Philby, Kim

m (→In Moscow) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{epname|Philby, Kim}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}} | ||

{{Infobox Person | {{Infobox Person | ||

| name = Kim Philby | | name = Kim Philby | ||

| Line 41: | Line 43: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" | + | '''Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby''' (January 1, 1912 – May 11, 1988) was a high-ranking member of [[United Kingdom|British]] [[military intelligence|intelligence]] and also a spy for the [[Soviet Union]], serving as an [[NKVD]] and [[KGB]] operative and passed many crucial secrets to the Soviets in the early days of the [[Cold War]]. |

| − | + | Philby became a [[socialism|socialist]] and later a [[Marxism-Leninism|communist]] while attending the [[University of Cambridge]] in Cambridge, [[England]]. He was recruited into the Soviet intelligence apparatus after working for the [[Comintern]] in [[Vienna]] following graduation. He posed as a pro-[[fascism|fascist]] journalist and worked his way into British intelligence, where he came to serve as head of [[counter-espionage]] and other posts. This rise through the ranks enabled him to pass sensitive secrets to his Soviet handlers. Later, he was sent to Washington, where he coordinated British and American intelligence efforts, thus providing the Soviets with even more valuable information. | |

| + | |||

| + | In 1951, Philby's [[Washington, D.C.|Washington]] spy ring was nearly exposed, but he was able to warn his closest associates, [[Donald Duart Maclean|Donald Maclean]], and [[Guy Burgess]], who defected to the Soviet Union. Philby faced suspicion as the "third man" of the group, but after several years of investigation, he was publicly cleared of the charges and was re-posted to the [[Middle East]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | In 1963, Philby was revealed as a spy now known as the member of the [[Cambridge Five]], along with Maclean, Burgess, [[Anthony Blunt]], and [[John Cairncross]]. Philby is believed to have been the most successful of the five in providing classified information to the [[USSR]]. He evaded capture and fled to Russia, where he worked with Soviet intelligence but fell into a life of [[alcohol]]ic [[depression]]. Only after his death was he honored as a [[hero of the Soviet Union]]. | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| − | Born in [[Ambala]], [[Punjab (British India)|Punjab]], [[British Raj| | + | Born in [[Ambala]], [[Punjab (British India)|Punjab]], [[British Raj|India]], Philby was the son of [[Harry St. John Philby]], a British Army officer, [[diplomat]], explorer, [[author]], and [[Orientalist]] who converted to [[Islam]]<ref>''New York Times,'' [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9803EEDC133CF933A25754C0A962958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=6 Kim Philby and the Age of Paranoia.] Retrieved October 13, 2008.</ref> and was adviser to King [[Ibn Saud|Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia]]. Kim was [[nickname]]d after the [[protagonist]] in [[Rudyard Kipling]]'s novel, ''[[Kim (novel)|Kim]],'' about a young Irish-Indian boy who spies for the British in India during the nineteenth century. |

| − | After graduating from [[Westminster School]] in 1928 at the age of 16, Philby studied history and economics at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]] where | + | After graduating from [[Westminster School]] in 1928, at the age of 16, Philby studied [[history]] and [[economics]] at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], where became an admirer of [[Marxism]]. Philby reportedly asked one of his tutors, [[Maurice Dobb]], how he could serve the Communist movement, and Dobbs referred him to a Communist front organization in [[Paris]], known as the World Federation for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism. This was one of several fronts operated by the German [[Willi Münzenberg]], a leading Soviet agent in the [[Western world|West]]. Münzenberg in turn passed Philby to the [[Comintern]] underground in [[Vienna]], [[Austria]]. |

==Espionage activities== | ==Espionage activities== | ||

| − | The Soviet intelligence service | + | The Soviet intelligence service recruited Philby on the strength of his work for the Comintern. His case officers included [[Arnold Deutsch]] (codename OTTO), [[Theodore Maly]] (codename MAN), and [[Alexander Orlov]] (codename SWEDE). |

| − | In 1933, | + | In 1933, Philby was sent to Vienna to aid refugees who were fleeing [[Nazi Germany]]. However, in 1936, on orders from [[Moscow]], Philby began cultivating a pro-fascist persona, appearing at Anglo-German meetings, and editing a pro-[[Adolf Hitler|Hitler]] magazine. In 1937, he went to [[Spain]] as a freelance journalist and then as a correspondent for ''The Times'' of London—reporting on the war from a pro-[[Francisco Franco|Franco]] perspective. During this time, he engaged in various espionage duties for the Soviets, including writing spurious love letters interlaced with codewords. |

| − | Philby's right- | + | Philby's right-wing cover worked to perfection. In 1940, [[Guy Burgess]], a supposed British spy who was himself working for the Soviets, introduced him to British intelligence officer Marjorie Maxse, who in turn recruited Philby into the British intelligence service (SIS). Philby worked as an instructor in the arts of "[[black propaganda]]" and was later appointed to head SIS Section V, in charge of Spain, [[Portugal]], [[Gibraltar]], and [[Africa]]. There, he performed his duties well and came to the attention of British intelligence chief Sir [[Stewart Menzies]], better known as "C," who in 1944, appointed him to the key position as head of the new Section IX: Counter-espionage against the [[Soviet Union]]. As a deep-cover Soviet agent, Philby could hardly have positioned himself better. |

| − | Philby faced possible discovery in August | + | Philby faced possible discovery in August 1945, when [[Konstantin Volkov (diplomat)|Konstantin Volkov]], an officer of the [[NKVD]] (later [[KGB]]) informed SIS that he planned to defect to Britain with the promise that he would reveal the names of Soviet agents in SIS and the British Foreign Office. When the report reached Philby's desk, he tipped off Moscow, and the Russians were barely able to prevent Volkov's defection. |

===Postwar career=== | ===Postwar career=== | ||

| + | After the war, Philby was sent by SIS as Head of Station to [[Istanbul]] under the cover of First Secretary of the British Embassy. While there, he received a visit from fellow SIS officer and Soviet spy [[Guy Burgess]]. Philby is believed to have passed to Moscow information on the size of the [[United States]]' stockpile of atomic weapons and the U.S. capacity (at that time, severely limited) to produce new atomic bombs. Based in part on that information, Stalin went ahead with a 1948 [[Berlin Blockade|blockade of West Berlin]] and began a large-scale offensive armament of [[Kim Il Sung]]'s North Korean Army and Air Force, which would later culminate in the [[Korean War]]. | ||

| − | + | In January 1949, the British Government was informed that [[Venona project]] intercepts showed that nuclear secrets had been passed to the [[Soviet Union]] from the British Embassy in Washington in 1944 and 1945, by an agent code-named "Homer." Later in 1949, Philby was posted as First Secretary of the British Embassy in Washington, where he acted as liaison between British intelligence and the newly-formed [[CIA]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The two agencies launched an attempted revolution in Soviet-influenced [[Albania]], but Philby was apparently able to inform the Soviets of these plans. The exiled King [[Zog of Albania]] had offered troops and other volunteers to help, but for three years, every attempted landing in Albania met with a Soviet or Albanian Communist ambush. A similar attempt was blocked in [[Ukraine]], due to Philby's efforts. In addition, couriers who traveled to Soviet territory would often disappear, and British and American networks were producing no useful information. | |

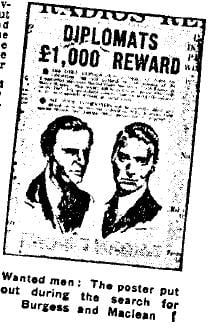

| − | + | [[Image:Burgess-maclean.JPG|thumb|British "wanted" poster for Philby's partners Burgess and McClean]] | |

| − | Philby was also able to tell Moscow just how much the CIA knew about its operations | + | After these disasters, the CIA and [[MI6]] largely gave up their attempts to plant agents in Soviet territory. Philby was also able to tell Moscow just how much the CIA knew about its operations and to suppress several reports that revealed the names of Soviet spies in the West. |

| − | In 1950, Philby was asked by the British to help track down the suspected traitor inside their Washington embassy. Knowing from the start that "Homer" was his old university friend | + | In 1950, Philby was asked by the British to help track down the suspected traitor inside their Washington embassy. Knowing from the start that "Homer" was his old university friend [[Donald MacLean]], Philby warned MacLean early in 1951. Meanwhile, Guy Burgess had been living in Philby's house, but he behaved recklessly and suspicion had fallen on him as well. |

| − | MacLean was identified in April 1951, and he defected to Moscow with Guy Burgess a month later in May 1951. Philby came under instant suspicion as the third man who had tipped them off. | + | MacLean was identified in April 1951, and he defected to Moscow with Guy Burgess a month later in May 1951. Philby came under instant suspicion as the third man who had tipped them off. |

===Cleared, caught, and defected=== | ===Cleared, caught, and defected=== | ||

| − | Philby resigned under a cloud | + | Philby resigned under a cloud. He was denied his pension and spent the next several years under investigation. He did not admit his true identity, however, and on October 25, 1955, against all expectations, he was cleared. Foreign Secretary [[Harold Macmillan]] made the public announcement exonerating Philby in the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]]: "While in government service he carried out his duties ably and conscientiously, and I have no reason to conclude that Mr. Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of his country, or to identify him with the so-called 'Third Man,' if indeed there was one." |

| − | Philby was then re-employed by MI6 as an "informant on retainer" agent, working under cover as a correspondent in Beirut for ''[[The Observer]]'' and ''[[The Economist]]''. | + | Philby was then re-employed by MI6 as an "informant on retainer" agent, working under cover as a correspondent in Beirut for ''[[The Observer]]'' and ''[[The Economist]]''. There, he was reportedly involved in [[Operation Musketeer (1956)|Operation Musketeer]], the British, French, and Israeli plan to attack [[Egypt]] and depose [[Gamal Abdel Nasser]]. |

| − | Suspicion again fell on Philby, however. There seemed to be a constant leak of information and it was alleged that | + | Suspicion again fell on Philby, however. There seemed to be a constant leak of information, and it was alleged that the Soviets had placed a high-level mole in British intelligence. Philby apparently became aware that the net was closing around him. In the last few months of 1962, he began to drink heavily and his behavior became increasingly erratic. Some believe that Philby was warned by Soviet spy handler [[Yuri Modin]], who served in the Soviet embassy in London, when he traveled to Beirut in December 1962. |

| − | + | Philby was soon confronted with new evidence on behalf of British intelligence by an old SIS friend, Nicholas Elliott. Before a second interview could take place, he defected to the Soviet Union in January 1963, departing Beirut on the Soviet freighter ''Dolmatova.'' Records later revealed that the ''Dolmatova'' left port so quickly its cargo remained scattered on the dock. | |

===In Moscow=== | ===In Moscow=== | ||

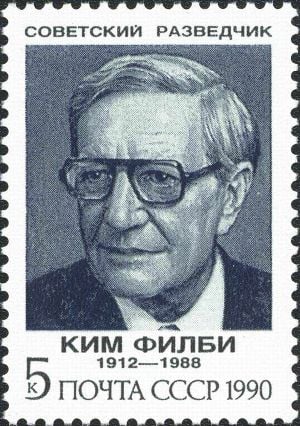

[[Image:1990 CPA 6266.jpg|thumb|right|Kim Philby on the 1990 [[USSR]] commemorative stamp]] | [[Image:1990 CPA 6266.jpg|thumb|right|Kim Philby on the 1990 [[USSR]] commemorative stamp]] | ||

| − | + | Philby soon surfaced in Moscow, and quickly discovered that he was not a colonel in the [[KGB]] as he thought, but still just agent TOM. It was 10 years before he walked through the doors of KGB headquarters. He suffered severe bouts of [[alcoholism]]. In Moscow, he seduced MacLean's American wife, Melinda, and abandoned his own wife, Eleanor, who left Russia in 1965.<ref>Eleanor Philby, 1968.</ref> According to information contained in the [[Mitrokhin Archive]], the head of KGB counterintelligence, [[Oleg Kalugin]] met Philby in 1972 and found him to be "a wreck of a man." | |

| − | Over the next few years Kalugin and his colleagues in the Foreign Intelligence Directorate rehabilitated Philby, using him to help devise active measures in the West and to run seminars for young agents about to be sent to [[Great Britain]], [[Australia]], or [[Ireland]]. In 1972 he | + | Over the next few years, Kalugin and his colleagues in the Foreign Intelligence Directorate rehabilitated Philby, using him to help devise active measures in the West and to run seminars for young agents about to be sent to [[Great Britain]], [[Australia]], or [[Ireland]]. In 1972, he married a Russian woman, [[Rufina Ivanova Pukhova]], who was 20 years his junior, with whom he lived until his death at age 76 in 1988. |

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | + | Kim Philby and his associates did severe damage to British and U.S. efforts in the early stages of the [[Cold War]]. He gave the Soviets information that they used to kill Western intelligence agents, withdraw their own agents who were in danger of exposure, and prevent defectors from coming to the West. He provided vital national security secrets regarding the state of the U.S. [[atomic weapons]] program, which encouraged [[Stalin]] to blockade [[Berlin]] and arm[[Kim Il Sung]] with weapons to launch the [[Korean War]]. The most highly-placed foreign spy ever known to penetrate the Western intelligence agencies, he was a master of deception, and one of the most effective spies in history. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Yet, he ended his life not as a hero of the Soviet Union for which he had sacrificed so much of his life and his integrity, but as a depressed [[alcoholism|alcoholic]] who was still very much an Englishman at heart. Only posthumously did he receive from the Soviets the public praise and appreciation which had escaped him in life. He was awarded a hero's funeral and numerous posthumous medals by the USSR. The Soviet Union itself collapsed in late 1991. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Philby in | + | ===Books=== |

| + | Philby's autobiography, ''My Silent War,'' was published in the West in 1968, as was his wife Eleanor's book, ''Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved''. Many other books and films have been based on his life: | ||

| + | *[[John le Carré]]'s novel (also a BBC television mini-series) ''[[Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy]]'' (1974) focuses on the hunt for a Soviet agent patterned after Philby. | ||

| + | *Graham Greene's novel, ''[[The Human Factor]]'' (1978), explores the moral themes of Philby's story, although Green claims none of the characters are based on Philby. | ||

| + | *In the Ted Allbeury novel, ''The Other Side of Silence'' (1981), Philby, near the end of his life, asks to return to Britain. | ||

| + | *The [[Frederick Forsyth]] novel, ''[[The Fourth Protocol]],'' features an elderly Kim Philby advising a Soviet leader on a plot to influence a British election in 1987. | ||

| + | *The [[Robert Littell (author)|Robert Littell]] novel, ''[[The Company (novel)|The Company]]'' (2002), features Philby as a confidant of former CIA Counter-Intelligence chief [[James Angleton]]. | ||

| + | *The novel, ''[[Fox at the Front]]'' (2003), by [[Douglas Niles]] and [[Michael Dobson (author)|Michael Dobson]] depicts a fictional Philby selling secrets to the Soviet Union during the alternate Battle of the Bulge. | ||

| − | === | + | ===Film and television=== |

| − | *The | + | * The character "Harry Lime" in the 1949 film, ''[[The Third Man]],'' has been said to be based on Kim Philby. A few years later, Philby was suspected of being the "third man" in the spy scandal. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* ''[[Cambridge Spies]],'' a 2003 four-part BBC drama, starring Toby Stephens as Kim Philby, Tom Hollander as Guy Burgess, Rupert Penry-Jones as Donald Maclean, and Samuel West as Anthony Blunt, which is told from Philby's point of view, recounts their lives and adventures from Cambridge days in the 1930s, through World War II, until the defection of Burgess and Maclean in 1951. | * ''[[Cambridge Spies]],'' a 2003 four-part BBC drama, starring Toby Stephens as Kim Philby, Tom Hollander as Guy Burgess, Rupert Penry-Jones as Donald Maclean, and Samuel West as Anthony Blunt, which is told from Philby's point of view, recounts their lives and adventures from Cambridge days in the 1930s, through World War II, until the defection of Burgess and Maclean in 1951. | ||

| − | * The 2005 film ''[[A Different Loyalty]]'' is an unattributed account taken from Eleanor Philby's book, | + | * The 2005 film, ''[[A Different Loyalty]],'' is an unattributed account taken from Eleanor Philby's book, ''Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved.'' The names of all characters, including the lead characters, have been changed. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * In the 2007 (TNT) television three-part series ''[[The Company (TV miniseries)|The Company]],'' Philby is portrayed by [[Tom Hollander]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * In the 2007 (TNT) television three-part series | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Borovik, Genrikh Aviėzerovich, and Phillip Knightley (ed.). ''The Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994. ISBN 9780316910156. |

| − | + | *Boyle, Andrew. ''The Fourth Man: The Definitive Account of Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, and Donald Maclean and Who Recruited Them to Spy for Russia''. New York: Dial Press, 1998. ASIN B000NPUZYI. | |

| − | + | *Hamrick, S. J. ''Deceiving the Deceivers: Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess''. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780300104165. | |

| − | + | *Knightley, Phillip. ''The Master Spy: The Story of Kim Philby''. New York: Knopf, 1989. ISBN 0233000488. | |

| − | * | + | *Philby, Eleanor. ''Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved''. London: H. Hamilton, 1968. ISBN 9780241015698. |

| − | + | *Philby, Kim. ''My Silent War''. London: Grafton, 1989. ISBN 0586028609. | |

| − | + | *Seale, Patrick, and Maureen McConville. ''Philby: The Long Road to Moscow''. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973. ISBN 9780241023679. | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:biography]] | [[Category:biography]] | ||

[[Category:politics]] | [[Category:politics]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history]] | ||

{{credit|227417132}} | {{credit|227417132}} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:31, 17 April 2018

| Kim Philby | |

Old photo from the FBI's records

| |

| Born | Harold Adrian Russell Philby January 01 1912 Ambala, Punjab, British India |

|---|---|

| Died | May 11 1988 (aged 76) Moscow, USSR |

| Spouse(s) | Alice (Litzi) Friedman Aileen Furse Eleanor Brewer Rufina Ivanova |

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (January 1, 1912 – May 11, 1988) was a high-ranking member of British intelligence and also a spy for the Soviet Union, serving as an NKVD and KGB operative and passed many crucial secrets to the Soviets in the early days of the Cold War.

Philby became a socialist and later a communist while attending the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. He was recruited into the Soviet intelligence apparatus after working for the Comintern in Vienna following graduation. He posed as a pro-fascist journalist and worked his way into British intelligence, where he came to serve as head of counter-espionage and other posts. This rise through the ranks enabled him to pass sensitive secrets to his Soviet handlers. Later, he was sent to Washington, where he coordinated British and American intelligence efforts, thus providing the Soviets with even more valuable information.

In 1951, Philby's Washington spy ring was nearly exposed, but he was able to warn his closest associates, Donald Maclean, and Guy Burgess, who defected to the Soviet Union. Philby faced suspicion as the "third man" of the group, but after several years of investigation, he was publicly cleared of the charges and was re-posted to the Middle East.

In 1963, Philby was revealed as a spy now known as the member of the Cambridge Five, along with Maclean, Burgess, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross. Philby is believed to have been the most successful of the five in providing classified information to the USSR. He evaded capture and fled to Russia, where he worked with Soviet intelligence but fell into a life of alcoholic depression. Only after his death was he honored as a hero of the Soviet Union.

Early life

Born in Ambala, Punjab, India, Philby was the son of Harry St. John Philby, a British Army officer, diplomat, explorer, author, and Orientalist who converted to Islam[1] and was adviser to King Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia. Kim was nicknamed after the protagonist in Rudyard Kipling's novel, Kim, about a young Irish-Indian boy who spies for the British in India during the nineteenth century.

After graduating from Westminster School in 1928, at the age of 16, Philby studied history and economics at Trinity College, Cambridge, where became an admirer of Marxism. Philby reportedly asked one of his tutors, Maurice Dobb, how he could serve the Communist movement, and Dobbs referred him to a Communist front organization in Paris, known as the World Federation for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism. This was one of several fronts operated by the German Willi Münzenberg, a leading Soviet agent in the West. Münzenberg in turn passed Philby to the Comintern underground in Vienna, Austria.

Espionage activities

The Soviet intelligence service recruited Philby on the strength of his work for the Comintern. His case officers included Arnold Deutsch (codename OTTO), Theodore Maly (codename MAN), and Alexander Orlov (codename SWEDE).

In 1933, Philby was sent to Vienna to aid refugees who were fleeing Nazi Germany. However, in 1936, on orders from Moscow, Philby began cultivating a pro-fascist persona, appearing at Anglo-German meetings, and editing a pro-Hitler magazine. In 1937, he went to Spain as a freelance journalist and then as a correspondent for The Times of London—reporting on the war from a pro-Franco perspective. During this time, he engaged in various espionage duties for the Soviets, including writing spurious love letters interlaced with codewords.

Philby's right-wing cover worked to perfection. In 1940, Guy Burgess, a supposed British spy who was himself working for the Soviets, introduced him to British intelligence officer Marjorie Maxse, who in turn recruited Philby into the British intelligence service (SIS). Philby worked as an instructor in the arts of "black propaganda" and was later appointed to head SIS Section V, in charge of Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar, and Africa. There, he performed his duties well and came to the attention of British intelligence chief Sir Stewart Menzies, better known as "C," who in 1944, appointed him to the key position as head of the new Section IX: Counter-espionage against the Soviet Union. As a deep-cover Soviet agent, Philby could hardly have positioned himself better.

Philby faced possible discovery in August 1945, when Konstantin Volkov, an officer of the NKVD (later KGB) informed SIS that he planned to defect to Britain with the promise that he would reveal the names of Soviet agents in SIS and the British Foreign Office. When the report reached Philby's desk, he tipped off Moscow, and the Russians were barely able to prevent Volkov's defection.

Postwar career

After the war, Philby was sent by SIS as Head of Station to Istanbul under the cover of First Secretary of the British Embassy. While there, he received a visit from fellow SIS officer and Soviet spy Guy Burgess. Philby is believed to have passed to Moscow information on the size of the United States' stockpile of atomic weapons and the U.S. capacity (at that time, severely limited) to produce new atomic bombs. Based in part on that information, Stalin went ahead with a 1948 blockade of West Berlin and began a large-scale offensive armament of Kim Il Sung's North Korean Army and Air Force, which would later culminate in the Korean War.

In January 1949, the British Government was informed that Venona project intercepts showed that nuclear secrets had been passed to the Soviet Union from the British Embassy in Washington in 1944 and 1945, by an agent code-named "Homer." Later in 1949, Philby was posted as First Secretary of the British Embassy in Washington, where he acted as liaison between British intelligence and the newly-formed CIA.

The two agencies launched an attempted revolution in Soviet-influenced Albania, but Philby was apparently able to inform the Soviets of these plans. The exiled King Zog of Albania had offered troops and other volunteers to help, but for three years, every attempted landing in Albania met with a Soviet or Albanian Communist ambush. A similar attempt was blocked in Ukraine, due to Philby's efforts. In addition, couriers who traveled to Soviet territory would often disappear, and British and American networks were producing no useful information.

After these disasters, the CIA and MI6 largely gave up their attempts to plant agents in Soviet territory. Philby was also able to tell Moscow just how much the CIA knew about its operations and to suppress several reports that revealed the names of Soviet spies in the West.

In 1950, Philby was asked by the British to help track down the suspected traitor inside their Washington embassy. Knowing from the start that "Homer" was his old university friend Donald MacLean, Philby warned MacLean early in 1951. Meanwhile, Guy Burgess had been living in Philby's house, but he behaved recklessly and suspicion had fallen on him as well.

MacLean was identified in April 1951, and he defected to Moscow with Guy Burgess a month later in May 1951. Philby came under instant suspicion as the third man who had tipped them off.

Cleared, caught, and defected

Philby resigned under a cloud. He was denied his pension and spent the next several years under investigation. He did not admit his true identity, however, and on October 25, 1955, against all expectations, he was cleared. Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan made the public announcement exonerating Philby in the House of Commons: "While in government service he carried out his duties ably and conscientiously, and I have no reason to conclude that Mr. Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of his country, or to identify him with the so-called 'Third Man,' if indeed there was one."

Philby was then re-employed by MI6 as an "informant on retainer" agent, working under cover as a correspondent in Beirut for The Observer and The Economist. There, he was reportedly involved in Operation Musketeer, the British, French, and Israeli plan to attack Egypt and depose Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Suspicion again fell on Philby, however. There seemed to be a constant leak of information, and it was alleged that the Soviets had placed a high-level mole in British intelligence. Philby apparently became aware that the net was closing around him. In the last few months of 1962, he began to drink heavily and his behavior became increasingly erratic. Some believe that Philby was warned by Soviet spy handler Yuri Modin, who served in the Soviet embassy in London, when he traveled to Beirut in December 1962.

Philby was soon confronted with new evidence on behalf of British intelligence by an old SIS friend, Nicholas Elliott. Before a second interview could take place, he defected to the Soviet Union in January 1963, departing Beirut on the Soviet freighter Dolmatova. Records later revealed that the Dolmatova left port so quickly its cargo remained scattered on the dock.

In Moscow

Philby soon surfaced in Moscow, and quickly discovered that he was not a colonel in the KGB as he thought, but still just agent TOM. It was 10 years before he walked through the doors of KGB headquarters. He suffered severe bouts of alcoholism. In Moscow, he seduced MacLean's American wife, Melinda, and abandoned his own wife, Eleanor, who left Russia in 1965.[2] According to information contained in the Mitrokhin Archive, the head of KGB counterintelligence, Oleg Kalugin met Philby in 1972 and found him to be "a wreck of a man."

Over the next few years, Kalugin and his colleagues in the Foreign Intelligence Directorate rehabilitated Philby, using him to help devise active measures in the West and to run seminars for young agents about to be sent to Great Britain, Australia, or Ireland. In 1972, he married a Russian woman, Rufina Ivanova Pukhova, who was 20 years his junior, with whom he lived until his death at age 76 in 1988.

Legacy

Kim Philby and his associates did severe damage to British and U.S. efforts in the early stages of the Cold War. He gave the Soviets information that they used to kill Western intelligence agents, withdraw their own agents who were in danger of exposure, and prevent defectors from coming to the West. He provided vital national security secrets regarding the state of the U.S. atomic weapons program, which encouraged Stalin to blockade Berlin and armKim Il Sung with weapons to launch the Korean War. The most highly-placed foreign spy ever known to penetrate the Western intelligence agencies, he was a master of deception, and one of the most effective spies in history.

Yet, he ended his life not as a hero of the Soviet Union for which he had sacrificed so much of his life and his integrity, but as a depressed alcoholic who was still very much an Englishman at heart. Only posthumously did he receive from the Soviets the public praise and appreciation which had escaped him in life. He was awarded a hero's funeral and numerous posthumous medals by the USSR. The Soviet Union itself collapsed in late 1991.

Books

Philby's autobiography, My Silent War, was published in the West in 1968, as was his wife Eleanor's book, Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved. Many other books and films have been based on his life:

- John le Carré's novel (also a BBC television mini-series) Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974) focuses on the hunt for a Soviet agent patterned after Philby.

- Graham Greene's novel, The Human Factor (1978), explores the moral themes of Philby's story, although Green claims none of the characters are based on Philby.

- In the Ted Allbeury novel, The Other Side of Silence (1981), Philby, near the end of his life, asks to return to Britain.

- The Frederick Forsyth novel, The Fourth Protocol, features an elderly Kim Philby advising a Soviet leader on a plot to influence a British election in 1987.

- The Robert Littell novel, The Company (2002), features Philby as a confidant of former CIA Counter-Intelligence chief James Angleton.

- The novel, Fox at the Front (2003), by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson depicts a fictional Philby selling secrets to the Soviet Union during the alternate Battle of the Bulge.

Film and television

- The character "Harry Lime" in the 1949 film, The Third Man, has been said to be based on Kim Philby. A few years later, Philby was suspected of being the "third man" in the spy scandal.

- Cambridge Spies, a 2003 four-part BBC drama, starring Toby Stephens as Kim Philby, Tom Hollander as Guy Burgess, Rupert Penry-Jones as Donald Maclean, and Samuel West as Anthony Blunt, which is told from Philby's point of view, recounts their lives and adventures from Cambridge days in the 1930s, through World War II, until the defection of Burgess and Maclean in 1951.

- The 2005 film, A Different Loyalty, is an unattributed account taken from Eleanor Philby's book, Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved. The names of all characters, including the lead characters, have been changed.

- In the 2007 (TNT) television three-part series The Company, Philby is portrayed by Tom Hollander.

Notes

- ↑ New York Times, Kim Philby and the Age of Paranoia. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Eleanor Philby, 1968.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Borovik, Genrikh Aviėzerovich, and Phillip Knightley (ed.). The Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994. ISBN 9780316910156.

- Boyle, Andrew. The Fourth Man: The Definitive Account of Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, and Donald Maclean and Who Recruited Them to Spy for Russia. New York: Dial Press, 1998. ASIN B000NPUZYI.

- Hamrick, S. J. Deceiving the Deceivers: Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780300104165.

- Knightley, Phillip. The Master Spy: The Story of Kim Philby. New York: Knopf, 1989. ISBN 0233000488.

- Philby, Eleanor. Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved. London: H. Hamilton, 1968. ISBN 9780241015698.

- Philby, Kim. My Silent War. London: Grafton, 1989. ISBN 0586028609.

- Seale, Patrick, and Maureen McConville. Philby: The Long Road to Moscow. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973. ISBN 9780241023679.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.