Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Ellen Gould White" - New World

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) m (intro dates) |

m ({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{epname}} | {{epname}} | ||

| − | + | {{Contracted}} | |

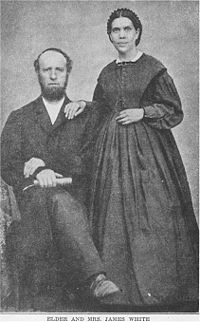

[[Image:James_and_Ellen_White.jpg|right|200px|thumb|James and Ellen White.]]'''Ellen Gould White''' (''née'' Harmon) (November 26, 1827 - July 16,1915) was an American religious leader like [[Mary Baker Eddy]] and [[Joseph Smith, Jr.]], whose prophetic ministry was instrumental in founding the Sabbatarian Adventist movement that led to the rise of the [[Seventh-day Adventist Church]]. | [[Image:James_and_Ellen_White.jpg|right|200px|thumb|James and Ellen White.]]'''Ellen Gould White''' (''née'' Harmon) (November 26, 1827 - July 16,1915) was an American religious leader like [[Mary Baker Eddy]] and [[Joseph Smith, Jr.]], whose prophetic ministry was instrumental in founding the Sabbatarian Adventist movement that led to the rise of the [[Seventh-day Adventist Church]]. | ||

Revision as of 13:58, 14 August 2006

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon) (November 26, 1827 - July 16,1915) was an American religious leader like Mary Baker Eddy and Joseph Smith, Jr., whose prophetic ministry was instrumental in founding the Sabbatarian Adventist movement that led to the rise of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Followers of Ellen G. White regard her as a modern-day prophet. Her restorationist writings showcase the hand of God in Seventh-day Adventist history. This cosmic conflict, referred to as the "great controversy theme," is foundational to the development of Seventh-day Adventist theology. Her involvement with other Sabbatarian Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White would create a nucleus of believers around which a core group of shared beliefs would emerge. Ellen White believed that Jesus Christ would return to this earth soon to claim his remnant people and take them to heaven.

White was a controversial figure within her own lifetime. She claimed to receive a vision soon after the Millerite Great Disappointment. In the context of many other visionaries, she was known for her conviction and fervent faith. With the sole exception of Agatha Christie, White is said to be the most translated female writer in the history of literature and the most translated American author of either gender.[1] Her writings covered topics of theology, evangelism, Christian lifestyle, education and health (she also advocated vegetarianism). She was a leader who emphasized education and health and promoted establishment of schools and medical centers. During her lifetime she wrote more than 5,000 periodical articles and 40 books; but today, including compilations from her 50,000 pages of manuscript, more than 100 titles are available in English. Among her works is the popular Christian book, Steps to Christ.

Adherents to denominations originating from Ellen White's teachings number approximately fourteen million.

Early life, family, and religious experiences

On her way home from school at the age of 9 years, Ellen Harmon was "seriously injured" when she was struck in the nose by a rock thrown by a schoolmate. Severely traumatized, she remained unconscious for three weeks. This injury prevented her from being able to continue her education. The two or three years of education she had received was quite typical for an American girl during the 1830s.[2]

In 1840, at age 12, her family became involved with the Millerite movement. Through attending William Miller lectures, she felt that she was a guilty sinner, and was filled with terror about being eternally lost. She describes herself as spending nights in tears and prayer, and being in this condition for several months. Historian Merlin Burt points to a three-step conversion process. She was baptized by John Hobart in Casco Bay in Portland, Maine, and eagerly awaited for Jesus to come again. After her conversion, in her later years, she referred to this as the happiest time of her life. Her family's involvement with Millerism caused the disfellowship of her entire family from the Methodist church they attended.[3]

Early Ministry 1844-1860

It was shortly after the Great Disappointment in December 1844 that Ellen White wrote that she received her first vision. She stated that she was with five other women in the home of Mrs. Haines in Portland, Maine. Her first vision was a depiction of the Adventist people following Jesus, marching to the city (heaven). This vision was taken by those around her as an encouraging sign after the devastation of the Great Disappointment. She was encouraged both in visions and by fellow church members to more broadly share her message, which she did through public speaking, articles in religious periodicals, and eventually early broadsides and pamphlets.[4]

Ellen White described the vision experience as involving a bright light which would surround her. In these visions she would be in the presence of Jesus or angels, who would show her events (historical and future) and places (on earth, in heaven, or other planets), or give her information. She described the end of her visions as involving a return to the darkness of the earth.

The transcriptions of White's visions generally contain theology, prophecy, or personal counsels to individuals or to Adventist leaders. One of the best examples of her personal counsels is found in a series of books entitled Testimonies for the Church that contains edited testimonies published for the general edification of the church. The spoken and written versions of her visions played a significant part in establishing and shaping the organizational structure of the emerging Sabbatarian Adventist Church. Her visions and writings continue to be used by church leaders in developing the church's ethical standards and policies, and for devotional reading.

On March 14, 1858, in Lovett's Grove, Ohio, White received a vision while attending a funeral service. On that day James White wrote that "God manifested His power in a wonderful manner" adding that "several had decided to keep the Lord's Sabbath and go with the people of God." In writing about the vision, she stated that she received practical instruction for church members, and more significantly, a cosmic sweep of the conflict "between Christ and His angels, and Satan and his angels." Ellen White would expand upon this great controversy theme which would eventually culminate in the Conflict of the Ages series.[5]

Middle Life 1861-1881

From 1861 to 1881 Ellen White's prophetic ministry became increasingly recognized among Sabbatarian Adventists. Her frequent articles in the "Review and Herald" and other church publications were a unifying influence to the fledgling church. She supported her husband in the church's need for formal organization. The result was the organization of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1863. During the 1860s and 1870s the Whites participated in the founding of the denomination's first medical institution (1866) and school (1874). Her husband James White died in 1881.

Later Ministry 1882-1901

After 1882 Ellen White was assisted by a close circle of friends and associates. She employed a number of literary assistants who would help her in preparing her writings for publications. She also carried on an extensive correspondence with church leaders. From 1885-1887 she traveled to Europe on her first international trip. Upon her return she promoted E. J. Waggoner and A. T. Jones, young ministers, in preparation for a more christocentric theology for the church. When church leaders resisted, she was sent to Australia as a missionary (from 1891-1900).

Final Years of Ministry and Death 1902-1915

Ellen White returned to the United States in 1900. At first she thought her stay would be temporary and she called for church re-organization at the pivotal 1901 General Conference Session. During her later years she wrote extensively for church publications and wrote her final books, including a new edition with historical revisions expounding the title, "The Great Controversy" (1911). During her final years she would travel less frequently as she concentrated upon writing her last works for the church.

Legacy

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is generally split as to how to regard her writings. Some devout Adventists believe that her writings are inspired and continue to have relevance for the church today. Others believe that her writings have devotional value only. The majority of Adventists fall somewhere within this continuum. Seventh-day Adventists began to discuss her writings at the 1919 Bible Conference, soon after her death. During the 1920s the church adopted a Fundamentalist stance toward inspiration. However during the 1940s and 1950s church leaders such as Le Roy Edwin Froom and Roy Allan Anderson attempted to help evangelicals understand Seventh-day Adventists better; they engaged in an extended dialogue that resulted in the publication of "Questions on Doctrine" (1956) that explained Adventists beliefs in evangelical language. Some Adventists such as Bert B. Beach continue to try to raise the Adventist profile among evangelicals.

Adventist Statement of Belief About the Spirit of Prophecy

Early Sabbatarian Adventists, many of whom had come out of the Christian Connexion were anti-creedal. In the 1980 statement of fundamental beliefs, which are only meant to be a statement of "Present Truth" and therefore not dogma, Ellen G. White is referenced in the fundamental belief on spiritual gifts. This doctrinal statement says:

"One of the gifts of the Holy Spirit is prophecy. This gift is an identifying mark of the remnant church and was manifested in the ministry of Ellen G. White. As the Lord's messenger, her writings are a continuing and authoritative source of truth which provide for the church comfort, guidance, instruction, and correction. They also make clear that the Bible is the standard by which all teaching and experience must be tested. (Joel 2:28, 29; Acts 2:14-21; Heb. 1:1-3; Rev. 12:17; 19:10.)" [6]

Ellen G. White's writings are considered divinely inspired but not on a par with the Bible. Seventh-day Adventists believe that her writings are subject to the Bible's authority.

Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

The Ellen G. White Estate, Inc., was formed as a result of Ellen G. White's will. It consisted of a small group of church leaders who formed a self-perpetuating board. The board continues to exist and manages a staff that includes a director, associates, and a small support staff at the main office located at the Seventh-day Adventist Church headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland. Branch Offices are located at Andrews University, Loma Linda University, and Oakwood College. There are many additional research centers located throughout the remaining divisions of the world church. The mission of the White Estate is to promote Ellen White's writings within the church. A secondary and related mission is to translate and make these writings available around the world. In 2000 the General Conference in world session expanded the mission of the White Estate to include a responsibility for promoting Adventist history for the world church.

Adventist Historic Sites

Several of Ellen G. White's homes are historic sites. The first home that she and her husband owned is now part of the Historic Adventist Village in Battle Creek, Michigan.[7] Her other homes are privately owned with the exception of her home in Cooranbong, Australia, which she named "Sunnyside," and her last home in Saint Helena, California, which she named "Elmshaven"[8]. These latter two homes are owned by the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the "Elmshaven" home is also a National Historic Landmark.

Major Teachings

This section needs to be expanded to include sections about health reform, education, church organization, and various other aspects of theology.

Arguments for and Against the Validity of Ellen G. White's Writings

Criticisms

Soon after Ellen Harmon's first vision in 1845 doubts were cast as to the reliability and authenticity of her visions. While there would be numerous critics during her lifetime, the most prominent critic was D.M. Canright. His criticisms are summarized in his 1919 book, Life of Mrs. E.G. White, Seventh-day Adventist Prophet: Her False Claims Refuted. The criticisms found in this book synthesize those of all previous critics and is the basic text for critics of Ellen G. White. Some of the most prominent criticisms include:

- Mental Illness: Critics argue that Ellen G.White had a traumatic brain injury and various neurologists have commented that this may have caused partial complex seizures. They suggest that her visions were actually hallucinations and delusions during non-motor seizures which that led her to believe that she had visions of God.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

- Plagiarism: Many critics have also accused Ellen White of plagiarism. One such was Walter Rea, who argued against the "original" nature of her supposed revelations in his The White Lie. A more recent examination of the plagariasm charges with a specific focus on Ellen White's teachings on health reform can be found Ronald Numbers' Ellen White: Prophetess of Health.[15] In this text Numbers argues that her understanding of health reform was simply plagarized from other health reformers and therefore did not come from divine revelation.

- Failed prophecy: [16]

- Denial of the Trinity: Some critics have asserted that Ellen White denied the Trinity. Adventists, for their part, credit her with bringing the Seventh-day Adventist church into a progressive awareness of the Trinity during the 1890s. Some critics assert that her descriptions of the godhead are Tritheistic. The anti-trinitarian teaching was common among the early Adventists, including White's husband James, Joseph Bates, Uriah Smith, J. N. Loughborough and J. H. Waggoner.[17]

Responses to criticism

Seventh-day Adventists have long responded to critics with arguments and assertions of their own. Typical responses to these criticisms include:

- Mental illness: Devout Seventh-day Adventists reject the charge of mental illness or that she had seizures. Instead they believe that her writings come as the result of divine revelation. In addition to a belief in the existence of spiritual gifts, Adventists point to the "overall ministry of her life" as the best proof of the genuineness of her inspiration. In addition, they believe her visions were often accompanied by supernatural phenomena. One such story relates how on several occasions witnesses recorded her holding a large Bible at arms length for extended periods of time (in one case 20-25 minutes) while she quoted Scriptural passages out loud; she would trace the verses in the Bible with her free hand as she spoke the words, and was apparently unaware of other people in the room. During such incidents, Adventists claim, several skeptics attempted to pull her arm down, as well as double-check the verses she was speaking aloud against the verses she traced with her finger. The story concludes that these unbelievers could not pull her arm down, and the verses were verbatim quotations from the Bible.

- Plagiarism: Adventists believe that her use of sources typical for a nineteenth-century writer and that her use of other authors was limited; they generally believe that "she was in control of her sources and that her sources did not control her." Adventists argue that it became increasingly normative to cite sources during her lifetime, and that Ellen G. White subsequently revised her books, changed passages to include quotations from authoritative writers, and at times deleted passages when an author could not be found. When the plagiarism charge ignited a significant debate within the Adventist church during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the General Conference commissioned a major study by Fred Veltman. The ensuing project became known as the "'Life of Christ' Research Project." The results are available at the General Conference Archives web site. David J. Conklin, among others, undertook the refutation of the accusations of plagiarism[18].

- Failed prophecy: Adventist apologists state that some prophecy, including Bible prophecy, can be conditional. Some, for instance, have suggested that a passage in "Testimonies" refers to the destruction of buildings at the end of time refers to the terrorist attack on New York City on September 11, 2001. However the Ellen G. White Estate has rejected this interpretation. Recently a number of apologetic books have been published by the church arguing for the validity of her prophetic gift. Two examples include Don McMahon's book examining the accuracy of Ellen White's medical statements and Graeme Bradford's book Prophets are human.

- Denial of the Trinity: Many Adventists argue that, while she never used the terms "Trinity" or "Triune" in her published writings, Ellen White did use the term "trio" (as in Evangelism pp. 613-617) and was Trinitarian in her views. The Seventh-day Adventist Church, in which her writings are influential, is Trinitarian in its theology.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Arthur L. White (August, 2000). Ellen G. White: A Brief Biography. Ellen G. White Estate. Retrieved 2006-03-06.

- ↑ Ellen G. White (1860). Spiritual Gifts, vol. 2. Steam Press of the Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association.

- ↑ Merlin D. Burt (1998). Ellen G. Harmon's Three Step Conversion Between 1836 and 1843 and the Harmon Family Methodist Experience.. Term paper, Andrews University.

- ↑ Ellen G. White (1922). Christian Experience and Teachings of Ellen G. White, pg. 57-61.. Review and Herald.

- ↑ Ellen G. White (1858). Spiritual Gifts, vol. 2, pg. 266-272.. James White.

- ↑ http://www.adventist.org/beliefs/fundamental/

- ↑ Adventist Heritage Site

- ↑ Elmshaven website

- ↑ Gregory Holmes and Delbert Hodder(1981).Ellen G.White and the Seventh Day Adventist Church:Visions or Partial Complex Seizures?Journal of Neurology,31(4):160-161.

- ↑ E.L.Altshuler(2002).Did Ezekiel have temporal lobe epilepsy.Archinves of General Psychiatry,59(6)561-652.

- ↑ A. W. Beard. (1963). The schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy: Physical aspects. The Journal of Psychiatry, 109:113-129.

- ↑ R.Dewhust and A. Beard. (2003). Sudden religions conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy.Epilepsy and Behavior. 4(1):78-87.

- ↑ B. K. Puri.(2001). SPECT neuroimaging in schizophrenia with religious delusions.International Journal of Psychophysiology, 40(2):143-148

- ↑ J.Wuerfel.(2004) Religion is associated with hippocampal but not amygdala volumes in patients with refractory epilepsy.Journal of Neurology, Neuropsychiatry, and Neurosurgery, 75(4):640-642.

- ↑ Ronald Numbers (1992). Prophetess of Health: Ellen G. White and the Origins of Seventh-Day Adventist Health Reform. University of Tennessee Press.

- ↑ Prophecy Blunders of Ellen G. White

- ↑ History of the Trinity Doctrine. Retrieved 2006-04-27.

- ↑ An Analysis of the Literary Dependency of Ellen White

17 See also: http://www.sdanet.org/atissue/trinity/index.htm

Biography

No authoritative biography of Ellen G. White exists. The most extensive is the six-volume "Ellen G. White: A Biography" written by her grandson, Arthur L. White (1981-1985). The most authoritative work to-date is Ronald L. Number's analysis of Ellen G. White's health reform teachings in the context of other nineteenth-century health reformers "Ellen G. White: Prophetess of Health," rev. ed. (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee, 1992). Thousands of articles and books have been written about various aspects of Ellen G. White's life and ministry. A large number of these can be found in the libraries at Loma Linda University and Andrews University—the two primary Seventh-day Adventist institutions with major research collections about Adventism.

For a listing of most of these books, periodical articles, theses, and dissertations see Gary Shearer's Index to Bibliographies on SDA and Millerite History under" White"( updated periodically): http://library.puc.edu/heritage/bib-index.shtml

External links

Official Ellen G. White Estate

- Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

- Issues and Answers Regarding Ellen White and Her Writings

- Ellen G. White Photographs

- Loma Linda University Ellen G. White Estate Branch Office

- Andrews University Ellen G. White Estate Branch Office

Apologists

- Answers for the Critics

- Examines the Critics Allegations

- What About Ellen G. White?

- Jud Lake's Adventist Apologetics Web Site

Critics

Writings Online

- Major books (from the White Estate page)

- The Complete Published Writings of Ellen G. White

- Truth for the End of Time, audio recordings of major Ellen White books in mp3 format

- Adventist Archives Contains many articles written by Ellen White

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.