Difference between revisions of "Mesha Stele" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→External links) |

m |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

== Text in Hebrew == | == Text in Hebrew == | ||

The text, in [[Moabite language|Moabite]], transcribed into modern [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew letters]]: | The text, in [[Moabite language|Moabite]], transcribed into modern [[Hebrew alphabet|Hebrew letters]]: | ||

| − | |||

<div dir="rtl" style="width: 100%;"> | <div dir="rtl" style="width: 100%;"> | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

Revision as of 15:50, 24 September 2008

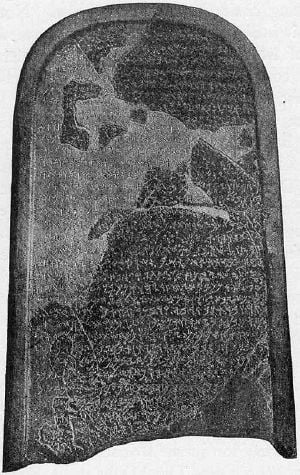

The Mesha Stele (popularized in the 19th century as the "Moabite Stone") is a black basalt stone, bearing an inscription by the 9th century B.C.E. Moabite King Mesha, discovered in 1868 at Dhiban (biblical "Dibon," capital of Moab). The inscription of 34 lines is written in the Moabite language. It is the most extensive inscription ever recovered that refers to ancient Israel. It was set up by Mesha, about 850 B.C.E., as a record and memorial of his victories in his revolt against the Kingdom of Israel, undertaken after the death of his overlord, Ahab.

The stone is 124 cm high and 71 cm wide and deep, and rounded at the top. It was discovered at the ancient Dibon now Dhiban, Jordan, in August 1868, by Rev. F. A. Klein, a German missionary in Jerusalem. "The Arabs of the neighborhood, dreading the loss of such a talisman, broke the stone into pieces; but a squeeze had already been obtained by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, and most of the fragments were recovered and pieced together by him".[8] A squeeze is a papier-mâché impression. The squeeze (which has never been published) and the reassembled stele (which has been published in many books and encyclopedias) are now in the Louvre Museum.

Contents

The stele, which measures 44"x27"[1], describes:

- How Moab was conquered by Omri, King of Israel, as the result of the anger of the god Chemosh. Mesha's victories over Omri's son (not mentioned by name), over the men of Gad at Ataroth, and at Nebo and Jehaz;

- His public buildings, restoring the fortifications of his strong places and building a palace and reservoirs for water; and

- His wars against the Horonaim.

The inscription has strong consistency with the historical events recorded in the Bible. The events, names, and places mentioned in the Mesha Stele correspond to those mentioned in the Bible. For example, Mesha is recorded as the King of Moab in 2 Kings 3:4: “Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep breeder, and he had to deliver to the king of Israel 100,000 lambs and the wool of 100,000 rams.”[2] Kemosh is mentioned in numerous places in the Bible as the national god of Moab (1 Kings 11:33, Numbers 21:29 etc...).[3] The reign of Omri, King of Israel, is chronicled in I Kings 16[4], and the inscription records many places and territories (Nebo, Gad, etc...) that also appear in the Bible.[5] Finally, 2 Kings 3 recounts a revolt by Mesha against Israel, to which Israel responded by allying with Judah and Edom to suppress the revolt:

“4Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep breeder, and he had to deliver to the king of Israel 100,000 lambs and the wool of 100,000 rams. 5But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel. 6So King Jehoram marched out of Samaria at that time and mustered all Israel. 7And he went and sent word to Jehoshaphat king of Judah, "The king of Moab has rebelled against me. Will you go with me to battle against Moab?" And he said, "I will go. I am as you are, my people as your people, my horses as your horses." 8Then he said, "By which way shall we march?" Jehoram answered, "By the way of the wilderness of Edom." 9So the king of Israel went with the king of Judah and the king of Edom…26When the king of Moab saw that the battle was going against him, he took with him 700 swordsmen to break through, opposite the king of Edom, but they could not. 27Then he took his oldest son who was to reign in his place and offered him for a burnt offering on the wall. And there came great wrath against Israel. And they withdrew from him and returned to their own land.”[6]

Some scholars have argued that an inconsistency exists between the Mesha Stele and the Bible regarding the timing of the revolt.[7] The argument rests upon the assumption that the following section of the inscription necessarily refers to Omri’s son Ahab: “Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemosh was angry with his land. And his son replaced him; and he said, "I will also oppress Moab"…And Omri took possession of the whole land of Madaba; and he lived there in his days and half the days of his son: forty years: And Kemosh restored it in my days.” In other words, these scholars argue that the inscription indicates that Mesha’s revolt occurred during the reign of Omri’s son Ahab. Since the Bible speaks of the revolt taking place during Jehoram’s reign (Omri’s grandson), these scholars have argued that these two accounts are inconsistent.

However, as other scholars have pointed out, the inscription need not necessarily refer to Omri’s son Ahab.[8] In modern English, the word “son” typically refers to a male child in relation to his parents. In the ancient Near East, however, the word was commonly used to mean male descendent.[9] Consequently, “son of Omri” was a common designation for any male descendent of Omri and would have been used to refer to Jehoram. Assuming that “son” means “descendent,” an interpretation consistent with the common use of language in the ancient Near East, the Mesha Stele and the Bible are consistent.

With the exception of a very few variations, such as -in for -im in plurals, the Moabite language of the inscription shares much in common with an early form of Hebrew, known as Biblical Hebrew.[10] The language of ninth century B.C.E. Moabite inscriptions is an offshoot of the Canaanite language commonly in use between the fourteenth to eighth centuries B.C.E. in Syria-Palestine.[10] The form of the letters here used supplies very important and interesting information regarding the history of the formation of the alphabet, as well as, incidentally, the arts of civilized life of those times in the land of Moab. This ancient monument, recording the heroic struggles of King Mesha with Omri and Ahab, was erected about 850 B.C.E. Here "we have the identical slab on which the workmen of the old world carved the history of their own times, and from which the eye of their contemporaries read thousands of years ago the record of events of which they themselves had been the witnesses."

In 1994, after examining both the Mesha Stele and the paper squeeze of it in the Louvre Museum, the French scholar André Lemaire reported that line 31 of the Mesha Stele bears the phrase "the house of David" (in Biblical Archaeology Review [May/June 1994], pp. 30-37).[11] Lemaire had to supply one destroyed letter, the first "D" in "[D]avid," to decode the wording. The complete sentence in the latter part of line 31 would then read, "As for Horonen, there lived in it the house of [D]avid," וחורננ. ישב. בה. בת[ד]וד. (Note: square brackets [ ] enclose letters or words that have been supplied where letters were destroyed or were on fragments that are still missing.) Most scholars find that no other letter supplied there yields a reading that makes sense. Baruch Margalit attempted to supply a different letter there: "m," along with several other letters in places after that. The reading that resulted was "Now Horoneyn was occupied at the en[d] of [my pre]decessor['s reign] by [Edom]ites."[12] However, Margalit's reading has failed to attract any significant support in scholarly publications.

In 2001, another French scholar, Pierre Bordreuil, reported (in an essay in French) that he and a few other scholars could not confirm Lemaire's reading of "the house of David" in line 31 of the stele.[13]

Whereas the later mention of the "House of David" on a Tel Dan stele fragment was written by an Aramaean enemy king, this inscription comes from a Moabite enemy of Israel, also boasting of a victory. If Lemaire is right, there are now two early references to David's dynasty, one in the Mesha Stele (mid-9th century) and the other in the Tel Dan Stele (mid-9th to mid-8th century).[14]Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

The identifications of the biblical Mesha, king of Moab, and of the biblical Omri, king of the northern kingdom of Israel, in the Mesha stele are generally accepted by the scholarly community, especially because what is said about them in the narrative of the Mesha stele agrees well with the narrative in the biblical books of Kings and Chronicles.

The identification of David in the Mesha stele, however, remains controversial. This controversy stems partly from the fragmentary state of line 31 of the Mesha stele and partly from a tendency since the 1990s, largely among European scholars, to question or dismiss the historical reliability of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). In Europe, P. R. Davies, Thomas L. Thompson, and Niels P. Lemche show a strong tendency to reject biblical historicity, whereas André Lemaire, K. A. Kitchen, Jens Bruun Kofoed, and other European scholars are exceptions to this tendency. Many scholars lean in one direction or the other but actually occupy the middle ground. In general, North American and Israeli scholars tend to be more willing to accept the identification of the biblical King David in the Mesha stele. The controversy over whether ancient inscriptions confirm the existence of the King David mentioned in the Bible usually focuses less on the Mesha stele and more on the Tel Dan stele.

The Stele is also significant in that it mentions the Hebrew name of God - YHWH. It is thought to be the earliest known reference to the sacred name in any artifact.

Text in Hebrew

The text, in Moabite, transcribed into modern Hebrew letters:

1. אנכ. משע. בנ. כמש.. . מלכ. מאב. הד 2. יבני | אבי. מלכ. על. מאב. שלשנ. שת. ואנכ. מלכ 3. תי. אחר. אבי | ואעש. הבמת. זאת. לכמש. בקרחה | ב[נס. י] 4. שע. כי. השעני. מכל. המלכנ. וכי. הראני. בכל. שנאי | עמר 5. י. מלכ. ישראל. ויענו. את. מאב. ימנ. רבן. כי. יאנפ. כמש. באר 6. צה | ויחלפה. בנה. ויאמר. גמ. הא. אענו. את. מאב | בימי. אמר. כ[...] 7. וארא. בה. ובבתה | וישראל. אבד. אבד. עלמ. וירש. עמרי. את א[ר] 8. צ. מהדבא | וישב. בה. ימה. וחצי. ימי. בנה. ארבענ. שת. ויש 9. בה. כמש. בימי | ואבנ. את. בעלמענ. ואעש. בה. האשוח. ואבנ 10. את. קריתנ | ואש. גד. ישב. בארצ. עטרת. מעלמ. ויבנ. לה. מלכ. י 11. שראל. את. עטרת | ואלתחמ. בקר. ואחזה | ואהרג. את. כל. העמ. [מ] 12. הקר. רית. לכמש. ולמאב | ואשב. משמ. את. אראל. דודה. ואס 13. חבה. לפני. כמש. בקרית | ואשב. בה. את. אש. שרנ. ואת. אש 14. מחרת | ויאמר. לי. כמש. לכ. אחז. את. נבה. על. ישראל | וא 15. הלכ. הללה. ואלתחמ. בה. מבקע. השחרת. עד. הצהרמ | ואח 16. זה. ואהרג. כלה. שבעת. אלפנ. גברנ. ו[גר]נ | וגברת. וגר 17. ת. ורחמת | כי. לעשתר. כמש. החרמתה | ואקח. משמ. א[ת. כ] 18. לי. יהוה. ואסחב. המ. לפני. כמש | ומלכ. ישראל. בנה. את 19. יהצ. וישב. בה. בהלתחמה. בי | ויגרשה. כמש. מפני | ו 20. אקח. ממאב. מאתנ. אש. כל. רשה | ואשאה. ביהצ. ואחזה. 21. לספת. על. דיבנ | אנכ. בנתי. קרחה. חמת. היערנ. וחמת 22. העפל | ואנכ. בנתי. שעריה. ואנכ. בנתי. מגדלתה | וא 23. נכ. בנתי. בת. מלכ. ואנכ. עשתי. כלאי. האש[וח למי]נ. בקרב 24. הקר | ובר. אנ. בקרב. הקר. בקרחה. ואמר. לכל. העמ. עשו. ל 25. כמ. אש. בר. בביתה | ואנכ. כרתי. המכרתת. לקרחה. באסר 26. [י]. ישראל | אנכ. בנתי. ערער. ואנכ. עשתי. המסלת. בארננ. 27. אנכ. בנתי. בת. במת. כי. הרס. הא | אנכ. בנתי. בצר. כי. עינ 28. ----- ש. דיבנ. חמשנ. כי. כל. דיבנ. משמעת | ואנכ. מלכ 29. ת[י] ----- מאת. בקרנ. אשר. יספתי. על. הארצ | ואנכ. בנת 30. [י. את. מה]דבא. ובת. דבלתנ | ובת. בעלמענ. ואשא. שמ. את. [...] 31. --------- צאנ. הארצ | וחורננ. ישב. בה. ב 32. --------- אמר. לי. כמש. רד. הלתחמ. בחורננ | וארד 33. ---------[ויש]בה. כמש. בימי. ועל[...]. משמ. עש 34. -------------- שת. שדק | וא

Translation

Note that in the original text some words start at the end of a line, but end at the beginning of the next. Where possible, this translation reflects this writing.

- I am Mesha, son of Kemosh[-yatti], the king of Moab, the Di-

- -bonite. My father ruled over Moab thirty years, and I rul-

- -ed after my father. And I made this high-place for Kemosh in Qarcho (or Qeriho, a sanctuary). [...]

- because he has saved me from all kings, and because he has shown me to all my enemies. Omr-

- -i was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemosh was angry with his la-

- -nd. And his son replaced him; and he said, "I will also oppress Moab." In my days he said so[...].

- But I looked down on him and on his house. And Israel has been defeated; has been defeated forever, And Omri took possession of the whole la-

- -nd of Madaba, and he lived there in his days and half the days of his son: forty years. And Kemosh restored

- it in my days. And I built Baal Meon, and I built a water reservoir in it. And I built

- Qiryaten. And the men of Gad lived in the land of Atarot from ancient times; and the king of Israel built

- Atarot for himself. and I fought against the city and captured it. And I killed all the people of

- the city as a sacrifice for Kemosh and for Moab. And I brought back the fire-hearth of his uncle from there; and I brou-

- -ght it before Kemosh in Qerioit, and I settled the men of Sharon there, as well as the men of

- Maharit. And Kemosh said to me, "Go, take Nebo from Israel." And I w-

- -ent in the night and fought against it from the daybreak until midday, and I t-

- -ook it and I killed it all: seven thousand men and (male) aliens, and women and (female) ali-

- -ens, and servant girls. Since for Ashtar Kemosh I banned it. And from there I took the ve-

- -ssels of Yahweh, and I brought them before Kemosh. And the king of Israel had built

- Jahaz, and he stayed there while he fought against me. And Kemosh drove him away from me. And

- I took from Moab two hundred men, all its division. And I led it up to Yahaz, And I took it

- in order to add it to Dibon. I have built Qarcho, the wall of the woods and the wall

- of the citadel. And I have built its gates; And I have built its towers. And

- I have built the house of the king; and I have made the double reservoir for the spring inside

- the city. And there was no cistern in the city of Qarcho, and I said to all the people, "Make

- yourselves a cistern at home." And I cut the moat for Qarcho by using prisoners of

- Israel. I have built Aroer, and I constructed the military road in Arnon.

- I have built Beth-Bamot, for it had been destroyed. I have built Bezer, for it lay in ruins.

- [...] men of Dibon stood in battle formation, for all Dibon were in subjection. And I rul-

- -ed [over the] hundreds in the towns which I have added to the land. And I

- have built Medeba and Beth-Diblaten and Beth-Baal-Meon, and I brought there ...

- ... flocks of the land. And Horonaim, there lived

- ... Kemosh said to me, "Go down, fight against Hauranen." And I went down

- ... and Kemosh restored it in my days . . .

- ...

See also

Template:ANE portal

- Tel Dan Stele

- Merneptah Stele

- David

Notes

- ↑ 1920 World Book, Volume VI, page 3867

- ↑ BibleGateway.com [1]

- ↑ BibleGateway.com[2]

- ↑ BibleGateway.com [3]

- ↑ Driver, Samuel. (1890), Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel, [4]

- ↑ BibleGateway.com [5]

- ↑ Driver, Samuel. (1890), Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel, [6]

- ↑ Davis, John. (1891), The Moabite Stone and the Hebrew Records; see also Christiananswers.net [7]

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ian Young (1993). Diversity in Pre-Exilic Hebrew, p. 38-39. ISBN 3161460588.

- ↑ "House of David" Restored in Moabite Inscription:A new restoration of a famous inscription reveals another mention of the "House of David" in the ninth century B.C.E.

- ↑ Baruch Margalit, "Studies in NWSemitic Inscriptions," Ugarit-Forschungen 26, p. 275

- ↑ Pierre Bordreuil, "A propos de l'inscription de Mesha': deux notes," in P. M. Michele Daviau, John W. Wevers and Michael Weigl [Eds.], The World of the Aramaeans III, pp. 158-167, especially pp. 162-163 [Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001]

- ↑ [[Time (magazine)|]], December 18, 1995.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Franz Praetorius (1905-6), "Zur Inschrift des Meša`," in: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 59, pp. 33-35; 60, p. 402.

- Dearman, J. Andrew (Ed.) (1989). Studies in the Mesha Inscription and Moab. Archaeology and Biblical Studies series, no. 2. Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press. ISBN 1-55540-357-3

- Davies, Philip R. (1992, 2nd edition 1995, reprinted 2004). In Search of 'Ancient Israel' Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Horn, Siegfried H., "The Discovery of the Moabite Stone," in The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth, Essays in Honor of David Noel Friedman in Celebration of His Sixtieth Birthday, (1983), Carol L. Meyers and M. O'Connor (eds.), pp. 488-505.

- Lemaire, André (1994). "'House of David' Restored in Moabite Inscription." Biblical Archaeology Review 20 (3) May/June, pp. 30-37.

- Margalit, Baruch ("1994"). "Studies in NWSemitic Inscriptions," Ugarit-Forschungen 26. Page 317 of this annual publication refers to "the recent publication (April, 1995) of two additional fragments" of another stele, therefore, the 1994 volume was actually published sometime after April 1995. On the Mesha stele inscription, see p. 275.

- Parker, Simon B. (1997). Stories in Scripture and Inscriptions: Comparative Studies on Narratives in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions and the Hebrew Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511620-8. See pp. 44-46 for a clear, perceptive outline of the contents of the inscription on the Mesha stele.

- Rainey, Anson F. (2001). "Mesha and Syntax." In J. Andrew Dearman and M. Patrick Graham (Eds.), The Land That I Will Show You, pp. 300-306. Supplement Series, no. 343. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 1-84127-257-4

- Mykytiuk, Lawrence J. (2004). Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200–539 B.C.E. Academia Biblica series, no. 12. Atlanta, Ga.: Society of Biblical Literature. See pp. 95-110 and 265-277. ISBN 1-58983-062-8

External links

- Biblical History The Jewish History Resource Center—Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Louvre collection — includes a large modern photo of the stele

- The Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901–6: "Moabite Stone," includes a translation of part of the inscription.

- Translation from Northwest Semitic Inscriptions

This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.