Difference between revisions of "Hathor" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Paid}}) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

In [[Egyptian mythology]], '''Hathor''' (Egyptian for "House of [[Horus]]") was an ancient cow goddess, whose wide range of attributes and associations are testament to her tremendous antiquity. She was associated with sexuality, fertility, and joy, but was also seen as the goddess of the night sky—in particular the Milky Way, which was seen as the milk that flowed from her divine udder. The name ''Hathor'' refers to her encirclement of the night sky, which was thought of as the home of [[Horus]]. Consequently, the lunar god was said to be her son. | In [[Egyptian mythology]], '''Hathor''' (Egyptian for "House of [[Horus]]") was an ancient cow goddess, whose wide range of attributes and associations are testament to her tremendous antiquity. She was associated with sexuality, fertility, and joy, but was also seen as the goddess of the night sky—in particular the Milky Way, which was seen as the milk that flowed from her divine udder. The name ''Hathor'' refers to her encirclement of the night sky, which was thought of as the home of [[Horus]]. Consequently, the lunar god was said to be her son. | ||

| − | An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was ''Mehturt'' (also spelled ''Mehurt'', ''Mehet-Weret'', and ''Mehet-uret''), meaning ''great flood'', a direct reference to her being the milky way.<ref>Pinch, 163.</ref> The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and | + | An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was ''Mehturt'' (also spelled ''Mehurt'', ''Mehet-Weret'', and ''Mehet-uret''), meaning ''great flood'', a direct reference to her being the milky way.<ref>Pinch, 163.</ref> The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and deceased kings, leading the ancient Egyptians to describe it as ''The Nile in the Sky''. Due to this, Hathor came to be identified (in some cosmologies) as the deity responsible for the yearly inundation of the [[Nile]]. |

==Hathor in an Egyptian Context== | ==Hathor in an Egyptian Context== | ||

Revision as of 02:15, 5 October 2007

In Egyptian mythology, Hathor (Egyptian for "House of Horus") was an ancient cow goddess, whose wide range of attributes and associations are testament to her tremendous antiquity. She was associated with sexuality, fertility, and joy, but was also seen as the goddess of the night sky—in particular the Milky Way, which was seen as the milk that flowed from her divine udder. The name Hathor refers to her encirclement of the night sky, which was thought of as the home of Horus. Consequently, the lunar god was said to be her son.

An alternate name for Hathor, which persisted for 3,000 years, was Mehturt (also spelled Mehurt, Mehet-Weret, and Mehet-uret), meaning great flood, a direct reference to her being the milky way.[1] The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and deceased kings, leading the ancient Egyptians to describe it as The Nile in the Sky. Due to this, Hathor came to be identified (in some cosmologies) as the deity responsible for the yearly inundation of the Nile.

Hathor in an Egyptian Context

As an Egyptian deity, Hathor belonged to a religious, mythological and cosmological belief system that developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to around 525 B.C.E.[2] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[3] The cults were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[4] Yet, the Egyptian gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “If we compare two of [the Egyptian gods] … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[5] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanent—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[6] Thus, those Egyptian gods who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Furthermore, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[7]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely defined by the geographical and calendrical realities of its believers' lives. The Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[8] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[9] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

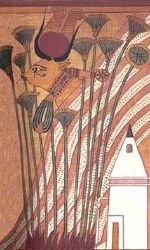

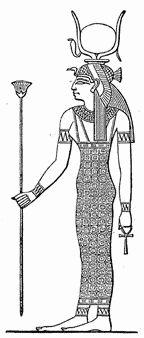

Associations, images, and symbols

Eventually, Hathor's identity as a cow, meant that she became identified with another ancient cow-goddess of fertility, Bat. It still remains an unanswered question amongst Egyptologists as to why Bat survived as an independent goddess for so long. Bat was, in some respects, connected to the Ba, an aspect of the soul, and so Hathor gained an association with the after-life. It was said that, with her motherly character, she greeted the souls of the dead in Duat, and proffered them with refreshments of food and drink. She also was sometimes described as mistress of the acropolis.

The assimilation of Bat, who was associated with the sistrum, a musical instrument, brought with it an association with music. In this form, Hathor's cult became centered in Dendera, where it was led by priests who also were dancers, singers, and entertainers.

Hathor also became associated with the menat, the turquoise musical necklace often worn by women. A hymn to Hathor says:

- Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End.

Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of Joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of Lady of the House of Jubilation, and The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy.

The worship of Hathor was so popular that more festivals were dedicated to her honor than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both men and women became her priests.

Bloodthirsty warrior

The Middle Kingdom was founded when Upper Egypt's pharaoh, Mentuhotep II, forcibly took control of Lower Egypt, which had become independent during the First Intermediate Period. The unification that had been achieved through this brutal war allowed the reign of the next pharaoh, Mentuhotep III, to be peaceful. From this foundation, Egypt once again became prosperous. During this period, the Lower Egyptians penned a memorial tale commemorating those who fell in the protracted battle and enshrining their own experience during the protracted civil war.

In the tale following the war, Ra (representing the pharaoh of Upper Egypt) was no longer respected by the people (of Lower Egypt) and they ceased to obey his authority, which made him so angry that he sent out Sekhmet (war goddess of Upper Egypt) to destroy them. Sekhmet became bloodthirsty and the slaughter was great because she could not be stopped. As the slaughter continued, fear that all of humanity would be destroyed arose among the deities and Ra was charged with stopping her. Ra poured huge quantities of blood-colored beer on the ground to trick Sekhmet. She drank so much of it—thinking it to be blood—that she became too drunk to continue the slaughter and humanity was saved. Afterward Sekhmet became loving and kind.

The gentle form that Sekhmet had become by the end of the tale was identical in character to Hathor, and so a new cult arose, at the start of the Middle Kingdom, which dualistically identified Sekhmet with Hathor, making them one goddess, Sekhmet-Hathor, with two sides. Consequently, Hathor, as Sekhmet-Hathor, was sometimes depicted as a lioness. Sometimes this joint name was corrupted to Sekhathor (also spelled Sechat-Hor, Sekhat-Heru), meaning (one who) remembers Horus (the uncorrupted form would mean (the) powerful house of Horus but Ra had displaced Horus, thus the change). The two goddesses were so different, indeed almost diametrically opposed, however, that the new identification did not last.

Wife of Thoth

When Horus became identified as Ra (Ra-Herakhty) in the evolving Egyptian pantheon, Hathor's position became unclear, since in later myths she had been the wife of Ra, but in earlier myths she was the mother of Horus. One attempt to solve this conundrum gave Ra-Herakhty a new wife, Ausaas, which meant that Hathor could still be identified as the mother of the new sun god. However, this left open the unsolved question of how Hathor could be his mother, since this would imply that Ra-Herakhty was a child of Hathor, rather than a creator. Such inconsistencies developed as the Egyptian pantheon changed over the thousands of years becoming very complex, and some were never resolved.

In areas where the cult of Thoth became strong, Thoth was identified as the creator, leading to it being said that Thoth was the father of Ra-Herakhty, thus in this version Hathor, as the mother of Ra-Herakhty, was referred to as Thoth's wife. In this version of what is called the Ogdoad cosmogony, Ra-Herakhty was depicted as a young child, often referred to as Neferhor. When considered the wife of Thoth, Hathor often was depicted as a woman nursing her child. Arising from this syncretism, the goddess Seshat, who had earlier been thought of as Thoth's wife, came to be identified with Hathor. For instance, the cow goddess came to be associated with the judgment of souls in Duat, which led to the title 'Nechmetawaj ("the (one who) expels evil"). By a homophonic coincidence, Nechmetawaj (which can also be spelled Nehmet-awai and Nehmetawy) can also be understood to mean (one who) recovers stolen goods, which resultantly came to be another of the goddess's traits.

Outside the cult of Thoth, it was considered important to retain the position of Ra-Herakhty (i.e. Ra) as self-created (via only the primal forces of the Ogdoad). Consequently, Hathor could not be identified as Ra-Herakhty's mother. Hathor's role in the process of death, that of welcoming the newly dead with food and drink, led, in such circumstances, to her being identified as a jolly wife for Nehebkau, the guardian of the entrance to the underworld and binder of the Ka. Nevertheless, in this form, she retained the name of Nechmetawaj, since her aspect as a returner of stolen goods was so important to society that it was retained as one of her roles.

Hathor outside Egypt

Hathor was worshipped in Canaan in the eleventh century B.C.E. at the holy city of Hazor (Tel Hazor), which at that time was ruled by Egypt. It seems likely that this is the same city that the Old Testament claims was destroyed by Joshua (Joshua 11:13, 21).

The Sinai Tablets show that the Hebrew workers in the mines of Sinai (ca. 1500 B.C.E.) worshiped Hathor, who they identified with their goddess Astarte. Some theories state that the golden calf mentioned in the Bible was meant to refer to a statue of the goddess Hathor (Exodus 32:4-32:6.). A major temple to Hathor was constructed by Seti II at the copper mines at Timna in Edomite Seir. Serabit el-Khadim (Arabic: سرابت الخادم) (Arabic, also transliterated Serabit al-Khadim, Serabit el-Khadem) is a locality in the south-west Sinai Peninsula where turquoise was mined extensively in antiquity, mainly by the ancient Egyptians. Archaeological excavation, initially by Sir Flinders Petrie, revealed the ancient mining camps and a long-lived Temple of Hathor.

The Greeks, who became rulers of Egypt for three hundred years before the Roman domination in 31 B.C.E., also loved Hathor and equated her with their own goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite.

Notes

- ↑ Pinch, 163.

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archaeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

External links

- Hathor Article by Caroline Seawright Retrieved Sept. 25, 2007.

- Het-Hert site, another name for Hathor Retrieved Sept. 25, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.