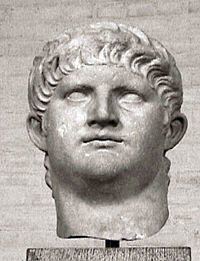

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (December 15, 37 C.E. - June 9, 68 C.E.), born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, also called Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, was the fifth and last Roman Emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (54 C.E. - 68 C.E.). Nero became heir to the then Emperor, his grand-uncle and adoptive father Claudius. As Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus he succeeded to the throne on October 13, 54 C.E., following Claudius's death. In 66 C.E., he added the prefix Imperator to his name. In the year 68 C.E., at thirty-one years old, Nero was deposed. His subsequent death was reportedly the result of suicide assisted by his scribe Epaphroditos.

Popular legend remembers Nero as a pleasure seeker who engaged in petty amusements while neglecting the problems of the Roman city and empire and as the emperor who metaphorically "fiddled while Rome burned." Because of his excesses and eccentricities, he is traditionally viewed as the second of the so-called "Mad Emperors," the first being Caligula. After the Great Fire of Rome in July, 64 C.E. much of the population blamed Nero for failing to control the fire. In retaliation, Nero began to persecute Christians. He ordered that Christians were to be arrested and sentenced to be eaten by lions in public arenas, such as the Colosseum, for the entertainment of the common people. Early Christians considered him an anti-Christ. This form of persecution continued more or less unchecked until Constantine the Great legalized Christianity in 313 C.E..

Rome's earlier Emperors (technically Rome's first citizens) rose to power on the backs of great deeds. Nero, like Caligula, obtained power by the privilege of his birth. Born into great wealth and luxury with little training in administration, a life of indolence was probable for Nero. He was, in a sense, a victim of his own elite status. Perhaps power is best obtained through merit, not blood.

Life

Overview

Nero ruled from 54 C.E. to 68 C.E. During his reign, he focused much of his attention on diplomacy and increasing the cultural capital of the empire. He ordered the building of theaters and promoted athletic games. He also banned the killing of gladiators.

His reign had a number of successes including the war and negotiated peace with the Parthian Empire (58 C.E. - 63 C.E.), the putting down of the British revolt (60 C.E.-61 C.E.), the putting down of a revolt in Gaul (68 C.E.), and improving diplomatic ties with Greece.

His failures included the Roman fire of 64 C.E., the Spanish revolt of 68 C.E. (which preceded his suicide), and the civil war that ensued from his death.

Family

Born in Antium, near Rome, on December 15, 37 C.E., Nero was the only son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Agrippina the Younger, sister and reputed lover of Caligula.

Nero's great-grandparents were Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Aemilia Lepida and their son,Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, was Nero's paternal grandfather. He was also great-grandson to Mark Antony and Octavia Minor through their daughter Antonia Major. Also, through Octavia, he was the great-nephew of Caesar Augustus.

His mother was the namesake of her own mother Agrippina the Elder, who was granddaughter to Octavia's brother Caesar Augustus and his wife Scribonia through their daughter Julia the Elder and her husband Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. His maternal grandfather Germanicus was himself grandson to Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia, adoptive grandson to her second husband Caesar Augustus, nephew and adoptive son of Tiberius, son of Nero Claudius Drusus through his wife Antonia Minor (sister to Antonia Major), and brother to Claudius.

Rise to power

Birth under Caligula

When Nero was born, he was not expected to become Augustus (a title that is honorific of the first citizen). His maternal uncle Caligula had only started his own reign on March 16 of that year at the age of twenty-four. His predecessors Augustus and Tiberius had lived to become seventy-six and seventy-nine respectively. It was presumed that Caligula would produce his own heirs.

Nero (at the time called Lucius) came to the attention of his uncle soon after his birth. Agrippina reportedly asked her brother to name the child. This would be an act of favor and would mark the child as a possible heir to his uncle. However, Caligula only offered to name his nephew Claudius, after their lame and stuttering uncle, apparently implying that he was as unlikely to become Augustus as Claudius.

The relationship between brother and sister soon improved. A prominent scandal early in Caligula's reign was his particularly close relationship with his three sisters, Drusilla, Julia Livilla, and Agrippina. All three are featured with their brother on the Roman currency of the time. The three women seem to have gained his favor and likely some amount of influence. The writings of Flavius Josephus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius report on their reputed sexual relationship with their brother. Drusilla's sudden death in 38 C.E. only served to ensure this belief: she was reportedly Caligula's favorite and was consequently buried with the honors of an Augusta. Caligula proceeded to have her deified, the first woman in Roman history to achieve this honor.

Lucius's mother became known as an influential and prominent woman, although her brother would soon remove her from this distinguished position. Caligula had remained childless. His closest male relatives at the time were his brothers-in-law Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (husband of Drusilla), Marcus Vinicius (husband of Livilla), and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (husband of Agrippina). They were the likely heirs should Caligula die early. However, after the death of his wife, Lepidus apparently lost his chances, though not his ambitions, to succeed his brother-in-law.

Conspiracies

In September 39 C.E. Caligula left Rome with an escort, heading north to join his legions in a campaign against the Germanic tribes. The campaign had to be postponed to the following year due to Caligula's preoccupation with a conspiracy against him. Reportedly Lepidus had managed to become lover to both Agrippina and Livilla, apparently seeking their help in gaining the throne. Consequently, he was immediately executed. Caligula also ordered the execution of Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, the popular Legate of Germania Superior, and his replacement with Servius Sulpicius Galba. However, it remains uncertain whether he was connected to Lepidus' conspiracy. Agrippina and Livilla were soon exiled to the Pontian islands. Lucius was presumably separated from his mother at this point.

Lucius's father died from the effects of edema in 40 C.E. Lucius was now effectively an orphan with an uncertain fate under the increasingly erratic Caligula. However, his luck would change again the following year. On January 24, 41 C.E. Caligula, his wife Caesonia, and their infant daughter Julia Drusilla were murdered due to a conspiracy under Cassius Chaera. The Praetorian Guard helped Claudius gain the throne. Among Claudius's first decisions was the recalling of his nieces from exile.

Agrippina was soon married to the wealthy Gaius Sallustius Crispus Passienus. He died sometime between 44 C.E. and 47 C.E., and Agrippina was reportedly suspected of poisoning him in order to inherit his fortune. Lucius was the only heir to his now-wealthy mother.

Adoption by Claudius

At ten years old, Lucius was still considered an unlikely choice for heir to the throne. Claudius, fifty-seven years old at the time, had reigned longer than his predecessor and arguably more effectively. Claudius had already been married three times. He had married his first two wives, Plautia Urgulanilla and Aelia Paetina, as a private citizen. He was married to Valeria Messalina at the time of his accession. He had two children by his third wife, Claudia Octavia (b. 40 C.E.) and Britannicus (b. 41 C.E.). Messalina was still likely to produce more heirs.

However, in 48 C.E. Messalina was executed , accused of conspiring against her husband. The ambitious Agrippina soon set her sights upon replacing her deceased aunt. On January 1, 49 C.E. she became the fourth wife of Claudius. The marriage would last for five years.

Early in the year 50 C.E. the Roman Senate offered Agrippina the honorable title of Augusta, previously only held by Livia (14 C.E.- 29 C.E.). On February 25, 50 Lucius was officially adopted by Claudius as Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus. Nero was older than his adoptive brother Britannicus and effectively became heir to the throne at the time of his adoption.

Claudius honored his adoptid son in several ways. Nero was proclaimed an adult in 51 C.E. at the age of fourteen. He was appointed proconsul, entered and first addressed the Senate, made joint public appearances with Claudius, and was featured in coinage. In 53 C.E., at the age of sixteen, he married his adoptive sister Claudia Octavia.

Emperor

Becoming Augustus

Claudius died on October 13, 54 C.E., and Nero was soon established as Augustus in his place. It is not known how much Nero knew or was involved with the death of Claudius, but Suetonius, a relatively well-respected Roman historian, wrote:

- ...even if [Nero] was not the instigator of the emperor's death, he was at least privy to it, as he openly admitted; for he used afterward to laud mushrooms, the vehicle in which the poison was administered to Claudius, as "the food of the gods, as the Greek proverb has it." At any rate, after Claudius' death he vented on him every kind of insult, in act and word, charging him now with folly and now with cruelty; for it was a favorite joke of his to say that Claudius had ceased "to play the fool among mortals,." Nero disregarded many of [Claudius's] decrees and acts as the work of a madman and a dotard.

Nero was seventeen years old when he became emperor, the youngest Rome had seen. Historians generally consider Nero to have acted as a figurehead early in his reign. Important decisions were likely to have been left to the more capable minds of his mother Agrippina the younger (who Tacitus claims poisoned Claudius), his tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca, and the praefectus praetorianus Sextus Afranius Burrus. The first five years under Nero became known as examples of fine administration, even resulting in the coinage of the term "Quinquennium Neronis."

The matters of the Empire were handled effectively and the Senate enjoyed a period of renewed influence in state affairs. However, problems soon arose from Nero's personal life and the increasing competition for influence among Agrippina and the two male advisers. Nero was reportedly unsatisfied with his marriage and tended to neglect Octavia. He entered into an affair with Claudia Acte, a former slave. In 55 C.E., Agrippina attempted to intervene in favor of Octavia and demanded that her son dismiss Acte. Burrus and Seneca, however, chose to support their Nero's decision.

Nero resisted the intervention of his mother in his personal affairs. With her influence over her son declining, Agrippina turned her attention to a younger candidate for the throne. Fifteen-year-old Britannicus was still legally a minor under the charge of Nero but was approaching legal adulthood. Britannicus was a likely heir to Nero and ensuring her influence over him could strengthen her position. However, the youth died suddenly and suspiciously on February 12, 55 C.E., the very day before his proclamation as an adult had been set for. According to Suetonius,

- [Nero] attempted the life of Britannicus by poison, not less from jealousy of his voice (for it was more agreeable than his own) than from fear that he might sometime win a higher place than himself in the people's regard because of the memory of his father. He procured the potion from an arch-poisoner, one Locusta, and when the effect was slower than he anticipated, merely physicking Britannicus, he called the woman to him and flogged her with his own hand, charging that she had administered a medicine instead of a poison; and when she said in excuse that she had given a smaller dose to shield him from the odium of the crime, he replied: "It's likely that I am afraid of the Julian law;" and he forced her to mix as swift and instant a potion as she knew how in his own room before his very eyes. Then he tried it on a kid, and as the animal lingered for five hours, had the mixture steeped again and again and threw some of it before a pig. The beast instantly fell dead, whereupon he ordered that the poison be taken to the dining-room and given to Britannicus. The boy dropped dead at the very first taste, but Nero lied to his guests and declared that he was seized with the falling sickness, to which he was subject, and the next day had him hastily and unceremoniously buried in a pouring rain.

Matricide

Agrippina's power soon further declined while Burrus and Seneca jointly became the most influential men in Rome. While his advisers took care of affairs of state, Nero surrounded himself with a circle of favorites. Roman historians report nights of drunken revelry and violence while more mundane matters of politics were neglected. Among his new favorites was Marcus Salvius Otho. By all accounts Otho was as dissolute as Nero but served as a good and intimate friend to him. Some sources even consider them to be lovers. Otho early introduced Nero to one particular woman who would marry first the favorite (Otho) and then the Emperor: Poppaea Sabina, described as a woman of great beauty, charm, and wit. Gossip of Nero, Otho, and Poppaea each forming parts of a love triangle can be found in numerous sources (Plutarch Galba 19.2–20.2; Suetonius Otho [1] -2; Tacitus two versions: Histories [2]; Annals [3]-46; and Dio Cassius Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag; [4]; [5]) Over the years, this turned to a legend that Nero had fiddled as Rome burned, an impossible act as the fiddle had not yet been invented. These and other accounts also depict him as not being in the city at the time (instead he was vacationing in his native Antium), rushing back on hearing news of the fire, and then organizing a relief effort (opening his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless and arranging for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors).

It is entirely unknown who or what actually was the cause of the fire. Ancient sources and scholars favor Nero as the arsonist, but massive accidentally started fires were common in ancient Rome and this was probably no exception.

At the time, the confused population searched for a scapegoat and soon rumors held Nero responsible. The motivation attributed to him was intending to immortalize his name by renaming Rome to "Neropolis." Nero had to engage in scapegoating of his own and chose for his target a small Eastern sect called the Christians. He ordered known Christians to be thrown to the lions in arenas, while others were crucified in large numbers.

Gaius Cornelius Tacitus described the event:

- "And so, to get rid of this rumor, Nero set up [i.e., falsely accused] as the culprits and punished with the utmost refinement of cruelty a class hated for their abominations, who are commonly called Christians. Nero’s scapegoats were the perfect choice because it temporarily relieved pressure of the various rumors going around Rome. Christus, from whom their name is derived, was executed at the hands of the procurator Pontius Pilate in the reign of Tiberius. Checked for a moment, this pernicious superstition again broke out, not only in Iudaea, the source of the evil, but even in Rome... Accordingly, arrest was first made of those who confessed; then, on their evidence, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much on the charge of arson as because of [their] hatred for the human race. Besides being put to death they were made to serve as objects of amusement; they were clothed in the hides of beasts and torn to death by dogs; others were crucified, others set on fire to serve to illuminate the night when daylight failed. Nero had thrown open his grounds for the display, and was putting on a show in the circus, where he mingled with the people in the dress of charioteer or drove about in his chariot. All this gave rise to a feeling of pity, even towards men whose guilt merited the most exemplary punishment; for it was felt that they were being destroyed not for the public good but to gratify the cruelty of an individual." - Tacitus, [6]

The last sentence may be a rhetorical construct of the author designed to further damn Nero, rather than reportage of actual Roman sympathy for the Christians, which seems unlikely to many historians. Whichever is the case, Nero lost his chances at redeeming his reputation and fully quashing the rumors of his starting the fire when he immediately produced plans of rebuilding Rome in a monumental – and less flammable – style; his famous Domus Aurea ("Golden House") was part of his rebuilding plan.

Nero the artist and the Olympic Games

[Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Nero in ancient literature

Classical sources

- Annals (Tacitus)

- Suetonius' Lives of the Twelve Caesars

- Dio Cassius (Books 61 & 63)

- Philostratus II Life of Apollonius Tyana (Books 4 & 5)

Talmud

A Jewish legend contained in the Talmud (tractate Gittin 56B) claims that Nero shot four arrows to the four corners of the earth, and they fell in Jerusalem. Thus he realized that the God had decided to allow the Temple to be destroyed. He also requested a Jewish religious student to show him the Bible verse most appropriate to that situation, and the young boy read to Nero Ezekiel's prophecy about God's revenge on the nation of Edom ([7]) for their destruction of Jerusalem. Nero thus realized that the Lord would punish him for destroying his Temple, so he fled Rome and converted to Judaism, to avoid such retribution. In this telling, his descendant is Rabbi Meir, a prominent supporter of Bar Kokhba's rebellion against Roman rule (132 C.E.-135 C.E.).

New Testament

Many scholars, such as Delbert Hillers (John Hopkins University) of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the editors of the Oxford & Harper Collins translations, contend that the number 666 in the Book of Revelation is a code for Nero[8], a view that is also supported by the Roman Catholic Church [9] [10]. In Ancient Greek, the language of the New Testament, Nero was referred to as Neron Caesar, which has the numerical value of 666.

Later Christian writers

Sibylline Oracles, Book 3, allegedly written before Nero's time, prophesies anti-Christ and identifies him with Nero. However, it was actually written long after him and this identification was in any case rejected by Irenaeus in Against Heresies, Book 5, 27–30. They represent the mid-point in the change between the New Testament's identification of the past (Nero) or current (Domitian) antichrist, and later Christian writers' concern with the future anti-Christ. One of these later writers is Commodianus whose Institutes, 1.41, states that the future anti-Christ will be Nero returned from hell.

Nero in medieval literature

Usually as a stock exemplar of vice or a bad ruler

- In the Golden Legend, and its apocryphal account of his forcing Seneca the Younger's suicide, where they meet face to face on this occasion.

- In Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, 'The Monk's Prologue and Tale'

- Giovanni Boccaccio's Concerning the Falls of Illustrious Men

- Surprisingly, he does not seem to appear in Dante Alighieri's Inferno

Nero in modern culture

Literature and film/TV adaptations

- Nero's rule is described in the novel Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz. In the 1951 film version, Nero is played by actor Peter Ustinov.

- Nero is a major character in the play and film "The Sign of the Cross," which bears a strong resemblance to Quo Vadis.

- Nero appears in Robert Graves' books I, Claudius and Claudius the God (and the BBC miniseries adapted from the book, played by Christopher Biggins]), which is a fictional autobiography of the Emperor Claudius.

- Nero's life, times and death are chronicled in Richard Holland's book of the same name - NERO The Man Behind The Myth.

- In the film version of Philip José Farmer's Riverworld series of novels, Nero takes the place of the book's principal villain King John of England. Nero was portrayed by English actor Jonathan Cake.

- Federico Fellini's film Satyricon portrays life in the time of the rule of Nero.

- Nero is a character in the novel The Light Bearer by Donna Gillespie.

Notes

- ↑ The Life of Otho. C. Suetonius Tranquillus #3 iii.1Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ 1.13.3. Tacitus, The History BOOK I: JANUARY—MARCH, AD 69. Tufts University-4Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ BOOK XIII A.D. 54—58. Tufts University.45 xiii.45Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Suetonius, Nero xxxvii. C. Suetonius Tranquillus.Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ R.H. lxii. Cassius DioRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Annales, xv.44. Tacitus, The Annals BOOK XV: A.D. 62—65. Tufts UniversityRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Ezekiel Chapter 25. The King James Bible PageRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Hillers, Delbert, “Rev. 13, 18 and a scroll from Murabba’at,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 170 (1963) 65.

- ↑ The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Ed. Raymond E. Brown, Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and Roland E. Murphy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1990. 1009

- ↑ http://catholic-resources.org/Bible/Apocalyptic.htm The Book of Revelation, Apocalyptic Literature, and Millennial Movements, Prof. Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D., University of San Francisco, USF Jesuit Community Retrieved May 14, 2007.

External links

Primary sources

Suetonius. The Lives of the twelve Caesars: Nero

Secondary material

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Life of Nero. C. Suetonius TranquillusRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Books 61‑63Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Ancient History Sourcebook: Suetonius: De Vita Caesarum—Nero, c. 110 C.E. J. C. RolfeRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Data on Nero. Who Was Who in Roman TimesRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Nero (54-68 C.E.). De Imperatoribus RomanisRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Nero. Bible History OnlineRetrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus (AD 15 - AD 68). Illustratd History of the Roman Empire.Retrieved May 14, 2007.