Faeroe Islands

| Føroyar Færøerne Faroe Islands | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Tú alfagra land mítt You, my most beauteous land | |||||

| Capital | Tórshavn 62°00′N 06°47′W | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Faroese, Danish | ||||

| Government | |||||

| - Monarch | Margrethe II | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Jóannes Eidesgaard | ||||

| Autonomous province of the Kingdom of Denmark | |||||

| - Home rule | 1948 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 1,399 km² (180th) 540 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 0.5 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - December 2006 estimate | 48,317 | ||||

| - 2004 census | 48,470 | ||||

| - Density | 34/km² 88/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $1.0 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $22,000 (2001 estimate) | ||||

| HDI (2006) | 0.9431 (high) | ||||

| Currency | Faroese króna2 (DKK)

| ||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | EST (UTC+1) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .fo | ||||

| Calling code | +298 | ||||

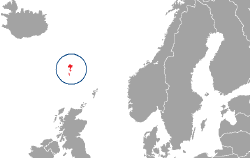

The Faroe Islands or Faeroe Islands or simply Faroes or Faeroes, meaning "Sheep Islands," are a group of islands in Northern Europe, between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, roughly equidistant between Iceland, Scotland, and Norway. They have been an autonomous region of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1948, making it a member of the Rigsfællesskab. The Faroese have, over the years, taken control of most matters except defense (though they have a native coast guard), foreign affairs and the legal system. These three areas are the responsibility of Denmark.

The Faroes have close traditional ties to Iceland, Shetland, Orkney, the Outer Hebrides and Greenland. The archipelago was politically detached from Norway in 1814. The Faroes are represented in the Nordic Council as a part of the Danish delegation.

Geography

The Faroe Islands are an island group consisting of eighteen islands off the coast of Northern Europe, between the Norwegian Sea and the north Atlantic Ocean, about halfway between Iceland and Norway; the closest neighbors being the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland. Its coordinates lie at 62°00′N 06°47′W.

Its area is 540 square miles (1,399 square km), with no major lakes or rivers. Having no shared land boundaries with any other country, there are 694 miles of coastline. There are 17 inhabited islands. The island known as Lítla Dímun is uninhabited, as are many islets and reefs.

Distances to nearest countries and islands

- Sula Sgeir (Scotland): 149 miles

- Shetland (Scotland): 174 miles

- Scotland (British Mainland): 193 miles

- Iceland: 280 miles

- Norway: 419 miles

- Ireland: 421 miles

Climate

The climate is oceanic and mild, with generally cool summers and mild winters. An overcast sky is common, as are frequent fog and heavy winds. The fog often causes air traffic delays. The islands are rugged and rocky with some low peaks; the coasts are mostly bordered by cliffs. The highest point is Slættaratindur at 2,894 ft. above sea level.

Flora and fauna

The natural vegetation of the Faroe Islands is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wild flowers, grasses, moss and lichen. Most of the lowland areas are grassland but some areas are heather, meaning open areas of uncultivated land with low-growing shrubs consistent of small, colorful, urn-shaped flowers; mainly Calluna vulgaris.

The islands are characterized by the lack of trees, due to strong westerly winds and frequent gales. A few small plantations consisting of plants collected from similar climates like Tierra del Fuego in South America and Alaska have been planted and are growing well. Sturdy trees have been planted in some of these sheltered areas.

The bird fauna of the Faroe Islands is dominated by sea-birds and birds attracted to open land such as heather, probably due to the lack of woodland and other suitable habitats. Many species have developed special Faroese sub-species such as Eider, Starling, Wren, Guillemot, and Black Guillemot.[1] Only a few species of wild land mammals are found in the Faroe Islands today, all were introduced from other locations.

Grey Seals are very common around the Faroese shores, as are several species of whales which live in the surrounding waters. Best known are the Short-finned Pilot Whales, but the more exotic Killer whales sometimes visit the Faroese fjords, a long, narrow, deep inlet of the sea between steep slopes.

History

The early history of the Faroe Islands is not well known. Irish hermit monks settled there in the sixth century, introducing sheep and oats to the islands. Saint Brendan, who lived circa 484–578, is said to have visited the Faroe Islands on two or three occasions, naming two of the islands Sheep Island and Paradise Island of Birds.

Later the Vikings replaced the Irish settlers, bringing the Old Norse language to the islands, which locally evolved into the modern Faroese language spoken today. The settlers are not thought to have come directly from Norway, but rather from the Norwegian settlements in Shetland, Orkney, and around the Irish Sea, and to have been what was called Norse-Gaels.

According to Færeyinga Saga, emigrants who left Norway to escape the tyranny of Harald I of Norway settled in the islands about the end of the ninth century. Early in the eleventh century, Sigmundur Brestirson, whose family had flourished in the southern islands but had been almost exterminated by invaders from the northern islands, escaped to Norway and was sent back to take possession of the islands for Olaf Tryggvason, king of Norway. He introduced Christianity and, though he was subsequently murdered, Norwegian supremacy was upheld. Norwegian control of the islands continued until 1380, when Norway entered the Kalmar Union with Denmark, which gradually evolved into Danish control of the islands. The reformation reached the Faroes in 1538. When the union between Denmark and Norway was dissolved as a result of the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, Denmark retained possession of the Faroe Islands.

The trade monopoly in the Faroe Islands was abolished in 1856 and the country has since developed as a modern fishing nation with its own fleet. The national awakening since 1888 was first based on a struggle for the Faroese language, and thus more culturally oriented, but after 1906 was more and more politically oriented with the foundation of the political parties of the Faroe Islands.

On April 12, 1940, the Faroes were occupied by British troops. The move followed the invasion of Denmark by Nazi Germany and had the objective of strengthening British control of the North Atlantic. In 1942–43 the British Royal Engineers built the only airport in the Faroes, Vágar Airport. Control of the islands reverted to Denmark following the war, but in 1948 a home-rule regime was implemented granting a high degree of local autonomy. The Faroes declined to join Denmark in entering the European Community (now European Union) in 1973. The islands experienced considerable economic difficulties following the collapse of the fishing industry in the early 1990s, but have since made efforts to diversify the economy. Support for independence has grown and is the objective of the government.

Politics

The government of the Faroes holds the executive power in local government affairs. The head of the government is called the Løgmaður or prime minister in English. Any other member of the cabinet is called a landsstýrismaður.

Elections are held in the municipalities, on a national level for the Løgting, and inside the Kingdom of Denmark for the Folketing. For the Løgting elections there are seven electoral districts, each one comprising a sýsla, while Streymoy is divided into a northern and southern part (Tórshavn region).

The Faroes and Denmark

The Treaty of Kiel in 1814 terminated the Danish-Norwegian union. Norway came under the rule of the King of Sweden, but the Faeroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland remained as possessions of Denmark. Subsequently, the Løgting was abolished (1816), and the Faeroe Islands were to be governed as a regular county of Denmark, with the Amtmand as its head of government. In 1851 the Løgting was resurrected, but served mainly as an advisory power until 1948.

At the end of the Second World War a portion of the population favored independence from Denmark, and on September 14, 1946 a public election was held on the question of secession. It was not considered a referendum, as the parliament was not bound to follow the decision of the vote. This was the first time that the Faeroese people were asked if they favored independence or if they wanted to continue as a part of the Danish kingdom. The outcome of the vote produced a small majority in favor of secession, but the coalition in parliament could not reach a resolution on how this election should be interpreted and implemented; because of these irresolvable differences the coalition fell apart.

A parliamentary election was again held just a few months later, in which the political parties that favored staying in the Danish kingdom increased their share of the vote and formed a coalition. Based on this increased share of the votes, they chose to reject secession. Instead, a compromise was made and the Folketing passed a home-rule law, which came into effect in 1948. The Faeroe Islands' status as a Danish county was brought to an end with the home-rule law; the Faroe Islands were given a high degree of self-governance, supported by a substantial annual subsidy from Denmark.

The islanders are fairly evenly split between those favoring independence and those who prefer to continue as a part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Within both camps there is, however, a wide range of opinions. Of those who favor independence, some are in favor of an immediate unilateral declaration. Others see it as something to be attained gradually and with the full consent of the Danish government and the Danish nation. In the unionist camp there are also many who foresee and welcome a gradual increase in autonomy even as strong ties to Denmark are maintained.

HERE

The Faeroes and the European Union

As explicitly asserted by both Rome treaties, the Faeroe Islands are not part of the European Union. Moreover, a protocol to the treaty of accession of Denmark to the European Communities stipulates that Danish nationals residing in the Faroe Islands are not to be considered as Danish nationals within the meaning of the treaties. Hence, Danish people living in the Faroes are not citizens of the European Union. (Other EU nationals living there remain EU citizens.) The Faroes are not covered by the Schengen free movement agreement, but there are no border checks when traveling between the Faroes and any Schengen country [citation needed].

Regions and municipalities

Administratively, the islands are divided into 34 municipalities within which 120 or so cities and villages lie.

Traditionally, there are also the six sýslur ("regions") Norðoyar, Eysturoy, Streymoy, Vágar, Sandoy and Suðuroy. Although today sýsla technically means "police district," the term is still commonly used to indicate a geographical region. In earlier times, each sýsla had its own ting or assembly.

Economy

After the severe economic troubles of the early 1990s, brought on by a drop in the vital fish catch and poor management of the economy, the Faroe Islands have come back in the last few years, with unemployment down to 5% in mid-1998.In 2006 unemployment declined to 3%, one of the lowest rates in Europe. Nevertheless, the almost total dependence on fishing means that the economy remains extremely vulnerable. The Faroese hope to broaden their economic base by building new fish-processing plants. As an agrarian society, other than fishing, the raising of sheep is the main industry of the islands. Petroleum found close to the Faroese area gives hope for deposits in the immediate area, which may provide a basis for sustained economic prosperity.

Since 2000, new information technology and business projects have been fostered in the Faroe Islands to attract new investment. The introduction of Burger King in Tórshavn was widely publicized and a sign of the globalization of Faroese culture. However, it is not yet known whether these projects will succeed in broadening the islands' economic base. While having one of the lowest unemployment rates in Europe, this should not necessarily be taken as a sign of a recovering economy, as many young students move to Denmark and other countries once they are finished with high school. This leaves a largely middle-aged and elderly population that may lack the skills and knowledge to fill newly developed computing positions on the Faroes.

Transportation

Due to the rocky terrain and relatively small size of the Faroe Islands, its transportation system has never been as extensive as other places of the world. This situation has changed, and today the infrastructure has been developed extensively. Some 80% of the population of the islands is connected by under-ocean tunnels, bridges, and causeways which bind the three largest islands and three other large islands to the northeast together, while the other two large islands to the south of the main area are connected to the main area with new fast ferries. There are good roads that lead to every village in the islands, except for seven of the smaller islands with only one village each. Vágar Airport has scheduled service to destinations from Vágoy Island. With the largest Faroese airline being Atlantic Airways.

Demographics

The vast majority of the population are ethnic Faroese, of Norse and Celtic descent.[2]

Recent DNA analyses have revealed that Y chromosomes, tracing male descent, are 87% Scandinavian.[3] The studies show that mitochondrial DNA, tracing female descent, is 84% Scottish / Irish.[4]

Of the approximately 48,000 inhabitants of the Faroe Islands (16,921 private households (2004)), 98% are realm citizens, meaning Faroese, Danish, or Greenlandic. By birthplace one can derive the following origins of the inhabitants: born on the Faroes 91.7%, in Denmark 5.8%, and in Greenland 0.3%. The largest group of foreigners is Icelanders comprising 0.4% of the population, followed by Norwegians and Polish, each comprising 0.2%. Altogether, on the Faroe Islands there are people from 77 different nationalities.

Faroese is spoken in the entire country as a first language. It is not possible to say exactly how many people worldwide speak the Faroese language. This is for two reasons: Firstly, many ethnic Faroese live in Denmark and few who are born there return to the Faroes with their parents or as adults. Secondly, there are some established Danish families on the Faroes who speak Danish at home.

The Faroese language is one of the smallest of the Germanic languages. Faroese grammar is most similar to Icelandic and Old Norse. In contrast, spoken Faroese differs much from Icelandic and is closer to Norwegian dialects from the west coast of Norway. In the twentieth century, Faroese became the official language. Since the Faroes are a part of the Danish realm, Danish is taught in schools as a compulsory second language. Faroese language policy provides for the active creation of new terms in Faroese suitable for modern life.

Population Trends

If the first inhabitants of the Faroe Islands were Irish monks, then they must have lived as a very small group of settlers. Later, when the Vikings colonized the Islands, there was a considerable increase in the population. However, it never exceeded 5,000 until the eighteenth century. Around 1,349 people, about half of the islands' population, died of the plague.

Only with the rise of the deep sea fishery (and thus independence from difficult agriculture) and with general progress in the health service was rapid population growth possible in the Faroes. Beginning in the eighteenth century, the population increased tenfold in 200 years.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Faroe Islands entered a deep economic crisis with heavy, noticeable emigration; however, this trend reversed in subsequent years to a net immigration.

Urbanization and Regionalization

The Faroese population is spread across most of the country; it was not until recent decades that significant urbanization occurred. Industrialization has been remarkably decentralized, and the country has therefore maintained quite a viable rural culture. Nevertheless, villages with poor harbor facilities have been the losers in the development from agriculture to fishing, and in the most peripheral agricultural areas, also known as the the outer islands, there are scarcely any young people left. In recent decades, the village-based social structure has nevertheless been placed under pressure; instead there has been a rise in interconnected "centers" that are better able to provide goods and services than the badly connected periphery. This means that shops and services are now relocating en masse from the villages into the centers, and in turn this also means that slowly but steadily the Faroese population concentrates in and around the centers.

In the nineties the old national policy of developing the villages (Bygdamenning) was abandoned, and instead the government started a process of regional development (Økismenning). In the nineties the term "region" referred to the large islands of the Faroes. Nevertheless the government was not able to press through the structural reform of merging the small rural municipalities in order to create sustainable, decentralized entities that could drive forward the regional development. As the regional development has been difficult on the administrative level, the government has instead made heavy investments in infrastructure, interconnecting the regions.

Altogether it becomes less meaningful to perceive the Faroes as a society based on various islands and regions. The huge investments in roads, bridges and sub-sea tunnels (see also Transportation in the Faroe Islands) have tied together the islands, creating a coherent economic and cultural sphere that covers almost 90% of the entire population. From this perspective it is reasonable to perceive the Faroes as a dispersed city or even to refer to it as the Faroese Network City.

Religion

According to Færeyinga Saga, Sigmundur Brestisson brought Christianity to the islands in 999. However, archaeology from a site in Leirvík suggests that Celtic Christianity may have arrived at least 150 years earlier.[citation needed] The Faroe Islands' church Reformation was completed on January 1, 1540. According to official statistics from 2002, 84.1% of the Faroese population are members of the state church, the Faroese People's Church (Fólkakirkjan), a form of Lutheranism. Faroese members of the clergy who have had historical importance include V. U. Hammershaimb (1819-1909), Frederik Petersen (1853-1917) and, perhaps most significantly, Jákup Dahl (1878-1944), who had a great influence in making sure that the Faroese language was spoken in the church instead of Danish.

In the late 1820s, the Christian Evangelical religious movement, the Plymouth Brethren, was established in England. In 1865, a member of this movement, William Gibson Sloan, travelled to the Faroes from Shetland. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the Faroese Plymouth Brethren numbered thirty. Today, approximately 10% of the Faroese population are members of the Open Brethren community (Brøðrasamkoman). About 5% belong to other Christian churches, such as the Adventists, who operate a private school in Tórshavn. Jehovah's Witnesses also number four congregations (approximately 80 to 100 members). The Roman Catholic congregation comprises approximately 170 members. The municipality of Tórshavn operates their old Franciscan school. There are also around fifteen Bahá'ís who meet at four different places. Unlike Iceland, there is no organized Ásatrú community.

The best known church buildings in the Faroe Islands include St. Olafs Church and the unfinished Magnus Cathedral in Kirkjubøur; the Vesturkirkjan and the Maria Church, both of which are situated in Tórshavn; the church of Fámjin; the octagonal church in Haldarsvík; Christianskirkjan in Klaksvík and also the two pictured here.

In 1948, Victor Danielsen (Plymouth Brethren) completed the first Bible translation. It was translated into Faroese from different modern languages. Jacob Dahl and Kristian Osvald Viderø (Fólkakirkjan) completed the second translation in 1961. The latter was translated from the original languages into Faroese.

Culture

The Nordic House in the Faroe Islands

The Nordic House in the Faroe Islands (in Faroese Norðurlandahúsið) is the most important cultural institution in the Faroes. Its aim is to support and promote Nordic and Faroese culture, locally and in the Nordic region. Erlendur Patursson (1913-1986), a former Faroese member of the Nordic Council, brought forward the idea of a Nordic cultural house in the Faroe Islands. A Nordic competition for architects was held in 1977, in which 158 architects participated. Winners were Ola Steen from Norway and Kolbrún Ragnarsdóttir from Iceland. By staying true to folklore, the architects built the Nordic House to resemble an enchanting hill of elves. The house opened in Tórshavn in 1983. The Nordic House is a cultural organization under the Nordic Council of Ministers. The Nordic House is run by a steering committee of eight, of which three are Faroese and five from the other Nordic countries. There is also a local advisory body of fifteen members, representing Faroese cultural organizations. The House is managed by a director appointed by the steering committee for a four-year term.

Whaling

Whaling in the Faroe Islands has been practiced since at least the tenth century.[5] It is regulated by Faroese authorities and approved by the International Whaling Commission. Around 950 Long-finned Pilot Whales are killed annually, mainly during the summer. Occasionally, other species are hunted as well, such as the Northern Bottlenose Whale and Atlantic White-sided Dolphin. The hunts, called "grindadráp" in Faroese, are non-commercial and are organized on a community level; anyone can participate. The hunters first surround the pilot whales with a wide semi-circle of boats. The boats then drive the pilot whales slowly into a bay or to the bottom of a fjord.

Most Faroese consider the hunt an important part of their culture and history. However, animal rights groups criticize the hunt as being cruel and unnecessary.[6] [7] The hunters claim in return that most journalists do not exhibit sufficient knowledge of the catch methods or its economic significance.[8]

Music

The Faroe Islands have a very active music scene. The islands have their own symphony orchestra, the classical ensemble Aldubáran and many different choirs; the most well-known being Havnarkórið. The most well-known Faroese composers are Sunleif Rasmussen and the Dane Kristian Blak.

The first Faroese opera ever is entitled Í Óðamansgarði (The Madman´s Garden), by Sunleif Rasmussen which opened on the October 12, 2006, at the Nordic House. The opera is based on a short story by the writer William Heinesen.

Young Faroese musicians who have gained much popularity recently are Eivør (Eivør Pálsdóttir), Lena (lena Andersen), Teitur (Teitur Lassen), Høgni Lisberg and Brandur Enni.

Well-known bands include Týr, Goodiepal, Gestir, Marius, 200 and the former band Clickhaze.

The festival for contemporary and classical music, Summartónar, is held each summer. Large open-air music festivals for popular music with both local and international musicians participating are G! Festival in Gøta in July and Summarfestivalurin in Klaksvík in August.

Traditional food

Traditional Faroese food is mainly based on meat and potatoes and uses few fresh vegetables. Mutton is the basis of many meals, and one of the most popular treats is skerpikjøt, well aged, wind-dried mutton which is quite chewy. The drying shed, known as a hjallur, is a standard feature in many Faroese homes, particularly in the small towns and villages. Other traditional foods are ræst kjøt (semi-dried mutton) and ræstur fiskur, matured fish. Another Faroese specialty is Grind og spik, pilot whale meat and blubber. Well into the last century meat and blubber from the pilot whale meant food for a long time. Fresh fish also features strongly in the traditional local diet, as do seabirds, such as Faroese puffins, and their eggs.

Notes

- ↑ Aurora Boreal. The Faroese Fauna Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ↑ Highly discrepant proportions of female and male Scandinavian and British Isles ancestry within the isolated population of the Faroe Islands, http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v14/n4/full/5201578a.html, Thomas D Als, Tove H Jorgensen, Anders D Børglum, Peter A Petersen, Ole Mors and August G Wang, 25 January 2006

- ↑ The origin of the isolated population of the Faroe Islands investigated using Y chromosomal markers, http://www.springerlink.com/content/4yuhf5m7a22gc4qm/, Tove H. Jorgensen, Henriette N. Buttenschön, August G. Wang, Thomas D. Als, Anders D. Børglum and Henrik Ewald1, April 8 2004.

- ↑ Wang, C. August. 2006. Ílegur og Føroya Søga. In: Frøði pp.20-23

- ↑ An Introduction to the History of Whaling. WDCS. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ Whales and whaling in the Faroe Islands. Faroese Government. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ Why do whales and dolphins strand?. WDCS. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ Dolphins are hunted for sport and fertilizer. ABC News (2006-07-28). Retrieved 2006-12-05.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Irvine, David E. G., Ian Tittley, W. F. Farnham, Peter W. G. Gray, and James H. Price. 1982. Seaweeds of the Faroes 1: The flora. London: British Museum of Natural History. pages 109 - 131.

- Irvine, David E. G., Ian Tittley, W. F. Farnham, Peter W. G. Gray, and James H. Price. 1982. Seaweeds of the Faroes 2: Sheltered fjords and sounds. Bull. British Museum of Natural History. pages 133 - 151.

- Schei, Liv Kjørsvik, and Gunnie Moberg. 1991. The Faeroe Islands. John Murray. ISBN 0719550092

External links

- Prime Minister's Office. Prime Minister's Office Official site. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- SmugMug. Gallery of Faroe Islands. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Hagstova Foroya. Statistics of Faroese Community. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- National Bank. Faroese Banknotes. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Visit Faroe Islands. Tourist Site. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Framtak. Informative Site. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Frantisek Staud's Gallery. Photo-gallery. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Norden. Offical Site of the Nordic House of the Faroe Islands. Retrieved October 24, 2007

- Faroe Photos. Photo-gallery. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Faroe Nature. Faroes Informative Nature Website. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- The New York Times. Into the Mystical Unreal Reality of the Faroe Islands. Stephen Metcalf. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Offical Faroe Photo. Photo-gallery of the Faroe Islands. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.