Lange, Dorothea

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Dorothea Lange''' (May 25 1895 – October 11 1965) was an influential [[United States|American]] documentary [[photographer]] and [[photojournalist]], best known for her [[Dust Bowl]] | + | '''Dorothea Lange''' (May 25 1895 – October 11 1965) was an influential [[United States|American]] documentary [[photographer]] and [[photojournalist]], best known for her [[Dust Bowl]] photographs, taken throughout the American south and the west, chronicalling the hard scrabble lives of migrant works. Lange's photographs gave a human face to a dark chapter in [[United States|America]] history - the [[Great Depression]]. Her pictures of mothers and fathers, of the homeless, of those in soup lines, of children in ragged clothing, not only profoundly influenced the development of [[documentary photography]] but also of social policies under President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]'s [[New Deal]] administration. She photographed everyday Americans; their strength and their resolve, and the bonds of family and community that helped them to survive difficult times. |

With her second husband, Paul Taylor an expert in farming and migratory labor, she travelled the world contributing, through her work, to the new era of global [[communication]]s that was burgeoning after [[World War II]] and to the developing concept of an international family of man. | With her second husband, Paul Taylor an expert in farming and migratory labor, she travelled the world contributing, through her work, to the new era of global [[communication]]s that was burgeoning after [[World War II]] and to the developing concept of an international family of man. | ||

==Early life and career== | ==Early life and career== | ||

| − | Born in [[Hoboken, New Jersey]], her birth name was '''Dorothea Margarette Nutzhorn'''. After her father's abandonment of the family she and her siblings dropped the patronym Nutzhorn and adopted their mother's maiden name of Lange. Another childhood trauma for Lange was the contraction of polio in 1902, at age seven. Like other polio victims before treatment was available, Lange emerged with a weakened right leg and dropped foot. Although she compensated well for her disability, she always walked with a limp. | + | Born in [[Hoboken, New Jersey]], her birth name was '''Dorothea Margarette Nutzhorn'''. After her father's abandonment of the family she and her siblings dropped the patronym Nutzhorn and adopted their mother's maiden name of Lange. Another childhood trauma for Lange was the contraction of [[polio]] in 1902, at age seven. Like other polio victims before treatment was available, Lange emerged with a weakened right leg and dropped foot. Although she compensated well for her disability, she always walked with a limp. |

Lange once commented on her disability saying, | Lange once commented on her disability saying, | ||

:I was physically disabled, and no one who hasn't lived the life of a semi-cripple knows how much that means. I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, insructed me, helped me, and humuliated me. All those things at once.<ref>Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995</ref> | :I was physically disabled, and no one who hasn't lived the life of a semi-cripple knows how much that means. I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, insructed me, helped me, and humuliated me. All those things at once.<ref>Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995</ref> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Photography and the Great Depression== | ==Photography and the Great Depression== | ||

| − | + | After the [[Stock Market Crash of 1929]] and the ensuing [[Great Depression|depression]], Lange finding herself bored with photographing the societal elite, and turned her camera lens to the street. Her first notable picture, taken in 1934, titled ''White Angel Breadline'' shows a group of men in a food line near her studio. Her studies of the unemployed and the homeless captured the attention of not only the public but of government officials and led to her employment with the federal Resettlement Administration (RA), later called the [[Farm Security Administration]] (FSA). Another person whose interest she captured was [[Willard Van Dyke]], a founding member of the the [[avant-garde]] [[Group f/64]], who exhibited her works in his gallery. | |

| − | In December 1935, she divorced Dixon and married agricultural economist [[Paul Schuster Taylor]], Professor of Economics at the [[University of California, Berkeley]].<ref name="profile"/> Together, | + | In December 1935, she divorced Dixon and married agricultural economist [[Paul Schuster Taylor]], Professor of Economics at the [[University of California, Berkeley]].<ref name="profile"/> Together, over the next five years, they documented rural poverty including [[sharecroppers]] and migrant laborers — Taylor interviewing and gathering economic data, Lange taking photos. Some of her best photographs from this period were compiled in a book by Lange called ''American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion.'' |

| − | From 1935 to 1939, Lange's work for the RA and FSA brought the plight of the poor and forgotten — particularly | + | From 1935 to 1939, Lange's work for the RA and FSA brought the plight of the poor and forgotten — particularly, displaced farm families and migrant workers — to public attention. Distributed free to newspapers across the country, her poignant images became icons of the era. |

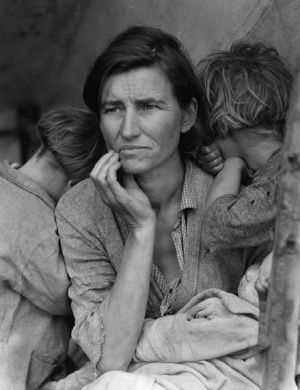

[[Image:Lange-MigrantMother02.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Lange's ''Migrant Mother'', [[Florence Owens Thompson]]]] | [[Image:Lange-MigrantMother02.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Lange's ''Migrant Mother'', [[Florence Owens Thompson]]]] | ||

| − | Lange's most well-known picture, titled "Migrant Mother," shows a weary and worried woman, a pea picker, and her hungry children. The picture resulted in aid to the pea pickers and was | + | Lange's most well-known picture, titled "Migrant Mother," (1936) shows a weary and worried woman, a pea picker, and her hungry children. The picture resulted in aid to the pea pickers and was used internationally to raise funds for medical supplies. Many years later the identity of the woman, [[Florence Owens Thompson]] was discovered, but Lange apparently never knew her name. |

In 1960, Lange spoke about her experience taking the photograph: | In 1960, Lange spoke about her experience taking the photograph: | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

==Photographing internment camps: World War II== | ==Photographing internment camps: World War II== | ||

[[Image:Japanrelocationwwii.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Lange's photo of the Japanese Relocation]] | [[Image:Japanrelocationwwii.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Lange's photo of the Japanese Relocation]] | ||

| − | In 1941, Lange was awarded a [[Guggenheim | + | In 1941, Lange was awarded a [[Guggenheim]] Fellowship for excellence in photography. After the attack on [[Pearl Harbor]], she gave up the prestigious award to record the forced evacuation of [[Japan]]ese-Americans ([[Nisei]]) to relocation camps in the American West, on assignment for the [[War Relocation Authority]] (WRA). She covered the rounding up of Japanese Americans, their evacuation into temporary assembly centers, and [[Manzanar]], the first of the permanent internment camps. To many observers, her photograph of young Japanese-American girls pledging allegiance to the flag shortly before they were sent to internment camps is a haunting reminder of this policy of detaining people without charging them with any crime simply based on their country of origin and its association through a time of war. |

| + | |||

| + | Her images were so politically sensitive when they were taken that the United States Army impounded them and they remained suppressed for many years. In 2006 nearly 800 of Lange's photos were resurrected from the National Archives and are available on the website of the Still Photographs Division, and at the Bancroft Library of the [[University of California, Berkeley]]. | ||

| − | |||

==End of life and Legacy== | ==End of life and Legacy== | ||

On her technique Lange once commented, | On her technique Lange once commented, | ||

| − | + | :For me documentary photography is less a matter of subject and more a matter of approach. The important thing is not what's photographed, but how.... My own approach is based upon three considerations. First - hands off! Whatever I photograph, I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second - a sense of place. Whatever I photograph, I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third - a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or in the present.<ref>Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995</ref> | |

| − | For me documentary photography is less a matter of subject and more a matter of approach. The important thing is not what's photographed, but how.... My own approach is based upon three considerations. First - hands off! Whatever I photograph, I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second - a sense of place. Whatever I photograph, I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third - a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or in the present.<ref>Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995</ref | ||

| − | |||

In 1952, Lange co-founded the photographic magazine ''[[Aperture (magazine)|Aperture]]''. In the last two decades of her life, Lange's health was poor. She suffered from gastric problems, including bleeding [[ulcer]]s, as well as [[post-polio syndrome]] — although this renewal of the pain and weakness of polio was not yet recognized by most physicians. She died of [[esophageal cancer]] on October 11, 1965, aged 70.<ref name="profile"/> | In 1952, Lange co-founded the photographic magazine ''[[Aperture (magazine)|Aperture]]''. In the last two decades of her life, Lange's health was poor. She suffered from gastric problems, including bleeding [[ulcer]]s, as well as [[post-polio syndrome]] — although this renewal of the pain and weakness of polio was not yet recognized by most physicians. She died of [[esophageal cancer]] on October 11, 1965, aged 70.<ref name="profile"/> | ||

Revision as of 20:57, 23 September 2007

| Dorothea Lange | |

Dorothea Lange in 1936; photographer

| |

| Occupation | American photographer, Documentary Photographer Photojournalist |

|---|---|

| Spouse(s) | Maynard Dixon (1920-1935) Paul Schuster Taylor (1935-1965) |

| Children | Daniel and John Dixon |

Dorothea Lange (May 25 1895 – October 11 1965) was an influential American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Dust Bowl photographs, taken throughout the American south and the west, chronicalling the hard scrabble lives of migrant works. Lange's photographs gave a human face to a dark chapter in America history - the Great Depression. Her pictures of mothers and fathers, of the homeless, of those in soup lines, of children in ragged clothing, not only profoundly influenced the development of documentary photography but also of social policies under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal administration. She photographed everyday Americans; their strength and their resolve, and the bonds of family and community that helped them to survive difficult times.

With her second husband, Paul Taylor an expert in farming and migratory labor, she travelled the world contributing, through her work, to the new era of global communications that was burgeoning after World War II and to the developing concept of an international family of man.

Early life and career

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, her birth name was Dorothea Margarette Nutzhorn. After her father's abandonment of the family she and her siblings dropped the patronym Nutzhorn and adopted their mother's maiden name of Lange. Another childhood trauma for Lange was the contraction of polio in 1902, at age seven. Like other polio victims before treatment was available, Lange emerged with a weakened right leg and dropped foot. Although she compensated well for her disability, she always walked with a limp. Lange once commented on her disability saying,

- I was physically disabled, and no one who hasn't lived the life of a semi-cripple knows how much that means. I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, insructed me, helped me, and humuliated me. All those things at once.[1]

Lange learned photography in New York City in a class taught by Clarence H. White of the Photo-Secession group at Columbia University She informally apprenticed herself to several New York photography studios, including that of the famed society photographer Arnold Genthe. In 1918, she moved to San Francisco, where she opened a successful portrait studio. She lived across the bay in Berkeley for the rest of her life. In 1920, she married the noted western painter Maynard Dixon, with whom she had two sons: Daniel, born 1925, and John, born 1928.[2]

Photography and the Great Depression

After the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing depression, Lange finding herself bored with photographing the societal elite, and turned her camera lens to the street. Her first notable picture, taken in 1934, titled White Angel Breadline shows a group of men in a food line near her studio. Her studies of the unemployed and the homeless captured the attention of not only the public but of government officials and led to her employment with the federal Resettlement Administration (RA), later called the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Another person whose interest she captured was Willard Van Dyke, a founding member of the the avant-garde Group f/64, who exhibited her works in his gallery.

In December 1935, she divorced Dixon and married agricultural economist Paul Schuster Taylor, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley.[2] Together, over the next five years, they documented rural poverty including sharecroppers and migrant laborers — Taylor interviewing and gathering economic data, Lange taking photos. Some of her best photographs from this period were compiled in a book by Lange called American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion.

From 1935 to 1939, Lange's work for the RA and FSA brought the plight of the poor and forgotten — particularly, displaced farm families and migrant workers — to public attention. Distributed free to newspapers across the country, her poignant images became icons of the era.

Lange's most well-known picture, titled "Migrant Mother," (1936) shows a weary and worried woman, a pea picker, and her hungry children. The picture resulted in aid to the pea pickers and was used internationally to raise funds for medical supplies. Many years later the identity of the woman, Florence Owens Thompson was discovered, but Lange apparently never knew her name.

In 1960, Lange spoke about her experience taking the photograph:

- I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.

According to Thompson's son, Lange got some details of this story wrong,[3] but the impact of the picture was based on the image showing the inner strength yet desperate need of migrant workers.

Photographing internment camps: World War II

In 1941, Lange was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for excellence in photography. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, she gave up the prestigious award to record the forced evacuation of Japanese-Americans (Nisei) to relocation camps in the American West, on assignment for the War Relocation Authority (WRA). She covered the rounding up of Japanese Americans, their evacuation into temporary assembly centers, and Manzanar, the first of the permanent internment camps. To many observers, her photograph of young Japanese-American girls pledging allegiance to the flag shortly before they were sent to internment camps is a haunting reminder of this policy of detaining people without charging them with any crime simply based on their country of origin and its association through a time of war.

Her images were so politically sensitive when they were taken that the United States Army impounded them and they remained suppressed for many years. In 2006 nearly 800 of Lange's photos were resurrected from the National Archives and are available on the website of the Still Photographs Division, and at the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

End of life and Legacy

On her technique Lange once commented,

- For me documentary photography is less a matter of subject and more a matter of approach. The important thing is not what's photographed, but how.... My own approach is based upon three considerations. First - hands off! Whatever I photograph, I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second - a sense of place. Whatever I photograph, I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third - a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or in the present.[4]

In 1952, Lange co-founded the photographic magazine Aperture. In the last two decades of her life, Lange's health was poor. She suffered from gastric problems, including bleeding ulcers, as well as post-polio syndrome — although this renewal of the pain and weakness of polio was not yet recognized by most physicians. She died of esophageal cancer on October 11, 1965, aged 70.[2]

Lange was survived by her second husband, Paul Taylor, two children, three step-children, and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Notes

- ↑ Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Oliver, Susan (2003-12-07). Profile of Dorothea Lange. Dorothea Lange: Photographer of the People. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ↑ Dunne, Geoffrey, "Photographic license", New Times, 2002.

- ↑ Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davis, Keith F. Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards/Abrams, New York, 1995 ISBN 0-8109-6315-9

- "Dorothea Lange." Contemporary Heroes and Heroines. Book IV. Gale Group, 2000 Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale.

- "Dorothea Lange" Contemporary Women Artists. St. James Press, 1999. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale.

- Dunne, Geoffrey, "Untitled Depression Documentary" 1980

- Gordon, Linda , Dorothea Lange, Encyclopedia of the Depression

- Gordon, Linda, Paul Schuster Taylor, American National Biography

- Gordon, Linda and Gary Okihiro, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

- Meltzer, Meltzer, Dorothea Lange: A Photographer's Life New York, 1978.

External links

- Khasnis, Gridhar. The Hindu. 2006;"Article About Migrant Mother: The True Story". The Hindu. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Dorothea Lange - "A Photographers Journey"". Gendell Gallery. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- Doud, Richard K. AAA. 1964"Dorothea Lange Oral History Interview". Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "'Migrant Mother', an Essay on Liberal Propaganda". Capital Flow Analysis. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Dorothea Lange Collections", Oakland Museum of California. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Gallery of all Lange FSA photographs". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Dorothea Lange- Selection of photographs". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- [1] Civil Control Station, Registration for evacuation and processing. San Francisco, April 1942. War Relocation Authority, Photo By Dorothea Lange,From the National Archive and Records Administration taken for the War Relocation Authority courtesy of the Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley, California. Published in Image and Imagination, Encounters with the Photography of Dorothea Lange, Edited by Ben Clarke, Freedom Voices, San Francisco, 1997

- [2] Pledge of allegiance at Rafael Weill Elementary School a few weeks prior to evacuation, April, 1942. N.A.R.A.; 14GA-78 From the National Archive and Records Administration taken for the War Relocation Authority courtesy of the Bancroft Library. Published in Image and Imagination, Encounters with the Photography of Dorothea Lange, Edited by Ben Clarke, Freedom Voices, San Francisco, 1997

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.