendent object, being a [[naturalism(philosophy)|naturalist]], was more interested intellectually in marriage than in romance, as evinced by the many aphorisms on marriage in ''Human All Too Human''. In any case, Nietzsche is often taken as diammetrically opposed to Kierkegaard, of whom there is often supposed mention in ''Thus Spake Zarathustra'' alongside [[Leo Tolstoy]]. (Shakespeare raises a similar criticism about the meaning of love in ''Measure for Measure'', and ''Love's Labors Lost'' is often considered Shakespeare's encomium on love.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Romantic love is contrasted with Platonic love which in all usages precludes sexual relations, yet only in the modern usage does it take on a fully [[asexual]] sense, rather than the classical sense in which sexual drives are sublimated. [[Sublimation]] tends to be forgotten in casual thought about love aside from its emergence in psychoanalysis and Nietzsche. (For an account of the way the modern usage of this term is distinguished from its original sense involving sublimation, see the article [[Platonic love]].) [[Unrequited love]] can be romantic, if only in a comic or tragic sense, or in the sense that sublimation itself is comparable to romance, where the spirituality of both art and egalitarian ideals is combined with strong character and emotions. This situation is typical of the period of [[Romanticism]], but that term is distinct from any romance that might arise within it.<ref>Beethoven, however, is the case in point. He had brief relationships with only a few women, always of the nobility. His one actual engagement was broken off mainly because of his conflicts with noble society as a group. This is evidenced in his biography, such as in Maynard Solomon's account.</ref> Romantic love might be requited emotionally and physically while not being [[consummated]], to which one or both parties might agree.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Tragedy and other social issues of romance==

| |

| − | The ''tragic'' contradiction between romance and society is most forcibly portrayed in Tolstoy's ''[[Anna Karenina]]'', in Flaubert's ''[[Madame Bovary]]'', and of course ''Romeo and Juliet.'' The female protagonists in such stories are driven to suicide as if dying for a cause of freedom from various oppressions of marriage. Even after sexual revolutions, on the other hand, to the extent that it does not lead to procreation (or child-rearing, as it also might exist in [[same-sex marriage]]), romance remains peripheral, though it may have virtues in the relief of [[stress]], as a source of inspiration or adventure, or in development and the strengthening of certain social relations. It is difficult to imagine such tragic heroines, however, as having such practical considerations in mind.

| |

| − | | |

| − | "Romantic," as implied above, has both the connotations of [[courtly love]] and urgent, mutual physical desire, or both spirituality and superficiality. A parallel division occurs in marriage, where sexual relations prepare for and harmonize with later responsibilities.<ref> see [[Alex Comfort]].</ref> In marriage this combination is considered potentially harmonious, whereas in romance taken by itself the role of spirituality tends to be discordant. The synonymous "erotic" has a more unequivocal connotation.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Reciprocity of the sexes appears in the ancient world primarily in myth (where it is in fact often the subject of tragedy, for example in the myths of [[Theseus]] and [[Atalanta]]). Noteworthy female freedom or power was then the exception rather than the rule, though this is a matter of speculation and debate.<ref>Cf. Hegel's Philosophy of History, or womenintheancientworld.com.</ref> At the same time Christianity has had another effect on romance, by asserting the spirituality of marriage.<ref>Catechism of the Catholic Church</ref> This is at least slightly ironic, since religion is the origin of much liberation and emancipation.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Later modern philosophers such as [[La Rochefoucauld]], [[Hume]] and [[Rousseau]] also focused on [[morality]], but desire was central to French thought, and Hume himself tended to adopt a French worldview and temperament. Desire in this milieu meant a very general idea termed "the passions," and this general interest was distinct from the contemporary idea of "passionate" now equated with "romantic." Love was a central topic again in the subsequent movement of [[Romanticism]], which focused on such things as absorption in nature and the [[absolute]], as well as [[Platonic]] and unrequited love in German philosophy and literature.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Philosophers and authors interested in the nature of love, which may not have been mentioned in this article are [[Jane Austen]], [[Stendhal]], [[Schopenhauer]], [[George Meredith]], [[Proust]], [[D.H. Lawrence]], [[Freud]], [[Sartre]], [[de Beauvoir]], [[Hemingway]], [[Henry Miller]], [[Deleuze]], and [[Alan Soble]].

| |

| | | | |

| | ==Notes== | | ==Notes== |

| Line 88: |

Line 41: |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | *[[Alberoni, Francesco]], ''Falling in Love.'' Random House Inc (T); 1st American ed edition (December 1983). ISBN 978-0394530079. | + | * [[Alberoni, Francesco]]. ''Falling in Love.'' Random House Inc (T); 1st American ed edition, 1983. ISBN 978-0394530079 |

| − | *Kierkegaard, Søren. ''Stages on Life's Way : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 11''. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition (November 1, 1988). ISBN 978-0691020495. | + | * Kierkegaard, Søren. ''Stages on Life's Way: Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 11''. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition, 1988. ISBN 978-0691020495 |

| − | *Levi-Strauss, Claude. ''Structural Anthropolgy.'' Basic Books; New Ed edition (January 2000). ISBN 978-0465095162. | + | * Levi-Strauss, Claude. ''Structural Anthropolgy.'' Basic Books; New Ed edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0465095162 |

| − | *Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics). Dover Publications; Dover Ed edition (January 20, 2006). ISBN 978-0486445663. | + | * McWilliams, Peter. ''Love 101: To Love Oneself Is the Beginning of a Lifelong Romance''. Prelude Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931580727 |

| − | *Denis de Rougemont, ''Love in the Western World.'' Schocken (January 27, 1990). ISBN 978-0805209501. | + | * Nietzsche, Friedrich. ''Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics)''. Dover Publications; Dover Ed edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0486445663 |

| | + | * Rougemont, Denis de. ''Love in the Western World.'' Schocken, 1990. ISBN 978-0805209501 |

| | + | * Schopenhauer, Arthur. '' Essays and Aphorisms''. Penguin Classics, 1973. ISBN 978-0140442274 |

| | + | |

| | + | ==External Links== |

| | + | All links retrieved December 15, 2022. |

| | + | |

| | + | *[http://www.livescience.com/health/050531_love_sex.html Love More Powerful than Sex, Study Claims] by Robert Roy Britt, LiveScience Senior Writer (posted: May 31, 2005) ''www.livescience.com'' |

| | + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/l/love.htm The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Philosophy of Love] ''www.iep.utm.edu'' |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] |

| | {{Credit|153789001}} | | {{Credit|153789001}} |

"Romantic love" refers to the connection between "love" and the general idea of "romance," according to more traditional usages of the terms. Historically the term "romance" did not necessarily imply love relationships, but rather was seen as an artistic expression of one's innermost desires; sometimes including love, sometimes not.

The romantic love of knights and damsels, called courtly love, emerged in the early medieval ages (eleventh century France), derived from Platonic, Aristotelian love, and the writings of the Roman poet, Ovid (and his ars amatoria). Such romantic love was often portrayed as not to be consummated, but as transcendentally motivated by a deep respect for the lady and earnestly pursued in chivalric deeds rather than through sexual relations.[1]

Today, romance is still sometimes viewed as an expressionistic or artful form, but within the context of "romantic" relationships it usually implies an active expression of one's love, or one's deep emotional desires to connect with another person intimately with no promise for lasting commitment or marriage. It is often an exaggerated or decorated expression of love.[2] "Romance" in this sense can therefore be defined as attachment, fascination, or enthusiasm for someone of the opposite sex.

Etymology

The English word "romance" developed from a vernacular dialect within the French language, meaning "verse narrative," referring to the style of speech and writing, and artistic talents within elite classes. The word derives from the Latin "Romanicus," meaning "of the Roman style," of "from Rome." European medieval vernacular tales were usually about chivalric adventure, not combining with the theme of love until late into the seventeenth century. The word "romance" also has developed with various meanings in other languages, such as the early nineteenth century Spanish and Italian definitions of "adventure" and "passion," sometimes combining the idea of a "love affair" or "idealistic quality."

The more current and Western traditional terminology meaning a particularly ardent type of love, often transcending moral limits, is believed to have originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily in the French culture. This idea is what has spurred the connection between the words "romantic" and "lover," thusly creating the English phrase "romantic love" (i.e "loving like the Romans do"). However, the precise origins of such a connection are unknown.

As a literary style, the romantic genre has existed since before 1812. Here, the term "romantic" means "characteristic of an ideal love affair." Romanticism, the artistic and intellectual movement that originated in late eighteenth-century Western Europe. In music, the romantic movement was characterized by the free expression of imagination and emotion, displays of instrumental virtuosity, and experimentation with orchestral form.

History and definition

Courtly love, a term first popularized by Gaston Paris in 1883 and closely related to the concept of romantic love, was a medieval European notion of the ennobling love which found its genesis in the ducal and princely courts of present-day southern France at the end of the eleventh century, and which had a civilizing effect on knightly behavior. In essence, the concept of courtly love sought to reconcile erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent".[3]

Courtly love saw high born women as an ennobling spiritual and moral force, a view that was in opposition to ecclesiastical sexual attitudes. Rather than being critical the mutual desire between men and women as sinful, the poets and bards praised it as the highest good. The Church, on the other hand, saw the purpose of marriage (finally declared a sacrament of the Church at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215) as procreation—with any sexual relations beyond that purpose seen as contrary to Christian values. Thus, romantic love, at the root of courtly love, resembles the modern concept of true love, in which such piety has become much less of an issue, at least in post-Reformation Christianity.

The Last Meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere at Arthur's tomb.

Romantic love distinguishes moments and situations within interpersonal relationships. Initially, the concept emphasized emotions (especially those of affection, intimacy, compassion, appreciation, and general "liking") rather than sexual pleasure. But, romantic love, in the abstract sense of the term, is traditionally referred to as involving a mix of emotional and sexual desire for another person.

Modern romantic love is akin to Aristotle's description of the love two people find in the harmony of each other's virtues—"one soul and two bodies," as he poetically put it. Such love is deemed to be of a high status, ethically, aesthetically, and even metaphysically, compared to mere sexual intimacy. Within an existing relationship romantic love can be defined as a temporary freeing or optimizing of intimacy, either in a particularly luxurious manner (or the opposite as in the "natural"), or perhaps in greater spirituality, irony, or peril to the relationship.

Romantic love is often contrasted to marriages of political or economic conveniences, especially arranged marriages in which a woman feels trapped in a relationship with an unattractive or abusive husband. The cultural traditions of marriage and betrothal are often in conflict with the spontaneity and absolute quality of romance. However it is possible that romance and love can exist between the partners within those customs.

The tragic contradictions between romance and society are forcibly portrayed in such examples as the Arthurian story of Lancelot and Guinevere, Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Flaubert's Madame Bovary, and Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. The protagonists in these stories were driven to tragedy by forces seemingly outside of their control, within the context of a romantic love which cannot be fulfilled. Alternatively, these lovers may be seen as going beyond the bounds of the original ideal of romantic love—in which the lovers were meant to express only a spiritual but not sexual love unless they could be married—but fulfilling the modern concept of romantic love which transcends moral boundaries and seeks fulfillment even at the risk of one's life.

Pessimistic views

Romantic love is sometimes directly compared with Platonic love alone, which precludes sexual relations. In certain modern usages it also takes on a fully asexual sense, rather than the classical sense in which sexual drives are (often) sublimated for the sake of or instead of marriage. Unrequited love can be romantic, but it too, occurs due to the sublimation or withholding of reciprocal affection, emotion or sex with no concept or possibility of commitment or marriage.

Schopenhauer saw romantic love as no more than a device of nature for reproducing the species. "Once our work is done," he wrote, "the love we had for our mate leaves us and there is nothing we can do about it."[4]

Kierkegaard, a great proponent of marriage and romantic love who never himself married, went a bit further. In a speech about marriage given in his monumental treatise, Either/Or, one of the pseudonymous authors attempts to show that because marriage is fundamentally lacking in passion, the nature of marriage, unlike romance, is in fact and ironically explainable by a man who has experience of neither marriage nor love.

Notes

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alberoni, Francesco. Falling in Love. Random House Inc (T); 1st American ed edition, 1983. ISBN 978-0394530079

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Stages on Life's Way: Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 11. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition, 1988. ISBN 978-0691020495

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropolgy. Basic Books; New Ed edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0465095162

- McWilliams, Peter. Love 101: To Love Oneself Is the Beginning of a Lifelong Romance. Prelude Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931580727

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All-Too-Human: Parts One and Two (Philosophical Classics). Dover Publications; Dover Ed edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0486445663

- Rougemont, Denis de. Love in the Western World. Schocken, 1990. ISBN 978-0805209501

- Schopenhauer, Arthur. Essays and Aphorisms. Penguin Classics, 1973. ISBN 978-0140442274

External Links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.