Jesus Prayer

The Jesus Prayer, also called the Prayer of the Heart, is a short, formulaic prayer this is widely used in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Its practice is an integral part of the eremitic tradition of prayer known as Hesychasm (Greek: ἡσυχάζω, hesychazo, "to keep stillness"), the subject of the Philokalia (Greek: φιλοκαλείν, "love of beauty"), a collection of 4th to 15th century texts on prayer, compiled in the late 18th century by St. Nicodemus the Hagiorite and St. Makarios of Corinth. The monastic state of Mount Athos is a centre of the practice of the Jesus Prayer. The most common form of the prayer involves repetition of the phrase, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner."

While its tradition, on historical grounds, also belongs to the Eastern Catholics, and there have been a number of Roman Catholic texts on the Jesus Prayer, its practice has never achieved the same popularity in the Western Church as in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Moreover, the Eastern Orthodox theology of the Jesus Prayer enunciated in the 14th century by St. Gregory Palamas has never been fully accepted by the Roman Catholic Church.[1]

Origins

The prayer's origin is most likely the Egyptian desert, which was settled by the monastic Desert Fathers in the fifth century.[2]

The practice of repeating the prayer continually dates back to at least the fifth century. The earliest known mention is in On Spiritual Knowledge and Discrimination of St. Diadochos of Photiki (400-ca. 486), a work found in the first volume of the Philokalia. The Jesus Prayer is described in Diadochos's work in terms very similar} to St. John Cassian's (ca. 360-435) description in the Conferences 9 and 10 of the repetitive use of a passage of the Psalms. St. Diadochos ties the practice of the Jesus Prayer to the purification of the soul and teaches that repetition of the prayer produces inner peace.

The use of the Jesus Prayer is recommended in the Ladder of Divine Ascent of St. John Climacus (ca. 523–606) and in the work of St. Hesychios the Priest (ca. 8th century), Pros Theodoulon, found in the first volume of the Philokalia. The use of the Jesus Prayer according to the tradition of the Philokalia is the subject of the 19th century anonymous Russian spiritual classic The Way of a Pilgrim.

Though the Jesus Prayer has been practiced through the centuries as part of the Eastern tradition, in the 20th century it also began to be used in some Western churches, including some Roman Catholic and Anglican churches.

Theology

The Jesus Prayer is composed of two statements. The first one is a statement of faith, acknowledging the divine nature of Christ. The second one is the acknowledgment of ones own sinfulness. Out of them the petition itself emerges: "have mercy."

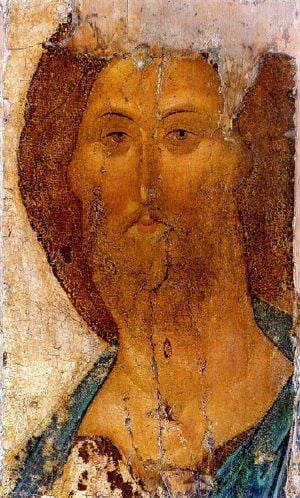

The hesychastic practice of the Jesus Prayer is founded on the biblical view by which God's name is conceived as the place of his presence. The Eastern Orthodox mysticism has no images or representations. The mystical practice (the prayer and the meditation) doesn't lead to perceiving representations of God (see below Palamism). Thus, the most important means of a life consecrated to praying is the invoked name of God, as it is emphasized since the 5th century by the Thebai] anchorites, or by the later Athonite hesychasts. For the Eastern Orthodox the power of the Jesus Prayer comes not from its content, but from the very invocation of the Jesus' name.

Scriptural roots

The Eastern Orthodox Church acknowledges two sources of the divine revelation: the Bible and the Holy Tradition. The Church doesn't allow laymen to preach or to interpret to the others the Bible (seen as being inspired by the Holy SpiriHoly Ghost) because of its deepness and richness in meanings, and of the perils of heresy. The described three levels of its text (literal/historical, allegorical/metaphorical and anagogical/mystical) are fitted to various levels of the personal spiritual development of the reader. On the other part, the Holy Tradition, equally seen as the word of God, is composed of the oral teachings of the Church, part of them embodied in writings throughout the history (like the canon laws and the dogmatic definitions of the general and local synods, the writings of the [[Holy Fathers, or the liturgical books). It isn't, for the Eastern Orthodox, something that changes or develops with time, but a sum of doctrines strongly linked to the Scriptures, held by the Church continuously since the Apostolic times.

Theologically, the Jesus Prayer is considered to be the response of the Holy Tradition to the lesson taught by the parable of the Publican and the Pharisee, in which the Pharisee demonstrates the improper way to pray by exclaiming: "Thank you Lord that I am not like the Publican," whereas the Publican prays correctly in humility, saying "Lord have mercy on me, the sinner" (Luke 18:10-14).[3]

Palamism, the underlying theology

The Essence-Energies distinction, a central principle in the Eastern Orthodox theology, was formulated by St. Gregory Palamas in the 14th century in support of the mystical practices of Hesychasm and against Barlaam of Seminara. It stands that God's essence (Greek: Οὐσία, ousia) is distinct from God's energies, or manifestations in the world, by which men can experience the Divine. The energies are "unbegotten" or "uncreated." They were revealed in various episodes of the Bible: the burning bush seen by Moses, the Light on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration.

Apophatism[4] (negative theology) is the main characteristic of the Eastern theological tradition. Incognoscibility isn't conceived as agnosticism or refusal to know God, because the Eastern theology isn't concerned with abstract concepts; it is contemplative, with a discourse on things above rational understanding. Therefore dogmas are often expressed antinomically.

For the Eastern Orthodox the knowledge of the uncreated energies is usually linked to apophatism.

Repentance in Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds a non-juridical view of sin, by contrast to the satisfaction view of atonement for sin as articulated in the West, firstly by Anselm of Canterbury (as debt of honor) and Thomas Aquinas (as a moral debt). The terms used in the East are less legalistic (grace, punishment), and more medical (sickness, healing) with less exacting precision. Sin, therefore, does not carry with it the guilt for breaking a rule, but rather the impetus to become something more than what men usually are. One repents not because one is or isn't virtuous, but because human nature can change. Repentance (Greek: μετάνοια, metanoia, "changing one's mind") isn't remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one's freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man's original state).[5] This is reflected in the Mystery of Confession for which, not being limited to a mere confession of sins and presupposing recommendations or penalties, it is primarily that the priest acts in his capacity of spiritual father.[6] The Mystery of Confession is linked to the spiritual development of the individual, and relates to the practice of choosing an elder to trust as his or her spiritual guide, turning to him for advice on the personal spiritual development, confessing sins, and asking advice.

As stated at the local Council of Constantinople in 1157, Christ brought his redemptive sacrifice not to the Father alone, but to the Trinity as a whole. In the Eastern Orthodox theology redemption isn't seen as ransom. It is the reconciliation of God with man, the manifestation of God’s love for humanity. Thus, it is not the anger of God the Father but His love that lies behind the sacrificial death of his son on the cross.[6]

The redemption of man is not considered to have taken place only in the past, but continues to this day through theosis. The initiative belongs to God, but presupposes man's active acceptance (not an action only, but an attitude), which is a way of perpetually receiving God.[5]

Distinctiveness from analogues in other religions

The practice of contemplative or meditative chanting is known from several religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam (e.g. japa, zikr). The form of internal contemplation involving profound inner transformations affecting all the levels of the self is common to the traditions that posit the ontological value of personhood.[7] The history of these practices, including their possible spread from one religion to another, is not well understood. Such parallels (like between unusual psycho-spiritual experiences, breathing practices, postures, spiritual guidances of elders, peril warnings) might easily have arisen independently of one another, and in any case must be considered within their particular religious frameworks.

Although some aspects of the Jesus Prayer may resemble some aspects of other traditions, its Christian character is central rather than mere "local color." The aim of the Christian practicing it is not humility, love, or purification of sinful thoughts, but becoming holy and seeking union with God (theosis), which subsumes them. Thus, for the Eastern Orthodox:

- The Jesus Prayer is, first of all, a prayer addressed to God. It's not a means of self-deifying or self-deliverance, but a counterexample to Adam's pride, repairing the breach it produced between man and God.

- The aim is not to be dissolved or absorbed into nothingness or into God, or reach another state of mind, but to (re)unite[8] with God (which by itself is a process) while remaining a distinct person.

- It is an invocation of Jesus' name, because Christian anthropology and soteriology are strongly linked to Christology in Orthodox monasticism.

- In a modern context the continuing repetition is regarded by some as a form of meditation, the prayer functioning as a kind of mantra. However, Orthodox users of the Jesus Prayer emphasize the invocation of the name of Jesus Christ that St Hesychios describes in Pros Theodoulon which would be contemplation on the Triune God rather than simply emptying the mind.

- Acknowledging "a sinner" is to lead firstly to a state of humbleness and repentance, recognizing one's own sinfulness.

- Practicing the Jesus Prayer is strongly linked to mastering passions of both soul and body, e.g. by fasting. For the Eastern Orthodox not the body is wicked, but "the bodily way of thinking" is; therefore salvation also regards the body.

- Unlike mantras, the Jesus Prayer may be translated into whatever language the pray-er customarily uses. The emphasis is on the meaning not on the mere utterance of certain sounds.

- There is no emphasis on the psychosomatic techniques, which are merely seen as helpers for uniting the mind with the heart, not as prerequisites.

A magistral way of meeting God for the Eastern Orthodox, the Jesus Prayer does not harbor any secrets in itself, nor does its practice reveal any esoteric truths. Instead, as a hesychastic practice, it demands setting the mind apart from rational activities and ignoring the physical senses for the experiential knowledge of God. It stands along with the regular expected actions of the believer (prayer, almsgiving, repentance, fasting etc.) as the response of the Orthodox Tradition to St. Paul's challenge to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess 5:17).[3]

Practice

"There isn't Christian Mysticism without Theology, especially there isn't Theology without Mysticism," writes Vladimir Lossky, for outside the Church the personal experience would have no certainty and objectivity, and "Church teachings would have no influence on souls without expressing a somehow inner experience of the truth it offers." For the Eastern Orthodox the aim isn't knowledge itself; theology is, finally, always a means serving a goal above any knowledge: theosis.

The individual experience of the Eastern Orthodox mystic most often remains unknown. With very few exceptions, there aren't autobiographical writings on the inner life in the East. The mystical union pathway remains hidden, being unveiled only to the confessor or to the apprentices. "The mystical individualism has remain unknown to the spiritual life of the Eastern Church," remarks Lossky.

The practice of the Jesus Prayer is integrated into the mental ascesis undertaken by the Orthodox monastic in the practice of hesychasm.

In the Eastern tradition the prayer is said or prayed repeatedly, often with the aid of a prayer rope (Russian: chotki; Greek: komvoskini), which is a cord, usually woolen, tied with many knots. The person saying the prayer says one repetition for each knot. It may be accompanied by prostrations and the sign of the cross, signaled by beads strung along the prayer rope at intervals.

Psychosomatic techniques

There aren't fixed, invariable rules for those who pray, "the way there is no mechanical, physical or mental technique which can force God to show his presence" (Metropolitan Kallistos Ware).[9]

People who say the prayer as part of meditation often synchronize it with their breathing; breathing in while calling out to God and breathing out while praying for mercy.

Monks often pray this prayer many hundreds of times each night as part of their private cell vigil ("cell rule"). Under the guidance of an Elder (Russian Starets; Greek Gerondas), the monk aims to internalize the prayer, so that he is praying unceasingly. St. Diadochos of Photiki refers in On Spiritual Knowledge and Discrimination to the automatic repetition of the Jesus Prayer, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, even in sleep. This state is regarded as the accomplishment of Saint Paul's exhortation to the Thessalonians to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thessalonians 5:17).

Levels of the prayer

Paul Evdokimov, a 20th century Russian philosopher and theologian, writes about beginner's way of praying: initially, the prayer is excited because the man is emotive and a flow of psychic contents is expressed. In his view this condition comes, for the modern men, from the separation of the mind from the heart: "The prattle spreads the soul, while the silence is drawing it together." Old fathers condemned elaborate phraseologies, for one word was enough for the publican, and one word saved the thief on the cross. They only uttered Jesus' name by which they were contemplating God. For Evdokimov the acting faith denies any formalism which quickly installs in the external prayer or in the life duties; he quotes St. Seraphim: "The prayer is not thorough if the man is self-conscious and he is aware he's praying."

"Because the prayer is a living reality, a deeply personal encounter with the living God, it is not to be confined to any given classification or rigid analysis"[3] an on-line catechism reads. As general guidelines for the practitioner, different number of levels (3, 7 or 9) in the practice of the prayer are distinguished by Orthodox fathers. They are to be seen as being purely informative, because the practice of the Prayer of the Heart is learned under personal spiritual guidance in Eastern Orthodoxy which emphasizes the perils of temptations when it's done by one's own. Thus, Theophan the Recluse, a 19th century Russian spiritual writer, talks about three stages:[3]

- The oral prayer (the prayer of the lips) is a simple recitation, still external to the practitioner.

- The focused prayer, when "the mind is focused upon the words" of the prayer, "speaking them as if they were our own."

- The prayer of the heart itself, when the prayer is no longer something we do but who we are.

Others, like Father Archimandrite Ilie Cleopa, one of the most representative spiritual fathers of contemporary Romanian Orthodox monastic spirituality, talk about nine levels. They are the same path to theosis, more slenderly differentiated:

- The prayer of the lips.

- The prayer of the mouth.

- The prayer of the tongue.

- The prayer of the voice.

- The prayer of the mind.

- The prayer of the heart.

- The active prayer.

- The all-seeing prayer.

- The contemplative prayer.

In its more advanced use, the monk aims to attain to a sober practice of the Jesus Prayer in the heart free of images. It is from this condition, called by Saints John Climacus and Hesychios the "guard of the mind," that the monk is raised by the Divine grace to contemplation.

Variants of repetitive formulas

A number of different repetitive prayer formulas have been attested in the history of Eastern Orthodox monasticism: the Prayer of St. Ioannikios the Great (754–846): "My hope is the Father, my refuge is the Son, my shelter is the Holy Ghost, O Holy Trinity, Glory to You," the repetitive use of which is described in his Life; or the more recent practiceTemplate:Huh of St. Nikolaj Velimirović.

Similarly to the flexibility of the practice of the Jesus Prayer, there is no imposed standardization of its form. The prayer can be from as short as "Have mercy on me" ("Have mercy on us"), or even "Jesus," to its longer most common form. It can also contain a call to the Theotokos (Virgin Mary), or to the saints. The single essential and invariable element is Jesus' name.[9]

- Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. (a very common form)

- Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me. (common variant in Orthodox Christianity as on Mount Athos)

- Lord have mercy.

- Jesus have mercy. (not an Orthodox formula)

- Christ have mercy. (not an Orthodox formula)

Notes

- ↑ Pope John Paul II's Angelus Message, 1996-08-11.

- ↑ Antoine Guillaumont reports the finding of an inscription containing the Jesus Prayer in the ruins of a cell in the Egyptian desert dated roughly to the period being discussed - Antoine Guillaumont, Une inscription copte sur la prière de Jesus in Aux origines du monachisme chrétien, Pour une phénoménologie du monachisme, pp. 168–83. In Spiritualité orientale et vie monastique, No 30. Bégrolles en Mauges (Maine & Loire), France: Abbaye de Bellefontaine.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Fr. Steven Peter Tsichlis, The Jesus Prayer, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America,Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ Eastern Orthodox theology doesn't stand Thomas Aquinas' interpretation to the Mystycal theology of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (modo sublimiori and modo significandi, by which Aquinas unites positive and negative theologies, transforming the negative one into a correction of the positive one). Like pseudo-Denys, the Eastern Church remarks the antinomy between the two ways of talking about God and acknowledges the superiority of apophatism. Cf. Vladimir Lossky, op. cit., p. 55, Dumitru Stăniloae, op. cit., pp. 261-262.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 John Chryssavgis, Repentance and Confession - Introduction, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, accessed 2008-03-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 An Online Orthodox Catechism, Russian Orthodox Church, accessed 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Olga Louchakova, Ontopoiesis and Union in the Jesus Prayer: Contributions to Psychotherapy and Learning, in Logos pf Phenomenology and Phenomenology of Logos. Book Four - The Logos of Scientific Interrogation. Participating in Nature-Life-Sharing in Life, Springer Ed., 2006, p. 292, ISBN 1-4020-3736-8. Google Scholar: [1].

- ↑ Unite if referring to one person; reunite if talking at an anthropological level.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedkallistos-ware

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Henry, Gary, and Jonathan Montaldo. Merton and Hesychasm: The Prayer of the Heart & the Eastern Church (The Fons Vitae Thomas Merton series). Vitae, 2003. ISBN 9781887752459

- LaBauve, Maurice. Hesychasm, word-weaving, and Slavic hagiography: The literary school of Patriarch Euthymius. Hébert Sagner, 1992. ISBN 9783876905303

- Leloup, Jean-Yves. Being Still: Reflections on an Ancient Mystical Tradition. Paulist Press, 2003. ISBN 9780809141777

- Markides, Kyriacos C. The Mountain of Silence: A Search for Orthodox Spirituality. Image, 2002. ISBN 9780385500920

- Meyendorff, John. Gregory Palamas: The Triads (Classics of Western Spirituality). Paulist Press; New Ed edition, 1982. ISBN 9780809124473

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.