Difference between revisions of "Asgard" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m |

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Started}}{{Contracted}} |

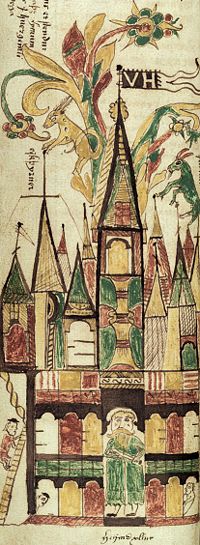

| − | [[Image:AM 738 4to Valhöll.jpg|right|thumb|200px|In this illustration from a | + | [[Image:AM 738 4to Valhöll.jpg|right|thumb|200px|In this illustration from a 17th century [[Iceland]]ic manuscript, [[Heimdall]] is shown guarding the gate of [[Valhalla]]. This divine hall is thought to be one of the many contained within the walls of Asgard.]] |

| − | In | + | In [[Norse mythology]], '''Asgard''' (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'') was the realm of the Gods (the [[Aesir]]) that was mythologically connected to the abode of mortals ([[Midgard]]) via the rainbow bridge. Though Asgard was understood as the home of the Norse Gods, it should not be conflated with the Judeo-Christian notion of [[Heaven]]. Instead, it, like the Greek [[Mount Olympus]], was seen as the residence of the gods and the locus for many tales of the gods and their doings. As such, Asgard included various dwelling places and feasting halls of the gods (including [[Valhalla]], [[Odin]]'s heavenly hall where honorable warriors were sent). |

| − | While Asgard was | + | While it is said that Asgard was destroyed at [[Ragnarök]], the second-generation deities that survived the apocalypse were propheized to rebuild it, ushering in an new era of prosperity. Other religions, too, speak of cosmic renewal and restoration after a long process of divine providence. |

==Asgard in a Norse Context== | ==Asgard in a Norse Context== | ||

| − | As an important | + | As an important tale in Norse mythology, Asgard belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the [[Scandinavia|Scandinavian]] and [[Germany|Germanic]] peoples. This mythological tradition developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..<ref>Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).</ref> |

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the ''Aesir'', the ''Vanir'', and the ''Jotun''. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.<ref>More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.</ref> The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. | Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the ''Aesir'', the ''Vanir'', and the ''Jotun''. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.<ref>More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.</ref> The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. | ||

Revision as of 05:58, 24 May 2007

In Norse mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: Ásgarðr) was the realm of the Gods (the Aesir) that was mythologically connected to the abode of mortals (Midgard) via the rainbow bridge. Though Asgard was understood as the home of the Norse Gods, it should not be conflated with the Judeo-Christian notion of Heaven. Instead, it, like the Greek Mount Olympus, was seen as the residence of the gods and the locus for many tales of the gods and their doings. As such, Asgard included various dwelling places and feasting halls of the gods (including Valhalla, Odin's heavenly hall where honorable warriors were sent).

While it is said that Asgard was destroyed at Ragnarök, the second-generation deities that survived the apocalypse were propheized to rebuild it, ushering in an new era of prosperity. Other religions, too, speak of cosmic renewal and restoration after a long process of divine providence.

Asgard in a Norse Context

As an important tale in Norse mythology, Asgard belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1]

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Further, their cosmological system postulated a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods (Asgard and Vanaheim, homes of the Aesir and Vanir, respectively), the realm of mortals (Midgard) and the frigid underworld (Niflheim), the realm of the dead. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots.

Though Asgard was understood as the realm of the gods, it should not be conflated with the Judeo-Christian notion of Heaven. Instead, it, like the Grecian Mount Olympus, was the home of the Aesir and, resultantly, was the locus for many tales of the gods and their doings.

Mythic Description(s)

- See also: Valhalla, Yggdrasill, Midgard, Niflheim, Hel

In the mythic corpus, Asgard plays a central (if not always well-articulated) role in the exploits of the Aesir. More specifically, as the primary heavenly realm in the Norse cosmological scheme, it was understood as the place where the gods dwelt, interacted with each other, and surveyed their human constituents.

Descriptions of the various dwelling-places of the Aesir, homes that were always conceptualized as being analogous to the castles and feasting halls of human royalty,[3] were fairly common in mythic texts (and, one can assume, in the skaldic poems that they were based upon). One such source in particular, "Grimnismol" (from the Poetic Edda) is largely concerned with enumerating these citadels and exploring their particular characteristics:

- The land is holy | that lies hard by

- The gods and the elves together;

- And Thor shall ever | in Thruthheim ["the Place of Might"] dwell,

- Till the gods to destruction go.

- ...

- The seventh is Breithablik ["Wide-Shining"]; | Baldr has there

- For himself a dwelling set,

- In the land I know | that lies so fair,

- And from evil fate is free.

- Himinbjorg ["Heaven's Cliffs"] is the eighth, | and Heimdall there

- O'er men holds sway, it is said;

- In his well-built house | does the warder of heaven

- The good mead gladly drink.[4]

The lengthy descriptions from "Grimnismol" are summarized (and in some cases expanded upon) by Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda:

- there is also in that place [Asgard] the abode called Breidablik, and there is not in heaven a fairer dwelling. There, too, is the one called Glitnir, whose walls, and all its posts and pillars, are of red gold, but its roof of silver. There is also the abode called Himinbjörg; it stands at heaven's end by the bridge-head, in the place where Bifröst joins heaven. Another great abode is there, which is named Valaskjálf; Odin possesses that dwelling; the gods made it and thatched it with sheer silver, and in this hall is the Hlidskjálf, the high-seat so called. Whenever Allfather sits in that seat, he surveys all lands.[5]

Further, the divine city was also home to the paradise of Valhalla:

- In Ásgard, before the doors of Valhall, there stands a grove which is called Glasir, and its leafage is all red gold, even as is sung here:

- Glasir stands

- With golden leafage

- Before the High God's halls.[6]

In addition to their role in paraphrasing sections of the Poetic Edda, these selections are also notable for introducing the ideas that the gods themselves constructed Asgard and that Odin's majestic throne allowed him to survey the entirety of the cosmos, both of which will be considered in more detail below.

In addition to the various abodes of the deities, Asgard also featured numerous other mythically important geographical elements. The city of the gods was set upon (or was adjacent to)[7] the splendid plains of Idavoll, a bounteous field where the Aesir would meet to discuss important issues. It was also the location of Yggdrasill's third, world-anchoring root, under which was located the Well of Urd. This well, which was cared for by the Norns, was understood to fulfill two functions: it nourished the World-Tree and was somehow related to destiny or to prophetic wisdom.[8]

The heavenly realm was thought to be connected to the earth (Midgard) via a rainbow bridge (Bifröst, "shimmering path"[9]), which was also constructed by the gods:

- Has it not been told thee, that the gods made a bridge from earth, to heaven, called Bifröst? Thou must have seen it; it may be that ye call it rainbow.' It is of three colors, and very strong, and made with cunning and with more magic art than other works of craftsmanship.[10]

While the description above focuses upon the might of the gods in constructing such a magical conveyance, the reality of Bifröst also highlighted another element of existence in Asgard — namely, the fear of hostile invasion.

Describing the red band in the rainbow, the Prose Edda suggests that "that which thou seest to be red in the bow is burning fire; the Hill-Giants might go up to heaven, if passage on Bifröst were open to all those who would cross."[11] This the constant threat of invasion by the hostile giants (Jotun) represented a genuine fear for the Aesir. In the "Thrymskvitha," an entertaining Eddic poem describing the theft of Thor's hammer, Loki convinces the warrior god that he must dress as a woman to gain admission to a giant's banquet (with the eventual aim of stealing the hammer back). When Thor demurs, Loki chastises him, saying:

- "Be silent, Thor, | and speak not thus;

- Else will the giants | in Asgarth dwell

- If thy hammer is brought not | home to thee."[12] (convincing Thor to cross-dress)

The concern about the possibility of invasion also motivated the Aesir to construct an enormous wall around Asgard, a building project that provides the background for one of the most remarkable mythic accounts concerning this realm (discussed below).

The Term "Asgard"

Though the general understanding that the gods dwelt apart from humans in a discrete, heavenly realm was in common currency among the skalds and mythographers of Norse society, the term is relatively underutilized in the Poetic Edda.[13] Regardless, its centrality in the Prose Edda, plus the fact that its use is attested to in the tenth century poetry,[14] indicates the general cultural currency of the notion. Further, the localization of Fólkvang (Freyja's hall) and Nóatún (Njord's hall) in Asgard[15] instead of Vanaheim would imply that this term, at least to some extant, was a general noun that could be used to describe the dwelling place of the gods (i.e. it was not exclusive to the Aesir).

Specific Mythic Accounts

Construction of Asgard

In the mythic texts, the Aesir are thought to have constructed Asgard at some point in the mythic past. As Snorri suggests,

- In the beginning [Odin] established rulers, and bade them ordain fates with him, and give counsel concerning the planning of the town; that was in the place which is called Ida-field, in the midst of the town. It was their first work to make that court in which their twelve seats stand, and another, the high-seat which Allfather himself has. That house is the best-made of any on earth, and the greatest; without and within, it is all like one piece of gold; men call it Gladsheim.[16]

However, once these various homes and meeting halls were completed, the Aesir realized that they were relatively susceptible to attack. Fortuitously (or so it seemed at the time), a giant stopped by and offered to construct them an impregnable wall and a gate to protect their fledgling realm. However, his terms were quite steep, as he wished to receive in payment the hand of Freya in marriage, as well as the sun and the moon. The Aesir agreed to this bargain, on the condition that the work be completed within six months, and that he do it with no help (as they assumed that such a task would simply be impossible to complete). The giant stone-wright agreed to this once Loki convinced the Æsir to allow him to use his stallion to help in the building process.

As the end of summer neared and construction was proceeding apace, the gods regretted their contract and the solemn vows with which they had concluded it. Since the giant's horse had proved to be an invaluable asset to his progress, they threatened Loki with horrid punishment if he did not somehow disrupt the builder's efforts. Fearful of this, Loki transformed himself into a beautiful mare and pranced past the builder's stallion, who, entranced with bestial lust, proceeded to ignore the building project entirely in order to pursue her.[17] After chasing his horse all night, the builder could see that the job could not be completed on time and fell into a rage:

- When the wright saw that the work could not be brought to an end, he fell into giant's fury. Now that the Æsir saw surely that the hill-giant was come thither, they did not regard their oaths reverently, but called on Thor, who came as quickly. And straightway the hammer Mjöllnir was raised aloft; he paid the wright's wage, and not with the sun and the moon. Nay, he even denied him dwelling in Jötunheim, and struck but the one first blow, so that his skull was burst into small crumbs, and sent him down bellow under Niflhel.[18]

Christian Influences

Euhemeristic Accounts

Intriguingly, some of Snorri Sturluson's depictions of Asgard cast it as a human realm, ruled by a venerable (yet entirely human) clan. While such an approach can doubtlessly be attributed to the increasingly-Christian context that his writings were produced for, it is still a highly intriguing process. In the Prose Edda (in a rather peculiar contrast to the other passages that definitively describe it as a heavenly realm), he identifies the city of the gods with the Troy of Greek mythology:

- Next they made for themselves in the middle of the world a city which is called Ásgard; men call it Troy. There dwelt the gods and their kindred; and many tidings and tales of it have come to pass both on earth and aloft.[19]

In a contrasting (or perhaps complimentary) account, he locates Asgard somewhere in Asia:

- The country east of the Tanaquisl in Asia was called Asaland, or Asaheim, and the chief city in that land was called Asgaard. In that city was a chief called Odin, and it was a great place for sacrifice.[20]

Given that the river Tanaquisl was understood to flow into the Black Sea, it is possible that these two accounts are, in fact, complimentary (especially given the historical difficulties in locating the classical Troy).

Other Evidence

Some depictions of both the gods and the heavens seem to display a similarly syncretic bent. One of the halls of Asgard (Gimlé, "fire-proof") is described in terms that are strongly reminiscent of the Christian notion of Heaven:

- At the southern end of heaven is that hall which is fairest of all, and brighter than the sun; it is called Gimlé. It shall stand when both heaven and earth have departed; and good men and of righteous conversation shall dwell therein.[21]

Likewise, the depiction of Odin's throne at Hlidskjálf transform the All-Father into an omniscient god (which seems to contradict some earlier mythic accounts (including the sacrifice of his eye at Mimir's well and the necessity of his ravens (Hugin and Munin) in patrolling the world and delivering reports to him)): "There is one abode called Hlidskjálf, and when Allfather sat in the high-seat there, he looked out over the whole world and saw every man's acts, and knew all things which he saw."[22]

Ragnarök

As with many other elements of the mythic cosmos, Asgard was fated to be destroyed in the world-shattering apocalypse of Ragnarök.

First, the myths describe the inevitability of Bifröst being rent asunder by the fire-giants of Muspelheim, who proceed over it in their quest to sack the capital of the gods:

- But strong as [the rainbow bridge] is, yet must it be broken, when the sons of Múspell shall go forth harrying and ride it, and swim their horses over great rivers; thus they shall proceed. ... [N]othing in this world is of such nature that it may be relied on when the sons of Múspell go a-harrying.[23]

After this dreadful assault, the gods and the giants meet upon the battlefield, where most of them are lost in mutually destructive combat. In the aftermath of this conflict, Surtr, the lord of Muspelheim razes the entirety of creation with fire (losing his own life in the process):

- Surt fares from the south | with the scourge of branches,

- The sun of the battle-gods | shone from his sword;

- The crags are sundered, | the giant-women sink,

- The dead throng Hel-way, | and heaven is cloven.

- ...

- The sun turns black, | earth sinks in the sea,

- The hot stars down | from heaven are whirled;

- Fierce grows the steam | and the life-feeding flame,

- Till fire leaps high | about heaven itself.[24]

However, this conflagration does not equate to the ultimate terminus point of history. Indeed, some of the second generation Aesir will survive and will begin to rebuild upon the fields of Ida (amongst the wreckage of their former capital): "Vídarr and Váli shall be living, inasmuch as neither sea nor the fire of Surtr shall have harmed them; and they shall dwell at Ida-Plain, where Ásgard was before."[25]

Other spellings

- Alternatives Anglicisations: Ásgard, Ásegard, Ásgardr, Asgardr, Ásgarthr, Ásgarth, Asgarth, Esageard, Ásgardhr

- Common Swedish and Danish form: Asgård

- Norwegian: Åsgard (also Åsgård, Asgaard, Aasgaard)

- Icelandic, Faroese: Ásgarður

External links

- The Prose Edda, translated by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur, at sacred-texts.com - retrieved May 22, 2007

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Describing the lives of the Icelandic chieftains, Dubois notes that: "his world exactly mirrored that of the divine Asgard, where the gods lived in their own society and held divine councils and feasts" (66).

- ↑ "Grimnismol" (4, 12-13), in the Poetic Edda, 88, 90.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XVII, Brodeur 31.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skalskaparmal XXXIV, Brodeur 145.

- ↑ Sources differ on the precise location of the plain. Orchard, 217.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XV: "The third root of the Ash stands in heaven; and under that root is the well which is very holy, that is called the Well of Urdr; there the gods hold their tribunal" (Brodeur, 27-28). See also: Lindow, 301.

- ↑ Orchard, 60

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XIII, Brodeur 24-25.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XV, Brodeur 28.

- ↑ "Thrymskvitha" (17) in the Poetic Edda, 178-179.

- ↑ In fact, the only two usages are found un the Thrymskvida and the Hymiskvida (Orchard, 35).

- ↑ As summarized by Lindow, one tenth-century skaldic lay to the Thunder God states that "Thor has defended Asgard and Ygg's [Odin's] people [the gods]with strength" (61).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XXIV, Brodeur 38.

- ↑ Gylfaginning XIV, Brodeur 25.

- ↑ As an aside, the stallion does eventually have intercourse with Loki, who then proceeds to give birth to Sleipnir (the eight-legged horse that was given to the All-Father as a gift and that eventually became emblematic of him).

- ↑ Gylfaginning XLII, Brodeur 55.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning IX, Brodeur 21-22.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Ynglinga Saga 2, accessed online at Online Medieval and Classics Library (May 22, 2007).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XVII, Brodeur 31; Orchard, 134.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning IX, Brodeur 22. See also: M Görman, "Old Scandinavian and Christian eschatology," Old Norse and Finnish religions and cultic place-names, edited by Tore Ahlbäck, Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 13, (Åbo, Finland: Donner Institute for Research in Religion & Cultural History, 1990).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XIII, Brodeur 24-25.

- ↑ "Völuspá" (52, 57) in the Poetic Edda, 22, 24.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning LIII, Brodeur 73.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harper and Row, 1961. Translated by Willard R. Trask. ISBN 015679201X.

- Grammaticus, Saxo. The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.