Bragi

Bragi is the god of poetry in Norse mythology.

Bragi in a Norse Context

As mentioned above, Bragi is a Norse deity, a designation that signifies his membership in a complex of religious, mythological and cosmological beliefs shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[1] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Bragi is described in some mythic accounts (especially the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson) as a god of skalds (Nordic poets) whose father was Odin and who, resultantly, was one of the Aesir. However, other traditions (discussed below) create the strong implication that Bragi was, in fact, a euhemerized version of a popular eight/ninth century poet.

Characteristics and Mythic Representations

Bragi is generally associated with bragr, the Norse word for poetry. The name of the god may have been derived from bragr, or the term bragr may have been formed to describe 'what Bragi does.'

Given that the majority of descriptions of the deity can be found in the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson, it presents the most logical departure point for a characterization. To begin, Snorri (in the Gylfaginning) writes:

- One is called Bragi: he is renowned for wisdom, and most of all for fluency of speech and skill with words. He knows most of skaldship, and after him skaldship is called bragr, and from his name that one is called bragr-man or -woman, who possesses eloquence surpassing others, of women or of men. His wife is Iðunn.[3]

Refining this characterization in the Skáldskaparmál (a guide for aspiring poets (skalds)), Snorri writes:

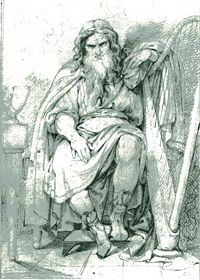

- How should one periphrase Bragi? By calling him husband of Iðunn, first maker of poetry, and the long-bearded god (after his name, a man who has a great beard is called Beard-Bragi), and son of Odin.[4]

Though this verse (and a few others within the Prose Edda) testify that Bragi is Odin's son, it is not an attribution that is borne out through the remainder of the literature.

In that poem Bragi at first forbids Loki to enter the hall but is overruled by Odin. Loki then gives a greeting to all gods and goddesses who are in the hall save to Bragi. Bragi generously offers his sword, horse, and an arm ring as peace gift but Loki only responds by accusing Bragi of cowardice, of being the most afraid to fight of any of the Æsir and Elves within the hall. Bragi responds that if they were outside the hall, he would have Loki's head, but Loki only repeats the accusation. When Bragi's wife Iðunn attempts to calm Bragi, Loki accuses her of embracing her brother's slayer, a reference to matters that have not survived. Perhaps Bragi had slain Iðunn's brother or perhaps the reference is to something else entirely.

A passage in the eddic poem Sigrdrífumál describes runes being graven on the sun, on the ear of one of the sun-horses and on the hoofs of the other, on Sleipnir's teeth, on bear's paw, on eagle's beak, on wolf's claw, and on several other things including on Bragi's tongue. Then the runes are shaved off and the shavings are mixed with mead and sent abroad so that Æsir have some, Elves have some, Vanir have some, and Men have some, these being beech runes and birth runes, ale runes, and magic runes. The meaning of this is obscure.

<why is this so important? tie it to the mention in the opener of the role of poetry in Norse society> The first part of Snorri Sturluson's Skáldskaparmál is a dialogue between Ægir and Bragi about the nature of poetry, particularly skaldic poetry. Bragi tells the origin of the mead of poetry from the blood of Kvasir and how Odin obtained this mead. He then goes on to discuss various poetic metaphors known as kennings.

<False... correct this misimpression> Snorri Sturluson clearly distinguishes the god Bragi from the mortal skald Bragi Boddason whom he often mentions separately. Bragi Boddason is discussed below. The appearance of Bragi in the Lokasenna indicates that if these two Bragis were originally the same, they have become separated for that author also, or that chronology has become very muddled and Bragi Boddason has been relocated to mythological time. Compare the appearance of the Welsh Taliesin in the second branch of the Mabinogi. Legendary chronology sometimes does become muddled. Whether Bragi the god originally arose as a deified version of Bragi Boddason was much debated in the 19th century, especially by the German scholars Eugen Mogk and Sophus Bugge. The debate remains undecided.

<bragi's role in welcoming new additions to Odin's hall (tie above)> In the poem Eiríksmál Odin, in Valhalla, hears the coming of the dead Norwegian king Eirík Bloodaxe and his host, and bids the heroes Sigmund and Sinfjötli rise to greet him. Bragi is then mentioned, questioning how Odin knows that it is Eirik and why Odin has let such a king die. In the poem Hákonarmál, Hákon the Good is taken to Valhalla by the valkyrie Göndul and Odin sends Hermóðr and Bragi to greet him. In these poems Bragi could be either a god or a dead hero in Valhalla. Attempting to decide is further confused because Hermóðr also seems to be sometimes the name of a god and sometimes the name of a hero. That Bragi was also the first to speak to Loki in the Lokasenna as Loki attempted to enter the hall might be a parallel. It might have been useful and customary that a man of great eloquence and versed in poetry should greet those entering a hall.

Other Spellings

- Scandinavian form: Brage

- German form: Brego

Modern invention

- Bragi's mother was Frigg.

- Bragi was son of Odin by the giantess Gunnlöd.

- Bragi was generally conceived to have runes permanently carved into his tongue.

- Bragi was told to let the runes out like butterflies at banquets of the gods and in Valhalla in the form of poetry.

- Bragi had runes carved on his tongue by his wife Iðunn, the inventor of runes. (This is an invention of Barbara Walker, author of The Crone.)

- Bragi was responsible for doling out the mead of poetry.

- Bragi customarily greeted new arrivals to Valhalla. (In fact this occurs only in the poem Eiríksmál.)

Some of the above are reasonable as modern literary invention in retellings or as scholarly speculation and may even have been what the ancient Norse believed for all that is known, but they are not found in surviving texts.

A. & E. Keary in the back matter to their Heroes of Asgard (published in 1891), provides the following on Bragi's name:

From braga, "to shine;" or bragga, "to adorn." Bragr, which in Norse signifies "poetry," has become in English "to brag," and a poet "a braggart." From Bragi's bumper, the Bragafull, comes our word "bragget," and probably, also, the verb "to brew;" Norse, brugga.

A relation to braga 'to shine' is not generally accepted, must less to bragga or brugga. English brag might indeed be from Old Norse braugr, discussed above, if not from braying of a trumpet. But English brew is certainly unrelated to Bragi, though brew is related to Old Norse brugga.

Bragi Boddason

- Main article: Bragi Boddason

In his Edda Snorri Sturluson quotes many stanzas attributed to Bragi Boddason the old (Bragi Boddason inn gamli), a court poet who served several Swedish kings, Ragnar Lodbrok, Östen Beli and Björn at Hauge who reigned in the first half of the ninth century. This Bragi was reckoned as the first skaldic poet, and was certainly the earliest skaldic poet then remembered by name whose verse survived in memory.

Snorri especially quotes passages from Bragi's Ragnarsdrápa, a poem supposedly composed in honor of the famous legendary Viking Ragnar Lodbrók ('Hairy-breeches') describing the images on a decorated shield which Ragnar had given to Bragi. The images included Thor's fishing for Jörmungandr, Gefjun's ploughing of Zealand from the soil of Sweden, the attack of Hamdir and Sorli against King Jörmunrekk, and the never-ending battle between Hedin and Högni.

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning (XXVI), (Brodeur 39).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (X), (Brodeur 113).

Bibliography

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.