Bone

Bone, also called osseous tissue, (Latin: "os") is a type of hard endoskeletal connective tissue found in many vertebrate animals. Bones support body structures, protect internal organs, and (in conjunction with muscles) facilitate movement; are also involved with cell formation, calcium metabolism, and mineral storage. The bones of an animal are, collectively, known as the skeleton. Bone has a different composition than cartilage, and both are derived from mesoderm. In common parlance, cartilage can also be called "bone", certainly when referring to animals that only have cartilage as hard connective tissue, such as cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) like sharks. True bone is present in bony fish (Osteichthyes) and all tetrapods.

There are several evolutionary alternatives to bone. These evolutionary solutions are not completely functionally analogous to bone.

- Exoskeletal protection is offered by shells, carapaces (consisting of calcium compounds or silica) and chitinous exoskelotons.

- A true endoskeleton (that is, protective tissue derived from mesoderm) is also present in Echinoderms. Porifera (sponges) possess simple endoskeletons that consist of calcareous or siliceous spicules and a spongin fiber network.

Bones and skeletons are studied in osteology. Bones can be prepared for study by several methods, such as maceration. Maceration is done by boiling fleshed bone with dish detergent and a little bleach until all large particles are off. The bones are then cleaned by hand, usually with a toothbrush and a degreaser.

Functions

Long bones can be connected to skeletal muscles via tendons. Bones connect at joints by ligaments. The interaction between bone and muscle is studied in biomechanics.

Structure

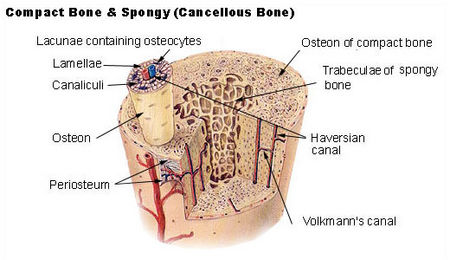

Bone is a relatively hard and lightweight composite material, formed mostly of calcium phosphate in the chemical arrangement termed calcium hydroxyapatite. It has relatively high compressive strength but poor tensile strength. While bone is essentially brittle, it does have a degree of significant elasticity contributed by its organic components (chiefly collagen). Bone has an internal mesh-like structure, the density of which may vary at different points.

Bone can be either compact or cancellous (spongy). Cortical (outer layer) bone is compact; the two terms are often used interchangeably. Cortical bone makes up a large portion of skeletal mass; but, because of its density, it has a low surface area. Cancellous bone is trabecular (has an open, meshwork or honeycomb-like structure). It has a relatively high surface area, but forms a smaller portion of the skeleton.

Bone can also be either woven or lamellar. Woven bone is put down rapidly during growth or repair. It is so called because its fibres are aligned at random, and as a result has low strength. In contrast lamellar bone has parallel fibres and is much stronger. Woven bone is often replaced by lamellar bone as growth continues.

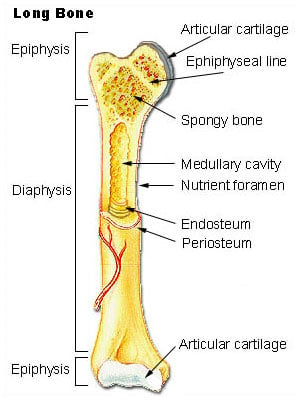

Long bones are tubular in structure (e.g. the tibia). The central shaft of a long bone is called the diaphysis, and has a hollow middle—the medullar cavity filled with bone marrow. Surrounding the medullar cavity is a thin layer of cancellous bone that also contains marrow. The extremities of the bone are called the epiphyses and are mostly cancellous bone covered by a relatively thin layer of compact bone. In children, long bones are filled with red marrow, which is gradually replaced with yellow marrow as the child ages.

Short bones (e.g. finger bones) have a similar structure to long bones, except that they have no medullar cavity.

Flat bones (e.g. the skull and ribs) consist of two layers of compact bone with a zone of cancellous bone sandwiched between them.

Irregular bones are bones which do not conform to any of the previous forms (e.g. vertebrae).

All bones consist of living cells embedded in a mineralised organic matrix that makes up the main bone material.

Cells

Bone cells include osteoblasts, so called Bone Lining Cells, osteocytes and osteoclasts. Osteoblasts are typically viewed as bone forming cells. They are located near to the surface of bone and their functions are to make osteoid and manufacture hormones such as prostaglandin which act on bone itself. Osteoblasts are mononucleate. Active osteoblasts are situated on the surface of osteoid seams and communicate with each other via gap-junctions. They contain alkaline phosphatase—a chemical which has a role in the mineralisation of bone.

Bone Lining Cells (BLCs) share a common lineage with osteogenesis (bone forming) cells. They function as a barrier for certain ions, induced osteogenetic cells. They are flattened, mononucleate cells which line bone.

However, osteocytes do originate from osteoblasts which have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by bone matrix which they themselves produce. The space which they occupy is known as a lacuna. Osteocytes have many processes which reach out to meet osteoblasts probably for the purposes of communication. Their functions include to varying degrees: formation of bone, matrix maintenance and calcium homeostasis. They possibly act as mechano-sensory receptors—regulating the bones' response to stress.

If osteoblasts can be described as bone forming cells, the osteoclasts can be described as bone destroying cells. Osteoclasts are large, multinucleated cells located on bone surfaces in what are called Howship's lacunae. These lacunae, or resorption pits, are left behind after the breakdown of bone and often present as scalloped surfaces. Because the osteoclasts are derived from a monocyte stem-cell lineage, they are equipped with engulfment strategies similar to circulating macrophages. Osteoclasts mature and/or migrate to discrete bone surfaces. Upon arrival active enzymes, such as acid phosphatase, are secreted against the mineral substrate. This process, called bone resorption, allows stored calcium to be released into systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations and are known as bone turnover, or remodeling. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts, coupled together via paracrine cell signalling, are referred to as bone remodeling units. The iteration of remodeling events at the cellular level is influential on shaping and sculpting the skeleton both during growth as well as after.

Matrix

The matrix comprises the other major constituent of bone. It has inorganic and organic parts. The inorganic is mainly crystalline mineral salts and calcium, which is present in the form of hydroxyapatite. The matrix is initially laid down as unmineralized osteoid (manufactured by osteoblasts). Mineralisation involves osteoblasts secreting vesicles containing alkaline phosphatase. This cleaves phosphate groups and acts as the foci for calcium and phosphate deposition. The vesicles then rupture and act as a centre for crystals to grow on.

The organic part of matrix is mainly Type I collagen. This is made intracellularly as tropocollagen and then exported. It then associates into fibrils. Also making up the organic part of matrix include various growth factors, the functions of which are not fully known. Other factors present include GAGs, osteocalcin, osteonectin, bone sialo protein and Cell Attachment Factor.

Formation

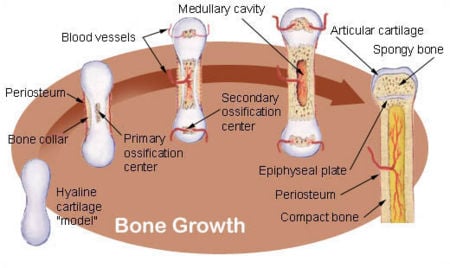

The formation of bone occurs by two methods: intramembranous and endochondral ossification.

- Intramembranous ossification mainly occurs during formation of the flat bones of the skull; the bone is formed from mesenchyme tissue.

- Endochondral ossification occurs in long bones, such as limbs; the bone is formed from cartilage.

Intramembranous ossification

- Development of ossification center

- Calcification

- Formation of trabeculae

- Development of periosteum

Endochondral ossification

- Development of cartilage model

- Growth of cartilage model

- Development of the primary ossification center

- Development of medullary cavity

- Development of the secondary osification center

- Formation of articular cartilage and epiphysial plate

Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called "primary ossification centers." They mostly appear during fetal development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth, and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphyses and the epiphyses of long bones remain separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the metaphysis) until the child reaches skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), whereupon the cartilage ossifies, fusing the two together (epiphyseal closure).

Marrow can be found in almost any bone that holds cancellous tissue. In newborns, all such bones are filled exclusively with red marrow (or hemopoietic marrow), but as the child ages it is mostly replaced by yellow marrow (or fatty marrow). In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the flat bones of the skull, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones.

Remodeling is the process of resorption followed by replacement of bone with little change in shape and occurs throughout a person's life. Its purpose is the release of calcium and the repair of micro-damaged bones (from everyday stress). Repeated stress results in the bone thickening at the points of maximum stress. It has been hypothesized that this is a result of bone's piezoelectric properties, which cause bone to generate small electrical potentials under stress.

Bone pathologies

One of the most common bone illnesses is a bone fracture. Bones heal by natural processes, but untended and unsupported can lead to misgrown bone.

Other illnesses are for example osteoporosis and bone cancer (osteosarcoma). The joints can be affected by arthritis.

Terminology

process A relatively large projection or prominent bump. articulation The region where adjacent bones contact each other—a joint. articular process A projection that contacts an adjacent bone. eminence A relatively small projection or bump. tuberosity A projection or bump with a roughened surface. tubercle A projection or bump with a roughened surface, generally smaller than a tuberosity. trochanter One of two specific tuberosities located on the femur. spine A relatively long, thin projection or bump. suture Articulation between cranial bones. malleolus One of two specific protuberances of bones in the ankle. condyle A large, rounded articular process. epicondyle A projection near to a condyle but not part of the joint. line, ridge A long, thin projection, often with a rough surface. crest A prominent ridge. facet A small, smooth articular surface. foramen An opening through a bone. fossa A broad, shallow depressed area. canal A long, tunnel-like foramen, usually a passage for notable nerves or blood vessels. meatus A short canal. sinus A cavity within a cranial bone.

There are also names for specific parts of long bones.

diaphysis, shaft The long, relatively straight main body of the bone; region of primary ossification. epiphyses The end regions of the bone; regions of secondary ossification. epiphyseal plate The thin sheet of bone marking the fusion of epiphyses to the diaphysis (adults only). head The proximal articular end of the bone. neck The region of bone between the head and the shaft.

See also

- List of bones of the human skeleton

- Terms for anatomical location

There are also names for different side of the bones:

Medial: Side of the bone towards the centre line of the body.

Lateral: Side of bone towards the outside line of the body.

So for example, using your right foot as an example,the left side of your big toe is called the medial side;whilst the right side of your little toe would be on the lateral side.

Also:

Proximal: Towards the top of your skull.

Distal: Towards the bottom of your feet.

Thus, the proximal end of the femur would be the head which joins at the hip, whilst the distal end of the femur would be the end which joins with the tibia.

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.