Difference between revisions of "Bauhaus" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{claimed}} | + | {{claimed}}{{Contracted}} |

[[Image:Bauhaus.JPG|thumb|300px|Restored workshop block of the Dessau Bauhaus (2003).]] | [[Image:Bauhaus.JPG|thumb|300px|Restored workshop block of the Dessau Bauhaus (2003).]] | ||

Revision as of 16:11, 9 April 2007

Bauhaus is the common term for the Staatliches Bauhaus, an art and architecture school in Germany that operated from 1919 to 1933 and briefly in the United States from 1937 to 1938 and for the approach to design that it developed and taught. The most natural meaning for its name (related to the German verb for "build") is Architecture House. Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture.[1]

The Bauhaus art school had (and still has) undoubtedly the biggest influence for modern design in architecture and interior design in modern times.

The Bauhaus art school existed in four different cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932, Berlin from 1932 to 1933) and Chicago from 1937 to 1938, under four different architect-directors (Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 to 1933 and László Moholy-Nagy from 1937 to 1938). The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. When the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, for instance, although it had been an important revenue source, the pottery shop was discontinued. When Mies took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it.

Context

The foundation of the Bauhaus occurred at a time of crisis and turmoil in Europe as a whole and particularly in Germany. Its establishment resulted from a confluence of a diverse set of political, social, educational and artistic shifts in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Politics

The conservative modernization of the German Empire during the 1870s had maintained power in the hands of the aristocracy. It also necessitated militarism and imperialism to maintain stability and economic growth. By 1912 the rise of the leftist SPD had galvanised political positions with notions of international solidarity and socialism set against imperialist nationalism. World War I ensued in 1914.

In 1917 in the midst of the carnage of the First World War, the Bolsheviks, acting in the name of the Russian workers’ and soldiers’ Soviets (Russian for councils) seized power in Russia. Inspired by the Russian workers’ and soldiers’ Soviets, similar German communist factions—most notably the Spartacist League—were formed, seeking a similar revolution for Germany. The following year, the death throes of the war provoked the German Revolution, with the SPD securing the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm and the formation of a revolutionary government. On 1 January 1919, the Spartacist League attempted to take control of Berlin, an action that was brutally suppressed by the combined forces of the SPD, the remnants of the German Army, and paramilitary groups.

Elections were held on the January 19th, and the Weimar Republic was established. Communist revolution remained a goal for many, indeed a Soviet republic was declared in Munich, before it was suppressed. Sporadic fighting continued to flare up around the country.

Art and architecture

Art nouveau (or Jugendstil in Germany) had broken the preoccupation with revivalist historical styles that had characterized the 19th century. In the first decade of the new century however, the movement received criticism; impelled partly by moral yearnings for a sterner and more unadorned style and in part by rationalist ideas requiring practical justification for formal effects. Nonetheless, the movement had opened up a language of abstraction which was to have a profound importance during the 20th century. Adolf Loos was the most effective critic, publishing Ornament and Crime in 1908 which argued that the urge to decorate surfaces was primitive. His work was feted by the later modern movement and acted as a catalyst for the abandonment of surface decoration.

Two further influences upon the emergent architectural thinking of the time can be traced from the 1903 directorships of Hans Poelzig to the Applied Art School in Breslau and Peter Behrens to the Applied Art School in Dusseldorf.

The work of Peter Behrens for the German electrical company AEG attempted to bridge the widening gap between art and mass production. He created clean-lined designs for the company's graphics, industrial design and factories which did not rely on surface decoration, but made full use of newly developed materials such as poured concrete and exposed steel. This work was much admired by the Deutscher Werkbund which had been established in 1907 to forge a closer relationship between German manufacturers and artists.

A number of artists began to develop their own creative languages which relied increasingly on abstraction. These included the fauvists (c. 1905) such as Henri Matisse in France, Cubism developed by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso (c. 1908); der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) movement (1911) of Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc and August Macke in Germany; and the Dutch de Stijl (1917) movement that included Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg.

- 1903 Hans Poelzig - directorship of applied art school in Beslau

- 1903 Peter Behrens - directorship of applied art school in Dussledorf

- 1906 Wilhelm Ernst founds the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar (German:Grossherzogliche Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule) under Henry van de Velde and the Grand-Ducal Saxon Academy of fine arts (German:Grossherzogliche Sächsische Hochschule für Bildende Kunst).

Expressionism

- 1914-1918 Discussions between Saxon state ministry and Fritz Mackensen head of the Grand-Ducal Saxon Academy of fine arts as to the relative importance in the teaching of fine and applied art.

- 1918 Arbeitsrat für Kunst and Bruno Taut and Expressionist architecture

- 1919 Gropius writes the pamphlet for 'Exhibition of unknown architects' -

to go into buildings, endow them with fairy tales....and build in fantasy[sic] without regard for technical difficulty.[2]

- Gropius argued for autonomy of applied arts, with a workshop-based education for both designers and craftsmen.

- Mackenson argues for artist-craftsmen to be educated in a fine art academy.

- 1919 Gropius becomes head of composite institution consisting of the Academy of Art and the School of Arts and Crafts.[1]

Dada

Arbeitrat fur Kunst

Constructivism

Education

- 1890 onwards Gestalt psychology - Über Gestaltqualitäten ("On Gestalt-qualities").

- 1898 Dresdner Werkstätten (Hellerau) becoming Deutsche Werkstätten - Karl Schmidt - reform of applied art education in Germany.

- 1907 Maria Montessori school opens

- Friedrich Wilhelm August Froebel

- Psychoanalysis

- 1893 Philosophy of Freedom

- 1902 German branch of Theosophical Society

- 1919 Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophical society

Society

The Bauhaus aimed to teach the arts and crafts in tandem and to bridge the widening gulf between the art and industry.

- 1907 Deutscher Werkbund

Behrens work for AEG forged new links between art and industry. AEG work admired by the Deutsche Werkbund – a crucial organization for the coming to terms with the age of mechanisation. Improvement of mass housing aim of Werkbund.

Mass production of consumer goods

Mechanisation - Industry

History of the Bauhaus

Weimar

The school was founded by Gropius at the conservative city of Weimar in 1919, as a merger of the Weimar School of Arts and Crafts (Grossherzogliche Kunstgewerbeschule) and the Weimar Academy of Fine Arts (Grossherzogliche Hochschule für Bildende Kunst). His opening manifesto proclaimed:-

to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist.[2]

Most of the contents of the workshops had been sold off during World War I. The early intention was for the Bauhaus to be a combined architecture school, crafts school, and academy of the arts. Much internal and external conflict followed.

Gropius argued that a new period of history had begun with the end of the war. He wanted to create a new architectural style to reflect this new era. His style in architecture and consumer goods was to be functional, cheap, and consistent with mass production. To these ends, Gropius wanted to reunite art and craft to arrive at high-end functional products with artistic pretensions. The Bauhaus issued a magazine called "Bauhaus" and a series of books called "Bauhausbücher". Its head of printing and design was Herbert Bayer.

Many believe that German reform in art education was critical for economic reasons. Since the country lacked the quantity of raw materials that the United States and Great Britain had, they had to rely on the proficiency of its skilled labor force and ability to export innovative and high quality goods. Therefore designers were needed and so was a new type of art education. The school’s philosophy basically stated that the artist should be trained to work with the industry.

Funding for the Bauhaus was initially provided by the Thuringian state parliament. Parliamentary support for the school emanated from the Social Democratic party. In February 1924, the Social Democrats lost control of the state parliament to the nationalists, who were hostile to the Bauhaus's leftist programme. September saw the Ministry of Education place the staff on six-month contracts and cut the school's funding in half. For Gropius, who had already been looking for alternative sources of funding, this proved to be the last straw. Together with the Council of Masters he announced the closure of the Bauhaus from the end of March 1925. The SPD, who had governed in Dessau for years, offered to establish the Bauhaus in the city. Gropius and his staff moved there in 1926.

After the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, a school of industrial design with teachers and staff less antagonistic to the conservative political regime remained in Weimar. This school was eventually known as the Technical University of Architecture and Civil Engineering and in 1996 changed its name to Bauhaus University Weimar.

Dessau

In 1927, the Bauhaus style and its most famous architects heavily influenced the exhibition "Die Wohnung" ("The Dwelling") organized by the Deutscher Werkbund in Stuttgart. A major component of that exhibition was the Weissenhof Siedlung, a settlement or housing project. Gropius was succeeded by Hannes Meyer, and then in turn by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Berlin

Paul Schultze-Naumburg

Under increasing political pressure the Bauhaus was closed on the orders of the Nazi regime on April 11 1933. The Nazi Party and other fascist political groups had opposed the Bauhaus throughout the 1920s. They considered it a front for communists, especially because many Russian artists were involved with it. Consequently, many Weissenhof architects fled to the Soviet Union, thus strengthening the effect. Nazi writers such as Wilhelm Frick and Alfred Rosenberg called the Bauhaus "un-German," and criticized its modernist styles. (See Degenerate art.)

Architectural output

The paradox of the early Bauhaus was that, although its manifesto proclaimed that the ultimate aim of all creative activity was building, the school wouldn't offer classes in architecture until 1927. The single most profitable tangible product of the Bauhaus was its wallpaper.

During the years under Gropius (1919–1927), he and his partner Adolf Meyer observed no real distinction between the output of his architectural office and the school. So the built output of Bauhaus architecture in these years is the output of Gropius: the Sommerfeld house in Berlin, the Otte house in Berlin, the Auerbach house in Jena, and the competition design for the Chicago Tribune Tower, which brought the school much attention. The definitive 1926 Bauhaus building in Dessau is also attributed to Gropius. Student work amounted mainly to unbuilt projects, interior finishes, and craft work like cabinets, chairs and pottery.

In the two years under the outspoken Swiss Communist architect Hannes Meyer, the architectural focus shifted away from aesthetics and towards functionality. But there were major commissions: one by the city of Dessau for five tightly designed "Laubenganghäuser" (apartment buildings with balcony access), which are still in use today, and another for the headquarters of the Federal School of the German Trade Unions (ADGB) in Bernau bei Berlin. Meyer's approach was to research users' needs and scientifically develop the design solution.

And then Mies van der Rohe repudiated Meyer's politics, his supporters, and his architectural approach. As opposed to Gropius' "study of essentials", and Meyer's research into user requirements, Mies advocated a "spatial implementation of intellectual decisions", which effectively meant an adoption of his own aesthetics. Neither Mies nor his Bauhaus students saw any projects built during the 1930s.

The popular conception of the Bauhaus as the source of extensive Weimar-era working housing is not accurate. Two projects, the apartment building project in Dessau and the Törten row housing also in Dessau fall in that category, but it may be fair to say that developing worker housing was not the first priority of Gropius nor Mies. It was the Bauhaus contemporaries Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig and particularly Ernst May, as the city architects of Berlin, Dresden and Frankfurt respectively, who are rightfully credited with the thousands of socially progressive housing units built in Weimar Germany. In Taut's case, the housing may still be seen in SW Berlin, is still occupied, and can be reached by going easily from the Metro Stop Onkel Tom's Hutte.

Impact

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, the United States and Israel in the decades following its demise, as many of the artists involved fled, or were exiled, by the Nazi regime.

Gropius, Breuer, and Moholy-Nagy re-assembled in England during the mid 1930s to live and work in the Isokon project before the war caught up to them. In the late 1930s, Mies van der Rohe re-settled in Chicago and became one of the pre-eminent architects in the world. Moholy-Nagy also went to Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus school under the sponsorship of industrialist and philanthropist Walter Paepcke. Printmaker and painter Werner Drewes was also largely responsible for bringing the Bauhaus aesthetic to America and taught at both Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. Herbert Bayer, sponsored by Paepcke, moved to Aspen, Colorado in support of Paepcke's Aspen projects.

Both Gropius and Breuer went to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and worked together before their professional split in 1941. The Harvard School was enormously influential in the late 1940s and early 1950s, producing such students as Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, Lawrence Halprin and Paul Rudolph, among many others.

One of the main objectives of the Bauhaus was to unify art, craft, and technology. The machine was considered a positive element, and therefore industrial and product design were important components. Vorkurs ("initial course") was taught; this is the modern day Basic Design course that has become one of the key foundational courses offered in architectural schools across the globe. There was no teaching of history in the school because everything was supposed to be designed and created according to first principles rather than by following precedent.

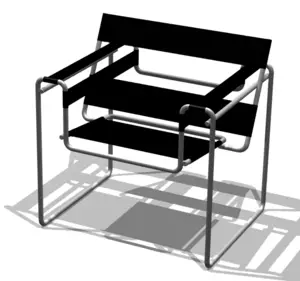

One of the most important contributions of the Bauhaus is in the field of modern furniture design. The world famous and ubiquitous Cantilever chair by Dutch designer Mart Stam, using the tensile properties of steel, and the Wassily Chair designed by Marcel Breuer are two examples.

The physical plant at Dessau survived the War and was operated as a design school with some architectural facilities by the Communist German Democratic Republic. This included live stage productions in the Bauhaus theater under the name of Bauhausbühne ("Bauhaus Stage"). After German reunification, a reorganized school continued in the same building, with no essential continuity with the Bauhaus under Gropius in the early 1920s [2].

In 1999 Bauhaus-Dessau College started to organize postgraduate programs with participants from all over the world. This effort has been supported by the Bauhaus-Dessau Foundation which was founded in 1994 as a public institution.

American art schools have also rediscovered the Bauhaus school. The Master Craftsman Program at Florida State University bases its artistic philosophy on Bauhaus theory and practice.

Many outstanding artists of their time were lecturers at Bauhaus:

|

|

Gallery

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [2006] A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback), Second (in English), Oxford University Press, 880. ISBN 0198606788.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kenneth Frampton. Modern Architecture: A Critical History (World of Art), 3rd ed. Thames & Hudson, 1992. ISBN 0500202575, p. 123.

- Oskar Schlemmer. Tut Schlemmer, Editor. The Letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer. Translated by Krishna Winston. Wesleyan University Press, 1972. ISBN 0819540471

- Magdalena Droste, Peter Gossel, Editors. Bauhaus, Taschen America LLC, 2005. ISBN 3822836494

- Marty Bax. Bauhaus Lecture Notes 1930-1933. Theory and practice of architectural training at the Bauhaus, based on the lecture notes made by the Dutch ex-Bauhaus student and architect J.J. van der Linden of the Mies van der Rohe curriculum. Amsterdam, Architectura & Natura 1991. ISBN 9071570045

External links

- Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin

- Foundation bauhaus dessau

- Review of Hotel Brandenburger Hof Berlin with Bauhaus design furniture

- Bauhaus School

- Bauhaus in America. A documentary describing the impact on Bauhaus on American architecture.

- Bauhaus in Budapest

- Student Short Film on late Bauhaus (2006)

| Western art movements |

| Renaissance · Mannerism · Baroque · Rococo · Neoclassicism · Romanticism · Realism · Pre-Raphaelite · Academic · Impressionism · Post-Impressionism |

| 20th century |

| Modernism · Cubism · Expressionism · Abstract expressionism · Abstract · Neue Künstlervereinigung München · Der Blaue Reiter · Die Brücke · Dada · Fauvism · Art Nouveau · Bauhaus · De Stijl · Art Deco · Pop art · Futurism · Suprematism · Surrealism · Minimalism · Post-Modernism · Conceptual art |

| |||||||

....

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.