Nefertiti

| Nefertiti in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||||

|

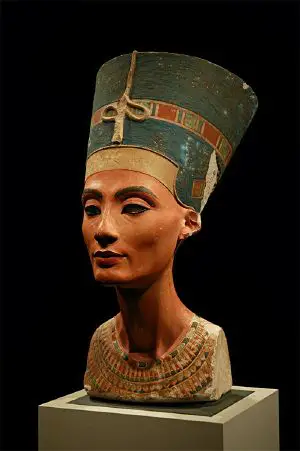

Nefertiti (pronounced at the time something like *nafratiːta[1]) (c. 1370 B.C.E. - c. 1330 B.C.E.) was the Great Royal Wife (or chief consort/wife) of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. She was the mother-in-law and probable stepmother of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Nefertiti may have also ruled as pharaoh in her own right under the name Ankhkheprure Neferneferuaten. There is also some confusion with the Co-Regent known as Smenkhkare who used the throne name Ankhkheprure Smenkhkare. Some schools of thought believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly after her husband's death and before the accession of Tutankhamun, although this identification is called into doubt by the latest research.[citation needed] Her name roughly translates to "the beautiful (or perfect) one has arrived." She also shares her name with a type of elongated gold bead, called nefer, that she was often portrayed as wearing. She was made famous by her bust, now in Berlin's Altes Museum, shown to the right. The bust is one of the most copied works of ancient Egypt. It was attributed to the sculptor Thutmose, and was found in his workshop. The bust itself is notable for exemplifying the understanding Ancient Egyptians had regarding realistic facial proportions. She had many titles; for example, at Karnak there are inscriptions that read Heiress, Great of Favours, Possessed of Charm, Exuding Happiness, Mistress of Sweetness, beloved one, soothing the king's heart in his house, soft-spoken in all, Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt, Great King's Wife, whom he loves, Lady of the Two Lands, Nefertiti'.

Nefertiti and her husband were known for changing Egypt's religion from a polytheistic religion to a monotheistic religion. They believed only in one god, Aten.

Nefertiti was also known throughout Egypt for her beauty. She was very proud of her long, swan like neck. She even invented her own makeup using the Galena plant.

Family

Nefertiti's parentage is not known with certainty, but it is now generally believed that she was the daughter of Ay, later to be pharaoh and the sister of Moutnemendjet.[2] Another theory that gained some support identified Nefertiti with the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa. The name Nimerithin has been mentioned in older scrolls, as an alternative name, but this has not yet been officially confirmed.

The exact dates of when Nefertiti was married to Amenhotep IV and later promoted to his Queen are uncertain. However, the couple had six known daughters. This is a list with suggested years of birth:

- Meritaten: Before year one or the very beginning of year one.(1356 B.C.E.).

- Meketaten: Year 1 or three (1349 B.C.E.).

- Ankhesenpaaten, also known as Ankhesenamen, later queen of Tutankhamun

- Neferneferuaten Tasherit: Year 6 (1344 B.C.E.)

- Neferneferure: Year 9 (1341 B.C.E.).

- Setepenre: Year 11 (1339 B.C.E.).

In Year 4 of his reign (1346 B.C.E.) Amenhotep IV started his worship of Aten. The king led a religious revolution, in which Nefertiti played a prominent role. This year is also believed to mark the beginning of his construction of a new capital, Akhetaten, at what is known today as Amarna. In his Year 5, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten as evidence of his new worship. The date given for the event has been estimated to fall around January 2 of that year. In Year 7 of his reign (1343 B.C.E.) the capital was officially moved from Thebes to Amarna, though construction of the city seems to have continued for two more years (till 1341 B.C.E.). The new city was dedicated to the royal couple's new religion. Nefertiti's famous bust is also thought to have been created around this time.

In an inscription estimated to November 21 of year 12 of the reign (approx. 1338 B.C.E.), her daughter Meketaten is mentioned for the last time; she is thought to have died shortly after that date. Circumstantial evidence which shows that she predeceased her husband at Akhetaten include several shabti fragments of the Queen's burial which are now located in the Louvre and Brooklyn Museums.[3] A relief in Akhenaten's tomb in the Royal Wadi at Amarna appears to show her funeral.

During Akhenaten's reign (and perhaps after) Nefertiti enjoyed unprecedented power, and by the twelfth year of his reign, there is evidence that she may have been elevated to the status of co-regent[4]: equal in status to the pharaoh himself. She was often depicted on temple walls the same size as the king, signifying her importance, and shown worshiping the Aten alone. Perhaps most impressively, Nefertiti is shown on a relief from the temple at Amarna which is now in the MFA in Boston, smiting a foreign enemy with a mace before the Aten. Such depictions had traditionally been reserved for the pharaoh alone, and yet Nefertiti was depicted as such.

Akhenaten had the figure of Nefertiti carved onto the four corners of his granite sarcophagus and it was she who provided the protection to his mummy, a role traditionally played by the female deities Isis, Nephthys, Selket and Neith. [5]

Death

About Year 14 of Akhenaten's reign (1336 B.C.E.), Nefertiti herself vanishes from the historical record, and there is no word of her after that date. Theories include a sudden death by a plague that was sweeping through the city or another natural death. A previous theory that she fell into disgrace is now discredited since the deliberate erasures of the monuments belonging to a queen of Akhenaten has now been shown to refer to Kiya instead.[6] Regardless, the verifiable knowledge of this episode has been completely lost to history.

The Coregency Stela may show her as a co-regent with her husband, who possibly ruled after his death, it is thought by some scholars that Nefertiti changed her name to Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, a conjectural pharaoh who may have been the one responsible for abandoning the Aten religion, and moving the capital back to Thebes. This would have been the only way to please both the people and the powerful priests of Amun. Nefertiti would have prepared for her death and for the succession of her daughter, now named Ankhsenamun, and her stepson, Tutankhamun. They would have been educated in the traditional way, worshiping the old gods. This theory has Neferneferuaten dying after two years of kingship and was then succeeded by Tutankhamun, thought to have been a son of Akhenaten. He married Nefertiti's daughter Ankhesenpaaten. The royal couple were young and inexperienced, by any estimation of their age, and Ankhesenpaaten bore two stillborn (and premature) daughters whose mummies were found by Howard Carter in Tutankhamen's tomb.

Some theories believe that Nefertiti was still alive and held influence on the younger royals. If this is the case, that influence and presumably Nefertiti's own life would have ended by year 3 of Tutankhaten's reign (1331 B.C.E.). In that year, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun, as evidence of his return to the official worship of Amun, and his abandonment of Amarna to return the capital to Thebes.

As can be seen by the suggested identifications between Tadukhipa, Nefertiti, Smenkhkare and Kiya, the records of their time and their lives are largely incomplete, and the findings of both archaelogists and historians may develop new theories vis-à-vis Nefertiti and her precipitous exit from the public stage.

Burial

No concrete information is available regarding Nefertiti's death, but the location of Nefertiti's body has long been a subject of curiosity and speculation. There are many theories regarding her death and burial.

The "Younger Lady"

In the most recent research effort led by Egyptian archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass, head of Egypt's Supreme Council for Antiquities, a mummy known as the "The Younger Lady" was put through CT scan analysis and researchers concluded that she may be Tutankhamun's biological mother, Queen Kiya, not Queen Nefertiti. Fragments of shattered bone were found in the sinus, and blood clots were found, so the theory that the damage was inflicted post-mummification was rejected and a murder scenario was deemed more likely. Another reasoning to support Kiya's placement in KV35 is that after Tutankhamun returned Egypt to the traditional religion, he also moved his closest relatives, father, grand mother, and biological mother, to the Valley of the Kings to be buried with him (matching the list of figurines and drawings in his tomb). Nefertiti may still be in an undiscovered tomb.

Previously, on June 9, 2003, archaeologist Joann Fletcher, a specialist in ancient hair from the University of York in England, announced that Nefertiti's mummy may have been one of the anonymous mummies stored in tomb KV35 in the Valley of the Kings known as "the Younger Lady." However, an independent scholar in the field of Egyptology, Marianne Luban, had already made the same speculation as early as 1999 in an article posted on the Internet, entitled "Do We Have the Mummy of Nefertiti?"[7]

Luban's points upholding the identification are the same as those of Joann Fletcher. Furthermore, Fletcher suggested that Nefertiti was in fact the Pharaoh Smenkhkare. Some Egyptologists hold to this view though the majority believe Smenkhkare to have been a separate person. Dr. Fletcher led an expedition funded by the Discovery Channel that examined what they believed to have been Nefertiti's mummy.

The team claimed that the mummy they examined was damaged in a way suggesting the body had been deliberately desecrated in antiquity. Mummification techniques, such as the use of embalming fluid and the presence of an intact brain, suggested an eighteenth dynasty royal mummy. Other features the team used to support their claims were the age of the body, the presence of embedded nefer beads, and a wig of a rare style worn by Nefertiti. They further claimed that the mummy's arm was originally bent in the position reserved for pharaohs, but was later snapped off and replaced with another arm in a normal position.

However most Egyptologists, among them Kent Weeks and Peter Locavara, generally dismiss Fletcher's claims as unsubstantiated. They claim that ancient mummies are almost impossible to identify with a particular person without DNA; and as bodies of Nefertiti's parents or children have never been identified, her conclusive identification is impossible. Any circumstantial evidence, such as hairstyle and arm position, is not reliable enough to pinpoint a single, specific historical person. The cause of damage to the mummy can only be speculated upon, and the alleged revenge is an unsubstantiated theory. Bent arms, contrary to Fletcher's claims, were not reserved exclusively to pharaohs; this was also used for other members of the royal family. The wig found near to the mummy is of unknown origin, and cannot be conclusively linked to that specific body. Finally, the 18th dynasty was one of the largest and most prosperous dynasties of ancient Egypt, and a female royal mummy could be any of a hundred royal wives or daughters from 18th dynasty's more than 200 years on the throne.

In addition, there is controversy about both the age and gender of the mummy. On June 12, 2003, Hawass also dismissed the claim, citing insufficient evidence. On August 30, 2003, Reuters further quoted Hawass as saying, "I'm sure that this mummy is not a female," and "Dr Fletcher has broken the rules and therefore, at least until we have reviewed the situation with her university, she must be banned from working in Egypt."[8] Hawass has claimed that the mummy is female and male on different occasions.[9]

The Elder Lady?

A KMT article called "Who is The Elder Lady mummy?" suggests that the elder lady mummy may be Nefertiti's body [10]. This may be possible due to the fact that the mummy is around her mid-thirties or early forties, Nefertiti's guessed age of death. Also, unfinished busts of Nefertiti appear to resemble the mummy's face, though other suggestions include Ankhesenamun and, the favorite candidate, Tiye. More evidence to support this identification is that the mummy's teeth look like that of a 29-38 year old, Nefertiti's most likely age of death. Due to recent age tests on the mummy's teeth, it appears that the 'Elder Lady' is in fact Queen Tiye and also that the DNA of the mummy is a close, if not direct, match to the lock of hair found in Tutankhamun's tomb which bears the inscription of Queen Tiye is the hairs coffin. To date, the mummy of this famous and iconic queen has not been found.

Iconic status

Nefertiti's place as an icon in popular culture is secure as she has become somewhat of a celebrity. After Cleopatra she is the second most famous "Queen" of Egypt in the Western imagination and influenced through photographs that changed standards of feminine beauty of the 20th century, and is often referred to as "the most beautiful woman in the world." [11][12]

The character Cortana from the video game Halo: Combat Evolved was originally based on images of Nefertiti.[13] A.I.s from this game's story universe often take the form of mythological or historical characters.

Notes

- ↑ Allen, 2004.

- ↑ Egypt State Information Service - Famous women

- ↑ Dodson and Hilton, 2004, p.156.

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas. 2005, p.172.

- ↑ Queen Nefertiti of Egypt touregypt.net Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Dodson and Hilton, p.156.

- ↑ Do We Have the Mummy of Nefertiti? geocities.com All links retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Hawass comments - No Discrimination zahihawass.com Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Times Online - King Tut tut tut timesonline.co.uk Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ KMT article "Who is Elder Lady" egyptology.com Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Queen Nefertiti of Egypt touregypt.net Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Nefertiti crystalinks.com Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Lorraine Mclees "Halo: Cortana's face was modeled after an Egyptian queen" forums.bungie.org Retrieved November 5, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, James. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs , Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0521774833

- Dodson, Aidan and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 978-0500051283

- Reeves, Nicholas. Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet, Thames & Hudson, 2005. ISBN 0-500-285527

- Reeves, Nicholas and Richard H. Wilkinson. The Complete Valley of the Kings, Thames & Hudson, 2008. ISBN 978-0500284032

- Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt , Oxford University Press, USA, 2004. ISBN 978-0192804587

Template:Ancient Egyptians

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.