Difference between revisions of "Mi'kmaq" - New World Encyclopedia

(→Notes) |

({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Started}}{{Contracted}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

Revision as of 01:18, 26 October 2007

| Mi'kmaq |

|---|

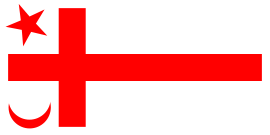

| Míkmaq State flag |

| Total population |

| 40,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec), United States (Maine) |

| Languages |

| English, Míkmaq, French |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Algonquian peoples |

The Mi'kmaq ([miːgmaɣ]; (also spelled Míkmaq, Mi'gmaq, Micmac or MicMac) are a First Nations people, indigenous to northeastern New England, Canada's Atlantic Provinces, and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec. The word Míkmaw is an adjectival form of the plural noun for the people, Míkmaq. Mi'kmaq are self-recognized as L'nu (in the singular; the plural is Lnu'k). (The Nova Scotia Museum's Mi'kmaq Portraits database). The name Mi'kmaq comes from a word in their language meaning "allies."

Population

| Year | Population | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 4.500 | Estimation |

| 1600 | 3.000 | Estimation |

| 1700 | 2.000 | Estimation |

| 1750 | 3.000 | Estimation |

| 1800 | 3.100 | Estimation |

| 1900 | 4.000 | Census |

| 1940 | 5.000 | Census |

| 1960 | 6.000 | Census |

| 1972 | 9.800 | Census |

| 2000 | 20.000 | Estimation |

The pre-contact population is estimated at 35,000. In 1616 Father Biard believed the Mi'kmaq population to be in excess of 3.000. But he remarked that, because of European diseases, there had been large population losses in the last century. Smallpox, wars and alcoholism led to a further decline of the native population, which was probably at its lowest in the middle of the 17th century. Then the numbers grew slightly again and seemed to be stable during the 19th century. In the 20th century the population was on the rise again. The average growth from 1965 to 1970 was about 2.5%.

History

The Mi'kmaq were members of the Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki Confederacy), an alliance with four other Algonquian nations: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. At the time of contact with the French (late 1500s) they were expanding from their Maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /St. Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquioian Mohawk tribes, hence the Mi'kmaq name for this peninsula, Gespedeg ("last-acquired"). In 1610, Chief Membertou concluded their first alliance with Europeans, a concordat with the French Jesuits that affirmed the right of Mi'kmaq to choose Catholicism, Mi'kmaq tradition, or both.

The Mi'kmaq were allies with the French, and were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst. But as France lost control of Acadia in the early 1700s, they soon found themselves overwhelmed by British (English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh) who seized much of the land without payment and deported the French. Between 1725 and 1779, the Mi'kmaq signed a series of peace and friendship treaties with Great Britain, but none of these were land cession treaties. The nation historically consisted of seven districts, but this was later expanded to eight with the ceremonial addition of Great Britain at the time of the 1749 treaty. Later on the Mi'kmaq also settled Newfoundland as the unrelated Beothuk tribe became extinct. Mi'kmaq representatives also concluded the first international treaty with the United States after its declaration of independence, the Treaty of Watertown.

Culture

The spiritual capital of the Mi'kmaq nation is the gathering place of the Mi'kmaq Grand Council, Mniku or Chapel Island in the Bras d'Or Lakes of Cape Breton Island. The island also the site of the St. Anne Mission, an important pilgrimage site for the Mi'kmaq. The island has been declared a historic site.

In the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador October is celebrated as Mi'kmaq History Month and the entire Nation celebrates Treaty Day annually on October 1st. L’nu (Lnu'k - plural form) is the self-recognized term for the Mi'kmaq of New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Maine, United States.

Members of the Mi'kmaq First Nation historically referred to themselves as L'nu, meaning human being.[1] But, the Mi'kmaq's French allies, whom the Mi'kmaq referred to as Ni'kmaq, meaning "my kin," initially referred to the Mi'kmaq, (as is written in Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France) as "Souriquois" (the Souricoua River was a travel route between the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence) or "Gaspesians." Over time their French allies and succeeding immigrating nations’ peoples began to refer to the Lnu'k as Ni’knaq, (invariably corrupting the word to various spellings such as Mik Mak, Mic Mac, etc.) The British originally referred to them as Tarrantines.[2]

With constant use, the term "Micmac" entered the English lexicon, and was used by the Lnu'k as well. Present day Lnu’k linguists have standardized the writing of Lnui'simk for modern times and "Mi’kmaq" is now the official spelling of the name. The name "Quebec" is thought to derive from a Mi'kmaq word meaning "strait," referring to the narrow channel of the Saint Lawrence River near the city site.

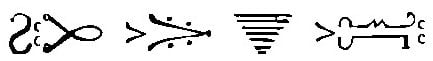

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing was a pictographic writing scheme and memory aid used by the Mi'kmaq.

Technically, the Mi'kmaq system was logographic rather than hieroglyphic, because hieroglyphs incorporate both alphabetic and logographic information. The Mi'kmaq system was entirely logographic.

It has been debated by some scholars whether the original "hieroglyphs" qualified fully as a writing system rather than merely a mnemonic device, before their adaptation for pedagogical purposes in the 17th century by the French missionary Chrétien Le Clercq. Ives Goddard and William Fitzhugh from the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution contended in 1978 that the system was purely mnemonic, because it could not be used to write new compositions. Schmidt and Marshall argued in 1995 that the newly adapted form was able to act as a fully-functional writing system, and did not involve only mnemonic functions. This would mean that the Mi'kmaq system is the oldest writing system for a North American language north of Mexico.

Origins

Father le Clercq, a Roman Catholic missionary on the Gaspé Peninsula from 1675, claimed that he had seen some Mi'kmaq children 'writing' symbols on birchbark as a memory aid. This was sometimes done by pressing porcupine quills directly into the bark in the shape of symbols. Le Clercq adapted those symbols to writing prayers, developing new symbols as necessary. This writing system proved popular among Mi'kmaq, and was still in use in the 19th century. Since there is no historical or archaeological evidence of these symbols from before the arrival of this missionary, it is unclear how ancient the use of the mnemonic glyphs was. The relationship of these symbols with Mi'kmaq petroglyphs is also unclear.

Mi'kmaq First Nation subdivisions

Note: Mi'kmaq names in the table have all been spelled according to a several orthographies; The Mi'kmaq orthographies in use are Míkmaq hieroglyphs, the orthography of Silas Tertius Rand, the Pacifique orthography, and the most recent Smith-Francis orthography, which has been adopted by most of the Mi'kmaq First Nation. (Compare Kespék versus Gespeg).

| Community | Province/State | Town/Reserve | Est. Pop. | Míkmaq name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abegweit First Nation | PE | Scotchfort, Rocky Point, Morell | 396 | Epekwitk |

| Acadia | NS | Yarmouth | 996 | Malikiaq |

| Annapolis Valley | NS | Cambridge Station | 219 | Kampalijek |

| Aroostook Band of Micmac | ME | Presque Isle | 920 | Ulustuk |

| Bear River First Nation | NS | Bear River | 272 | L’setkuk |

| Buctouche First Nation | NB | Buctouche | 80 | Puktusk |

| Burnt Church First Nation | NB | Burnt Church 14 | 1,488 | Esk |

| Chapel Island First Nation | NS | Chapel Island | 576 | Potlotek |

| Eel Ground First Nation | NB | Eel Ground | 844 | Natuaqanek |

| Eel River Bar First Nation | NB | Eel River Bar | 589 | Oqpíkanjik |

| Elsipogtog First Nation | NB | Big Cove | 2,720 | Lsipuktuk |

| Eskasoni First Nation | NS | Eskasoni | 5,000 | Eskisoqnik |

| Fort Folly First Nation | NB | Dorchester | 105 | Amlamkuk Kwesawék |

| Micmacs of Gesgapegiag | QC | Maria | 1,174 | Keskapekiaq |

| Nation Micmac de Gespeg | QC | Fontenelle | 490 | Kespék |

| Glooscap First Nation | NS | Hantsport | ? | Pesikitk |

| Indian Island First Nation | NB | Indian Island | 145 | L’nui Menikuk |

| Lennox Island First Nation | PE | Lennox Island | 700 | L’nui Mnikuk |

| Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation | QC | Listiguj | 3,166 | Listikujk |

| Membertou First Nation | NS | Sydney | 1,051 | Maupeltuk |

| Metepenagiag Míkmaq Nation | NB | Red Bank | 527 | Metepnákiaq |

| Miawpukek First Nation | NL | Conne River | 2,366 | Miawpukwek |

| Millbrook First Nation | NS | Truro | 1000 | Wékopekwitk |

| Pabineau First Nation | NB | Pabineau | 214 | Kékwapskuk |

| Paq’tnkek First Nation | NS | Afton | 489 | Paqtnkek |

| Pictou Landing First Nation | NS | Trenton | 547 | Puksaqtéknékatik |

| Indian Brook First Nation | NS | Shubenacadie | 2,120 | Sipekníkatik |

| Wagmatcook First Nation | NS | Wagmatcook | 623 | Waqm |

| Waycobah First Nation | NS | Whycocomagh | 900 | Wékoqmáq |

Contemporary

The Nation MicMac currently has a population of about 40,000 of whom approximately one-third still speak the Algonquian language Lnuísimk which was once written in Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing and is now written using most letters of the standard Latin alphabet.

Popular Culture

(CBC) The Mi'kmaq (spelled Micmac) are credited as the Indians responsible for the ancient Indian burial ground in Stephen King's Pet Sematary.

Notable Mi'kmaq

- Kevin Cloud

- Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, activist (1946-1976)

- Henri Membertou, kji-saqmaw/puowin (c.1525-1611)

- Rita Joe, poet

- Donald Marshall Jr.

- Chad Denny, Lewiston MAINEiacs defenceman and Atlanta Thrashers draftee

Notes

- ↑ The Nova Scotia Museum's Mi'kmaq Portraits database

- ↑ Lydia Affleck and Simon White. Our Language. Native Traditions. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- Treaty of Watertown

- Bob Newman - radio host and Mi'kmaq

- Elsipogtog First Nation

- Canada Post French Settlement Series

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bock, Philip K. 1978. "Micmac." Pp. 109-122. InHandbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Bruce G. Trigger, editor. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Davis, Stephen A. 1998. Mi'kmaq: Peoples of the Maritimes, Nimbus Publishing.

- Paul, Daniel N. 2000. We Were Not the Savages: A Mi'kmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations, Fernwood Pub.

- Prins, Harald E. L. 1996. The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology), Wadsworth.

- Rita Joe, Lesley Choyce. 2005. The Mi'kmaq Anthology, Nimbus Publishing (CN), 2005, ISBN 1-895900-04-2

- Whitehead, Ruth Holmes. 2004. The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Mi'kmaq History 1500-1950, Nimbus Pub Ltd, 2004, ISBN 0-921054-83-1

- Wicken, William C. 2002. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior, University of Toronto Press.

- Chaisson, Paul, The Island of Seven Cities: where the Chinese settled when they discovered North America, Random House Canada, 2006, p. 170.

- Fell, Barry. 1992. "The Micmac Manuscripts" in Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, 21:295.

- Goddard, Ives, and William W. Fitzhugh. 1978. "Barry Fell Reexamined," in The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 41, No. 3. (September), pp. 85-88.

- Kauder, Christian. 1921. Sapeoig Oigatigen tan teli Gômgoetjoigasigel Alasotmaganel, Ginamatineoel ag Getapefiemgeoel; Manuel de Prières, instructions et changs sacrés en Hieroglyphes micmacs; Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms & Hymns in Micmac Ideograms. New edition of Father Kauder's Book published in 1866. Ristigouche, Québec: The Micmac Messenger.

- Lenhart, John. History relating to Manual of prayers, instructions, psalms and humns in Micmac Ideograms used by Micmac Indians fof Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. Sydney, Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Native Communications Society.

- Schmidt, David L., and B. A. Balcom. 1995. "The Règlements of 1739: A Note on Micmac Law and Literacy," in Acadiensis. XXIII, 1 (Autumn 1993) pp 110-127. ISSN 0044-5851

- Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. 1995. Mi'kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-55109-069-4

Documentary film

- Our Lives in Our Hands (Mi'kmaq basketmakers and potato diggers in northern Maine, 1986) [1]

External links

- First Nations Profiles

- Micmac History

- Mi'kmaq History Month

- Mi'kmaq Portraits Collection

- Mi'kmaq Dictionary Online

- The Micmac of Megumaagee

- Mi'kmaq Portraits Collection Includes tracings and images of Mi'kmaq petroglyphs

- Micmac at ChristusRex.org A large collection of scans of prayers in Mi'kmaq hieroglyphs.

- Écriture sacrée en Nouvelle France: Les hiéroglyphes micmacs et transformation cosmologique (PDF, in French) A discussion of the origins of Mi'kmaq hieroglyphs and sociocultural change in 17th century Micmac society.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.