Mani

Mani (216-c. 274) was an Iranian religious prophet and preacher who founded Manichaeism, an ancient dualistic religion that was once prolific in Persia but is now extinct. Mani presented himself as a saviour figure and as an apostle of Jesus Christ. He is identified by a 4th century Manichaean Coptic papyri as the Paraclete-Holy Ghost- the forerunner of Jesus' second coming.

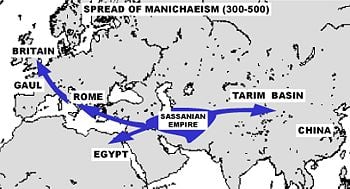

The teachings of Mani were once widely circulated in the ancient world, and their influence extended beyond Persia into the Roman Empire in the west, and India in the east. Neo-Manichaeism is a modern revivalist movement that is not directly connected to the ancient faith but is sympathetic to the teachings of Mani.

Biography

Until the late 20th century, the life and philosophy of Mani were pieced together largely from remarks by his detractors. In 1969, however, a Greek parchment codex of ca 400 C.E., was discovered in Upper Egypt, which is now designated Codex Manichaicus Coloniensis (because it is conserved at the University of Cologne). It combines a hagiographic account of Mani's career and spiritual development with information about Mani’s religious teachings and contains fragments of his Living (or Great) Gospel and his Letter to Edessa.

Mani was born in 216 C.E. of Iranian (Parthian) parentage in Babylon, Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), which was a part of Persian Empire about 210-276 C.E.. He was an exceptionally gifted child and he inherited his father's mystic temperament. He traveled far and wide to lands including Turkistan, India and Iran, among others, with many disciples to carry out evangelism. After forty years of travel he returned with his retinue to Persia and is said to have converted Peroz, King Shapur's brother to his teaching.

Mani, being influenced by Mandaeanism, began preaching at a young age. According to biographical accounts by al-Biruni, preserved in the 10th-century encyclopedia the Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadim, Mani received a revelation from a spirit during his youth, who allegedly taught him divine truths. During this period, the large existing religious groups, most notably Christianity and Zoroastrianism, were competing for stronger political and social power. Mani also followed the holy books Puran and Kural. Although having fewer adherents than Zoroastrianism, for example, Manichaeism won the support of high ranking political figures and with the aid of the Persian Empire, Mani would initiate several missionary excursions.

Mani's first excursion was to the Kushan Empire in northwestern India (several religious paintings in Bamiyan are attributed to him), where he is believed to have lived and taught for some time. He is related to have sailed to the Indus valley area of India in 240 or 241 C.E., and to have converted a Buddhist King, the Turan Shah of India. On that occasion, various Buddhist influences seem to have permeated Manichaeism: "Buddhist influences were significant in the formation of Mani's religious thought. The transmigration of souls became a Manichaean belief, and the quadripartite structure of the Manichaean community, divided between male and female monks (the "elect") and lay followers (the "hearers") who supported them, appears to be based on that of the Buddhist sangha".

After failing to win the favor of the next generation, and being disapproved of by the Zoroastrian clergy, Mani is reported to have died in prison awaiting execution by the Persian Emperor Bahram I, while alternate accounts have it that he was either flayed to death or beheaded.

Some historians claim he was of Persian parentage. Mani's father, Fatik or Pattig, was from Hamadan and his mother, Maryam, was of the family of the Kamsaragan, who claimed kinship with the Parthian royal house. Mani first encountered religion in his early youth while living with a Jewish ascetic group known as the Elkasites. In his mid-twenties, he came to believe that salvation is possible through education, self-denial, vegetarianism, fasting and chastity. He later claimed to be the Paraclete promised in the New Testament, the Last Prophet or Seal of the Prophets, finalizing a succession of men guided by God, which included figures such as Seth, Noah, Abraham, Shem, Nikotheos, Enoch, Zoroaster, Hermes, Plato, Buddha and Jesus. During his lifetime, Mani’s earliest missionaries were active in Mesopotamia, Persia, Palestine and Syria and in Egypt.

Growth of Manichaeism

It is theorized that the Manichees made every effort to include all known religious traditions. As a result they preserved many apocryphal Christian works, such as the Acts of Thomas, that would have been lost otherwise. Mani was eager to describe himself as a "disciple of Jesus Christ", but the orthodox church rejected him as a heretic.

Some fragments of a Manichaean book written in Turkish mention that in 803 C.E. the Khan of Uyghur Kingdom went to Turfan and sent three Manichaean Magistrates to pay respects to a senior Manichaean cleric in Mobei. The Manichaean manuscripts found in Turfan were written in three different Iranian scripts, viz. Middle Persian, Parthian and Sogdian script. These documents prove that Sogdia was a very important centre of Manichaeism during the early mediaeval period and it was perhaps the Sogdian merchants who brought the religion to Central Asia and China.

During the early 10th century, Uyghur emerged a very powerful empire under the influence of Buddhism with some Manichaean shrines converted into Buddhist temples. However, there was no denying the historical fact that the Uyghurs were worshippers of Mani. The Arabian historian An-Nadim informs us that the Uyghur Khan did his best to project Manichaeism in the Central Asian kingdom (of Saman). Chinese documents record that the Uyghur Manichaean clerics came to China to pay tribute to the imperial court in 934 C.E. The envoy of Song Dynasty by the name of Wang visited Manichaean temples in Gaochang. It appears that the popularity of Manichaeism slowly declined after 10th century in Central Asia.

Influence on Christianity

Some scholars find that the influence of Manichaeism subtly influences Christian thought, in the polarities of good and evil and in the increasingly vivid figure of Satan. This is partly through the influence of Augustine of Hippo, who converted to Christianity a short while after converting from Manichaeism, and whose writings continue to be enormously influential among Catholic theologians.

Interestingly, there are also parallels between Mani and Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. Mani claimed to be the successor to prophets like Jesus and other prophets whose teachings he said were locally corrupted (or corrupted by their followers). Mani declared himself, and was also referred to, as the Paraclete: a Biblical title, meaning "one who consoles" or "one who intercedes on our behalf", which the Orthodox tradition understood as referring to God in the person of the Holy Spirit. Mani claimed to be the last of the prophets, and also claimed that his prophethood was revealed to him by an angel. Muhammad, similarly, claimed to be the successor to prophets, notably the Hebrew prophets and Jesus. He claimed that the teachings of previous prophets were corrupted by their followers, e.g. Christians believing Jesus to be the son of God. He also claimed to be the last of God's prophets promised to humanity, as was said of Mani.

Mani was ranked #83 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

Writings

Although the original writings of the founding prophet Mani have been lost, significant portions remain preserved in Coptic manuscripts from Egypt and in later writings of fully-developed Manichaeism in China. Middle-Persian and Syriac are thought to have been Mani's native languages. He wrote seven holy books in Syriac (the main language spoken in the Near East before the Arab-Islamic conquest). fragments of his Living (or Great) Gospel and his Letter to Edessa.

(expand section)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Francis Legge, Forerunners and Rivals of Christianity, From 330 B.C.E. to 330 C.E. University Books New York, 1964.

- Maalouf, Amin . The Gardens of Light.

- Richard C. Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. ISBN 0-312-23338-8

External links

- MÂNI (CAIS)

- Mani & His Message (CAIS)

- Spirit Matter - Mani and Manichaeism (CAIS)

- Religious Syncretism: A Look at Manichaeism

- Manichaeist art - Washington University

- "Mani and Manichaeism in the J.R.Ritman Library"

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.