Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Carl Wilhelm Scheele" - New World

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Unlike scientists such as [[Antoine Lavoisier]] and [[Isaac Newton]] who were more widely recognized, Scheele had a humble position in a small town, and yet he was still able to make many scientific discoveries. He preferred his small dwelling to the grandeur of an extravagant house. Scheele made many discoveries in [[chemistry]] before others who are generally given the credit. One of Scheele's most famous discoveries was [[oxygen]] produced as a by-product in a number of experiments in which he heated chemicals during 1771-1772. Scheele, though, was not the one to name or define oxygen; that job would later be bestowed upon [[Antoine Lavoisier]]. | Unlike scientists such as [[Antoine Lavoisier]] and [[Isaac Newton]] who were more widely recognized, Scheele had a humble position in a small town, and yet he was still able to make many scientific discoveries. He preferred his small dwelling to the grandeur of an extravagant house. Scheele made many discoveries in [[chemistry]] before others who are generally given the credit. One of Scheele's most famous discoveries was [[oxygen]] produced as a by-product in a number of experiments in which he heated chemicals during 1771-1772. Scheele, though, was not the one to name or define oxygen; that job would later be bestowed upon [[Antoine Lavoisier]]. | ||

| − | His studies led him to the discovery in 1772-1773 that air was a mixture of [[oxygen]] and [[nitrogen]]. He published this and other discoveries in his only book, ''Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer'' (''Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire'') in 1777, losing some fame to [[Joseph Priestley]], who independently discovered oxygen in 1774. In his book, he also distinguished [[heat transfer]] by [[thermal radiation]] from that by [[convection]] or [[heat conduction|conduction]]. | + | His studies led him to the discovery in 1772-1773 that air was a mixture of [[oxygen]] and [[nitrogen]]. He published this and other discoveries in his only book, ''Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer'' (''Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire'') in 1777, losing some fame to [[Joseph Priestley]], who independently discovered oxygen in 1774. In his book, he also distinguished [[heat transfer]] by [[thermal radiation]] from that by [[convection]] or [[heat conduction|conduction]]. |

| − | + | Scheele's study of "fire air" [[oxygen]] was sparked by a complaint by [[Torbern Olof Bergman]]. [[Bergman]] informed Scheele that the saltpeter he purchased from Scheele's employer produced red vapors when it came into contact with acid. Scheele's quick explanation for the vapors led Bergman to suggest that Scheele analyze the properties of [[manganese dioxide]]. It was through his studies with manganese dioxide that Scheele developed his concept of "fire air." He ultimately obtained oxygen by heating [[mercuric oxide]], [[silver carbonate]], [[magnesium nitrate]], and [[saltpeter]]. Scheele wrote about his findings to [[Lavoisier]] who was able to grasp the significance of the results. | |

| − | + | In addition to his joint recognition for the discovery of oxygen, Scheele is argued to have been the first to discover other chemical elements such as [[barium]] (1774), [[manganese]] (1774), [[molybdenum]] (1778), and [[tungsten]] (1781), as well as several chemical compounds, including [[citric acid]], [[glycerol]], [[hydrogen cyanide]] (also known, in aqueous solution, as prussic acid), [[hydrogen fluoride]], and [[hydrogen sulfide]]. In addition, he discovered a process similar to [[pasteurization]], along with a means of mass-producing [[phosphorus]] (1769), leading Sweden to become one of the world's leading producers of matches. | |

| + | Scheele made one other very important scientific discovery in 1774, arguably more revolutionary than his isolation of [[oxygen]]. He identified [[lime]], [[silica]], and [[iron]], in a specimen of [[pyrolusite]] given to him by his friend, [[Johann Gottlieb Gahn]], but could not identify an additional component. When he treated the pyrolusite with [[hydrochloric acid]] over a warm sand bath, a yellow-green gas with a strong odor was produced. He found that the gas sank to the bottom of an open bottle and was denser than ordinary air. He also noted that the gas was not soluble in water. It turned corks a yellow color and removed all color from wet, blue litmus paper and some flowers. He called this gas with bleaching abilities, "dephlogisticated acid of salt." Eventually, [[Sir Humphrey Davy]] named the gas [[chlorine]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Scheele and the phlogiston theory== | |

| − | + | By the time he was a teenager, Scheele had learned the dominant theory on gases in the 1770s, the [[phlogiston]] theory. Phlogiston, classified as "matter of fire" stated that any material that was able to burn would release phlogiston during combustion, and would stop burning when all the phlogiston had been released. When Scheele discovered [[oxygen]] he called it "fire air" because it supported combustion, but he explained oxygen using phlogistical terms because he did not believe that his discovery disproved the phlogiston theory. | |

| − | + | Historians of science no longer question the role of Carl Scheele in the overturning of the [[phlogiston]] theory. It is generally accepted that he was the first to discover oxygen, among a number of prominent scientists—namely, his adversaries [[Antoine Lavoisier]], [[Joseph Black]], and [[Joseph Priestley]]. In fact, it was determined that Scheele made the discovery three years prior to Joseph Priestley and at least several before [[Lavoisier]]. Joseph Priestley relied heavily on Scheele's work, perhaps so much so that he would not have made the discovery of [[oxygen]] on his own. Correspondence between Lavoisier and Scheele indicate that Scheele achieved interesting results without the advanced laboratory equipment that Lavoisier was accustomed to. Through the studies of Lavoisier, Joseph Priestley, Scheele, and others, [[chemistry]] was made a standardized field with consistent procedures. Although Scheele was unable to grsp the significance of his discovery of oxygen, his work was essential for the invalidation of the long-held theory of phlogiston. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 08:28, 4 August 2007

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (December 9,1742 - May 21, 1786) a German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist, born in Stralsund, Western Pomerania, Germany (at the time under Swedish rule), was the discoverer of many chemical substances, most notably discovering oxygen before Joseph Priestley and chlorine before Humphry Davy.

Biography

Scheele was born in Stralsund, Sweden. He was one of eleven children of a merchant, Joachim Christian Scheele. At age 14, he adopted the vocation of a pharmacist in the establishment of Martin Anders Bauch of Gottenburg. His brother had also worked in for Bauer but died three years before Scheele began his apprentiship. Scheele served for the first six years as a pupil, and three additional years as an assistant. During this period, Scheele availed himself of Bauer's fine library, and by study and practice acheived an expert knowledge of the chemistry of his day. It is said that he studied at the pharmacy after hours, and while conducting experiments late one evening, he triggered an explosion that shook the house and disturbed its occupants. Scheele was told to look for work elsewhere. He then was hired as an apothecary's clerk in Kalstom's establishment in Malmö, where he remained for two years. Then Scheele worked as a pharmacist in the establishment of Scharenberg in [[Stockholm]. At this time, he is said to have submitted a memoir on the discovery of tartaric acid, but it was rejected by the Swedish Acacemy of Sciences, Scheele not being well known at the time. This is said to have discouraged Scheele and made him reticent to contact those who would have most appreciated his work. After spending six years in Stockholm, Scheele transferred to the shop of one Look in Uppsala 1773. It was during this time that he is said to have met the famous Swedish chemist Torbern Olof Bergman. As the story goes, Scheele's employer brought Bergman to the pharmacy to consult Scheele on a matter that had been mystifying him. Sheele offered a clear explanation, as well as in other ways demonstrating a depth of understanding of chemical phenomena of all kinds. Bergman was instrumental in bringing Scheele's accomplishments to the scientific community, and in getting his work published. Scheele thus began to establish an international reputation, and corresponded with the likes of Henry Cavendish of Britain and Antoine Lavoisier of France.

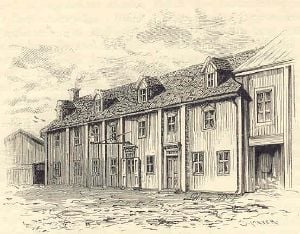

Later years In 1775, Scheele hoped to purchase a pharmacy so that he could work independently. His first attempt was unsuccessful, and led to many invitations to do research and teach in a variety of European capitals. Scheele turned these offers down, preferring to remain in a profession he knew well and that provided sufficiently for his expenses. After a year's delay, he purchased a shop in Koping from Sara Margaretha Sonneman, who had inherited it from her late husband, Hinrich Pascher Pohls. Scheele found that the establishment was saddled with debt, which he was only able to pay off by dilligent attention to his business affairs over a number of years. During this time, he and Pohls's widow kept house together for the sake of economy. He eventually married her, only two days before his death. Scheele managed to retire the entire debt of his new business, and was able to build himself a new home an laboratory. One of his sisters came to assist Sheele in managing the pharmacy and household. Thus they were able to live fairly comfortably for Scheele's remaining years.

During the last decade of his life, he was often visited by scientists who tried to probe his fertile mind. Scheele preferred to entertain in his laboratory or at his pharmacy, and traveled little.

Scheele suffered from gout, and a number of other ailments, including rheumatism. His symptoms intensified toward the final months of his life, although he continued his research until a complete physical breakdown prevented him from going further. His illness was probably brought on by his constant exposure to the poisonous compounds that his experimentation brought him into contact. He died on ________, 1786.

Accomplishments

Unlike scientists such as Antoine Lavoisier and Isaac Newton who were more widely recognized, Scheele had a humble position in a small town, and yet he was still able to make many scientific discoveries. He preferred his small dwelling to the grandeur of an extravagant house. Scheele made many discoveries in chemistry before others who are generally given the credit. One of Scheele's most famous discoveries was oxygen produced as a by-product in a number of experiments in which he heated chemicals during 1771-1772. Scheele, though, was not the one to name or define oxygen; that job would later be bestowed upon Antoine Lavoisier.

His studies led him to the discovery in 1772-1773 that air was a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen. He published this and other discoveries in his only book, Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer (Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire) in 1777, losing some fame to Joseph Priestley, who independently discovered oxygen in 1774. In his book, he also distinguished heat transfer by thermal radiation from that by convection or conduction.

Scheele's study of "fire air" oxygen was sparked by a complaint by Torbern Olof Bergman. Bergman informed Scheele that the saltpeter he purchased from Scheele's employer produced red vapors when it came into contact with acid. Scheele's quick explanation for the vapors led Bergman to suggest that Scheele analyze the properties of manganese dioxide. It was through his studies with manganese dioxide that Scheele developed his concept of "fire air." He ultimately obtained oxygen by heating mercuric oxide, silver carbonate, magnesium nitrate, and saltpeter. Scheele wrote about his findings to Lavoisier who was able to grasp the significance of the results.

In addition to his joint recognition for the discovery of oxygen, Scheele is argued to have been the first to discover other chemical elements such as barium (1774), manganese (1774), molybdenum (1778), and tungsten (1781), as well as several chemical compounds, including citric acid, glycerol, hydrogen cyanide (also known, in aqueous solution, as prussic acid), hydrogen fluoride, and hydrogen sulfide. In addition, he discovered a process similar to pasteurization, along with a means of mass-producing phosphorus (1769), leading Sweden to become one of the world's leading producers of matches.

Scheele made one other very important scientific discovery in 1774, arguably more revolutionary than his isolation of oxygen. He identified lime, silica, and iron, in a specimen of pyrolusite given to him by his friend, Johann Gottlieb Gahn, but could not identify an additional component. When he treated the pyrolusite with hydrochloric acid over a warm sand bath, a yellow-green gas with a strong odor was produced. He found that the gas sank to the bottom of an open bottle and was denser than ordinary air. He also noted that the gas was not soluble in water. It turned corks a yellow color and removed all color from wet, blue litmus paper and some flowers. He called this gas with bleaching abilities, "dephlogisticated acid of salt." Eventually, Sir Humphrey Davy named the gas chlorine.

Scheele and the phlogiston theory

By the time he was a teenager, Scheele had learned the dominant theory on gases in the 1770s, the phlogiston theory. Phlogiston, classified as "matter of fire" stated that any material that was able to burn would release phlogiston during combustion, and would stop burning when all the phlogiston had been released. When Scheele discovered oxygen he called it "fire air" because it supported combustion, but he explained oxygen using phlogistical terms because he did not believe that his discovery disproved the phlogiston theory.

Historians of science no longer question the role of Carl Scheele in the overturning of the phlogiston theory. It is generally accepted that he was the first to discover oxygen, among a number of prominent scientists—namely, his adversaries Antoine Lavoisier, Joseph Black, and Joseph Priestley. In fact, it was determined that Scheele made the discovery three years prior to Joseph Priestley and at least several before Lavoisier. Joseph Priestley relied heavily on Scheele's work, perhaps so much so that he would not have made the discovery of oxygen on his own. Correspondence between Lavoisier and Scheele indicate that Scheele achieved interesting results without the advanced laboratory equipment that Lavoisier was accustomed to. Through the studies of Lavoisier, Joseph Priestley, Scheele, and others, chemistry was made a standardized field with consistent procedures. Although Scheele was unable to grsp the significance of his discovery of oxygen, his work was essential for the invalidation of the long-held theory of phlogiston.

See also

- Antoine Lavoisier

- Humphry Davy

- Joseph Priestley

- Oxygen

- Scheelite

- Scheele's Green

- Pharmacist

- Pharmacy

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbot, David. (1983). Biographical Dictionary of Scientists: Chemists. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 126-127.

- Bell, Madison S. (2005). Lavoisier in the Year One. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Cardwell, D.S.L. (1971). From Watt to Clausius: The Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Heinemann: London, 60-61. ISBN 0-435-54150-1.

- Dobbin, L. (trans.) (1931). Collected Papers of Carl Wilhelm Scheele.

- Farber, Eduard ed. (1961). Great Chemists. New York: Interscience Publishers, 255-261.

- Greenberg, Arthur. (2000). A Chemical History Tour: Picturing Chemistry from Alchemy to Modern Molecular Science. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 135-137.

- Greenberg, Arthur. (2003). The Art of Chemistry: Myths, Medicines and Materials. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 161-166.

- Schofield, Robert E (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773-1804. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Shectman (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- Sootin, Harry (1960). 12 Pioneers of Science. New York: Vanguard Press.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.