Luca Pacioli

Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (sometimes Paciolo) (1445–1514 or 1517) was an Italian mathematician and Franciscan friar, collaborator with Leonardo da Vinci, and seminal contributor to the field now known as accounting. He was also called Luca di Borgo after his birthplace, Borgo Santo Sepolcro, Tuscany.

Life

Early years

Luca Pacioli, sometimes called Lucas di Burgo, was born in Burgo San Sepolcro in Tuscany around 1450. .[1] He spent his early years in Venice, but after moving to Rome in 1464, came under the influence of the artist and mathematician Piero della Francesca and the architect Leon Battista Alberti. It is from these two important Renaissance figures that Pacioli received much of his early training, particularly in geometry, algebra, and painting and perspective. He remained in Rome until 1471, after which he taught in Perugia and traveled throughout Italy. [2]

Religious vocation

Pacioli became a Franciscan monk in 1487, and resumed teaching at Perugia until 1791.[3] In 1494, he published what is said to have been the first volumes in printed form on algebra and other mathematical subjects, an encyclopedic work called the Summa. He dedicated this work to his patron, Duke Guidobaldo, and in it, he praises his former teacher, Piero, whom he calls "our contemporary, and the prince of modern painting. [4]He was a traveling mathematics tutor until 1496, when he accepted an invitation from Lodovico Sforza ("Il Moro") to work in Milan. Lodovico appointed him to the chair of arithmetic and goemetry at the University of Pavia.

Friendship with Da Vinci

There he collaborated with, lived with, and taught mathematics to Leonardo da Vinci. He describes Da Vinci as "the excellent painter, architect and musician, a man gifted with all the virtues." <<<Müntz, Eugène. 1898. Leonardo da Vinci, artist, thinker and man of science. London: W. Heinemann. 219.>>> In 1497, Pacioli completed another work on geometric figures, the Divina Proportione, and convinced Da Vinci to supply the illustrations. <<<(Müntz 178). Da Vinci is said by Pacioli to have completed the Last Supper in 1498, while their friendship was in full force, and there may be reason to believe that Pacioli's influence may have shown itself in the painting's details. <<<Vasari, Giorgio, Mrs. Jonathan Foster, Edwin Howland Blashfield, Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield, and Albert A. Hopkins. 1897. Lives of seventy of the most eminent painters, sculptors and architects. London: G. Bell. 387.>>>Many commentators maintain that Da Vinci learned mathematics and science from Pacioli, who himself had studied under Piero. <<<Crowe, J. A., G. B. Cavalcaselle, R. Langton Douglas, S. Arthur Strong, G. de Nicola, and Tancred Borenius. 1903. A history of painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena, from the second to the sixteenth century. London: J. Murray.>>>The following year he participated in a scientific contest organized by his patron. <<<(Müntz 226)>>>During this period at Milan, Pacioli helped Da Vinci with the calculations for a huge statue of a horse, a model of which was made but later lost during later political conflicts. <<<Chisholm, Hugh. 1910. Leonardo Da Vinci. The encyclopædia britannica a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. New York: Encyclopædia Britannica. 448.>>>Pacioli himself states that the work was 26 feet tall, and would have weighed 200,000 pounds if it had been cast into bronze. <<<Masters in art a series of illustrated monographs. 1900. Boston: Bates and Guild Co.In December of 1499, Pacioli and Leonardo were forced to flee Milan when Louis XII of France seized the city and drove their patron out. After that, Pacioli and Leonardo frequently traveled together. In 1500 they first traveled to Mantua, then to Venice and, the spring time found the two in Florence, both seeking patrons and commissions. <<<McCurdy, Edward. 1904. Leonardo da Vinci. London: G. Bell and sons. 44-46.>>>

Later years

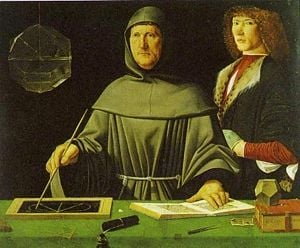

Pacioli removed to Pisa, where he taught from 1500 to 1505. In 1509 he was in Florence again, where he dedicated his Divina Proportione to Gonfaloniere Soderini. This work is believed to have been written much earlier. It in fact incorporates illustrations by Leonardo Da Vinci during the period when the artist and the monk were together in the Sforza's patronage. It is the third book, Libellus in Tres Partiales Tractatus Divisus Quinque Corporum Regularum, which was a translation of Pietro's Quinque Corporibus Regularibus into Italian. This introduced Piero's work to a wider audience, although it was incorporated into the Divina Proportione without attribution, leading to the charge that Pacioli stole the work and reproduced it as his own. <<<Cromwell, Peter R. 1997. Polyhedra. New York: Cambridge University Press. 124-125. ISBN 0521664055. Upon return to his hometown, Pacioli died of old age in 1517. Pacioli was a scholar of great stature, as is demonstrated by the fact that an excellent portrait of him was executed in 1495,in which he appears to be giving a geometry lesson to a young nobleman. (Cromwell 210).

Work

Pacioli published several works on mathematics, including:

- Summa de arithmetica, geometrica, proportioni et proportionalita (Venice 1494), a synthesis of the mathematical knowledge of his time, is also notable for including the first published description of the method of keeping accounts that Venetian merchants used during the Italian Renaissance, known as the double-entry accounting system. Although Pacioli codified rather than invented this system, he is widely regarded as the "Father of Accounting." The system he published included most of the accounting cycle as we know it today. He described the use of journals and ledgers, and warned that a person should not go to sleep at night until the debits equalled the credits! His ledger had accounts for assets (including receivables and inventories), liabilities, capital, income, and expenses—the account categories that are reported on an organization's balance sheet and income statement, respectively. He demonstrated year-end closing entries and proposed that a trial balance be used to prove a balanced ledger. Also, his treatise touches on a wide range of related topics from accounting ethics to cost accounting.

- De viribus quantitatis (Ms. Università degli Studi di Bologna, 1496–1508), a treatise on mathematics and magic. Written between 1496 and 1508 it contains the first ever reference to card tricks as well as guidance on how to juggle, eat fire and make coins dance. It is the first work to note that Da Vinci was left-handed. De viribus quantitatis is divided into three sections: mathematical problems, puzzles and tricks, and a collection of proverbs and verses. The book has been described as the "foundation of modern magic and numerical puzzles," but it was never published and sat in the archives of the University of Bologna, seen only by a small number of scholars since the Middle Ages. The book was rediscovered after David Singmaster, a mathematician, came across a reference to it in a 19th-century manuscript. An English translation was published for the first time in 2007.[2]

- Geometry (1509), a Latin work that follows Euclid closely.

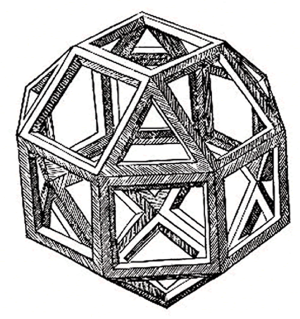

- De divina proportione (written in Milan in 1496–98, published in Venice in 1509). Two versions of the original manuscript are extant, one in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the other in the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire in Geneva. The subject was mathematical and artistic proportion, especially the mathematics of the golden ratio and its application in architecture. Leonardo da Vinci drew the illustrations of the regular solids in De divina proportione while he lived with and took mathematics lessons from Pacioli. Leonardo's drawings are probably the first illustrations of skeletonic solids, which allowed an easy distinction between front and back. The work also discusses the use of perspective by painters such as Piero della Francesca, Melozzo da Forlì, and Marco Palmezzano. As a side note, the "M" logo used by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is taken from De divina proportione.

Translation of Piero della Francesca's work

The third volume of Pacioli's De divina proportione was an Italian translation of Piero della Francesca's Latin writings On [the] Five Regular Solids, but it did not include an attribution to Piero. He was severely criticized for that by sixteenth-century art historian and biographer Giorgio Vasari. On the other hand, R. Emmett Taylor (1889–1956) said that Pacioli may have had nothing to do with that volume of translation, and that it may just have been appended to his work.

Legacy

Pacioli was one of the great compilers of his time, producing works that were summaries of the knowledge of his contemporaries. That he borrowed heavily from others to produce his works is not unprecedented among those who wish to bring the gems of knowledge to a wider audience, and certainly this was his aim.

Pacioli was a man of strong faith as well as of great knowledge. His entry into religious orders testifies to this as does the following excerpt from a passage meant to underscore the significance of the number three in religious life:

"There are three principle sins: Avarice, luxury and pride; three sorts of satisfaction for sin, fasting, almsgiving and prayer; three persons offended by sin, God, the sinner himself, and his neighbor; three witnesses in heaven, Pater, verbum, and spiritus sanctus; three degrees of penitence, contrition, confession and satisfaction..." <<<Sedgwick, W. T., H. W. Tyler, and Robert Payne Bigelow. 1939. A short history of science. New York: Macmillan Co. 233.>>>

While it is sometimes said that Pacioli offered nothing new to the sciences, his works stand as a monument to Renaissance publishing, being as they were a compendium of the significant intellectual accomplishments of his time. His life was enriched by the friendships he made with historic personages, and his writings attest to many facts that would otherwise have been lost to subsequent generations.

See also

- Franciscan

- Leonardo da Vinci

Notes

- ↑ Müntz, Eugène. 1898. Leonardo da Vinci, artist, thinker and man of science. London: W. Heinemann. 148.

- ↑ Crowe, J. A., G. B. Cavalcaselle, R. Langton Douglas, S. Arthur Strong, G. de Nicola, and Tancred Borenius. 1903. A history of painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena, from the second to the sixteenth century. London: J. Murray 35, 285.

- ↑ National Gallery (Great Britain). 1875. Descriptive and historical catalogue of the pictures in the National gallery with biographical notices of the painters. Foreign school. London: Her Maj. stationery office. 117.

- ↑ Dennistoun, James. 1851. Memoirs of the Dukes of Urbino, illustrating the arms, arts and literature of Italy. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. 2: 194-195.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Saporetti, Francesco. 1898. Fra Luca Paciolo; origine e sviluppo della partita doppia. Livorno: S. Belforte & Co.

- Bambach, Carmen. 2003. Leonardo, Left-Handed Draftsman and Writer. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Pacioli, Luca. 1509. De divina proportione (English: On the Divine Proportion), Luca Paganinem de Paganinus de Brescia (Antonio Capella). Venice

- Taylor, Emmet, R. No Royal Road: Luca Pacioli and his Times (1942)

External links

- Luca Pacioli: The Father of Accounting

- Full Biography of Pacioli (St.Andrews)

- The Enigma of Luca Pacioli's Portrait

- Outline of Pacioli's Treatise - PARTICULARIS DE COMPUTIS ET SCRIPTURIS1

- Lucas Pacioli - Catholic Encyclopedia article

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.