Raymond, Henry Jarvis

({{Contracted}}) |

(→Legacy) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

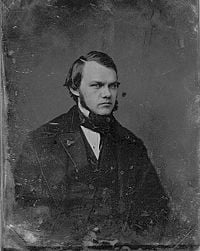

[[Image:Henry Jarvis Raymond.jpg|thumb|200 px|Henry Jarvis Raymond]] | [[Image:Henry Jarvis Raymond.jpg|thumb|200 px|Henry Jarvis Raymond]] | ||

| − | '''Henry Jarvis Raymond''' ( | + | '''Henry Jarvis Raymond''' (1820–1869), born near Lima, New York, graduated from the [[University of Vermont]], and began his journalistic career by working for the legendary editor [[Horace Greeley]]. Raymond is perhaps best known, however, for being the founder of the ''[[New York Times]]'', which greatly influenced the way news was reported. As well as having an extremely influential journalistic career, Raymond also had a passion for politics, and served as a New York State Assemblyman, Speaker of the Assembly, lieutenant-governor of New York, and a member of the House of Representatives. |

| − | == | + | ==Life== |

| − | Raymond | + | Raymond was born near the village of Lima in Livingston County, New York. He graduated from the [[University of Vermont]] in 1840, during which time he met his future wife, Juliette Weaver. They were married soon after Raymond's graduation, and had seven children together, only four of whom survived past childhood. |

| − | + | After college, Raymond moved to New York to pursue his journalistic career, where he remained throughout his journalistic and political career, until his death on June 18, 1869. There are several stories told about the cause of his death. One version states that Raymond died of a heart attack while in the apartment of his lover, actress Rose Eytinge. Another says that friends brought Raymond home from a party, mistaking the symptoms of a stroke for intoxication, where he died before morning.<ref>[http://www.uvm.edu/~uvmpr/vq/VQFALL01/raymond.html "Behind the Times, Ahead of the Times"] Fall 2001. Vermont Quarterly. Retrieved December 12, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | === | + | ==Work== |

| − | + | ===Journalistic Career=== | |

| + | Raymond began his journalistic career after his college graduation by working as a staff journalist for [[Horace Greeley|Greeley]]'s weekly publication the ''New Yorker''. After writing for Greeley's ''New Yorker'' for a year or so, Raymond worked on another Greeley publication, a daily newspaper called the ''Tribune'', where he worked as assistant editor. Later, he would gain further editorial experience by working on the old-fashioned and political ''Courier and Enquirer''. | ||

| − | Raymond | + | It wasn't until 1851 that Raymond and his friend George Jones were able to raise the money to make their dreams of their own newspaper become a reality. Even though previous editors had founded papers with little or no money, Raymond insisted on raising $100,000 (one hundred times what Greeley used to found the ''Tribune'' ten years earlier), which put the paper on a solid financial footing. On September 18, 1851, the first issue of the New York ''Daily Times'', co-founded by Jones and Raymond, was published. Later renamed ''The New York Times'' in 1857, the newspaper was one of the first to give the news calmly and reliably. Most newspapers of the time were overly concerned with hyper-emotional writing, sensationalism, and extremist personalities, reading more like tabloids than respectable newspapers.<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9062830 "Raymond, Henry Jarvis"] 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 12, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | Editorially, Raymond sought a compromise between Greeley's moralizing and the immoral sensationalism of other papers. In the first issue of the ''Times'' Raymond announced his purpose to write in temperate and measured language, and to control his emotions in his writing. "There are few things in this world which it is worth while to get angry about; and they are just the things anger will not improve." He wanted the ''Times'' to be guided by a sense of social ethics, and took great care to make sure that foreign correspondents contributed world news thoroughly, carefully, and intelligently.<ref>[http://www.bartleby.com/226/1221.html "Henry Jarvis Raymond"] 1907-21. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes. University Press. Retrieved December 12, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===New York State politics=== | |

| − | + | As Raymond matured as a journalist, his political opinions diverged from Greeley's political philosophy. The split in their relationship intensified in 1849, when Raymond was elected to the state assembly. Raymond was a member of the New York Assembly in 1850 and 1851, and in the latter year was Speaker. In 1854, Raymond was elected lieutenant-governor of the state on the [[Whig]] ticket, a position that Greeley had coveted. This victory by Raymond led to the dissolution of the political alliance of Greeley, [[Thurlow Weed]], and [[William H. Seward]], and contributed to the demise of the Whig Party. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Raymond became actively involved with the formation of the new [[Republican Party]], writing a statement of party principles called "Address to the People", which was presented at the 1856 Republican Party's convention in [[Pittsburgh]]. Raymond also served as president of the Republican National Committee from 1864-66. In 1864, he helped to prepare most of President [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s platform, and served in the [[House of Representatives]] from 1865-67. Towards the end of his political career, Raymond attacked the [[Reconstruction]] theories of fellow Republican [[Thaddeus Stevens]], who felt that states that had seceded should not be restored to their former status in the [[Union]]. Raymond expressed many of his views on the matter during his "Address and Declaration of Principles", presented at the 1866 Loyalist (or National Union) convention in Philadelphia. These actions caused him to lose favor with the Republican Party, and he was removed from the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee in 1866. Failing to be renominated by his party, he returned actively to journalism in 1867. | |

| − | |||

| − | Raymond | ||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | + | Raymond's political legacy is found in the pivotal role he played in the creation of the Republican Party, one of the most politically influential parties throughout American history. | |

| − | + | Perhaps greater than his political legacy, however, is his journalistic legacy. In founding the ''Times'', Raymond helped to define a new type of journalism. Sometimes considered the father of modern journalism, Raymond helped to create a careful, reasoned, and accurate approach that became the standard for respectable news reporting. Eschewing sensationalism and over-emotional writing, Raymond set a standard that would influence a great number of future editors. | |

==Major works== | ==Major works== | ||

In addition to the his work with the ''[[New York Times]]'', he wrote books including: | In addition to the his work with the ''[[New York Times]]'', he wrote books including: | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''History of the administration of President Lincoln: including his speeches, letters, addresses, proclamations, and messages. With a preliminary sketch of his life." By Henry J. Raymond. 1864. (Reprint 2006) Michigan Historical Reprint Series.'' ISBN 1425554709 |

| − | + | *''Disunion and slavery: a series of letters to Hon. [[W.L. Yancey]], of Alabama''. 1861. Cornell University Library ISBN 1429712589 | |

| − | *'' | ||

*''Political Lessons of the Revolution''. 1854. | *''Political Lessons of the Revolution''. 1854. | ||

| − | *''The | + | *''The life and public services of Abraham Lincoln: Together with his state papers, including his speeches, addresses, messages, letters, and proclamations; ... personal reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln''. 1865. Derby and Miller. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 19:58, 12 December 2007

Henry Jarvis Raymond (1820–1869), born near Lima, New York, graduated from the University of Vermont, and began his journalistic career by working for the legendary editor Horace Greeley. Raymond is perhaps best known, however, for being the founder of the New York Times, which greatly influenced the way news was reported. As well as having an extremely influential journalistic career, Raymond also had a passion for politics, and served as a New York State Assemblyman, Speaker of the Assembly, lieutenant-governor of New York, and a member of the House of Representatives.

Life

Raymond was born near the village of Lima in Livingston County, New York. He graduated from the University of Vermont in 1840, during which time he met his future wife, Juliette Weaver. They were married soon after Raymond's graduation, and had seven children together, only four of whom survived past childhood.

After college, Raymond moved to New York to pursue his journalistic career, where he remained throughout his journalistic and political career, until his death on June 18, 1869. There are several stories told about the cause of his death. One version states that Raymond died of a heart attack while in the apartment of his lover, actress Rose Eytinge. Another says that friends brought Raymond home from a party, mistaking the symptoms of a stroke for intoxication, where he died before morning.[1]

Work

Journalistic Career

Raymond began his journalistic career after his college graduation by working as a staff journalist for Greeley's weekly publication the New Yorker. After writing for Greeley's New Yorker for a year or so, Raymond worked on another Greeley publication, a daily newspaper called the Tribune, where he worked as assistant editor. Later, he would gain further editorial experience by working on the old-fashioned and political Courier and Enquirer.

It wasn't until 1851 that Raymond and his friend George Jones were able to raise the money to make their dreams of their own newspaper become a reality. Even though previous editors had founded papers with little or no money, Raymond insisted on raising $100,000 (one hundred times what Greeley used to found the Tribune ten years earlier), which put the paper on a solid financial footing. On September 18, 1851, the first issue of the New York Daily Times, co-founded by Jones and Raymond, was published. Later renamed The New York Times in 1857, the newspaper was one of the first to give the news calmly and reliably. Most newspapers of the time were overly concerned with hyper-emotional writing, sensationalism, and extremist personalities, reading more like tabloids than respectable newspapers.[2]

Editorially, Raymond sought a compromise between Greeley's moralizing and the immoral sensationalism of other papers. In the first issue of the Times Raymond announced his purpose to write in temperate and measured language, and to control his emotions in his writing. "There are few things in this world which it is worth while to get angry about; and they are just the things anger will not improve." He wanted the Times to be guided by a sense of social ethics, and took great care to make sure that foreign correspondents contributed world news thoroughly, carefully, and intelligently.[3]

New York State politics

As Raymond matured as a journalist, his political opinions diverged from Greeley's political philosophy. The split in their relationship intensified in 1849, when Raymond was elected to the state assembly. Raymond was a member of the New York Assembly in 1850 and 1851, and in the latter year was Speaker. In 1854, Raymond was elected lieutenant-governor of the state on the Whig ticket, a position that Greeley had coveted. This victory by Raymond led to the dissolution of the political alliance of Greeley, Thurlow Weed, and William H. Seward, and contributed to the demise of the Whig Party.

Raymond became actively involved with the formation of the new Republican Party, writing a statement of party principles called "Address to the People", which was presented at the 1856 Republican Party's convention in Pittsburgh. Raymond also served as president of the Republican National Committee from 1864-66. In 1864, he helped to prepare most of President Abraham Lincoln's platform, and served in the House of Representatives from 1865-67. Towards the end of his political career, Raymond attacked the Reconstruction theories of fellow Republican Thaddeus Stevens, who felt that states that had seceded should not be restored to their former status in the Union. Raymond expressed many of his views on the matter during his "Address and Declaration of Principles", presented at the 1866 Loyalist (or National Union) convention in Philadelphia. These actions caused him to lose favor with the Republican Party, and he was removed from the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee in 1866. Failing to be renominated by his party, he returned actively to journalism in 1867.

Legacy

Raymond's political legacy is found in the pivotal role he played in the creation of the Republican Party, one of the most politically influential parties throughout American history.

Perhaps greater than his political legacy, however, is his journalistic legacy. In founding the Times, Raymond helped to define a new type of journalism. Sometimes considered the father of modern journalism, Raymond helped to create a careful, reasoned, and accurate approach that became the standard for respectable news reporting. Eschewing sensationalism and over-emotional writing, Raymond set a standard that would influence a great number of future editors.

Major works

In addition to the his work with the New York Times, he wrote books including:

- History of the administration of President Lincoln: including his speeches, letters, addresses, proclamations, and messages. With a preliminary sketch of his life." By Henry J. Raymond. 1864. (Reprint 2006) Michigan Historical Reprint Series. ISBN 1425554709

- Disunion and slavery: a series of letters to Hon. W.L. Yancey, of Alabama. 1861. Cornell University Library ISBN 1429712589

- Political Lessons of the Revolution. 1854.

- The life and public services of Abraham Lincoln: Together with his state papers, including his speeches, addresses, messages, letters, and proclamations; ... personal reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln. 1865. Derby and Miller.

Notes

- ↑ "Behind the Times, Ahead of the Times" Fall 2001. Vermont Quarterly. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Raymond, Henry Jarvis" 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Henry Jarvis Raymond" 1907-21. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes. University Press. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Augustus Maverick. 1870. Henry J. Raymond and the New York Press for Thirty Years. Hartford.

- Davis, Elmer. History of the New York Times, 1851-1921. 1921.

- Dicken-Garcia, Hazel. 1989. Journalistic Standards in Nineteenth-Century America

- Douglas, George H. 1999. The Golden Age of the Newspaper.

- Sloan, W. David and James D. start. 2003. The Gilded Age Press, 1865-1900.

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren. 1994. The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865-1878.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- This article also copies from Newspapers, 1775 – 1860 by Frank W. Scott (1917) which is also in the public domain. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

External links

- Mr. Lincoln and New York: Henry J. Raymond. Retrieved November 5, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.