Bandiagara Escarpment

| Cliff of Bandiagara (Land of the Dogons)* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | v, vii |

| Reference | 516 |

| Region** | Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1989 (13th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

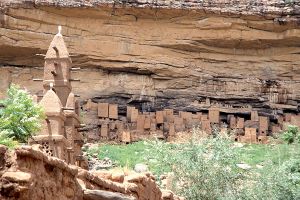

The Bandiagara Escarpment is a sandstone cliff in the Dogon country of Mali that rises almost 1,640 feet (500 m) above the lower sandy flats to the south. It is approximately 100 miles (150 km) long. The Tellem people inhabited the escarpment until the fifteenth century, and many structures remain from the Tellem period. The area is inhabited today by the Dogon people. The Dogon have a strong sense of ethnic identity that enabled them to largely resist Islamization, colonialization, and the slave trade. The cliffs aided the Tellem by providing sanctuary into which they were able to retreat and conceal themselves.

In 1989 UNESCO listed the Bandiagara Escarpment as a World Heritage Site, noting it as "an outstanding landscape of cliffs and sandy plateaux with some beautiful architecture." The Bandiagara site is considered one of West Africa's most impressive features, due to its geological and archaeological features as well as its ethnological importance.

The Cliffs of Bandiagara

The Cliffs of Bandiagara are a sandstone chain ranging from south to northeast over 150 km and extending to the Grandamia massif. The end of the massif is marked by the Hombori Tondo, Mali's highest peak at 3,783 feet (1,115 m). Because of its archaeological, ethnological, and geological characteristics, the entire site is one of the most imposing in West Africa. Three sculptures that the Dogon attribute to the Tellem have been dated by carbon-14 to the fifteen to seventeenth centuries C.E. These figures, usually of simplified and elongated form, often with hands raised, seem to be the prototype of the ancestor figures that the Dogon carve on the doors and locks of their houses.

Dozens of villages are located along the cliff, such as Kani Bonzon. It was near this village that the Dogons arrived in the fourteenth century, and from there they spread over the plateau, the escarpment, and the plains of the Seno-Gondo to the southeast.

Tellem

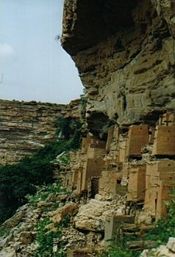

The cave-dwelling Tellem, an ethnic group apparently pushed out by the arrival of the Dogons, once lived on the slopes of the cliff. The Tellem legacy is evident in the caves they carved into the cliffs to bury their dead high up, far from the frequent flash floods of the area. The Tellem were pygmies or "small red people" who built dwellings around the base of the escarpment as well as directly into the cliff-face. Many of these structures are still visible in the area.

In the Bandiagara cliffs, carved wooden headrests have been found in burial caves. The Dogon, who do not now use headrests, attribute them to the Tellem, who inhabited the region from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries. Rogier Bedaux, who has excavated in the burial caves, asserts that headrests "do not occur in Dogon contexts." Tellem headrests that have been excavated from documented cave sites have elegant silhouettes but minimal decoration. Some headrests have animal heads projecting from either end of the curved upper platform. The headrests may either have been burial gifts or the items used by the deceased during their lifetime. The burial caves also contained other objects: bowls, pottery, necklaces, bracelets, rings, and iron staffs. Headrests may have been objects of high status, because only a few caves contained them.

The Tellem people have disappeared from the area either by assimilation into the Dogon culture or some other unknown reason. It is thought by some in Mali today that the Tellem possessed the power of flight. A common understanding is that under pressure from the Dogon, the Tellem may have migrated to nearby Burkina Faso. Their tiny structures can still be seen, perched in higher parts of the cliffs.

Dogon history

Historically, Dogon villages frequently became victims of Islamic slave raiders.[1] Neighboring Islamic tribal groups acted as slave merchants,[2] as the growth of cities increased the demand for slaves across the region of West Africa. The historical pattern included murder of males by Islamic jihadists and enslavement of women and children.[1] As early as the twelfth century the Dogon people had fled west to avoid both conversion to Islam and enslavement.[1]

Relics of the Dogon are found in Burkina Faso's north and northwest regions. The Dogon left the area around the fifteenth century to settle in the cliffs of Bandiagara. After sharing the escarpment with the Tellem, the Tellem were pushed out.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the jihads that were triggered by the resurgence of Islam caused slaves to be sought for warfare. Dogon insecurity in the face of these historical pressures caused them to locate their villages in defensible positions along the walls of the escarpment. The other factor influencing their choice of settlement location is water. The Niger River is nearby, and a rivulet runs at the foot of the cliff at the lowest point of the area during the wet season.

Some Tellem buildings-most notably the granaries-are still used by the Dogon, although generally Dogon villages are at the bottom or top of the escarpment, where water gathers and farming is possible. During the years when slave traders were raiding villages, the Dogon retreated to the cliffs for security.[3]

The Dogon went relatively undisturbed by the French colonial powers. Supposedly there are a series of natural tunnels weaving through the Bandiagara Escarpment that only the Dogon know about and which they use to surprise and drive away any aggressors.

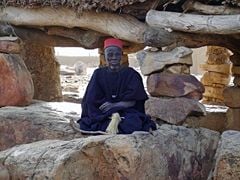

Dogon today

The area known as Dogon Country is in eastern Mali near the Burkina Faso border. Throughout the colonial era, their isolation enabled the Dogon to retain their culture and animist beliefs, despite the growing strength of Islam and Christianity around them. The Dogon are best known for their mythology, their mask dances, wooden sculpture, and architecture. The past century has seen significant changes in their social organization, material culture, and beliefs, partly because Dogon Country is one of Mali's major tourist attractions.

The current population is at least 450,000. The hardworking Dogon raise sweet onions and other crops through irrigation on tiny patches of land.

Dogon art

Dogon art is primarily sculpture and revolves around religious values, ideals, and freedoms. The sculptures are not intended for public view and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or kept with the Hogon (spiritual leader). The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made.

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture consist of figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, aproned figures, and standing figures. Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art. Influences from Tellem art are evident in Dogon art because of its rectilinear designs.

Dogon culture and religion

The majority of Dogon practice an animist religion, including the ancestral spirit Nommo, with its festivals and mythology. A significant minority of the Dogon practice Islam, and some have been converted by missionaries to Christianity.

Each Dogon community, or enlarged family, is headed by one male elder. This chief head is the oldest living son of the ancestor of the local branch of the family. According to the NECEP database, within this patrilineal system of polygynous marriages, up to four wives can be taken.

Most men, however, have only one wife, and it is rare for a man to have more than two wives. Formally, wives only join their husband's household after the birth of their first child. Women may leave their husbands early in their marriage, before the birth of their first child. After having children, divorce is a rare and serious matter, and it requires the participation of the whole village. An enlarged family can count up to one hundred persons and is called a guinna.

The Dogon are strongly oriented toward harmony, which is reflected in many of their rituals. For instance, in one of their most important rituals, the women praise the men, the men thank the women, the young express appreciation for the old, and the old recognize the contributions of the young. Another example is the custom of elaborate greetings whenever one Dogon meets another. This custom is repeated over and over, throughout a Dogon village, all day. During a greeting ritual, the person who has entered the contact answers a series of questions about his or her whole family, from the person who was already there. Invariably, the answer is sewa, which means that everything is fine. Then the Dogon who has entered the contact repeats the ritual, asking the resident how his or her whole family is. Because of the word sewa is so commonly repeated throughout a Dogon village, neighboring peoples have dubbed the Dogon the sewa people.

The Hogon is the spiritual leader of the village. He is elected from among the oldest men of the enlarged families of the village.

The Dogon maintain an agricultural mode of subsistence, and cultivate pearl millet, sorghum, and rice, as well as onions, tobacco, peanuts, and some other vegetables. Their onions are sold as far as the market of Bamako and even Ivory Coast. They also raise sheep, goats, and chickens. Grain is stored in granaries.

Looking ahead

Today Mali is among the poorest countries in the world, with 65 percent of its land area desert or semi-desert. About ten percent of the population is nomadic and some 80 percent of the labor force is engaged in farming and fishing. Mali is heavily dependent on foreign aid and vulnerable to fluctuations in world prices for cotton, its main export, along with gold.[4] The Dogon of the Bandiagara exist on subsistence agriculture, as does most of the country's population. As one of West Africa's most impressive features, the Bandiagara Escarpment attracts tourists to the country. The cliffs and caves of the Bandiagara Escarpment have provided home and shelter to some of Mali's ethnic groups for nearly seven centuries. They could conceivably be used in the same manner for centuries longer. However, with the progression of time and as changes occur in the natural environment, even those in the world's farthest reaches will be affected. The Dogon are strongly oriented toward harmony, which is reflected in many of their rituals. This attribute can be expected to aid them as relationships outside their society increase.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Christopher Wise, Yambo Ouologuem: Postcolonial Writer, Islamic Militant (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999).

- ↑ Timothy Insoll, The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- ↑ John Reader, Africa: A Biography of the Continent (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998, ISBN 0679409793), 409.

- ↑ Library of Congress (January 2005), Country Profile: Mali Retrieved February 7, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beaudoin, Gerard. 1997. Les Dogon du Mali Ed. BDT Développement. ISBN 295110300X

- Bedaux, R. and J.D. van der Waals (eds.). 2003. Dogon: mythe en werkelijkheid in Mali [Dogon: myth and reality in Mali]. Leiden: National Museum of Ethnology.

- Davis, Shawn R. “Dogon Funerals” in African Art; Summer 2002, Vol. 35 Issue 2.

- Dolo, Sékou Ogobara. La mère des masques. Un Dogon raconte. 2002. Eds. Seuil ISBN 2020411334 Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- Griaule, Marcel. 1965. Conversations With Ogotemmeli: An Introduction to Dogon Religious Ideas, 1st. ed. ISBN 0195198212

- Laude, Jean. 1973. African Art of the Dogon: The Myths of the Cliff Dwellers. New York: Viking Press.

- Morton, Robert (ed.). Stephenie Hollyman (photographs), and Walter E.A. van Beek (text). 2001. Dogon: Africa's people of the cliffs. New York: Abrams. ISBN 0810943735

- Reader, John. 1998. Africa: A Biography of the Continent. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0679409793

- Wanono, Nadine, and Michel Renaudeau. 1996. Les Dogon. Paris: Éditions du Chêne-Hachette. ISBN 2851089374

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Cliff of Bandiagara (Land of the Dogons) Retrieved February 6, 2009.

External links

All links retrieved May 11, 2016.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.