Czechoslovakia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

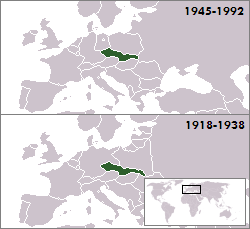

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: Československo, or (increasingly after 1990) in Slovak Česko-Slovensko) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992 (with a government-in-exile during the World War II period). On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, and the Zaolzie region went under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia (1939-1945). De jure Czechoslovakia continued to exist, with the exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, based in London. Following the German invasion of Russia, the USSR recognized the exiled government as well.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers setting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- from 1960 on the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: a federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

Neighbours: West Germany and East Germany, Poland, Soviet Union, Ukraine), Hungary, Romania, and Austria.

Official Names

- 1918–1920: Czecho-Slovak Republic or Czechoslovak Republic (abbreviated RČS); short form Czecho-Slovakia or Czechoslovakia

- 1920–1938 and 1945–1960: Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR); short form Czechoslovakia

- 1938–1939: Czecho-Slovak Republic; Czecho-Slovakia

- 1960–1990: Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR); Czechoslovakia

- April 1990: Czechoslovak Federative Republic (Czech version) and Czecho-Slovak Federative Republic (Slovak version),

- afterwards: Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (ČSFR, with the short forms Československo in Czech and Česko-Slovensko in Slovak)

History

Foundation

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary following the end of World War I. It comprised the present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. On October 16, 1918, Emperor Charles I attempted to rescue the disintegrating Habsburg Monarchy by proposing a federal monarchy, but two days later, US President Woodrow Wilson issued Eleven Points proclaiming an independent state of Czechs and Slovaks. The declaration was drawn up by Thomas Garrigue Masaryk addressed to WIlsona nd the US Government as a response to the foreign policy of Charles I – Czechs and Slovaks wanted more than “autonomy” within the Habsburg Monarchy and demanded complete independence of Czechs and Slovaks in the form of a republic. The Declaration foreshadowed the constitution of the future state, promising broad democratic rights and freedoms, separation of state from church, and expropriation of large tracts of land and abolishment of the class system.

On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár formed the provisional government, while, the Slovak National Committee adopted a proclamation on the right for self-determination of Slovakia and the joint state with Czechs two days later, with Masaryk elected president .

Until the outbreak of World War II, it was a democratic republic, albeit with ethnic tensions stemming from the dissatisfaction of Germans and Slovaks, the second and third largest ethnic groups, respectively, with the political and economic dominance of the Czechs. Moreover, most ethnic Germans and Hungarians never accepted the creation of the new state. These ethnic groups, including Ruthenians and Poles, felt disadvantaged within Czechoslovakia, because the country's political elite introduced a centralized state and was reluctant to safeguard political autonomy for the ethnic groups. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland, fueled the growing unrest among the Non-Czech population.[1]) and also some Slovaks,

World War II

End of the State

Following the German annexation of Austria with the Anschluss, Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia) would be Adolf Hitler's next demand. The Munich Agreement, signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Adolf Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier, deprived Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, which was crucial to Czechoslovakia as most of its elaborate and costly border defences were situated there. Ethnic Germans formed a majority of the region’s population. Many Sudeten Germans rejected affiliation with Czechoslovakia because their right to self-determination pledged by US president Wilson in his Fourteen Points of January 1918 had not been honored by the Czechoslovak government. Wehrmacht troops occupied the Sudetenland in October 1938. Within ten days, 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living in the Sudetenland areas were forced to leave their homes. The greatly weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs.Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected independent and lawyer by training, was appointed president. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without armed action and without Czechoslovakia’s participation in the deal. In November, the First Vienna Award gave Hungary territory in southern Slovakia.

On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Adolf Hitler; the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany, which served Hitler well and provided him with a pretext to declare that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and thus occupation of Bohemia and Moravia would forestall a chaos in Central Europe. The Czechoslovak President described the signing away Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, ruled directly by the German state, for which he had been referred to as traitor of the nation, as follows: “You can withstand Hitler’s yelling, because you are not necessarily a devil for yelling. But Göring, with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prauge to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, who is capable of carrying out his threat, was speaking to me.” The Czechoslovak President was also asked the following by Göring: “You do not want or cannot understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?”

Hácha had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure, in the course of which he collapsed. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that ‘We would have shed a lot of blood.[4] [Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out products for the Third Reich. Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an uprising against their government. German forces crushed this uprising after several weeks of fighting.

A Czechoslovak government-in-exile was established in London by Edvard Beneš, who was recognized as President of Czechoslovakia by the British and other Allied governments and returned to power after Czechoslovakia's liberation in 1945, re-elected to office in 1946. Under the exiled government, Czechoslovak foreign units were being formed by recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens. Military units were formed in Poland, France and Great Britain. Czechoslovakia was swept by massive demonstrations on October 28, 1939, the anniversary of the establishment of the country, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence of Czechoslovakia. Medical student Jan Opletal was killed in the confrontations with the occupants, which was met with further demonstrations. The Nazi Germany responded with terror targeting students, and executed without a trial nine student officials and closed down universities. These brutal reprisals showed that further open encounter with the occupation forces were not possible, and resistance movement shifted to illegal organizations and their links to resistance networks. The goal was to resotre the independent Czechoslovakia.

The resistance movement in Czechoslovakia had three phases: before Heydrich's arrival, Heydrich's rule, and after Heydrich and was sustained by both national and foreign-based representative offices formed in European countries that rejected Nazism. Gradually, these offices oversaw forming of Czechoslovak units abroad. On the home turf, resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which culminated in 1941. Its peak spanned 1939-1941, with the entire nation involved. The first stage did not involve the whole country, and in the third one, many Czechs sympathized with Communism.

the society was split in three streams with respect to their stance on the Nazi occupation: the largest stream consisted of people who did not agree with the occupation but remained passive for various reasons and would swing both ways, those who supported the resistance movement, and, lastly, members of the resistance movement groups and organizations, who were seeking the restoration of the independent Czechoslovak Republic. From the first days of the Protectorate, Jews were being cut off from the society at large as the first step towards the “Final Solution” of the Jewish issue. The widespread arrests severely disrupted illegal resistance movement networks, adn the Czechoslovak Central National Revolutionary Committee was crushed in October 1941. That is why paratroopers were being dispatched into the Protectorate to restore severed radio networks between domestic and foreign resistance movement, restore intelligence networks and carry out acts of sabotage.

Operation Anthropoid

The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination of the top Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the Gestapo (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the key planner in removing all Hitler's opponents, as well as the key planner of the genocide of the Jews. He was involved in most of Hitler's intrigues, and a valued political ally, advisor and friend of the dictator. Due to his abilities and power he was feared by Nazi generals. Thanks to his accomplishment as the liquidator of resistance movements in European countries, Hitler in September 1941 sent him to Prague to make order as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, replacing Konstantin von Neurath whom Hitler considered too moderate. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was of strategic importantance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich did not waste time upon his arrival, starting to hand out death sentences for Czech military officials, resistance movement fighters and political figures the next day following his arrival in Prague.

The exiled military officials started planning an act that would wake up Czechoslovakia from lethargy, as Heydrich, dubbed the “Butcher of Prague”, "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman", exhibited great skill at liquidating Czech resistance movement. At the same time, paratroopers were being chosen in Great Britain based on their conduct, discipline, character and sense of duty, and they were given an option to choose, in front of a committee, whether they want to participate in the resistance movement. Those who said yes were sent to Special Training School in Scotland, where they underwent rigorous training. Among them were six Czechs and one Slovak, who were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them— Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, carried out the act. Heydrich died of complications following surgery.

All hell broke lose in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, with the Gestapo tracking the paratroopers’ contacts thanks to a treason of one of the paratroopers, and eventually discovered their hideaway, the Church of Cyril and Methodius in Prague. Three of the paratroopers died in a shootout in the choir area, trying to buy time for their fellow soldiers so that they could dig out an escape route, but the Gestapo found out and used tear gas and water to chase the remaining four out. However, the four men used their last bullets to take their lives rather than have the Gestapo capture them alive. Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled down, with all adults executed and young children sent to German families for re-education.

Czech resistance movement was virtually paralyzed by the combined actions of the Gestapo and confidantes; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s enforcement of demands for an independent republic following the end of WWII.

End of War

Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of the future restored Czechoslovakia was high ont eh agenda of the two most influential exiled centres, the exiled government in London with E. Benes at the helm and the communist officials in Moscow led by Klement Gottwald. Both centers saw the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation between Czechoslovakia and the USSR as an efficient roadblock in the way of German expansion and the USSR’s mingling into internal affairs of Czechoslovakia.

A meeting was held in Moscow nin March 1943 with the composition of the new Czechoslovak government, with communists to be part of it, on the agenda. On May 1, 1945, an uprising against German occupation broke out in the Czech lands , with Prague hit the worst. With the assistance of the US Army and particularly the Red Army, the war ended in the Czech lands on May 9.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Events Leading to Communist Takeover

After World War II, pre-war Czechoslovakia was reestablished, The Beneš decrees concerned the expropriation of wartime "traitors" and collaborators accused of treason but also all ethnic Germans and Hungarians. They also ordered the removal of citizenship for people of German and Hungarian ethnic origin who decided to acquire the German and Hungarian citizenship during the occupation. (These provisions were cancelled for the Hungarians, but not for the Germans, in 1948). This was then used to confiscate their property and expel around 90% of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia. The people who remained were collectively accused of supporting the (after the Munich Agreement, in December 1938, 97.32% of adult Sudetengermans voted for Nazis in elections). Almost every decree explicitly stated that the sanctions did not apply to anti-fascists although the term Anti-fascist was not explicitly defined. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs, some anti-fascists, but also people required for the post-war reconstruction of the country remained in Czechoslovakia. The Benes Decrees still cause controversy between nationalist groups in Czech Republic, Germany, Austria and Hungary. [2].

Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied by (and in June 1945 formally ceded to) the Soviet Union. In 1946 parliamentary election the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands (the Democratic Party won in Slovakia). In February 1948 the Communists seized power. Although they would maintain the fiction of political pluralism through the existence of the National Front, except for a short period in the late 1960s (the Prague Spring) the country was characterized by the absence of liberal democracy. While its economy remained more advanced than those of its neighbors in Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia grew increasingly economically weak relative to Western Europe. In the religious sphere, atheism was officially promoted and taught. In 1969, Czechoslovakia was turned into a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic. Under the federation, social and economic inequities between the Czech and Slovak halves of the state were largely eliminated. A number of ministries, such as Education, were formally transferred to the two republics. However, the centralized political control by the Communist Party severely limited the effects of federalization.

The 1970s saw the rise of the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, represented (among others) by Václav Havel. The movement sought greater political participation and expression in the face of official disapproval, making itself felt by limits on work activities (up to a ban on any professional employment and refusal of higher education to the dissidents' children), police harassment and even prison time.

Political Situation

The path for the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was paved with the liberation from Nazism by mostly Red Army in May 1945 and the overall social and economic situation in Europe. Marshall’s Plan authored by US State Secretary George Marshall in June 1947 responded to European needs with an offer of financial and material aid and thus stabilization of the region but was turned down by the Soviet Union and, consequently, by its satellites, including Czechoslovakia. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia won the elections one year after the end of WWII, and the resistantce of non-Communist parties to the expanding influence of the Communists boiled down into the coup in February 1948, which sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years.

Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany gripped Czechoslovakia, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forceful collectivization of agricutlrue, censorship, land grabs etc. Economy was synced with five-year plans, in line with the Soviet Union and ‘friendly’ socialist countries. Czechoslovakia’s industry structure was transformed in compliance with Soviet wishes to heavy industry, where the country had negligible tradition.

Year 1960 saw the declaration of the victory of socialism, with small businesses stamped out and the country’s name changed to the Czechoslovak Soicialist Republic. In early 60s, the socialist planning brought about a downturn that spurred an overhaul in the Communist leadership and subsequent economic reforms that grew into the reform of the political system at large. Slovakia’s Alexander Dubcek took over and initiated widespread reforms aimed at ‘socialism with human face’ or Prague Spring, which was crushed under the tanks of the armies of the Warsaw Pact on August 21, 1968.

Prague Spring was replaced by the period of normalization, with political, military and union purges and the repeal of reforms, which thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissidents—a heterogeneous group of people persecuted by the government, produced Charter 77, a document that symbolized opposition with its demand for human rights. The Communists retorted with the Anti-Charter that all artists who wanted to continue working in their field were forced to sign.

In the 80s, the regime began losing the momentum with a stifling economic crisis, and the revolutions in neighboring socialist countries encouraged Czechoslovakia to take steps toward democracy. http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=7664

Velvet Revolution

1989 in the World

The worldwide crumbling of Communism in the world started with Mikhail Gorbatchev’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York where he declared his belief in the right for self-determiantion for all nations, which he confirmned by the unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet roops from Europe and Manchuria and the border with China. Gorbachev continued with the rehabilitation of the victims of Stalin dictatorship from 1930-1950. Hungary allowed founding of political parties other than the leading, Communist, party, while Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc demonstrations and Romania imprisoned journalists who signed an Anticommunist Manifesto and Communist party members who dared criticize Ceausescu for it. Czech writer and dissident Vaclav Havel was handed a 21-month jail term for sedition, and the wave of criticism swept the world. The Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan. Bloodbath occurred in East Berlin and its infamous Berlin Wall. In Poland, a series of strikes forced the government to strike a deal with Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarita movement. Elections in the Soviet Union in March 1989 saw Communist candidates defeated, which spurred calls for the secession of the small Soviet republics from the Soviet Union. One million students in Beijing took to the streets hoping that Gorbachev’s visit to China would be followed by reforms; however, thousands of them were murdered at the Tchien-an-men Square. Gorbachev, visiting East Germany, told East German president Erich Honecker to introduce reforms in response to the latter’s plea with massive anti-government demonstrations, but after his departure, Honecker ordered shooting of demonstrators in Leipzig. Hungarian communists, disgusted with the crimes commited by their own party over the previous years, voted for the dissolution of their own party. In September, all border crossings between East and West Germany were open.

Ceausescu and his wife Elena were charged with geno cide and corruption and executed in a televised process.

November 1989

17. listopadu 1939 28. říjen 1939, první svátek vzniku republiky v době existence protektorátu. Při demonstracích (výslovně zakázaných) bylo v tento den těžce zraněno několik demonstrantů.

Jeden z nich, vysokoškolský student Jan Opletal, zemřel 11. listopadu.

Jeho pohřeb, který se konal 15. listopadu, se stal záminkou pro další vystoupení vysokoškolských studentů proti okupantům. Odehrály se další srážky mezi policií a německými bojůvkami se studenty, kteří strhávali dvojjazyčné nápisy a házeli je do Vltavy.

V reakci na tyto události byly ráno 17.11.1939 přepadeny vysokoškolské koleje a kancléř von Neurath nařídil uzavření vysokých škol na dobu tří let. Bylo popraveno 9 studentských funkcionářů a 1200 náhodně vybraných vysokoškoláků deportováno do koncentračních táborů.

Postiženo bylo 10 vysokých škol, 1223 zaměstnanců a 17556 studentů.

17. listopadu 1989 Padesáté výročí událostí z listopadu 1939.

Komunisté využívali po celou dobu své vlády památky Jana Opletala ve svůj prospěch. V roce 1989 však hrozilo, že oficiální akce dopadne s neúspěchem, který již nebude možno přehlédnout. Proto přišli Svazáci s nabídkou na společné uspořádání akce s Nezávislými studenty.

Podle původních záměrů Nezávislých studentů měl v tento den vyjít pochod od Patologického ústavu na Albertově, tedy z místa, odkud vyšel před 50 lety i pohřeb Jana Opletala. Pokračovat měl přes Karlovo náměstí, Štěpánskou ulicí do Opletalovy ulice a zakončen měl být položením květin v parku před Hlavním nádražím.

Sametová revoluce aneb "Jedenáct dní, které otřásly Československem"

Ještě ráno 17. listopadu 1989 nebyl tento den ničím vyjimečný. Pro normálního člověka normální listopadový pátek. Většinu obyvatelstva čekaly odpoledne nezbytné fronty, spojené s nákupem na víkend. Někteří plánovali odjezd na chatu či chalupu. Bude již třeba zazimovat.

Večer se v zpravodajství Československé televize lidé dozvěděli, že na Národní třídě v Praze musela Veřejná Bezpečnost rozehnat další z demonstrací a obnovit zde pořádek.

V Československu se po roce 1968 demonstrovala, pouze při různých oficiálních příležitostech, jednota lidu s komunistickou stranou. V průběhu 80. let se však v Praze konaly demonstrace komunistickou stranou neorganizované a tudíž nelegální. Většinou u příležitosti výročí 21. srpna 1968 nebo výročí vzniku republiky 28. října 1918. O většině z nich se občané z oficiálních sdělovacích prostředků nedozvěděli. Později maximálně zmínka o ztroskotancích, kteří narušili veřejný pořádek. Problémy existují, ale ty komunistická strana řeší.

Ti, kteří poslouchali západní rozhlasové stanice věděli víc. Věděli, že demonstrace 17.11.1989 byla jiná. Nešlo jen o zásah vodními děly a průběžné zatýkání. Nyní byla použita hrubá síla proti mladým lidem. A snad také jeden z nich zemřel. Informace se rychle rozšířila mezi lidmi.

Večer již nebyl 17. listopad 1989 obyčejným dnem. Ve veřejnosti se cosi hnulo. Snad poslední kapka přetekla a události dostaly rychlý spád. Na konci byly svobodné volby a změna společenského řádu.

17.-18. listopad 1989

Už v øíjnu 1989 informovali pražští funkcionáøi Socialistického svazu mládeže (SSM) mìstký výbor KSÈ v Praze, že na 17. listopadu pøipravují manifestaci èeskoslovenských vysokoškolákù k uctìní památky Jana Palacha. Komunistiètí funkcionáøi nemohli z politických dùvodù manifestaci napovolit, ale také nehodlali pøipustit, aby se z ní stala demonstrace proti režimu. Schválili ji proto (i když nepovolili pùvodnì plánovanou trasu pøes Václavské námìstí), a na 17. listopadu vyhlásili mimoøádnou bezpeènostní akci. Místní správy SNB dostali pøíkaz zajistit klid a poøádek; na schùzce minisra vnitra Kincla s generálním tajemníkem ÚV KSÈ Jakešem se dohodlo, že však nesmí dojít k zásahu.  Nezávislí studenti, kteøí stejnì jako svazáci akci pøipravovali, mìli dvì možnosti. Buï se pøipojit k akci SSM, aby jejich demonstrace byla legální (což by se jistì projevilo na poètu úèastníkù), nebo ji uspoøádat oddìlenì, v tom pøípadì ovšem nelegálnì. Nakonec se rozhodli pro variantu první. Studentská manifestace zaèala projevem Martina Klímy za nezávislé studenty, který prohlásil, že nejde ani tak o boj za svobodu v minulosti, jako o pøítomnost a budoucnost. Jeho vystoupení vzbudilo souhlasný ohlas, narozdíl od následujícícho vystoupení øeèníka za SSM. Poté se až 50 000 úèastníkù (dosud nejvyšší poèet) vydal na Vyšehrad. Na Národní tøídì jim byla cesta pøehrazena policejním kordonem, a asi 2 000 demonstrantù uvízlo mezi dvìma kordony poøádkových sil. Aè se chovali pokojnì (pøesnì podle skanodvaného hesla 'Máme holé ruce'; dívky dávaly pøíslušníkùm bezpeèosti za štíty kvìtiny), byly kolem pùl deváté veèer zatlaèeni smìrem k postranním ulièkám, ve kterých byli mnozí prchající surovì zbiti (nezávislá lékaøská komise pozdìji zjistila, že bylo zranìno 568 lidí). Ve 21:10 byla demonstrace rozehnána; studenti umìleckých škol se rozešli do pražských divadel, kde vyprávìli, co se na Národní tøídì stalo, a žádali herce o podporu. Zaèalo se uvažovat o stávce jak v divadlech, tak na vysokých školách.  Následujícího dne se projevil úèinek událostí 17. listopadu na psychiku obyvatel. Mnozí, i komunisté, byli pohoršeni zpùsobem zásahu poøádkových sil, a lidé se spontánnì zaèali shromažïovat v ulicích. Na shromáždìní v realistickém divadle, kam pøišli srudenti informovat o událostech pøedešlého dne, byla navržena týdenní stávka na podporu studentù, kteøí týdenní stávku již vyhlásili, a jejich sedmi požadavkù (zveøejnit úplné a pravdivé informace ohlednì zásahu, jména odpovìdných osob, jejich vyšetøení a potrestání...). Dále byla navržena dvouhodinová generální stávka na 27. listopad od 12 do 14 hodin. Bìhem tohoto dne se také šíøí zpráva o smrti studenta Martina Šmída. Pøišla s ní již po demonstraci 17. listopadu Drahomíra Dražská a 18. listopadu veèer se pøes Petra Uhla dostala do zpráv (pochopitelnì ne v ÈST, ale na Svobodné Evropì). Psychologický dopad této dezinformace byl významný, hlavnì na mimopražské studenty a obèany vùbec, kteøí v událostech 17. listopadu dosud vidìli jen další ze série demonstrací v Praze.

17.-18. listopad***listopad '89***prosinec '89

Listopad 1989

19. listopadu oznámila ministrynì školství, že se podaøilo najít studenta Martina Šmída, a dementovala tím informaci o jeho smrti. V poledne se v bytì Václava Havla setkali èlenové nezávislých iniciativ. Výsledkem jejich porady je ustanovení Obèanského fóra, které vzniklo v deset hodin veèer v Èinoherním klubu a jehož základní provolání Václav Havel odpoledne sestavil. Obèanské fórum žádá odstoupení nejzkorumpovanìjších politikù, propuštìní politických vìzòù a podporuje avizovanou generální stávku. V Bratislavì tohoto dne vzniká hnutí Veøejnost proti násilí; pøedseda èeské vlády ve 21 hodin v televizi vyzývá ke klidu a podpoøe vedení zemì  Následujícího dne se na vìtšinì pražských vysokých škol podaøilo zahájit stávku. Slovenská, èeská i èeskoslovenská vláda podpoøily policejní zásah na Národní tøídì a prohlásily, že dialog nelze vést v atmosféøe emocí, vášní a protisoialistických vystoupení. Odpoledne se zaplnila námìstí po celé republice, na Václavském námìstí se sešlo pøes 100 000 lidí, v Brnì 40 000...  O den pozdìji, 21. listopadu, se ke stávce pøidaly zbývající školy a na Václavském námìstí se konala první manifestace Obèanského fóra, z Melantrichova balkonu k davùm (shromáždilo se 200 000 lidí) poprvé promluvil Václav Havel. Pøedseda èeskoslovenské vlády Adamec jednal se zástupci veøejnosti (kromì Havla, se kterým jednat odmítl), Milouš Jakeš pak v televizi prohlásil, že KSÈ neustoupí od socialistické cesty rozvoje. Pøíštího dne se opìt na Václavském námìstí konala demonstrace Obèanského fóra, na bratislavském námìstí Slovenského národního povstání se sešlo 100 000 lidí, k nimž promluvil Milan Kòažko a Ján Budaj. Ve stávce už byly školy na celém území Èeskoslovenska. Do Prahy byly povolány Lidové milice, ale vrchní velitel Milouš Jakeš je posléze odvolal.  23. listopadu se uskuteènila dosud nejpoèetnìjší demonstrace na Václavském námìstí a 24. listopadu celý den zasedal ÚV KSÈ. V 19 hodin pak Milouš Jakeš oznámil, že on i celé vedení ÚV dávají své funkce k dispozici. Oslavy ve štábu Obèanského fóra však byly pøedèasné, vìtšina jmen totiž ve vedení strany zùstala. Obèanské fórum to pak oznaèilo za první a ne zcela jasný krok KSÈ. 25. listopadu prezident republiky zastavil stíhání Jána Èarnogurského, Miroslava Kusého, Jiøího Rumla, Petra Uhla a Rudolfa Zemana. Ladislav Adamec rezignoval na post v ÚV KSÈ na protest proti pomalému postupu pøestavby. Na manifestaci Obèanského fóra na Letné se sešlo 800 000 lidí, shromáždìní poprvé vysílala pøímým pøenosem televize. Veèer v ní také poprvé vystoupil Václav Havel. Federální vláda uèinila první ústupek opozici - vyslovila se pro doplnìní dosud èistì komunistického kabinetu o nestraníky i èleny dalších stran.  27. listopadu mezi 12. a 14. hodinou probìhla po celé republice generální stávka s heslem Konec vlády jedné strany, do které se zapojilo 75% obèanù. Obèanské fórum, které za svùj cíl vyhlásilo vypsání svobodných voleb, pak navrhlo její ukonèení a pøechod na stávkovou pohotovost, protože poždavky OF se zaèínaly plnit. 28. listopadu Ladislav Adamec slíbil, že do 3.12. pøipraví zásadní rekonstrukci vlády; 29. listopadu Federální shromáždìní vèetnì témìø kompletního pøedsednictva ÚV KSÈ jednomyslnì zrušilo ústavní èlánek o vedoucí úloze KSÈ ve spoleènosti. Následujícího dne Ministerstvo školství zrušilo výuku marxismu-leninismu na vysokých školách. Tím byly splnìny základní pøedpoklady pro to, aby byli komunisté zbaveni moci.

17.-18. listopad***listopad '89***prosinec '89

Prosinec 1989

3. prosince, kdy Ladislav Adamec pøedstavil novou vládu, se ukázalo, že komunistické vedení ještì nepochopilo, v jaké situaci se nachází. Bylo v ní totiž 15 komunistù, 1 lidovec, 1 socialista a 3 nestraníci. Nejlépe to vystihlo prohlášení Obèanského fóra: 'KSÈ musí vyvodit všechny dùsledky z toho, že ztratila dùvìru veøejnosti a že již nemá v této zemi žádnou vedoucí úlohu. Složení vlády s nadpolovièní vìtšinou komunistù vùbec neodpovídá'. Pokud by tato vláda skuteènì mìla pøevzít moc, vyzvalo by Obèanské fórum k další generální stávce na 11. prosinec. Následujícího dne se konala demonstrace proti složení nové vlády i v ulicích, zatímco herci a studenti pokraèovali ve stávce. Poprvé od 17. listopadu vystoupil v televizi Gustáv Husák.  7.12. rezignoval Ladislav Adamec a navrhl, aby novou vládu sestavil první místopøedseda Marián Èalfa. Obèanské fórum nebylo s Èalfou spokojeno, ale nakonec se s ním v zájmu uklidnìní situace rozhodlo spolupracovat, pokud pøijme jejich návrhy na složení kabinetu. Pøedsednictvo ÚV KSÈ vylouèilo Milouše Jakeše a Miroslava Štìpána ze strany za 'hrubé politické chyby pøi øešení celospoleèenského napìtí, zejména událotí 17. listopadu'. V následujících dnech probíhala mezi politickýcmi reprezentacemi jednání u kulatého stolu o složení nové vlády. Nakonec bude složena z 10 komunistù, 2 socialistù, 2 lidovcù a 7 nestraníkù.  10. prosince ve 13 hodin jmenoval prezident Gustáv Husák novou 'vládu národního porozumnìní' a vzápìtí abdikoval. Na Václavském námìstí byla oznámena kandidatura Václava Havla na post prezidenta a Alexander Dubèek se stal pøedsedou Federálního shromáždìní. Bylo dohodnuto, že 'vláda národního porozumnìní' bude fungova jako prozatimní do vypsání svobodných voleb. 29. prosince byl (ještì stále komunistickým parlamentem) jednohlasnì zvolen Václav Havel prezidentem republiky, na jaøe 1990 se zmìnil oficiální název státu na Èeská a Slovenská federativní republika (ÈSFR) a v èervnu 1990 se konaly první svobodné volby po více než ètyøiceti letech totality. Obèané mìli možnost vybírat si z nìkolika desítek politických objektù; Obèanské fórum sdružující rùznorodé demokratické proudy zvítìzilo s 51% hlasù v Èeské republice, na Slovensku zvítìzilo podobnì koncipované hnutí Veøejnost proti násilí. KSÈ získala 13% hlasù.

VÁCLAV HAVEL

Václav Havel se narodil 5.10. 1936 v Praze. Ponìvadž jeho rodina byla spjatá s èeskou politickou scénou 20.- 40. let, nebylo mu po ukonèení základní školy v roce 1951 komunistickou mocí z kádrových dùvodù dovoleno pokraèovat ve studiu. ì pracoval jako jevištní technik v divadlech ABC a Na zábradlí, v letech 1962-1966 dálkovì vystudoval dramaturgii na Divadelní fakultì AMU.  V 60. letech také vznikly Havlovy nejznámìjší divadelní hry (v rùzných divadelních a literárních periodikách publikoval už od svých 20 let), Zahradní slavnost (1963), Vyrozumnìní (1965) a Ztížená možnost soustøedìní (1968). Po okupaci vojsky Varšavské smlouvy Havel vystupoval proti politické represi pøíznaèné pro období normalizace. Roku 1975 napsal otevøený dopis prezidentu Husákovi, v nìmž poukazoval na problémy ès. spoleènosti, v lednu 1977 se stal zakladatelem a jedním z prvních mluvèí iniciativy Charta 77, kterou podepsalo nìkolik stovek lidí. (celkovì v kriminále strávil témìø 5 let, nìkolikrát byl vzat do vazby a poté propuštìn). V té dobì bylo úøady zakázáno jakékoliv publikování jeho dìl. Se svým dílem ovšem slavil výrazné úspìchy v zahranièí.  Roku 1989 byl opìt zatèen, období od ledna do kvìtna strávil ve vìzení. Po svém propuštìní v èervnu inicioval vznik petice Nìkolik vìt, ke které se postupnì pøipojily desítky tisíc lidí. V øíjnu 1989 byl ještì jednou zatèen, po nìkolika dench byl však propuštìn. V lisotpadu 1989 byl jednou z vùdèích osobností revoluce, 19.11. se podílel na vzniku úvpdního prohlášení Obèanského fóra, jehož èelním pøedstavitelem se stal. Svými postoji v dobì totality si získal postavení morální autority a styl se všeobecnì respektovanou osobností. I proto byl dne 10.12 navržen Obèanským Forem na funkci prezidenta a 29.12. 1989 jednomyslnì zvolen komunistickým parlamentem(!) prezidentem ÈSSR. Slíbil, že republiku dovede k demokratickým volbám, k èemuž v létì 1990 skuteènì došlo.  Aèkoli pùvodnì mìl být prezidentem pouze doèasnì, byl v èervenci 1990 opìt zvolen èeskoslovenským prezidentem. Abdikoval až v létì 1992, aby se nemusel podílet na rozpadu ÈSFR. Po Novém roce byl zvolen prezidentem Èeské republiky, roku 1998 byl zvolen podruhé. Jeho funkèní období tak trvalo témìø 13 let a vypršelo v únoru 2003

ALEXANDER DUBÈEK

Alexander Dubèek se narodil 27.11. 1921 v Uhrovci (okr. Topolèany), ale již ve svých ètyøech letech se s rodièi, èleny družstva Interhelpo, pøestìhoval do SSSR. Žil v kirgyzském Pišperku, od roku 1933 pak v Nižním Novgorodì, kde také vystudoval støední školu. V listopadu 1938 se vrátil na Slovensko. Hned v roce 1939, tedy v 18-ti letech, vstoupil do ilegální Komunistické strany Slovenska a zapojil se do odboje (v nìmž se významnì angažoval jeho otec Štefan). Po svém pøíchodu na Slovensko se vyuèil soustružníkem a pøed Slovenským národním povstáním pracoval jako zamìstnanec Škodových závodù v Dubnici nad Váhom. V roce 1944 se aktivnì zúèastnil Slovenského národního povstání, pøi ústupových bojích byl ranìn. Po skonèení války byl destilérem droždárny v Trenèínì a zároveò se politicky angažoval v KSS.  Roku 1951 už byl vedoucím odboru na ÚV KSS v Bratislavì a poslancem Národního shromáždìní. Mezi léty 1952-1955 studoval právnickou fakultu v Bratislavì, od roku 1955 do roku 1958 pak Vysokou stranickou školu pøi ÚV KSSS v Moskvì. Od roku 1958 pak byl èlenem ÚV KSS i ÚV KSÈ. V roce 1963 se stal èlenem tzv. Kolderovy komise pro vyšetøování událostí z 50. let, od roku 1963 byl 1. tajemníkem ÚV KSÈ.  V 60. letech byl jedním z hlavních pøedstavitelù reformního proudu komunistù, vùdèí osobností Pražského jara '68 a tìšil se obrovské popularitì doma i v zahranièí. Usiloval o humanizaci a demokratizaci socialistického zøízení, ale pøi zachování jeho sociálnì ekonomické podstaty. Svùj program se marnì snažil obhájit pøed politiky SSSR i vìtšiny dalších státù Varšavské smlouvy, v srpnu 1968 vedl delegaci KSÈ na jednáních pøedstavitelù komunistických stran zemí sovìtského bloku v Moskvì.  Po sovìtské invazi, kterou s ostatními èleny pøedsednictva ÚV KSÈ odsoudil jako okupaci, byl odvleèen do SSSR, kde po úèasti na jednáních mezi èeskoslovenskou a sovìtskou reprezentací 26.8. 1968 pod nátlakem spolupodepsal tzv. Moskevský protokol o doèasném pobytu vojsk Varšavské smlouvy na našem území a normalizaci pomìrù v Èeskolovensku. Poté byl postupnì odstaven ze všech politických funkcí. V dubnu 1969 byl nucen odstoupit z funkce prvního tajmeníka ÚV KSÈ, poté byl zbaven funkcí v ÚV KSÈ, odklizen jako velvyslanec do Turecka a v létì 1970 vylouèen z KSÈ a prohlášen za èelního pøedstavitele pravicové kontrarevoluce.  Od roku 1970 byl technicko-hospodáøským pracovníkem Západoslovenských lesù, od roku 1985 v dùchodì. V sedmdesátých a osmdesátých letech udržoval styky s opozièním hnutím a opakovanì vystupoval s kritikou režimu. Po zahájení sovìtské pìrestrojky se snažil navázat kontakt s M. Gorbaèovem. Celkovì se z nìho v tomto období spíše než reformní komunista stal demokratický socialista po vzoru západoevropských sociálních demokracií.  V listopadu 1989 opìt vstoupil do politického života, podpoøil OF a pronesl nìkolik projevù, od 28.12. 1989 byl poslancem Snìmovny národù Federálního shromáždìní (SN FS) a jeho pøedsedou (do èervna 1992). Vstoupil do Sociálnì demokratické strany na Slovensku, od bøezna 1992 byl jejím pøedsedou. Podnikl øadu zahranièních cest a pøevzal mnohá vyznamenání, ze strany pravice byl však napadán kvùli své komunistické minulosti. 1.9. 1992 mìl vážnou dopravní nehodu (viníkem byl uznán jeho øidiè, který za špatného poèasí nepøizpùsobil jízdu stavu vozovky, nicménì sám vyvázl jen s lehèím zranìním hlavy), a na následky svého úrazu 7.11. 1992 v pražské nemocnici na Homolce zemøel.

After 1989

http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_11.php

ROLE OF STUDENTS IN REVOLUTION; ARTISTS, OBCANSKE FORUM, HAVEL

In 1989, the country became democratic again through the Velvet Revolution. In 1992 the growing nationalist tensions led to dissolution of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as of January 1, 1993.

Government

Heads of state

- List of Presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of Prime Ministers of Czechoslovakia

International agreements and membership

After WWII, active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

Administrative divisions

Main article: Administrative divisions of Czechoslovakia

- 1918–1923: different systems on former Austrian territory (Bohemia, Moravia, small part of Silesia) and on former Hungarian territory (Slovakia and Ruthenia): 3 lands [země] (also called district units [obvody]) Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia + 21 counties [župy] in today's Slovakia + 2? counties in today's Ruthenia; both lands and counties were divided in districts [okresy]

- 1923–1927: like above, except that the above counties were replaced by 6 (grand) counties [(veľ)župy] in today's Slovakia and 1 (grand) county in today's Ruthenia, and the number and frontiers of the okresy were changed on these 2 territories

- 1928–1938: 4 lands [in Czech: země / in Slovak: krajiny]: Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia; divided in districts [okresy]

- late 1938–March 1939: like above, but Slovakia and Ruthenia were promoted to "autonomous lands"

- 1945–1948: like 1928–1938, except that Ruthenia became part of the Soviet Union

- 1949–1960: 19 regions [kraje] divided in 270 districts [okresy]

- 1960–1992: 10 regions [kraje], Prague, and (since 1970) Bratislava; divided in 109–114 districts (okresy]); the kraje were abolished temporarily in Slovakia in 1969–1970 and for many functions since 1991 in Czechoslovakia; in addition, the two republics Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic were established in 1969 (without the word Socialist since 1990)

Politics

GOTTWALD, HUSAK, DUBCEK

After WWII, monopoly on politics held by Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Gustáv Husák elected first secretary of KSC in 1969 (changed to general secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to KSC. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, grouped under umbrella of the National Front. Human rights activists and religious activists severely repressed.

Constitutional development

Czechoslovakia had the following constitutions throughout its history (1918 – 1992):

- Temporary Constitution of November 14 1918 [democratic], see: Czechoslovakia: 1918 - 1938

- The 1920 Constitution (The Constitutional Document of the Czechoslovak Republic) [democratic, in force till 1948, several amendments], see: Czechoslovakia: 1918 - 1938

- The Communist 1948 Ninth-of-May Constitution

- The Communist 1960 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic with major amendments in 1968 (Constitutional Law of Federation), 1971, 1975, 1978, and in 1989 (at which point the leading role of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was abolished). It was amended several more times during 1990-1992 (e. g. 1990, name change to Czecho-Slovakia, 1991 incorporation of the human rights charter)

Economy

After WWII, economy centrally planned with command links controlled by communist party, similar to Soviet Union. Large metallurgical industry but dependent on imports for iron and nonferrous ores.

- Industry: Extractive and manufacturing industries dominated sector. Major branches included machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. Industry wasteful of energy, materials, and labor and slow to upgrade technology, but country source of high-quality machinery and arms for other communist countries.

- Agriculture: Minor sector but supplied bulk of food needs. Dependent on large imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production constrained by shortage of feed, but high per capita consumption of meat.

- Foreign Trade: Exports estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985, of which 55 % machinery, 14 % fuels and materials, 16 % manufactured consumer goods. Imports at estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, of which 41 % fuels and materials, 33 % machinery, 12 % agricultural and forestry products other. In 1986, about 80 % of foreign trade with communist countries.

- Exchange Rate: Official, or commercial, rate Kcs 5.4 per US$1 in 1987; tourist, or noncommercial, rate Kcs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market was around Kcs 30 per US$1, and this rate became the official one once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

- Fiscal Year: Calendar year.

- Fiscal Policy: State almost exclusive owner of means of production. Revenues from state enterprises primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. Large budget expenditures on social programs, subsidies, and investments. Budget usually balanced or small surplus.

After WWII, country energy short, relying on imported crude oil and natural gas from Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints a major factor in 1980s.

Population and ethnic groups

Czechoslovakia's ethnic composition in 1987 offered a stark contrast to that of the First Republic (see History). The Sudeten Germans that made up the majority of the population in border regions were forcibly expelled after World War II, and Carpatho-Ukraine (poor and overwhelmingly Ukrainian and Hungarian) had been ceded to the Soviet Union following World War II. Czechs and Slovaks, about two-thirds of the First Republic's population in 1930, represented about 94 % of the population by 1950.

The aspirations of ethnic minorities had been the pivot of the First Republic's politics. This was no longer the case in the 1980s. Nevertheless, ethnicity continued to be a pervasive issue and an integral part of Czechoslovak life. Although the country's ethnic composition had been simplified, the division between Czechs and Slovaks remained; each group had a distinct history and divergent aspirations.

From 1950 through 1983, the Slovak share of the total population increased steadily. The Czech population as a portion of the total declined by about 4 %, while the Slovak population increased by slightly more than that. The actual numbers did not imperil a Czech majority; in 1983 there were still more than two Czechs for every Slovak. In the mid-1980s, the respective fertility rates were fairly close, but the Slovak fertility rate was declining more slowly.

From creation to dissolution — overview

|

Czechoslovakia (or Czecho-Slovakia) | 1918 - 1939; 1945 - 1992 |

|||||||

|

Austria-Hungary (Bohemia, Moravia, a part of Silesia, northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia) |

Czechoslovak Republic |

Sudetenland + other German territories "Upper Hungary" territories of Hungary |

Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) |

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) |

Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) |

Czech Republic Slovakia |

|

|

Czecho-Slovak Republic (ČSR) incl. autonomous Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine (1938-1939) |

Protectorate WWII Slovak Republic |

||||||

|

(further) "Upper Hungary" of Hungary |

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine |

|||||

|

German occupation |

Communist era |

||||||

|

govern. in exile |

|||||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Playing the blame game, Prague Post, July 6th, 2005

- ↑ http://www.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11num1_2/special/rupnik.html

External links

- Orders and Medals of Czechoslovakia including Order of the White Lion (in English and Czech)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.